WSC 2023-2024, Conference 18, Case 4

Signalment:

Immature (presumed yearling) female white-tailed deer (Odocolieus virginianus)

History:

In the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, Department of Natural Resources officers were called by a concerned citizen because a young deer was acting strangely in a residential area. The deer would walk in tight circles, had a prominent head tilt, lacked fear of people and appeared to be blind as it would walk into obstacles, fall down, and struggle back to its feet. The deer appeared to be breathing heavily and was drooling excessively. The officer euthanized the deer by shooting her in the head several times with a 22 caliber gun. The head, lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and kidneys were harvested, frozen, and submitted to the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative, Atlantic Region, for examination.

Gross Pathology:

Abundant fat stores were noted in the epicardial groove, in the connective tissue surrounding the kidneys, and within the mesentery indicating that this animal appeared to be in good body condition. There were several skin abrasions on the head (attributed to trauma associated with falling) and traumatic lesions due to mode of euthanasia (i.e., gunshot to the head) were noted.

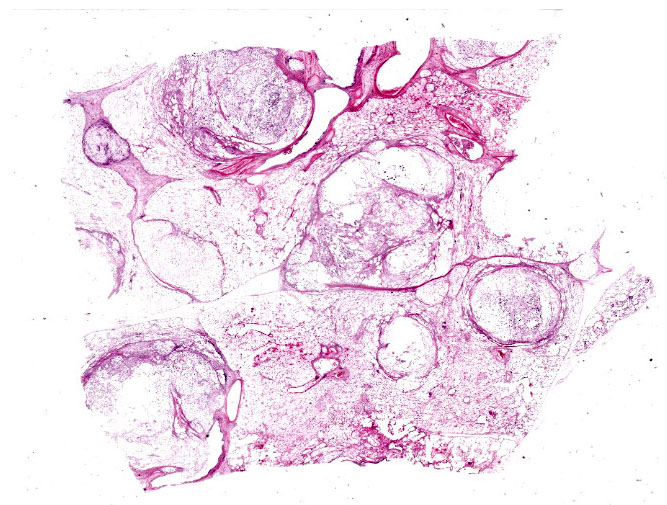

An approximately 4.5 cm x 3.5 cm x 3.5 cm, round, expansile, pale tan mass focally replaced the parenchyma in the left cranioventral lung. This mass was soft and when sectioned, was white-tan with fine fibrous septa dissecting through it. Multiple similar, smaller masses, ranging from 0.5 cm - 1.0 cm in greatest diameter, were randomly scattered throu-ghout the remaining left lung. The right lung was enlarged and largely effaced by multifocal to coalescing similar soft masses, the largest of which measured approximately 8 cm in greatest diameter. The tracheobronchial lymph nodes were moderately to severely enlarged; the largest was approximately 10 cm in greatest diameter and had a necrotic center filled with viscous yellow material. When sectioned, these lymph nodes were otherwise similar in appearance to the grossly affected lung.

Prominent cerebellar coning was noted when the calvarium was removed. When the brain was sectioned sagitally along the midline, several, small, 1-2 mm in greatest diameter, pitted lesions with dark rims were noted in the neuropil of the thalamus and superior colliculus. Following fixation, similar tiny lesions were also noted in the caudal nasal cavity. This exudate largely replaced the right ethmoturbinates and disrupted the adjacent cribiform plate. The inner and middle ears were grossly unremarkable. No significant abnormalities were noted in the liver, kidney, or gastrointestinal tract.

Laboratory Results:

Light growth of Cryptococcus sp. was identified from lymph node culture swabs.

Multilocus sequence typing identified this fungus as Cryptococcus gattii (type VGII).

