Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 11

20 November 2019

Charles W. Bradley, VMD,

DACVP

Assistant Professor, Pathobiology

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

4005 MJR-VHUP

3900 Delancey Street

Philapdelphia, PA, 19104

CASE III: H18-0008-92 (JPC 4122525).

Signalment: Unknown age (adult), European, male neutered, cat (Felis catus).

History: This cat was found dead in the street by a passerby and brought to the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Veterinaire d’Alfort (ChuvA) of the Ecole Nationale Veterinaire d’Alfort (EnvA). We were unable to find and contact the owner despite the presence of a microchip. As a consequence, no information regarding the medical history was available. A necropsy was performed for pedagogic purpose.

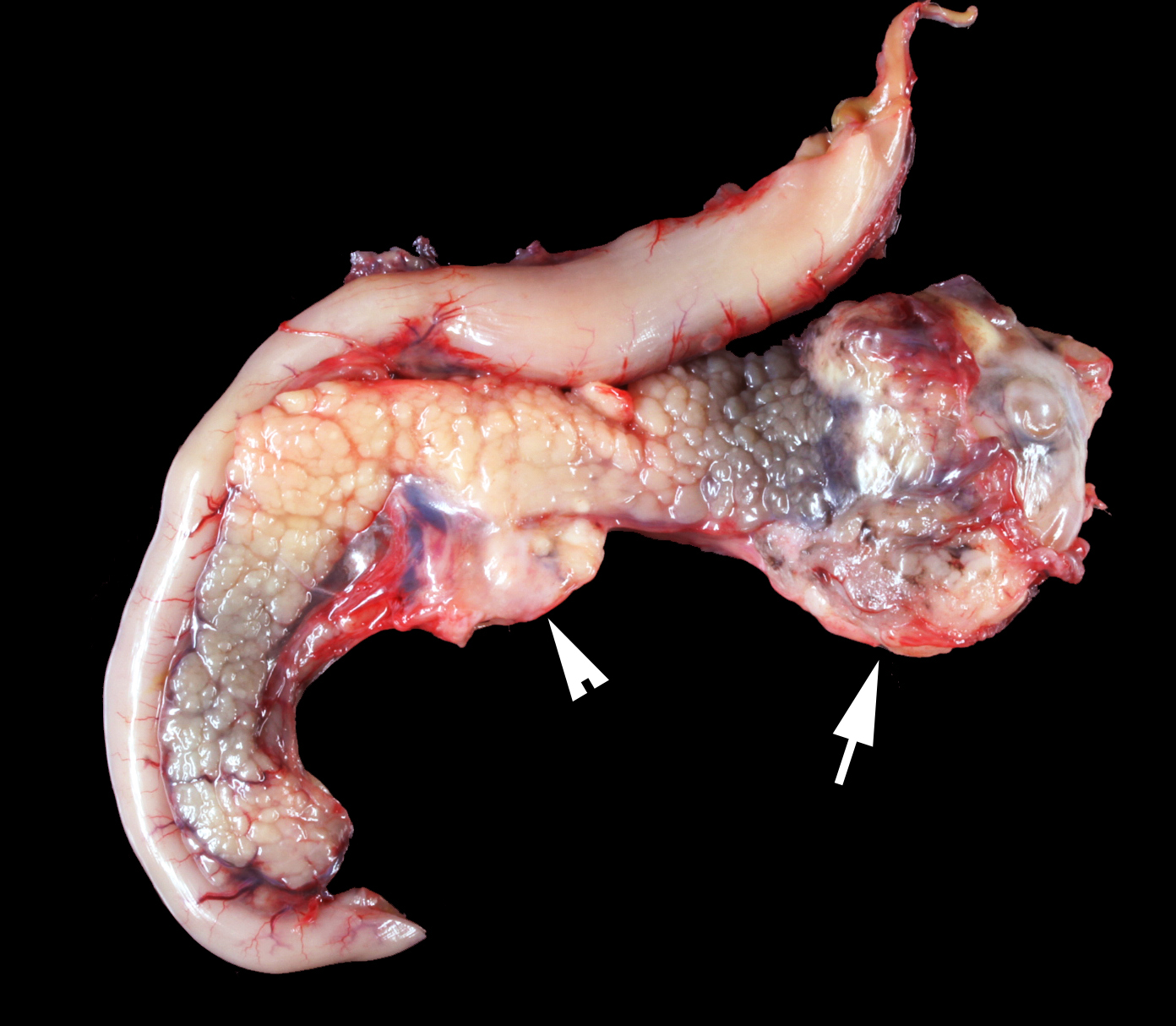

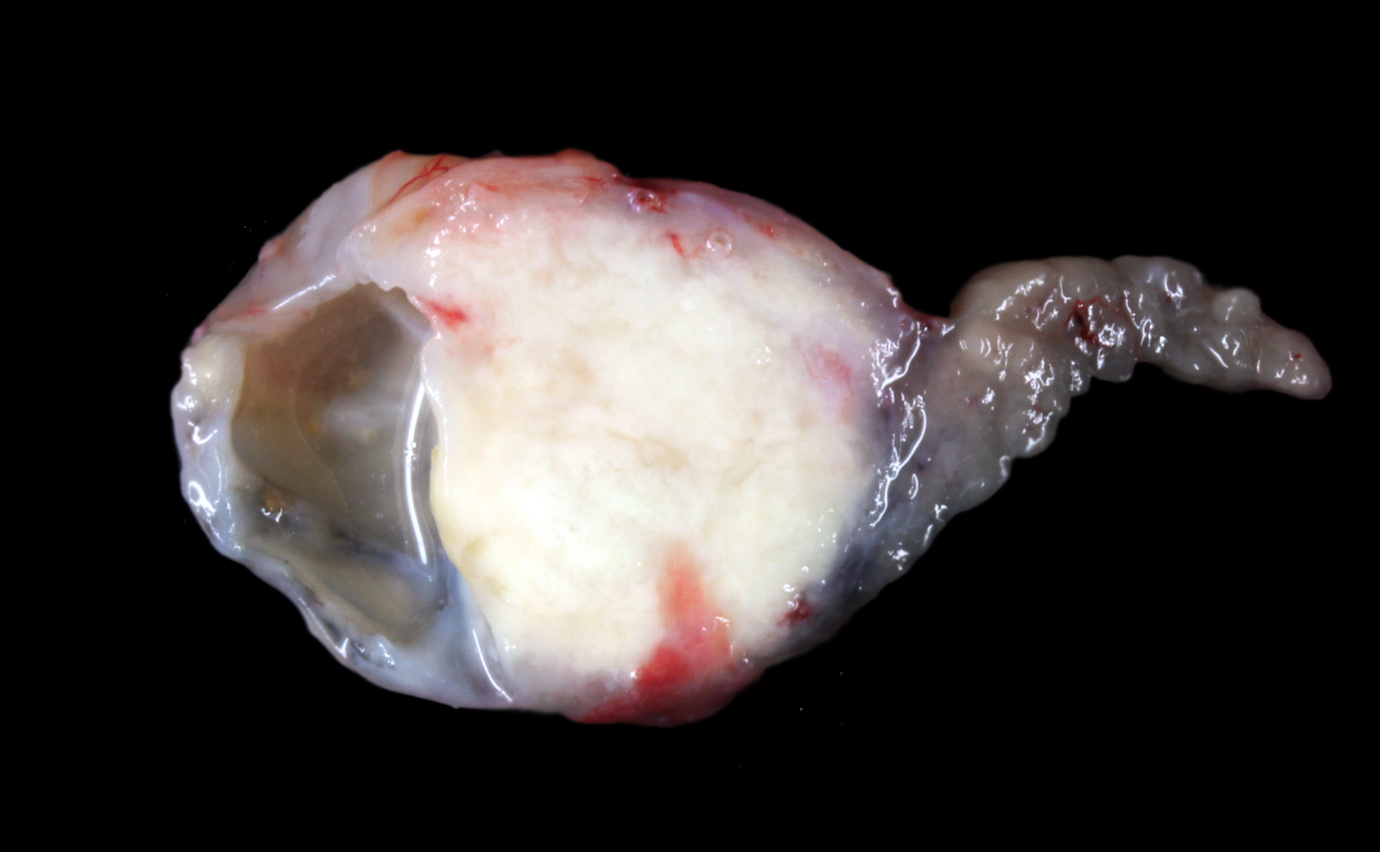

Gross Pathology: The animal was severely cachectic and dehydrated. The skin of the ventral abdomen, ventral thorax, ventral neck, flanks and all legs was alopecic, thin, smooth and focally erythematous. Remaining hairs could be easily removed. The pawpads were smooth, erythematous and sometimes shiny. A 2-cm-diameter, unencapsulated but rather well-demarcated, lobulated, firm, white mass was found at the extremity of the left pancreatic lobe. On cut section, the mass was cystic. The pancreatic lymph node was slightly enlarged, firm and white. Numerous firm, ill-demarcated, 1-3-cm in diameter, often umbilicated, white masses were found in the liver and on the abdominal side of the diaphragm.

