Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 1

August 22nd, 2018

CASE III: PV2017 (JPC 4102985).

Signalment: Female NOD-SCID mouse

History: N/A.

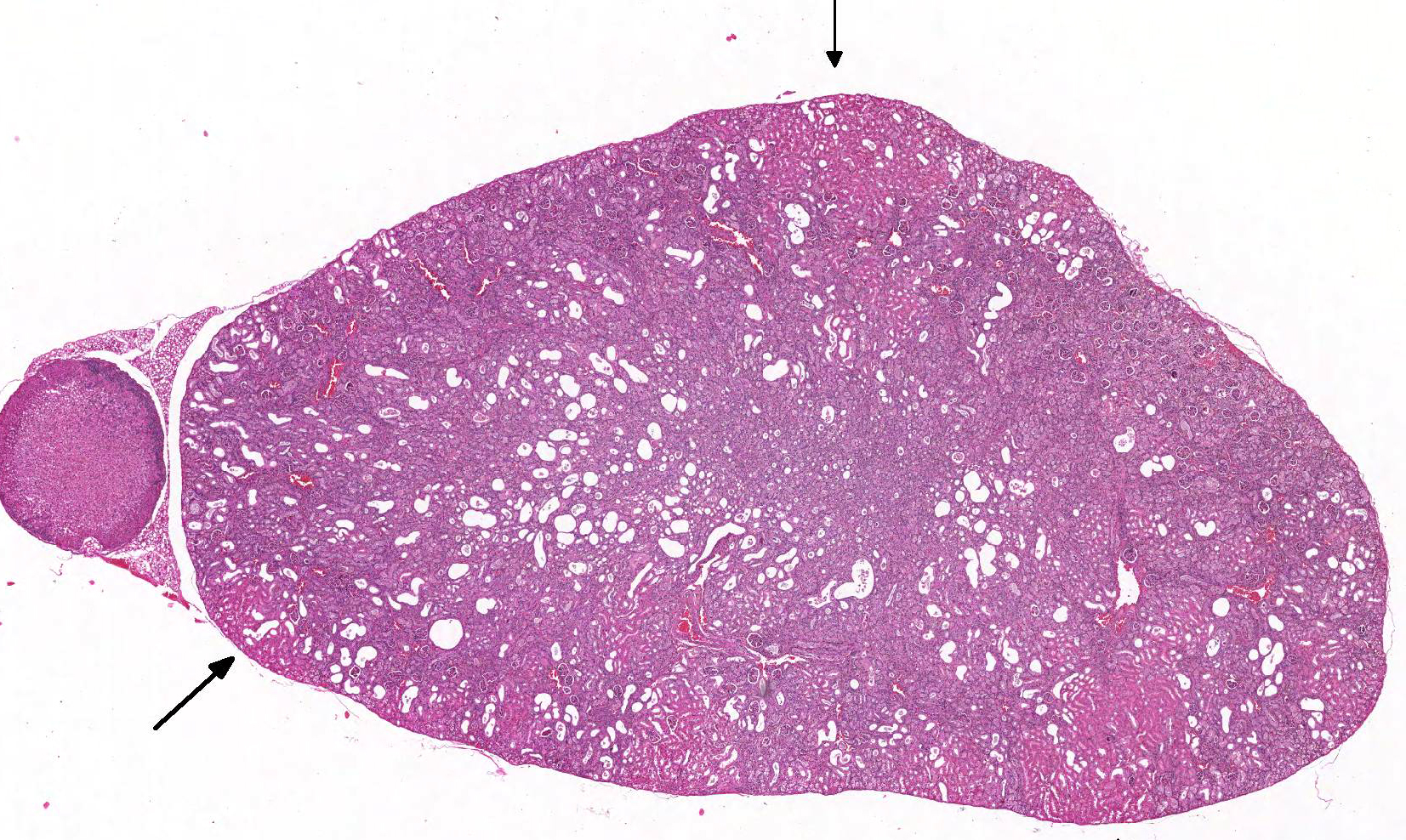

Gross Pathology: The kidneys were described as pale by the technician.

Laboratory results: None.