Microscopic Description:

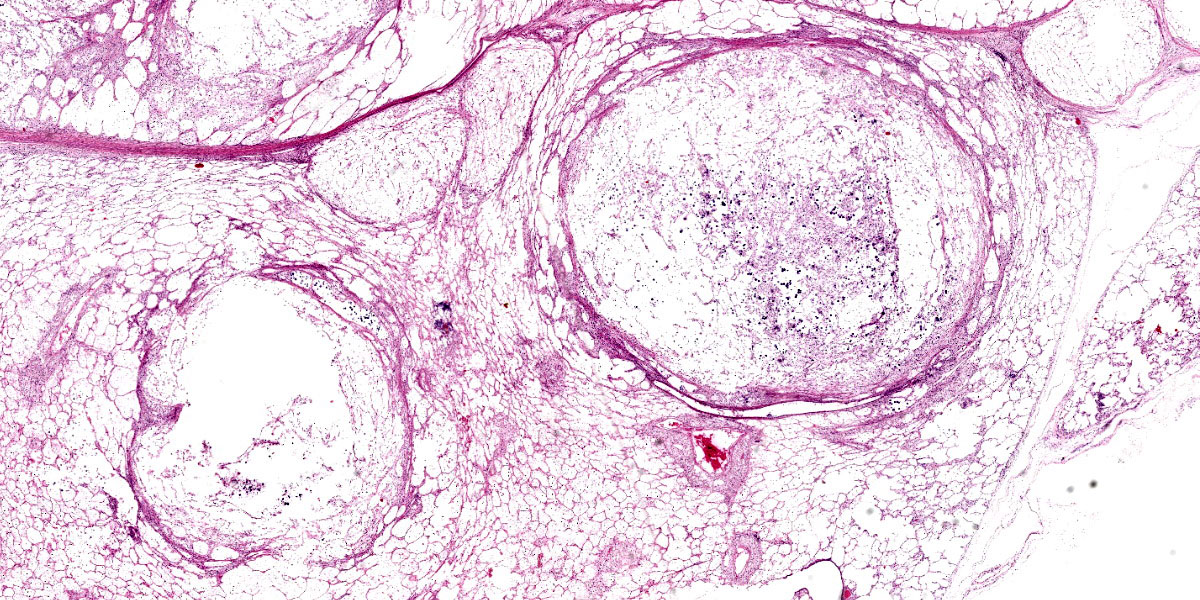

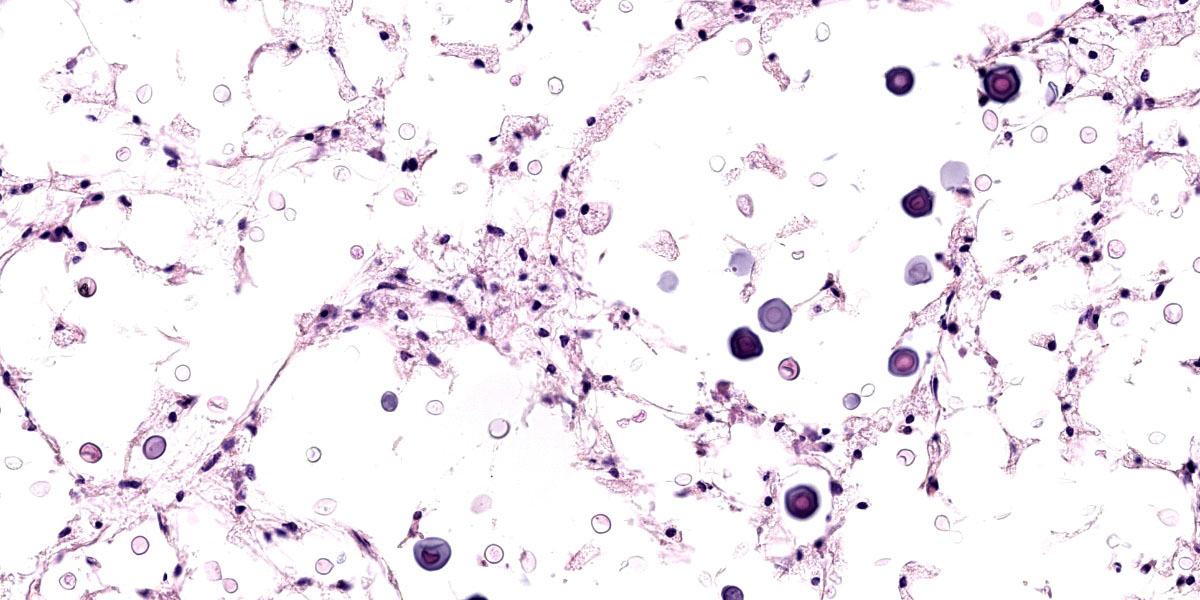

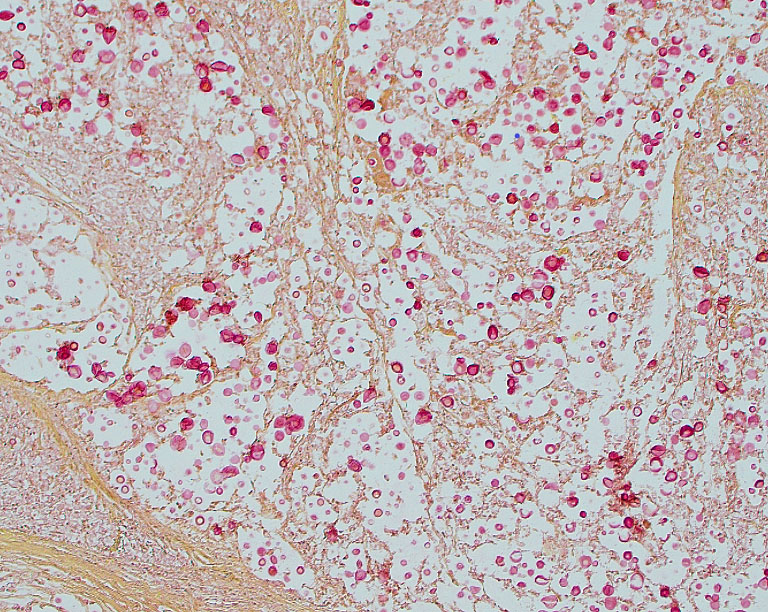

Tissues exhibit moderate autolysis. Sections of the mass-like lesions in the lung are all similar. These masses are poorly defined and are composed of areas where alveoli are markedly expanded and are often ruptured forming variably sized spaces filled with myriads of yeast. Small to moderate infiltrates of large, pale macrophages are also present within these air spaces and the interstitium. A mild increase in fine fibrous stroma multifocally expands the interstitium forming thin septa and sometimes thicker fibrous bands. Yeast are round to ovoid, 10-20 microns in diameter, and have a very pale pink, often faintly visible, thick capsule that is highlighted with mucicarmine staining. In some areas, the capsule appears basophilic. Rarely, very narrow based budding is noted. Many scattered yeasts contain coarse black melanin pigment which is highlighted with Fontana-Masson staining. Large bronchioles are sometimes partially distended with basophilic debris. Occasional dense clusters of bacilli are scattered within the tissue (interpreted as postmortem bacterial overgrowth).

Sections of the ethmoturbinates, brain, and tracheobronchial lymph nodes contain similar lesions, which often appear cystic, and consist of myriads of the described yeast associated with mild to moderate granulomatous inflammation.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, granulomatous, multifocal, mild to moderate, chronic, with myriads of intralesional yeast (compatible with Cryptococcus sp.).

Contributor’s Comment:

The neurologic and respiratory clinical signs reported in this young deer are attributed to severe, systemic infection due to Cryptococcus sp. Multilocus sequence typing identified this fungus as Cryptococcus gattii type VGII. To our knowledge, this is the first laboratory confirmed case of C. gattii infection in the Atlantic provinces in eastern Canada, and the first confirmed case in a deer.

Disease in humans and susceptible animals due to cryptococcosis is generally restricted to several species, grouped into the C. neoformans-C. gattii complex, which include C. neoformans var. neoformans, C. neoformans var. grubii and C. gattii.1,2 C. gattii is further classified via genotyping into 4 groups: VGI, VGII, VGIII, and VGIV.