Laboratory results:

None.

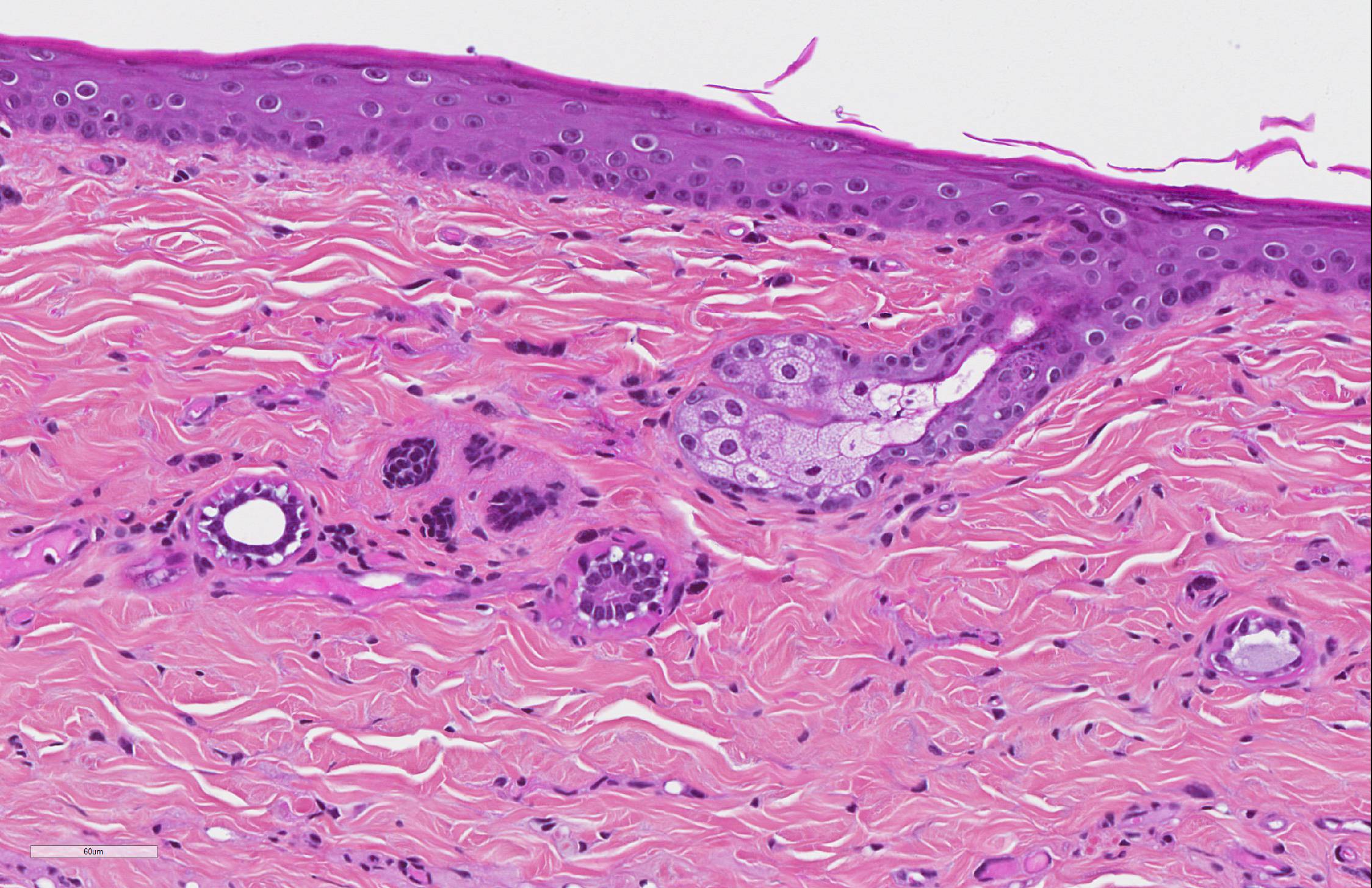

Microscopic Description:

SKIN: The main dermatopathologic pattern was non-inflammatory adnexal atrophy.