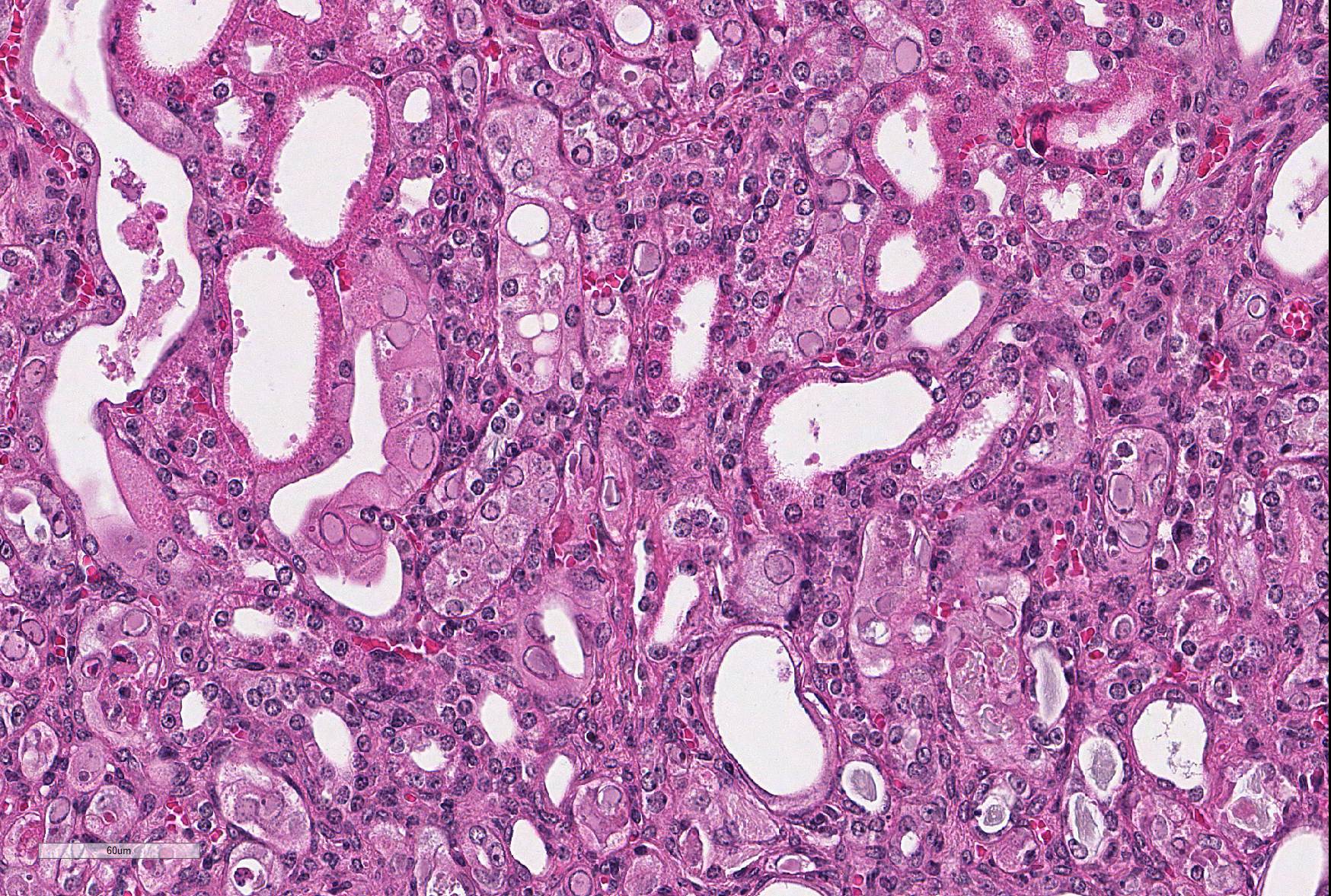

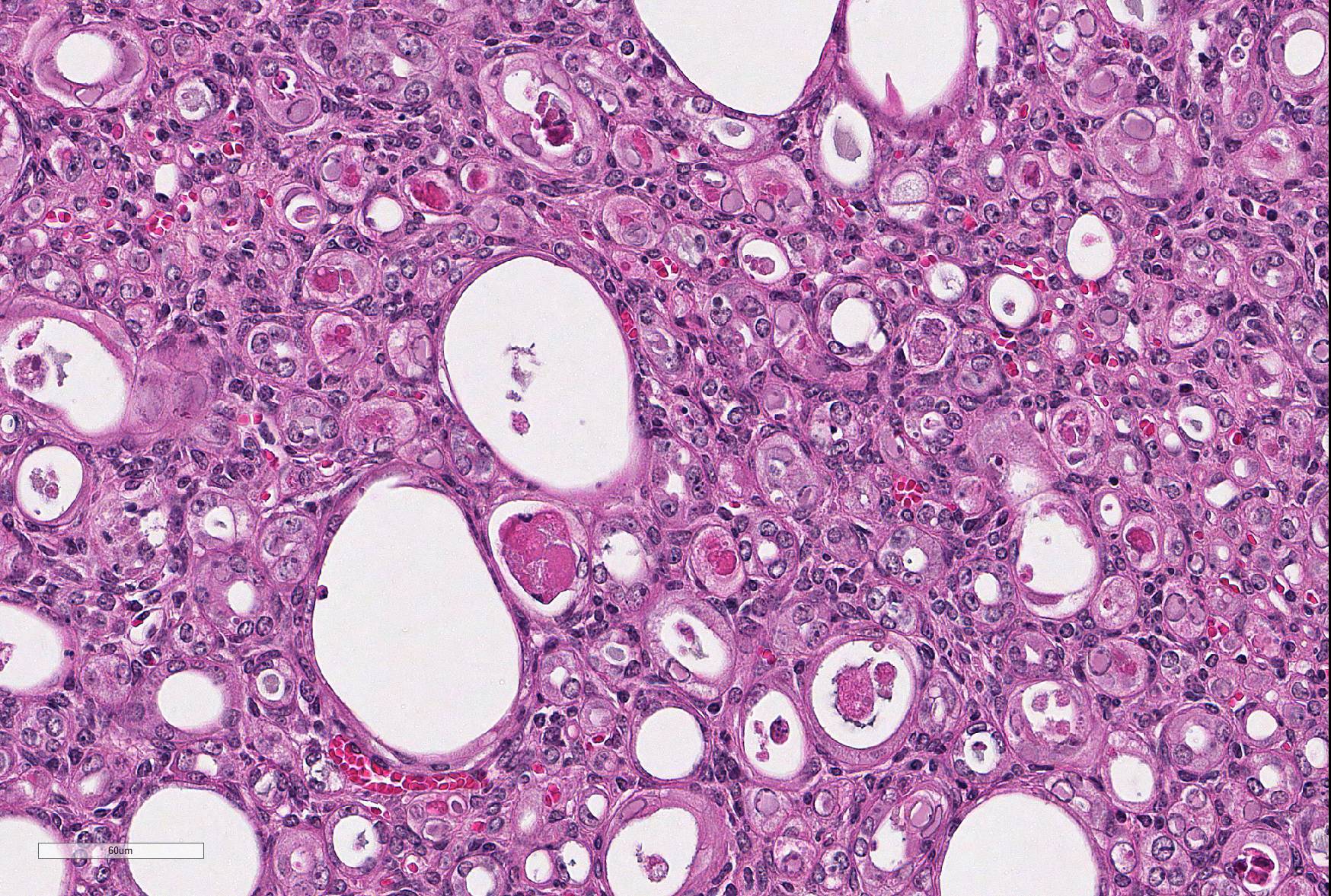

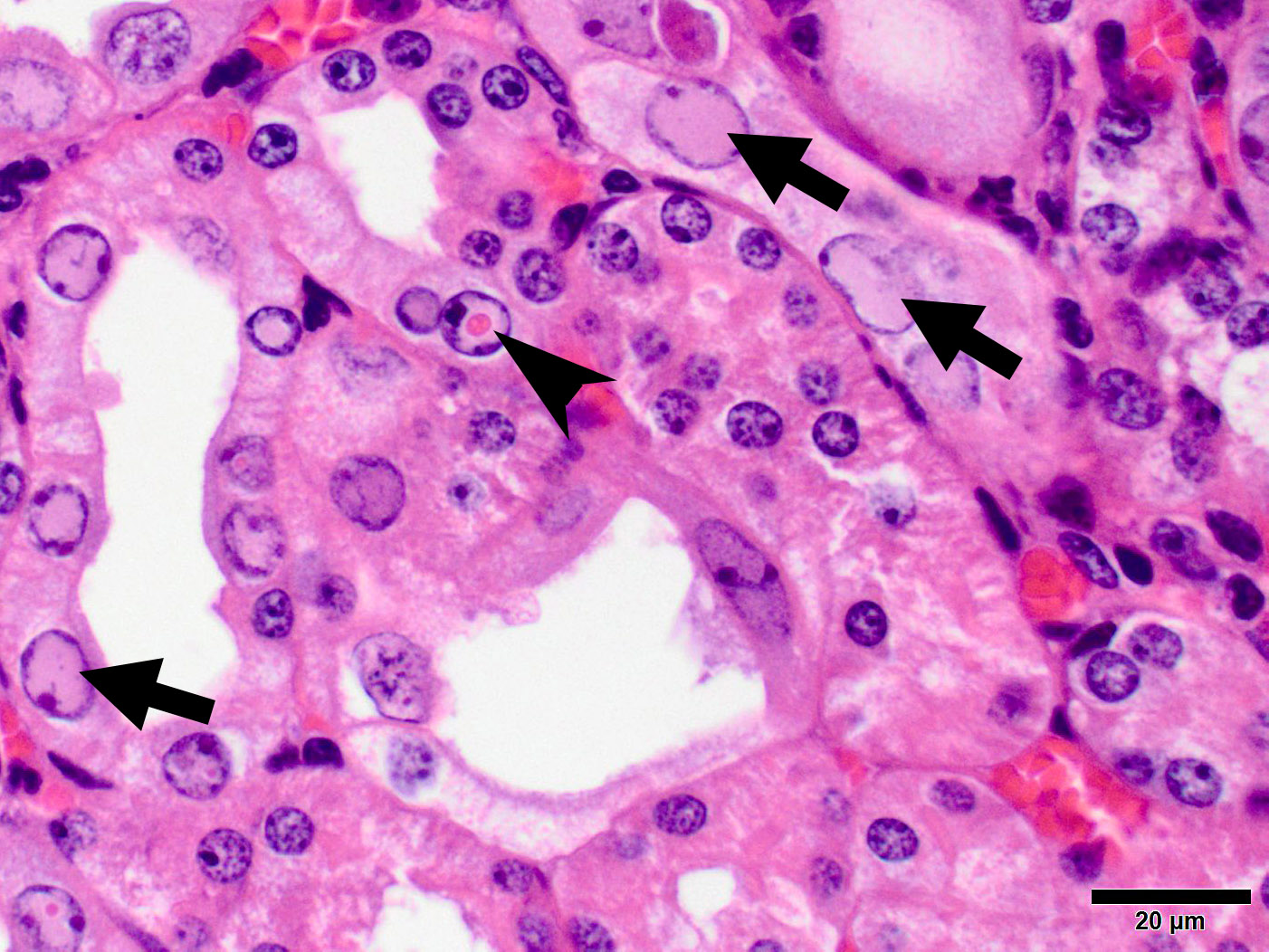

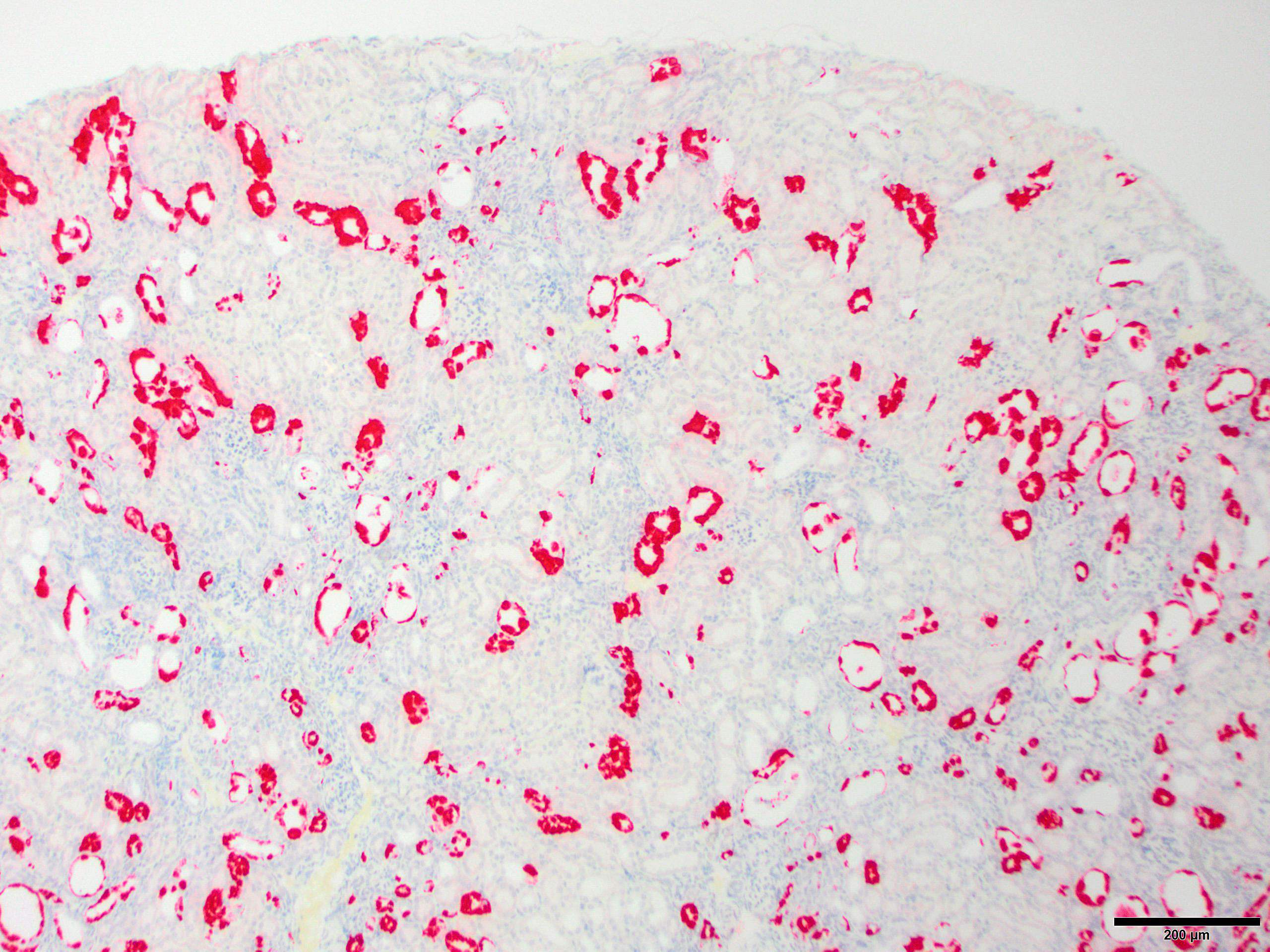

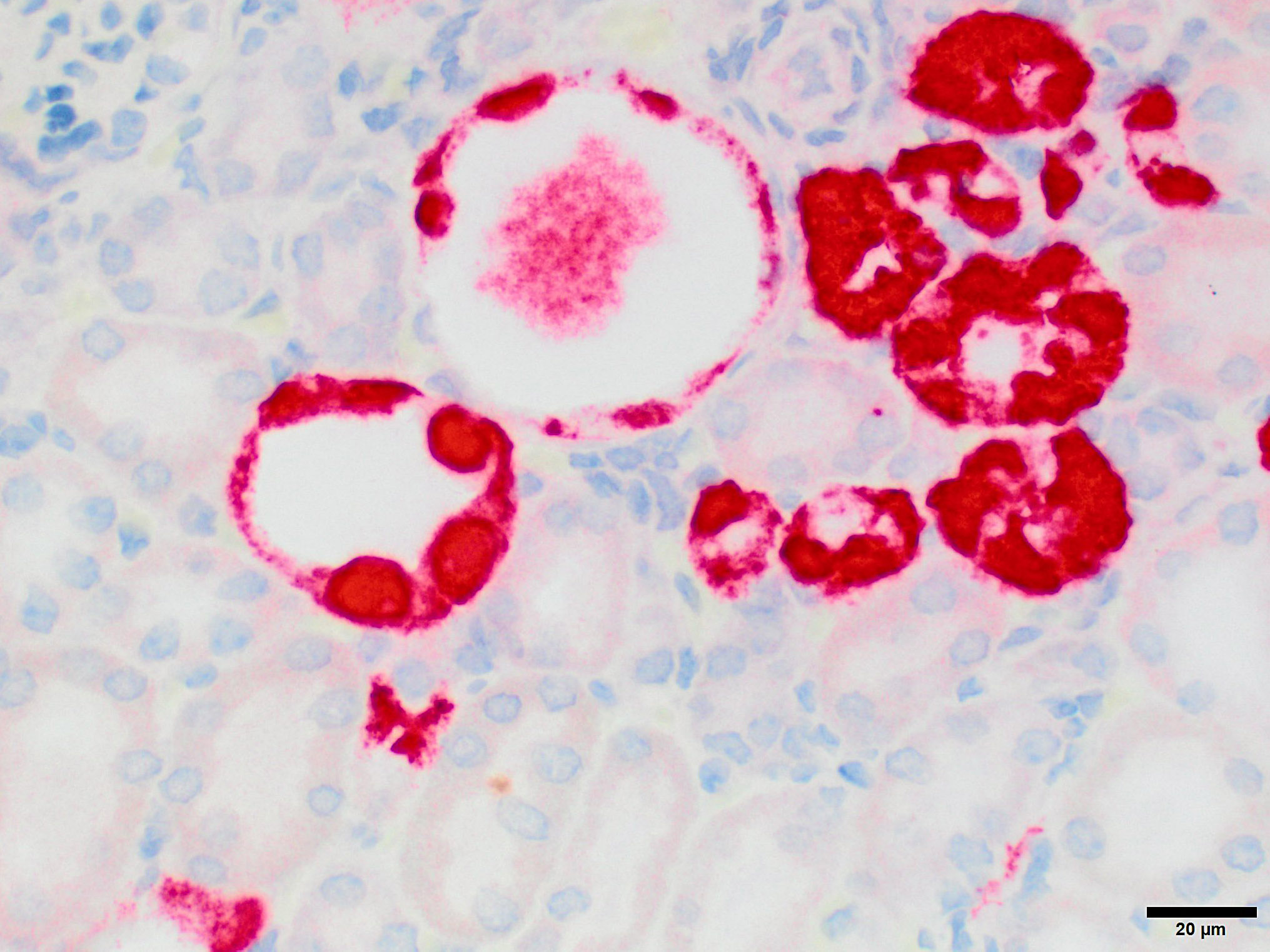

Microscopic Description: Kidney: The kidney appears reduced in size. The capsular surface is irregular and there is a marked reduction in the number of normal proximal convoluted tubules. Most of the cortex is occupied by small tubules lined by cells that stain more lightly than normal. Many of these cells have karyomegalic nuclei with chromatin margination and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies. Their cytoplasm is pale and contains granular eosinophilic material. Other degenerative changes seen in the pale tubules include