Until the 1990’s, C. gattii was generally considered restricted to several tropical and subtropical regions of the world, including Australia, South America, southeast Asia, parts of Africa, and an area of California. Since 1999, human hospitals on Vancouver Island, Canada, have reported a marked increase in laboratory confirmed cases of C. gattii (mainly types VGI and VGII) infection and the Pacific Northwest is now considered an endemic area.1 In this same time period, laboratory confirmed cases of C. gattii infections (again, mainly type VGI and VGII) in pet dogs and cats from the area were also common.5 In general, veterinary cases were diagnosed 2-3 times more frequently than human cases.5

C. gattii is considered an emerging pathogen in a broad range of animals and infection has been reported in domestic cats, dogs, horses, sheep, cattle, koalas, dolphins, gray squirrels, ferrets, birds, and marsupials.1 The organism lives in the environment and can be isolated from the soil, bark from a wide variety of trees, and decaying organic material. In endemic areas, the fungus has also been isolated from the air, freshwater, and sea water, and has been recovered from car wheel wells and on footwear from high traffic areas.2 Because of some of the latter findings, disruptive environmental activities (like logging and construction), traffic from endemic areas, and movement of bark mulch have all been implicated in the gradual spread of this organism to new areas.5

Infection is typically via inhalation of small basidiospores or desiccated yeast forms present in the environment. Rarely direct infections through skin wounds have been reported, most frequently in cats. A variety of virulence factors have been identified. The fungus can multiply at body temperatures. The large gelatinous capsule, which gradually enlarges in chronic infections, serves to prevent phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils. The capsule traps and depletes complement and circulating capsular antigens aid in the removal of selectins from endothelial surfaces, thus inhibiting migration of neutrophils into tissues. Melanin production helps to protect the yeast from host-induced oxidative injury and when present, appears to assist the organism in invading the central nervous system.7 It is interesting that although C. neoformans and C. gattii share many of the same virulence factors, C. gattii (especially types VGI, VGII, and possibly VGIII) most commonly causes infection in non-immunocompromised people and animals while C. neoformans primarily infects immune-compromised individuals.2 C. gattii is considered a primary pathogen, while C. neoformans is generally an opportunistic infection. The cause of this observation is unknown. It may be related to the level of environmental exposure, that is, immunocompromised individuals may have more exposure to C. neoformans than C. gattii. Host genetic factors and inherent resistances or susceptibility to cryptococcal infection may also play a role.2

Given that infection is typically via inhalation, in animals, clinical disease due to C. gattii infection most commonly presents as chronic rhinitis and pneumonia. Encephalitis, via direct invasion from the nasal cavity, or sometimes via hematogenous routes, may result in a wide range of neurologic clinical signs. Widespread systemic infection has been reported in affected animals. As mentioned, cutaneous granulomatous lesions typically resulting from wound contamination may also occur, most commonly in cats.

In other areas, wild and domestic animals have acted as sentinels in the early detection of C. gattii infection and clinical disease is often detected first in animals before human cases are identified. Because of this finding, Nova Scotia public health officials have been notified to include C. gattii infection on their list of differential diagnoses, and testing protocols for suspect cases have been established.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology/Microbiology

Atlantic Veterinary College

University of Prince Edward Island

www.avc.upei.ca

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, mild, with numerous yeast consistent with Cryptococcus sp.

