CONFERENCE 23, CASE 4

Signalment: 7 year, spayed female, giant schnauzer, Canis familiaris

History: This dog presented to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Veterinary Care for evaluation of an oral mass that was first noted 2 months prior to presentation. Physical exam revealed a pink, irregular mass at the gingiva between teeth 101-102. Computed tomography revealed marked osteolysis of the maxilla associated with the mass and enlarged mandibular and cervical lymph nodes, with no other signs of metastatic disease. A partial maxillectomy was performed and the maxilla was submitted for histologic examination.

Gross Pathology: The tissue sample submitted for histologic examination consisted of a section of right maxilla including teeth 101-104 and 201. A 0.4 x 1.2 x 1.8 cm pink, soft, exophytic mass expanded the gingiva dorsal to teeth 101-103 and extended to the rostral hard palate. The specimen was decalcified prior to sectioning.

Laboratory Results: A fine needle aspirate and cytology of the enlarged lymph nodes was diagnosed as consistent with lymphoid hyperplasia. A complete blood count was unremarkable. Serum biochemical abnormalities included globulins 3.9 g/dL (2.2-3.5), AST 82 U/L (21-53), ALT 227 U/L (4-87), cholesterol 487 mg/dL (149-319), and triglycerides 261 mg/dL (32-190).