The epidermis was slightly and diffusely acanthotic. The stratum corneum was diffusely thin, compact and orthokeratotic, with focally areas of parakeratosis. There was diffuse and severe follicular atrophy of hairless telogen type. Hair follicles were reduced to thin and tortuous epithelial cords surrounded by a thick, homogenous and glassy sheath of collagen. Sebaceous and apocrine glands were present and only minimally atrophic.

There was a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells. The hypodermis was diffusely and severely atrophic with only few and small remaining adipocytes.

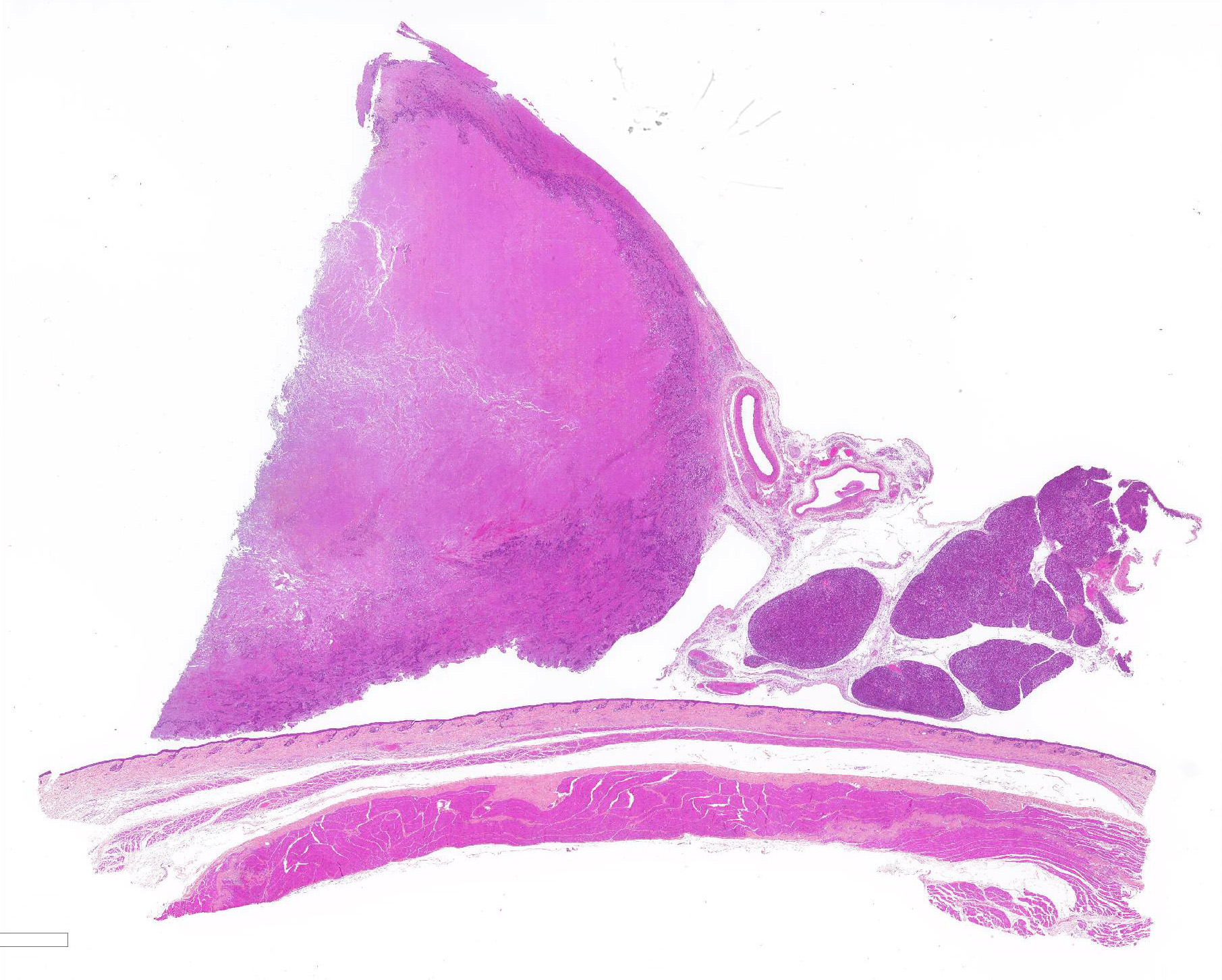

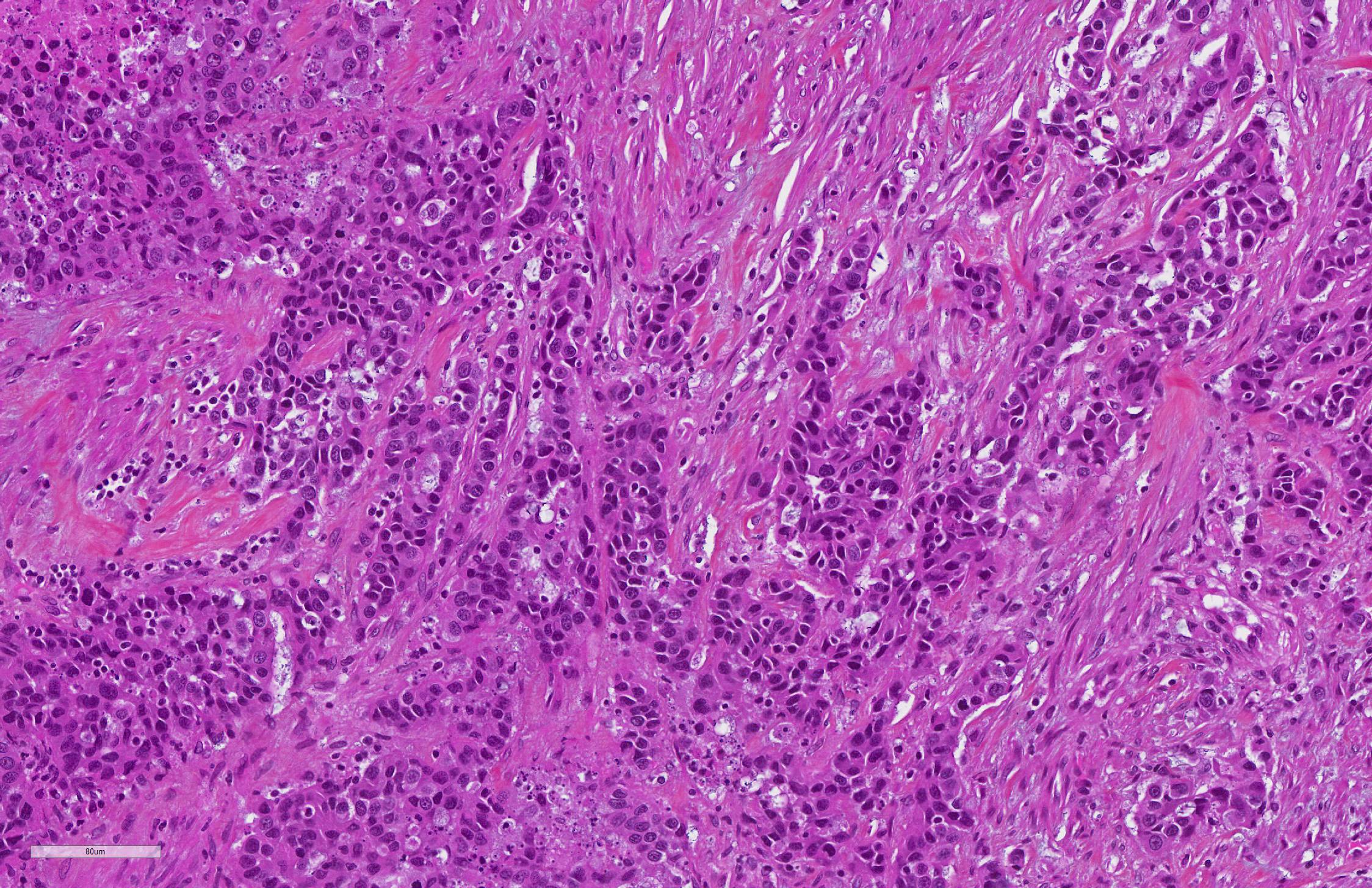

PANCREAS: A rather well-circumscribed but infiltrating and only partially encapsulated, highly cellular neoplasm developed in the pancreas. Neoplastic epithelial cells formed cords and nests supported by a moderately abundant fibrovascular stroma. Cells were polygonal to cuboidal, had a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, a scant brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm and a central to paracentral round nucleus with a prominent eosinophilic nucleolus and coarse chromatin. Cytonuclear atypias were marked with anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, occasional binucleation, hyperchromatic nuclei. The mitotic count was moderate (7 mitoses per 10 high-power 0,237-mm²-fields). A large central area of necrosis was present. No lymphovascular emboli were found but several images of perineural invasion were present at the periphery.

In the remaining pancreatic parenchyma, the lobulation was prominent due to a moderate to marked thickening of interlobular septa by fibrosis and multifocal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. Affected lobules often had rounded borders. Some pancreatic ducts were dilated and/or filled with degenerated neutrophils. There were also multiple foci of exocrine lobular hyperplasia.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

