Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 18

February 7th, 2018

CASE II: NP-20/17 (JPC 4102669)

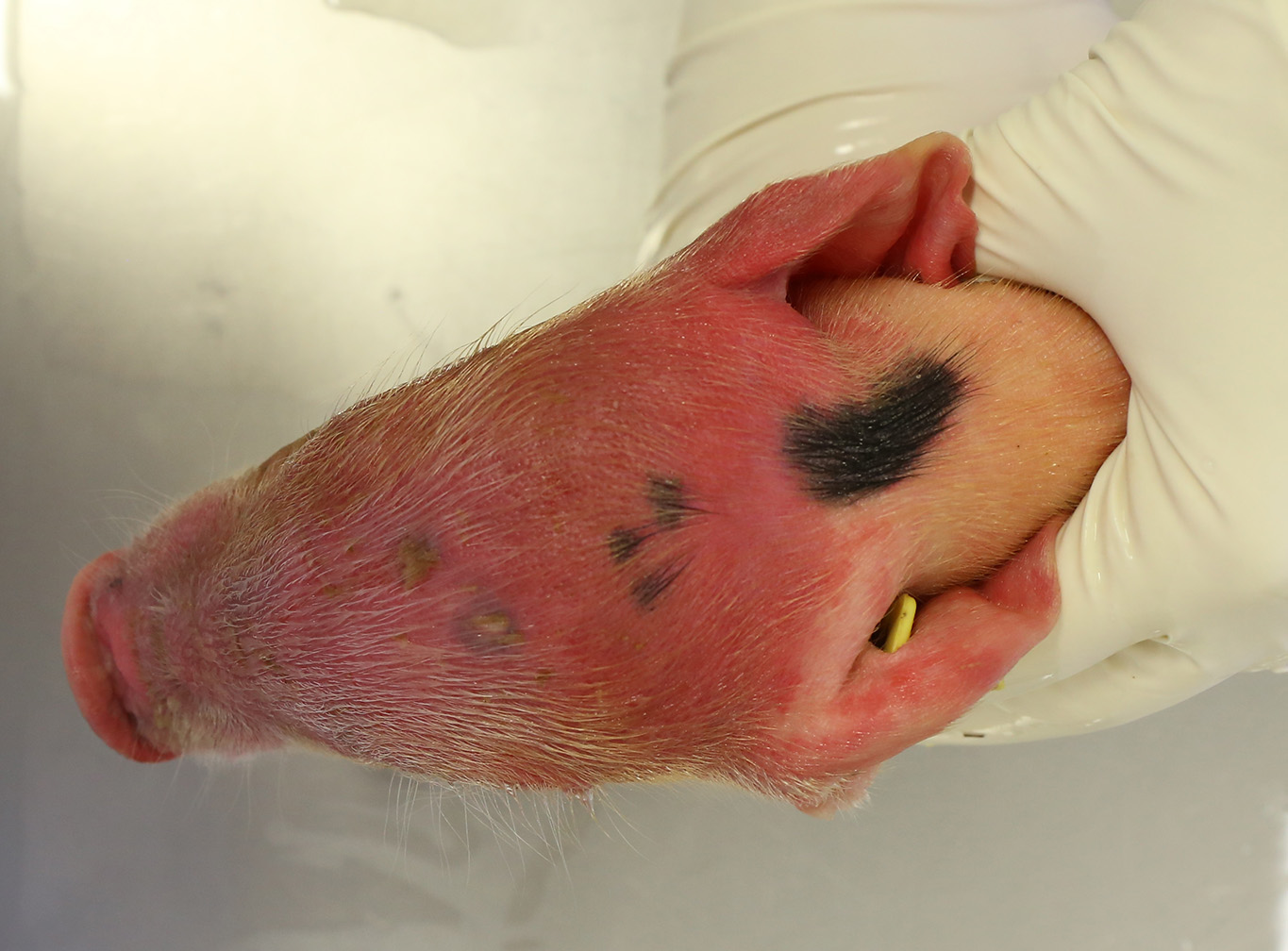

Signalment: 3-day-old male piglet (Sus scrofa domesticus), porcine.

History: This was one of two piglets that came from a farm of 1100 sows and 3000 suckling piglets. 24-48 hours post-birth the piglets showed diffuse inflammation and cyanosis of the head, lethargy and they died 12 to 24 hours after the first clinical signs appeared. The clinical signs affected one or few of the piglets from a same litter and all the affected animals died. The problem occurred in litters of both gilts and sows. Teeth shaving or trimming of piglets is not a general procedure in this farm.