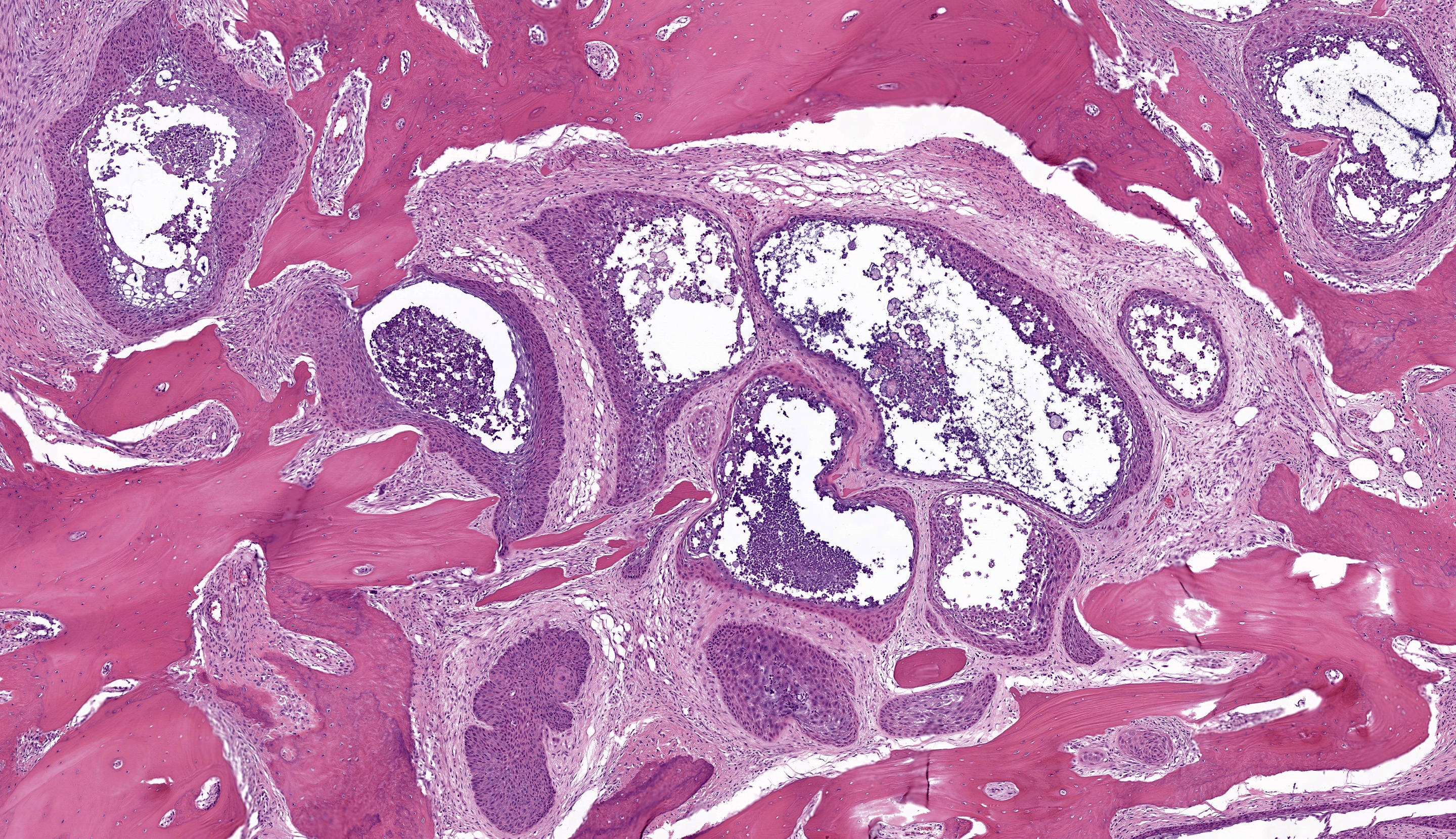

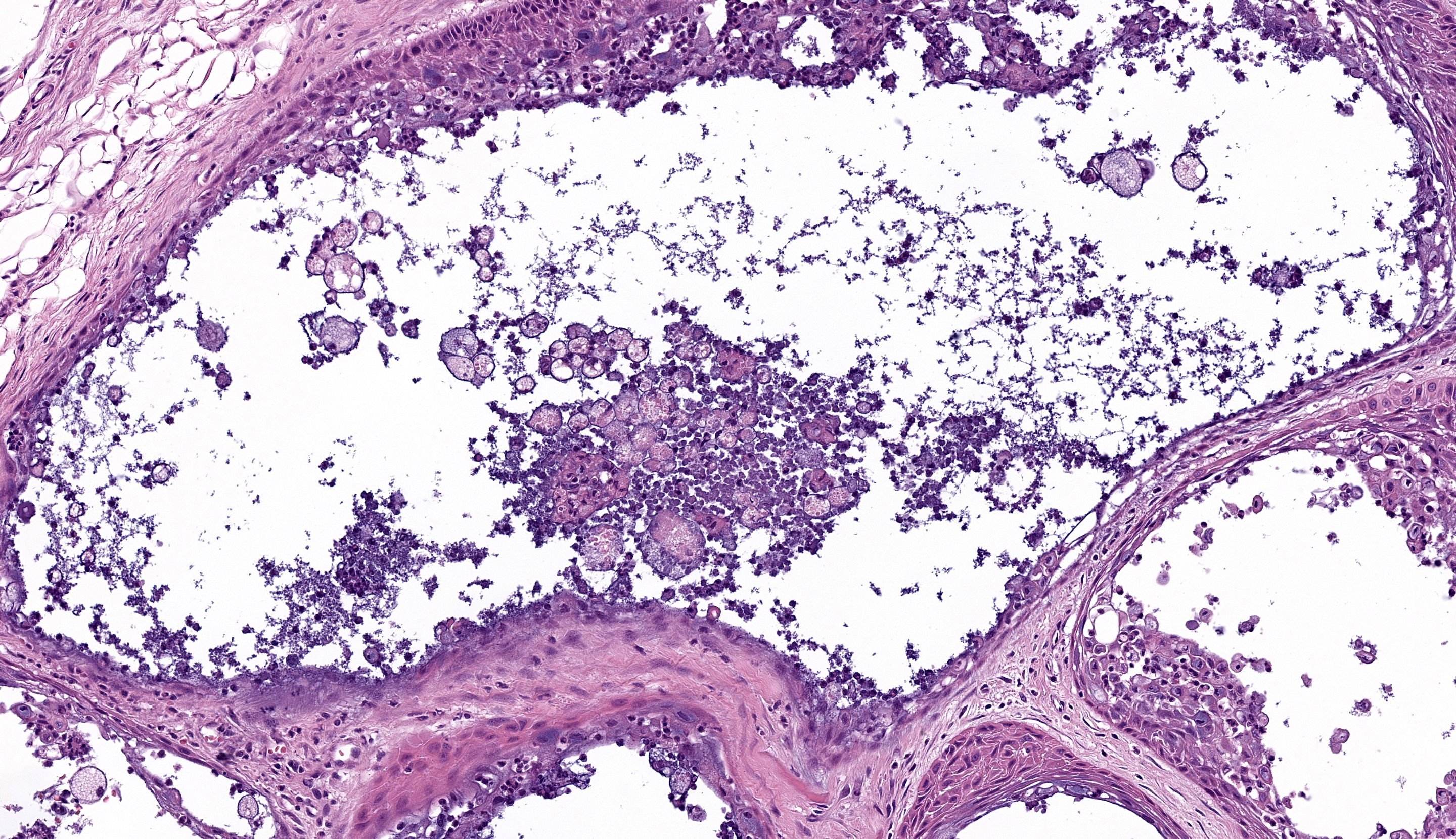

Microscopic Description: Gingiva. Arising from and markedly expanding the hyperplastic gingival epithelium and infiltrating the subepithelial stroma and alveolar bone is an unencapsulated, poorly demarcated, densely cellular exophytic and invasive mass. The mass is composed of neoplastic epithelial cells forming papilliferous projections into the oral cavity supported by a fibrovascular stalk and extending deep to the basement membrane to form nests and trabeculae supported by a moderate amount of fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells are polygonal with distinct cell borders and often prominent intercellular bridges, abundant pale to brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, a round to oval nucleus, finely stippled chromatin, and up to six prominent magenta nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are marked, there is occasional binucleation, and mitoses range from 2-4 per high-powered field (0.237 mm2). There is frequent individual cell necrosis and larger foci of central necrosis and vacuolation containing eosinophilic and karyorrhectic debris and neutrophils. The superficial stroma supporting the exophytic mass and its stalk are moderately expanded by clear space (edema) that contains small numbers of neutrophils and macrophages, and the deeper stroma is expanded by multifocal and coalescing regions of hemorrhage and small to moderate numbers of neutrophils that encircle and infiltrate the lobules of neoplastic cells. In regions of alveolar bone invasion, the margins of remaining bone are scalloped and occasionally lined by osteoclasts within Howship’s lacunae, and the affected bone contains multiple resting and reversal lines. In more severely affected regions, irregular trabeculae of pale woven bone are deposited on the pre-existing bone and are lined by plump osteoblasts.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis: Gingiva: Papillary squamous cell carcinoma