SKIN: Follicular atrophy, severe, diffuse, with telogen hairless follicles and diffuse slight epidermal acanthosis and compact stratum corneum, findings consistent with feline paraneoplastic alopecia.

PANCREAS:

1. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

2. Pancreatitis, neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic, chronic-active, multifocal, moderate with interstitial fibrosis (chronic interstitial pancreatitis).

3. Exocrine nodular hyperplasia.

Name of the disease: Feline paraneoplastic alopecia.

Contributor Comment: Paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) are non-neoplastic but neoplasm-associated disorders that cannot be readily explained neither by the location of the primary tumor or its metastases, nor by the elaboration of hormones indigenous to the tissue from which the tumor arose.7,11,14 PNS can be associated to both benign or malignant tumors and some PNS are highly specific of particular tumors.7,11 PNS are important to recognise because they can be the first sign of a tumor, can be used as a marker of the disease (as such, they may indicate recurrence) or because they can cause significant clinical problems.6 If the tumor is removed, resolution of the PNS usually occurs. Recurrence or persistence of a PNS may indicate tumor recurrence, incomplete excision and/or metastases.

In people, it is expected that 10-50% of patients with a malignancy will experience at some point a PNS.7,14 In veterinary medicine, the exact frequency of PNS is unknown but several cutaneous PNS of internal tumors (mainly cancers) have been described and are summarized in table 1. More cutaneous PNS are described in humans.14