Gross Pathology: Both piglets submitted for necropsy presented an intense and diffuse swelling of the skin and the subcutaneous tissue of the face, the head and the cranial portion of the neck. The skin also had a diffuse reddish coloration. In the frontal aspect of the face, in the cutaneous surface there were two small irregular epithelial erosions covered with crusts. After removing the skin of the head and neck there was moderate amount of clear, fluid to gelatinous material in the subcutaneous tissue and the hypodermis, interpreted as edema. The regional lymph nodes (submandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes) appeared diffusely edematous and reddened. In both animals teeth were intact. In the rest of the body there were not significant alterations. The stomach was filled with clotted milk.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

Microbiology: Pasteurella multocida was isolated on bacterial culture of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, liver and spleen of both animals.

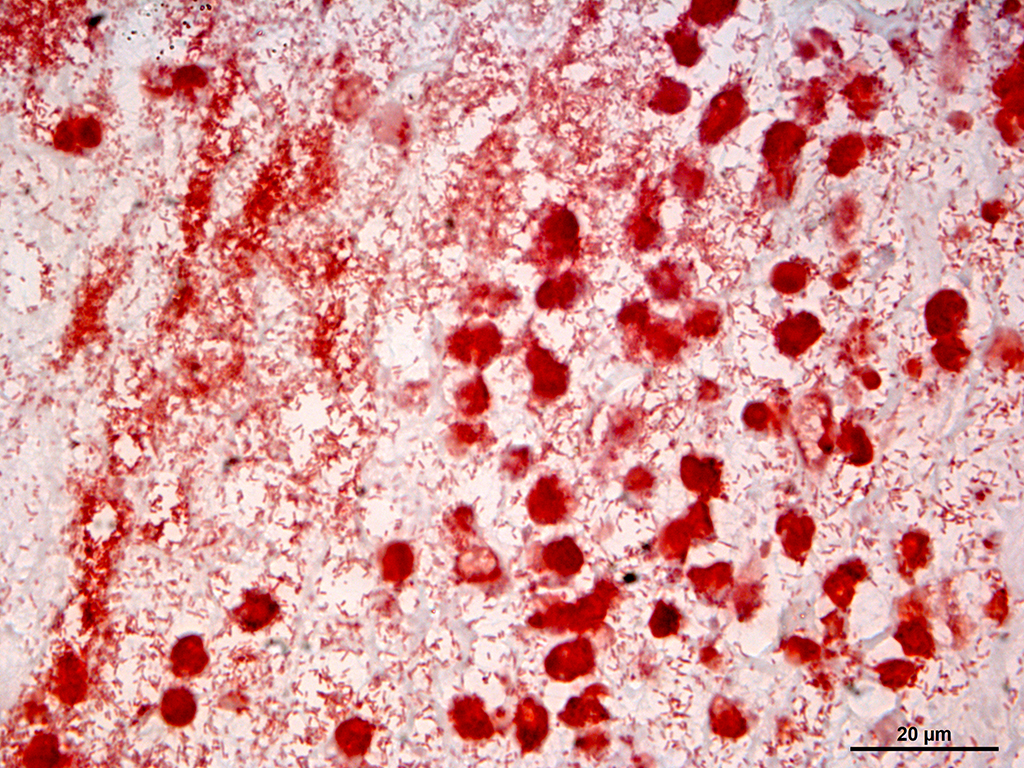

Tissue gram stain: Abundant numbers of coccobacillary gram-negative bacteria in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. There were also large quantities of gram positive bacterial cocci on the epidermal surface.

Microscopic Description:

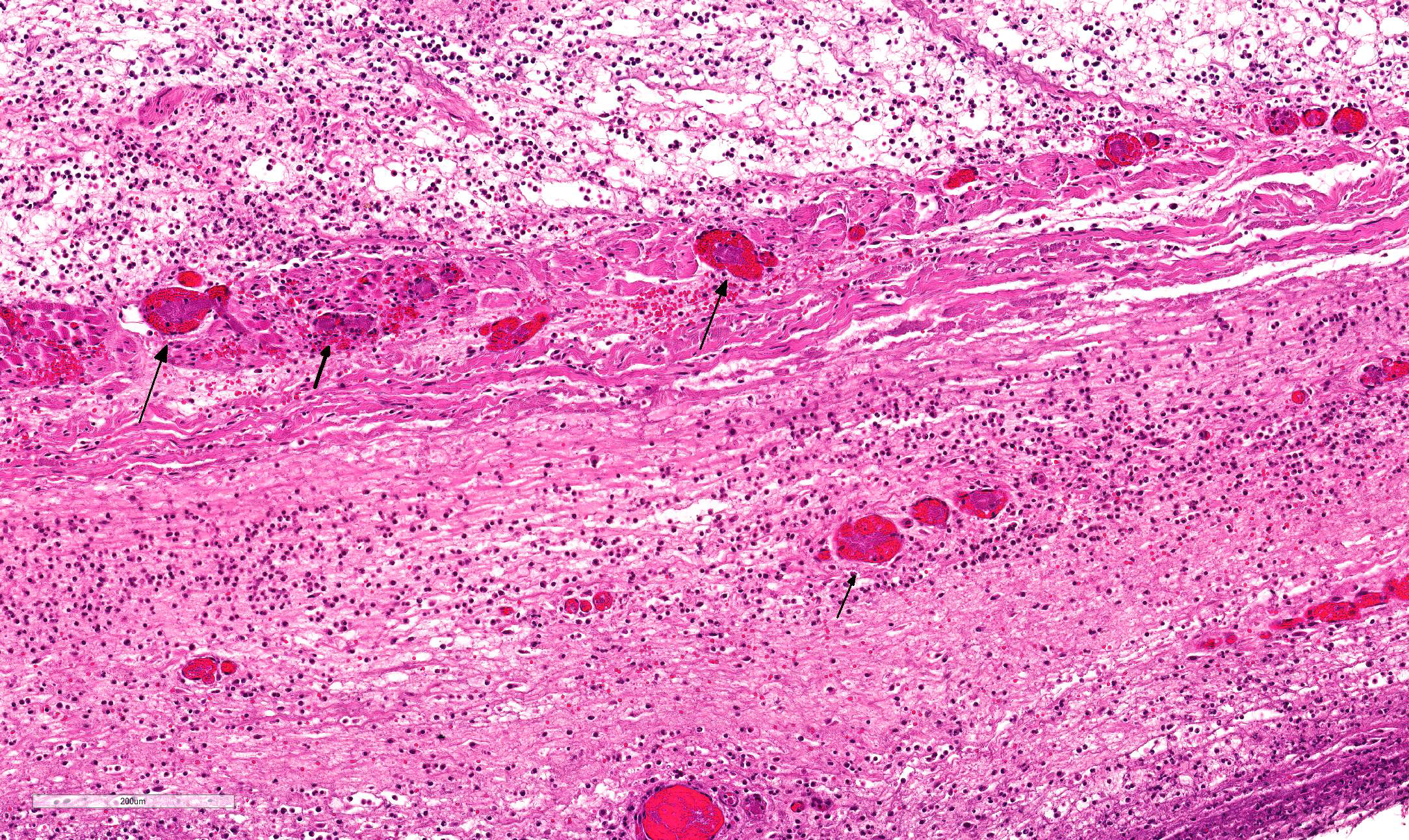

Multifocally, the skin shows areas of loss of continuity of the epidermis (ulcers) and substitution by moderate amounts of necrotic debris, degenerated neutrophils, extravasated erythrocytes and occasional aggregates of cocci (serocellular crust). The dermis is entirely expanded by abundant interstitial edema and hemorrhage, together with large amount of inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly by neutrophils and in lesser extend macrophages and lymphocytes that reach the subcutaneous muscle and adipose tissue. In these localizations, there are abundant coccobacilli distributed diffusely and forming small clusters. Additionally the deep dermis there are multifocal areas of necrosis composed by eosinophilic amorphous material with cellular debris and abundant bacterial colonies. The blood vessels are markedly congested and contain abundant bacterial emboli in their lumen.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Haired skin: Dermatitis, cellulitis and panniculitis, necrotizing and suppurative, diffuse, acute, severe with gram-negative bacteria consistent with Pasteurella multocida.

- Haired skin: Dermatitis, ulcerative and suppurative, multifocal, acute, severe with gram-positive bacteria.

Contributor’s Comment: This case is consistent with a condition known as facial necrosis (facial pyemia),2,8 a common condition in suckling pigs less than one week of age characterized by bilateral necrotic ulcers that are often covered by hard brown crusts and that extent from the side of the face to the lower jaw area, especially on the lips and cheeks.

The condition is the result of infection of wounds inflicted by piglets on each other with their sharp teeth while suckling from the sow. Lacerations to the sides of the face become infected with organisms such as F. necrophorum, Streptococcus spp., and B. suis, among others.2,5

In this case, none of the above bacteria was cultured but Pasterella multocida was isolated in pure culture. This case represents an especially severe form of the disease, complicated by cellulitis and panniculitis. This may be associated with the effects of Pasteurella multocida dermonecrotic toxin.12

Facial necrosis is commonly seen in large litters and especially in the disadvantaged weaker piglets and when milk letdown is slow such as when sows suffer from mastitis, metritis, agalactia syndrome (MMA syndrome). In these cases there is an increase in competitition between piglets and lacerations and bites do occur.