lining by a reduced number of cells, flattening, loss and anisokaryosis and anisocytosis of lining cells and accumulation of intraluminal debris. There is multifocal mild to moderate tubular dilation and the dilated tubules show similar degenerative changes. There is mild multifocal interstitial fibrosis and scattered accumulation of granular brown material in tubular lining cells, and possibly in macrophages.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: Multifocal severe tubular degeneration and loss with karyomegalic and intranuclear inclusion bodies

Contributor’s Comment: Shortly after the publication of the first version of the results for this conference, the JPC was contacted by Dr. Sébastien Monette, who is part of a multi-institutional research group that has been investigating this condition over a number of years. (Much of the discussion below is the result of personal communications from Dr. Monette and Dr. Ben Roediger).

While milder lesions associated with renal tubular inclusions were previously reported in mice1,2, as discussed by the contributor, description of the severe form of murine inclusion body nephropathy (IBN), as seen in the present case, was first reported in 20174 as part of an article on aging changes in NOD scid gamma (NSG) female mice. The article described moderate to marked renal tubular degeneration and necrosis with two types of intranuclear inclusions within renal cortical and medullary tubular epithelial cells (numerous large pale inclusions filling the nucleus, and occasional small densely staining inclusions surrounded by a clear halo; as observed in this case - the presence of these two distinct types of inclusions may be of diagnostic value to pathologists encountering these lesion for the first time.) These lesions were associated with marked elevation of serum BUN and creatinine concentrations, and were determined to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the colony being studied. Renal samples were negative on PCR for mouse adenovirus 1 and 2, murine cytomegalovirus, and murine polyomavirus. TEM performed on 2 cases failed to identify viral particles (similar to the results obtained on this case at the JPC following the conference).

Unbiased viral metagenomic analysis of affected kidney samples lead to the discovery of a novel viral sequence, and this virus was shown to be the cause of murine IBN in a series of observational and experimental transmission studies, performed by scientists in multiple organizations, and described in the paper by Roediger et al3, published a month after the conference. These findings have finally shed light on the elusive etiology of a lesion that has puzzled pathologists for decades. The etiology of the lesion, an atypical parvovirus, was shown to cause naturally occurring morbidity, mortality, and marked lesions in highly immunodeficient mice such as NSG and Rag1 knockout mice, and subclinical infection and mild lesions in immuno-competent mice and athymic nude mice.