Contributor’s Comment: This case was diagnosed as a papillary squamous cell carcinoma (PSCC) arising from the gingival epithelium. PSCC is a subtype of oral SCC based on a classification scheme defined by the World Health Organization.1 In one retrospective study on canine oral SCC, PSCC comprised 6% of cases, compared to the more common conventional subtype which represented 82% of cases.9 Other subtypes of oral SCC that have been defined in dogs include basaloid, verrucous, adenosquamous, and spindle cell.1,9 At this time, subtyping is not routinely performed and it is unclear if there is an association between subtype and biologic behavior. In humans, PSCC tends to demonstrate local confinement and more feasible excision, and thus is associated with a more favorable prognosis.1

PSCC is differentiated from conventional SCC by the presence of neoplastic epithelial cells forming papillary fronds into the oral cavity, in addition to infiltrating the basement membrane into the subjacent stroma. Invasion beyond the basement membrane and keratinization can be minimal with this subtype, thus complicating the diagnosis in some cases.7,8 Other histologic features that may be seen with PSCCs include degeneration of apical neoplastic cells and abundant intraepithelial neutrophils.7 PSCCs can also occur as an intraosseous cavitated cyst within the bone (cavitating pattern), as opposed to the non-cavitating pattern featured in this case.7,8 Similar to this case, PSCCs appear to have a predilection for the gingiva of the dentate jaws, with the majority occurring on the rostral aspect.9,10

Risk factors for development of oral PSCC are not well-defined. This neoplasm has been primarily documented in young dogs,2,11 however multiple reports have shown that this subtype additionally affects adult and aged dogs, similar to this case.9,10 While papillomavirus infection has been associated with oral SCC in humans and cutaneous SCC in dogs, studies exploring the association between canine oral SCC and papillomavirus infection have not demonstrated a similar relationship.1, 3-5 Further, there is no evidence at this time that canine PSCC represents progression of an oral squamous papilloma.