In many veterinary textbooks and papers, we found that nodular dermatofibrosis associated with renal cystadenocarcinoma in dogs is often described as a cutaneous PNS.9,11,14 We believe that this disease should be regarded as a genetic tumor syndrome in which dermatofibromas represent markers of the disease rather than PNS. Indeed, dermatofibromas usually precede, rather that follow, renal cystadenocarcinomas and thus appear to develop independently from them.3,14 Furthermore, there are evidence that dermatofibromas develop first because they reflect haploinsufficiency in dermal fibroblasts whereas renal cystadenocarcinomas develop later because they require a second-hit mutation (loss of heterozygosity) in the Birt-Hogg-Dube gene. This resembles fibrofolliculomas associated with renal cancers in Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome in humans.3

|

PNS |

Most common associated tumor |

Main dermatologic features |

Main cutaneous histopathological features |

Comments |

|

Feline paraneoplasic alopecia |

Pancreatic or biliary carcinoma |

Progressive alopecia, easily epilated hair, glistening skin, sometimes footpad involvement |

Nonscarring alopecia with follicular telogenization, miniaturization and atrophy |

Also weight loss. Late in the course of malignancy. Possible secondary infections (Malassezia spp.) |

|

Feline thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis |

Thymoma |

Progressive erythema and scaling, alopecia, waxy debris between digits and in nail beds |

Cell-poor hydropic interface dermatitis with hyperkeratosis. Sebaceous gland often absent. |

Assumed to be immune-mediated (resembles graft-versus-host reaction) |

|

Feminization syndrome |

Testicular tumors, in particular Sertoli cell tumors |

Bilateral symmetrical alopecia, linear preputial dermatosis, gynecomastia, pendulous prepuce |