Since 2013, there is a European legislation that regulates the shaving or trimming of teeth in suckling piglets. The aim of the regulation is to avoid teeth shaving as a general procedure, but it can be still considered in specific or individual litters when a facial necrosis situation suddenly occurs.

Facial necrosis occurs during the first few days of life and any number of piglets in a litter can be affected. Initially, lesions can be seen as striated lacerations caused by bites from other piglets. The lesions become infected, resulting in shallow ulcerations covered with hard browns crusts and can predispose to outbreaks of exudative epidermitis.

In this case there was a septicemic pasteurellosis since Pasteurella multocida was isolated from skin, liver and spleen. Septicemic pasteurellosis has a sudden onset with mortality ranging from 5% to 40%. Clinical signs include high fever, dyspnea, prostration, edema of the throat and lower jaw and purplish discoloration of the abdomen, suggesting endotoxic shock.5,10,12

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin and subcutis: Dermatitis and cellulitis, necrosuppurative, diffuse, severe with vasculitis, thrombosis, and numerous intravascular and extracellular bacilli, piglet (Sus scrofa domesticus), porcine.

Conference Comment: Pasteurella multocida, a gram-negative nonmotile coccobacillus, was first identified in 1878 as the causative agent of fowl cholera. It was isolated by Louis Pasteur in 1880, in whose honor it is named.9 Strains of P. multocida are currently divided into five serogroups (A, B, D, E, F) based on capsular composition and somatic serovar.6 P. multocida is a ubiquitous pathogen and is often part of the normal respiratory flora in mammals, but can cause a wide range of diseases such as: fowl cholera in poultry, atrophic rhinitis in pigs12, pneumonia in various species, and bovine hemorrhagic septicemia in cattle and buffalo.7 In humans, it is a common cause of zoonotic infections following animal bites or scratches.

As a gram-negative bacterium, P. multocida expresses the variable carbohydrate surface molecule, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and a polysaccharide capsule which has been shown to aide in resistance to phagocytosis by host immune cells (serotypes A and B) as well as complement-mediated lysis (serotype A).1,4 Strains that cause atrophic rhinitis (serotype D) also produce P. multocida toxin (PMT) which is a dermonecrotic toxin encoded on bacteriophages that initially stimulates osteoblasts. Then, as toxin levels increase, PMT blocks the function of osteoblasts and increases the activity of osteoclasts, leading to osteolysis of nasal turbinates.12

In a laboratory setting, P. multocida will grow at 37 °C on blood, chocolate, or high-strength agars, but will not grow on MacConkey agar. Bacterial growth is accompanied by a “mousy” odor due to metabolic products produced by the bacterium. Environmental endurance can be strengthened by adding salt.3

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Pathology Department

Veterinary Faculty

Autonomous University of Barcelona

08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain

References:

- Boyce JD, Adler B. The capsule is a virulence determinant in the pathogenesis of Pasteurella multocida M1404 (B:2). Infect Immun. 2000;68(6):3463-3468.

- Cameron R. Integumentary system: Skin, hoof and claw. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2012:257.

- Casolari C, Fabio U. Isolation of Pasteurella multocida from human clinical specimens: first report in Italy. European Journal of Epidemiology. 1988;4(3):389-390.

- Chung JY, Wilkie I, Boyce JD, Townsend KM, Frost AJ, Ghoddusi M, Adler B. Role of capsule in the pathogenesis of fowl cholera caused by Pasteurella multocida serogroup A. Infect Immun. 2001;69(4):2487-2492.

- Hargis AM, Myers S. The integument. In: Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:1129.

- Kuhnert P, Christensen H. Pasteurellaceae: Biology, Genomics and Molecular Aspects. Bern, Switzerland: Caister Academic Press; 2008:34-39.

- Lopez A, Martinson SA. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleurae. In: Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:528, 530, 542, 550.

- Nimmo-Wilkie J. Skin. In: Sims LD, Glastonbury JRW. Pathology of the Pig- A Diagnostic Guide. 1st ed. Barton, A.C.T.: Pig Research and Development Corporation, Victoria, Australia. 1996:351.

- Pasteur L. The attenuation of the causal agent of fowl cholera. 1880:126-131.

- Register KB, Brockmeier SL, de Jong MF, Pijoan C. Pasteurellosis. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, eds. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2012:803.

- Ujvári B, Szeredi L, Pertl L, Tóth G, Erdélyi K, Jánosi S, Molnár T, Magyar T. First detection of Pasteurella multocida type b:2 in Hungary associated with systemic pasteurellosis in backyard pig. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica. 2015;63:141–156.

- Zachary J F. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: Zachary JF. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2017:173-174.