The novel parvovirus, termed "mouse kidney parvovirus" (MKPV), is highly divergent from the known mouse parvoviruses, mouse parvovirus (MPV) and the minute virus of mice (MVM) and is not detected by serology and PCR for these viruses. Based on analysis of its sequence, this virus apparently belongs to a new genus with the proposed name chapparvovirus, recently found in bats, wild rats, and pigs, but without disease association. In mice, it causes unusual pathology compared to typical parvoviruses. Unlike most parvoviruses which tend to require actively dividing cells to replicate (intestinal crypts, hematopoietic cells, external germinal cells of the developing cerebellum) this virus replicates predominantly in renal tubular cells, an unusual target for a virus of this family. The infection is chronic, and in immunodeficient strains leads to progressive tubular injury and loss, with interstitial fibrosis in advanced stages, over a period of months.

Attempts at isolating the virus in several cell lines have failed; therefore a pure inoculum could not be obtained and Koch's postulate could not be fulfilled. The causal relationship between MKPV and IBN was demonstrate in this article by a sum of evidence3, including:

- MKPV virus was detected by PCR from kidney tissues in cases of IBN and never detected in the kidneys of normal mice.

- By in situ hybridization (ISH) staining for viral RNA, the virus was detected in kidneys with IBN but not in normal kidneys. Importantly, within affected kidneys the staining was localized to abnormal tubules with karyomegaly and degenerative changes but not present in normal tubules, suggesting that the viruses causes the lesions and is not simply a bystander.

- Viral load in urine and kidney, as measured by quantitative PCR, showed concordance with clinical progression, histopathologic severity of lesions, and serum BUN concentration.

The investigators have found evidence of this virus in laboratory mice in multiple research facilities in the US and Australia, in samples collected over a period of eleven years. Material from this particular case was sent to Dr. Monette and evaluated via RNA ISH and was strongly positive for this virus, with a staining pattern as previously described, adding evidence that this pathogen is likely widespread throughout the world.

While the virus has been identified in laboratory mice in several facilities, the prevalence of infection by MKPV within these facilities was not clear, as detection of cases was primarily based on histo-pathological observation of the lesions followed by confirmation by PCR and ISH. Because immunocompetent mice develop much milder lesions that may be missed, and no clinical signs, determination of the true prevalence will require surveys by PCR or serology. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that MKPV may have significant negative impacts on research performed with mouse models, as it can cause unexpected morbidity and mortality in highly immunodeficient strains, but also because it may have subtle, but potentially significant effect on the outcome of research performed in all mice, including immunocompetent strains. Further research is ongoing to determine the impact on this virus on biomedical research that relies on mouse models.

JPC Diagnosis: Kidney, tubular epithelium: Karyomegaly, with numerous eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions.

Conference Comment: Shortly after the publication of the first version of the results for this conference, the JPC was contacted by Dr. Sébastien Monette, who is part of a multi-institutional research group that has been investigating this condition over a number of years. (Much of the discussion below is the result of personal communications from Dr. Monette and Dr. Ben Roediger).

While milder lesions associated with renal tubular inclusions were previously reported in mice1,2, as discussed by the contributor, description of the severe form of murine inclusion body nephropathy (IBN), as seen in the present case, was first reported in 20174 as part of an article on aging changes in NOD scid gamma (NSG) female mice. The article described moderate to marked renal tubular degeneration and necrosis with two types of intranuclear inclusions within renal cortical and medullary tubular epithelial cells (numerous large pale inclusions filling the nucleus, and occasional small densely staining inclusions surrounded by a clear halo; as observed in this case). These lesions were associated with marked elevation of serum BUN and creatinine concentrations, and were determined to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the colony being studied. Renal samples were negative on PCR for mouse adenovirus 1 and 2, murine cytomegalovirus, and murine polyomavirus. TEM performed on 2 cases failed to identify viral particles (similar to the results obtained on this case at the JPC following the conference).