JPC Comment:

Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii are both stunners, notable among the dimorphic fungi for their arresting, large capsule. While C. neoformans has been known and admired since it was first isolated from fermented peach juice in the 1890s, C. gattii, perhaps a bit more shy, waited until 1970 to be discovered in a leukemic patient and has, until its recent incursion in to the Northwest of Canada and the United States, stayed respectfully confined to a fairly narrow subtropical niche.3

Despite their differences in temperament, however, they both share, as a primary virulence factor, a carbohydrate-rich outer capsule composed primarily of glucuronoxylomannan with lesser amounts of galactoxylomannan.3 Far from being just a pretty adornment, the capsule is a dynamic and defensive structure. It can suppress the host immune response by downregulating cytokine and chemokine secretion in dendritic cells, inhibiting binding of complement component C3, frustrating phagocytosis, and preventing dessication in the environment.3,8

One of the more interesting attributes of the Cryptococcus capsule is its ability to switch phenotypes. Phenotype switching is an adaptive mechanism characterized by structural modifications to the capsule and the cell wall.3 Phenotype switching in C. gattii is a reversible change between two forms – a mucoid form and a smooth form – that occurs infrequently in vitro and in chronic infections.3 Typically, infection begins with mucoid form, but subsequent phenotype switching to the smooth form, which is characterized by reduced capsular polysaccharide, allows for penetration of the blood-brain barrier and dissemination to the brain; consequently, while both smooth and mucoid forms are found in pulmonary infection, only smooth variants are typically found in the brain.3

The importance of the capsule to Cryptococcus pathogenicity is best illustrated by the effects of its absence. Acapsular C. gattii strains are far less virulent, and are quickly recognized and killed by macrophages and dendritic cells.6 If, however, these acapsular strains have C. gattii capsular polysaccharide deposited on their surface, phagocytosis is hindered, the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines is not triggered, and the fungi are not cleared, confirming the key role that the capsule plays in immune evasion.8

Conference participants appreciated the straight-forward nature of this slide, which provides an embarrassment of visual fungal riches. Participants noted the minimal amount of granulomatous inflammation in section, which is much less than would be expected with other dimorphic fungal infections of this severity. Partipants hypothesized that this rather languid inflammatory response might be due to the cloaking of the Cryptococcus capsule. Participants also admired a mucicarmine stain which, while beautiful, also provoked some discussion on whether mucicarine was staining the capsule, the organism, or both. Participants noted that mucicarmine stains the capsule, while silver stains such as GMS can be used to highlight the organism and to evaluate the broad or narrow-based nature of the budding.

Participants discussed the size of the yeast which, in some cases, appeared to exceed the standard 5-10 um expected size for Cryptococcus gattii. This lead to a discussion of Titan cells, which are a unique adaptation of Cryptococcus species where they grow to unusually large size as another mechanism to evade phagocytosis. Finally, the efforts of some industrious participants were rewarded by the discovery of several unheralded nematode larvae within the examined section.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis centered around whether the diagnosis should refer to fungal organisms generally or Cryptococcus sp. specifically. The majority of participants felt strongly that, given the unique morphology, budding, and staining characteristics exhibited in section, this was a diagnosis that could confidently be made on H&E examination alone.

References:

- Chen S, Meyer W, Sorrell T. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(4):980-1024.

- Diti A, Carroll SF, Qureshi ST. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging cause of fungal disease in North America. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;840452.

- Dixit A, Carroll SF, Qureshi ST. Cryptococcus gattii: an emerging cause of fungal disease in North America. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;840452.

- Dylag M, Colon-Reyes RJ, Kozubowski L. Titan cell formation is unique to Cryptococcus species complex. Virulence. 2020;11(1):719-729.

- Epsinel-Ingroff A, Kidd SE. Current trends in the prevalence of Cryptococcus gattii in the United States and Canada. Infect Drug Resist. 2015;8:89-97.

- Frietas GJC, Santos DA. Cryptococcus gattii polysaccharide capsule: an insight on fungal-host interactions and vaccine studies. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51(9):2206-2209.

- Lester SJ, Malik R, Bartlett KH, Duncan CG. Cryptococcosis: update and emergence of Cryptococcus gattii. Vet Clin Pathol. 2011;40(1):4-17.

- Saidykhan L, Onyishi CU, May RC. The Cryptococcus gattii species complex: unique pathogenic yeasts with understudied virulence mechanisms. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(12):e0010916.