Epidermal thinning, follicular keratosis and atrophy, sebaceous gland atrophy |

Also myelosuppression and behavioral changes. Believed to be related to sex hormone aberration (hyperestrogenism and/or testosterone:oestrogen imbalance) |

|

Superficial necrolytic dermatitis |

Glucagonoma |

Foot pad hyperkeratosis, alopecia and erosions with crusts on pressure points, mucocutaneous junctions, the muzzle, perineal area and feet |

Parakeratosis, keratinocytic edema/necrosis and basal cell hyperplasia (French flag or red, white and blue epidermal appearance) |

Also found in cases of hepatocutaneous syndrome which is more frequent. |

|

Para-neoplastic pemphigus |

Lymphoma, splenic sarcoma (other?) |

Erythematous vesiculo-bullous lesions of head, trunk and limbs |

Suprabasal cleft-forming acantholysis, dyskeratotic or necrotic keratinocytes at all epidermal levels, basal vacuolization, intense epidermal exocytosis of inflammatory cells |

Also severe, erosive stomatitis with involvement of upper digestive and respiratory tracts. One reported case in a dog associated with mediastinal lymphoma |

Table 1: Main features of cutaneous PNS in dogs and cats.7,11

Feline

paraneoplastic alopecia has been associated with pancreatic adenocarcinoma,

bile duct carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, neuroendocrine pancreatic

carcinoma, intestinal adenocarcinoma and hepatosplenic plasma cell tumor, the

first one being the most frequent cause.1,4,9,14 In most cases,

paraneoplastic alopecia is recognized in advanced stages of the disease and

affected cats are usually euthanized due to an extremely poor prognosis.

The mechanism underlying feline paraneoplastic alopecia has not been elucidated. In the rare cases in which excision of the primary tumor was performed, hair regrowth was observed but alopecia then returned when metastases developed.4 Interestingly, alopecia has been described in a woman with a bile duct carcinoma who presented a round alopecic area just on the top of the skull. A complete removal of the liver tumor allowed hair to grow back until metastases developed.2

In cats, differential diagnoses for acquired alopecia should include dermatophytosis, demodicosis due to Demodex cati, immune-mediated lymphocytic mural folliculitis, pseudopelade and vasculitis for primary alopecia. Cheyletiella blakei, Notoedres cati, Demodex gatoi, allergic disease, cutaneous infections with bacteria and/or fungi or fleas should be considered as a cause for secondary alopecia. Other causes such as telogen effluvium, hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism occur very rarely in cats.1,4

Interestingly, in this case, the remaining pancreatic parenchyma had lesions of chronic pancreatitis. Chronic inflammation is well known as a predisposing factor for cancer and there are numerous examples: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis causing gastric lymphoma in humans, Spirocerca lupi-infestation causing esophageal sarcomas in dogs, etc.7,11 Many studies have found a link between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic malignancy in humans.5,12,13,15,16 It is thus tempting to speculate that the chronic pancreatitis may have favored the development of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma in this case.

Contributing Institution:

Unite d’Histologie et d’Anatomie pathologique, BioPole Alfort, Departement des Sciences Biologiques et Pharmaceutiques, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort

JPC Diagnosis: 1. Pancreas: Pancreatic exocrine carcinoma.

2. Pancreas: Pancreatitis, interstitial, subacute, diffuse, mild, with acinar

atrophy.

3. Pancreas, islets: Amyloidosis, diffuse, mild.

4. Haired skin, follicles and apocrine glands: Atrophy, diffuse, severe with

mild atrophy of the stratum corneum.

5. Subcutis, fat and skeletal muscle: Atrophy, diffuse, severe.

JPC

Comment: The

contributor has provided an excellent review of feline paraneoplastic

alopecias, and their speculation on the exclusion of nodular dermatofibrosis

from the classification of paraneoplastic syndromes as well as on the potential

inflammatory origin of the pancreatic neoplasm in this cat are logical and

appear sound.