Differential diagnoses in this anatomic location in dogs include canine acanthomatous ameloblastoma (CAA), oral squamous papilloma, and viral papillomas. CAA is differentiated from PSCC by the lack of characteristic papillary formations and by the presence of neoplastic odontogenic epithelium and stroma resembling periodontal ligament. While PSCC can macroscopically resemble oral squamous papilloma or viral papilloma, both entities can be histologically differentiated from PSCC by the confinement of neoplastic epithelial cells to the basement membrane and lack of cytopathic effects (for viral papillomas).6

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin

School of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathobiological Sciences

2015 Linden Drive

Madison, WI 53706

JPC Morphologic Diagnosis: Gingiva, incisive bone, and incisor: Papillary squamous cell carcinoma.

JPC Comment: The final case of this conference presents an interesting slide with a few subtle features to discover. Localization of this section to first or second incisor tooth is possible as the nasopalatine canal (incisive canal) is neatly outlined with a sickle of cartilage (lower right corner). Likewise, changes to the incisor tooth merit description as there is apparent lysis of dentin and repair as well as hypercementosis – we interpret the irregular shape and attachment of the tooth as a direct reaction to the neoplasm. We appreciated having a full thickness cross-sectional view to discuss these changes as typical biopsy specimens of this neoplasm are largely superficial.

Conference participants agreed with the contributor’s diagnosis of papillary SCC, though discussion of ancillary features and overlap with differential diagnoses still produced a fruitful discussion. The basic structure of this neoplasm is epithelial and we add salivary gland neoplasms as a consideration to the contributor’s differential list. CAA and papillary SCC are the most similar, though comedonecrosis (if present) is not consistent with CAA. We also noted several islands of epithelial cells outlined by ribbons of eosinophilic material that lacked osteocytes (dentin-like) which prompted consideration of an odontoma. Other portions of the neoplasm contain woven bone and osteoidal matrix induced by the neoplasm which could be confused with osteosarcoma or osteoinductive squamous cell carcinoma in a more limited biopsy sample. Once again, the value of lesion location, radiographs, and a biopsy sampling that includes the underlying invaded bone is critical for an accurate diagnosis.

References:

- Barnes L, Everson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. Tumours of the oral cavity and oropharynx. In: World Health Organization classification of tumors – pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. Lyon: IARC Press. 2005;163-208.

- Furuta K, Nishi K, Park C, et al. A case of papillary squamous cell carcinoma in the mandible of a young French bulldog. Can Vet J. 2021;62(11):1181-1184.

- Luff J, Rowland P, Mader M, Orr C, Yuan H. Two Canine Papillomaviruses Associated With Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Two Related Basenji Dogs. Vet Pathol. 2016;53(6):1160-1163.

- Mauldin EA and Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:711.

- Munday JS, French A, Harvey CJ. Molecular and immunohistochemical studies do not support a role for papillomaviruses in canine oral squamous cell carcinoma development. Vet J. 2015;204(2):223-225.

- Munday JS, Lohr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons; 2017:503-507,524.

- Murphy BG, Bell CM, Soukup JW. Tumors Arising from the Soft Tissues. In: Veterinary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: 2020: 139-143.

- Nemec A, Murphy BG, Jordan RC, Kass PH, Verstraete FJ. Oral papillary squamous cell carcinoma in twelve dogs. J Comp Pathol. 2014;150(2-3):155-161.

- Nemec A, Murphy BG, Kass PH, Verstraete FJ. Histological subtypes of oral non-tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma in dogs. J Comp Pathol. 2012;147(2-3):111-120.

- Soukup JW, Snyder CJ, Simmons BT, Pinkerton ME, Chun R. Clinical, histologic, and computed tomographic features of oral papillary squamous cell carcinoma in dogs: 9 cases (2008-2011). J Vet Dent. 2013;30(1):18-24.

- Stapleton BL, Barrus JM. Papillary squamous cell carcinoma in a young dog. J Vet Dent. 1996;13(2):65-68.