Pancreatic exocrine neoplasia is an uncommon entity in dogs and cats, although

hyperplastic lesions of the exocrine pancreas is very common in older

individuals. Subtypes of pancreatic exocrine carcinoma include ductal, acinar,

and less common hyalinizing, clear cell, and undifferentiated.10

These neoplasms are subtyped by the primary discernable pattern of the

neoplastic cells. In this particular case, as the majority of the neoplasm is

necrotic, and only cells infiltrating the capsule are viable, a definitive

pattern is not available, making subtype of this neoplasm untenable in this

particular case. A 2011 report suggested that loss of expression of tight

junction protein claudin-4 might result in cellular detachment and invasion in

poorly-differentiated neoplasm and was suggested as a marker of poorly

differentiated tumors.6

In cats, this is a neoplasm of older animals (median 11.6 years).8,10

They progress rapidly with animals presenting with weight loss, and anorexia,

occasionaly vomiting, and a palpable abdominal mass. 8,10

Involvement of the liver or bile duct by metastatic foci or explants may result

in icterus or elevated liver enzymes. In the cat, these are usually solitary

masses, but may also infiltrate and efface the pancreas as well. 8,10

Untreated, the medial survaval time is 97 days, while animals receiving

surgical treatment or chemotherapy survive an average of 165 days. 8

One retrospective study identified diabetes mellitus in 15% of cats with

pancreatic malignancies.10

In dogs, pancreatic adenocarcinomas present with similar signs, and may also present either as solitary masses or infiltrate the pancreas. Unlike the cat, elevated levels of amylase and lipase may be seen as a result of pancreatitis.8 Metastasis, often to the liver and local lymph nodes is seen in the majority of cases. Hyalinizing pancreatic adenocarcinoma, a rare variant (WSC 2013-2014, Conference 2, Case 4), occasionally arises as a solitary mass in the right lobe of the pancreas. The nature of the hyalinized stroma in these tumors is not known, but it is not amyloid, as it does not stain with antibodies for serum amyloid A, light chains, amylin, or alpha-1-antitrypsin.

During the

discussion, the moderator noted that in the skin, while the follicles and

apocrine glands were markedly atrophic, the sebaceous glands were of normal

size, which is characteristic for this condition. These cats may also have

concurrent Malassezia infections as a result of altered lipid profiles

of keratinocytes. The moderator suggested a limited differential for the skin

lesion, between this condition and hypercortisolism which also has severe

atrophy of follicles and adnexa, but also may have skin fragility due to loss

of dermal collagen as well.

References:

1. Affolter V, Gross TL, Ihrke P, Walder E. Atrophic diseases of the adnexa. In: Skin diseases of the dog and cat: clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. Blackwell Publishing; 2005:480â517.

2. Antoniou E, Paraskeva P, Smyrnis A, Konstantopoulos K. Alopecia: a common paraneoplastic manifestation of cholangiocarcinoma in humans and animals. Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006217âbcr2012006217.

3. Gardiner DW, Spraker TR. Generalized Nodular Dermatofibrosis in the Absence of Renal Neoplasia in an Australian Cattle Dog. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:901â904.

4. Grandt L-M, Roethig A, Schroeder S, et al. Feline paraneoplastic alopecia associated with metastasising intestinal carcinoma. J Feline Med Surg Open Rep. 2015;1:205511691562158.

5. Hamada S, Masamune A, Shimosegawa T. Inflammation and pancreatic cancer: disease promoter and new therapeutic target. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:605â617.

6. Jakab CS, Rusvai M, Demeter Z, , Szab³ Z, Kulka J. Expression of claudin-4 molecule in canine exocrine pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:1121-1126.

7. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Neoplasia. In: Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Elsevier; 2014:189â242.

8. Linderman, MJ, Brodsky EM, Lorimier LP, Clifford CA, Post GS. Feline exocrine pancreatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 34 cases. Vet Comp Oncol 2018; 11:208-212.

9. Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Vol. 1, Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmerâs pathology of domestic animals. Grant, M M; 2007:509â736.

10. Munday JS, Lohr CV, Kiupel M. Tumors of the alimentary tract. In: Tumors of Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons 2017: 597-600.

11. Newkirk KM, Brannick EM, Kusewitt DF. Neoplasia and Tumor Biology. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. Elsevier; 2017:289â321.

12. Pinho AV, Chantrill L, Rooman I. Chronic pancreatitis: A path to pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:203â209.

13. Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Morselli-Labate AM, Maisonneuve P, Pezzilli R. Pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis; aetiology, incidence, and early detection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:349â358.

14. Turek MM. Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes in dogs and cats: a review of the literature. Vet Dermatol. 2003;14:279â296.

12. Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic Pancreatitis: Challenges and Advances in Pathogenesis, Genetics, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557â1573.

13. Xu Z, Vonlaufen A, Phillips PA, et al. Role of Pancreatic Stellate Cells in Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2585â2596.