Unbiased viral metagenomic analysis of affected kidneys samples lead to the discovery of a novel viral sequence, and this virus was shown to be the cause of murine IBN in a series of observational and experimental transmission studies, performed by scientists in multiple organizations, and described in the paper by Roediger et al3, published a month after the conference. These findings have finally shed light on the elusive etiology of a lesion that has puzzled pathologists for decades. The etiology of the lesion, an atypical parvovirus, was shown to cause naturally occurring morbidity, mortality, and marked lesions in highly immunodeficient mice such as NSG and Rag1 knockout mice, and subclinical infection and mild lesions in immunocompetent mice and athymic nude mice.

The novel parvovirus, termed “mouse kidney parvovirus” (MKPV), is highly divergent from the known mouse parvoviruses, mouse parvovirus (MPV) and the minute virus of mice (MVM) and is not detected by serology and PCR for these viruses. Based on analysis of its sequence, this virus apparently belongs to a new genus with the proposed name chapparvovirus, recently found in bats, wild rats, and pigs, but without disease association. In mice, it causes unusual pathology compared to typical parvoviruses. Unlike most parvoviruses which tend to require actively dividing cells to replicate (intestinal crypts, hematopoietic cells, external germinal cells of the developing cerebellum) this virus replicates predominantly in renal tubular cells, an unusual target for a virus of this family.. The infection is chronic, and in immunodeficient strains leads to progressive tubular injury and loss, with interstitial fibrosis in advanced stages, over a period of months.

Attempts at isolating the virus in several cell lines have failed; therefore a pure inoculum could not be obtained and Koch’s postulate could not be fulfilled. The causal relationship between MKPV and IBN was demonstrate in this article by a sum of evidence3, including:

- MKPV virus was detected by PCR from kidney tissues in cases of IBN and never detected in the kidneys of normal mice.

- By in situ hybridization (ISH) staining for viral RNA, the virus was detected in kidneys with IBN but not in normal kidneys. Importantly, within affected kidneys the staining was localized to abnormal tubules with karyomegaly and degenerative changes but not present in normal tubules, suggesting that that the viruses causes the lesions and is not simply a bystander.

- Viral load in urine and kidney, as measured by quantitative PCR, showed concordance with clinical progression, histopathologic severity of lesions, and serum BUN concentration.

The investigators have found evidence of this virus in laboratory mice in multiple research facilities in the US and Australia, in samples collected over a period of eleven years. Material from this particular case was sent to Dr. Monette and evaluated via RNA ISH and was strongly positive for this virus, with a staining pattern as previously described, adding evidence that this pathogen is likely widespread throughout the world.

While the virus has been identified in laboratory mice in several facilities, the prevalence of infection by MKPV within these facilities was not clear, as detection of cases was primarily based on histopathological observation of the lesions followed by confirmation by PCR and ISH. Because immunocompetent mice develop much milder lesions that may be missed, and no clinical signs, determination of the true prevalence will require surveys by PCR or serology. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that MKPV may have significant negative impacts on research performed with mouse models, as it can cause unexpected morbidity and mortality in highly immunodeficient strains, but also because it may have subtle, but potentially significant effect on the outcome of research performed in all mice, including immunocompetent strains. Further research is ongoing to determine the impact on this virus on biomedical research that relies on mouse models.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Resources,

Weizmann Institute of Science

Rehovot 76100, Israel

http://www.weizmann.ac.il/vet/

References:

- Baze WB, Steinbach TJ, Fleetwood ML, Blanchard TW, Barnhart KF, McArthur MJ. Karyomegaly and intranuclear inclusions in the renal tubules of sentinel ICR mice (mus musculus). Comp Med. 2006; 56:435-8.

- McInnes E, et al. Intranuclear Inclusions in Renal Tubular Epithelium in Immunodeficient Mice Stain with Antibodies for Bovine Papillomavirus Type 1 L1 Protein. Vet. Sci. 2015; 2: 84-96

- Roediger B, Lee Q, Tikoo S, Cobbin JCA, Henderson JM, Jormakka M, O’Rourke MB, Padula MP, Pinello N, Henry Marisa, Wynne M, Santagostino SF, Brayton CF, Rasmussen L, Lisowski L, Tay SS, Harris DC, Bertram JF, Dowling JP, Bertolino P, Lai JH, Wu W, Bachovchin WW, Wong JJL, Gorrel MD, Shaban B, Holmes EC, Jolly CJ, Monette S, Weninger W. An atypical parvovirus drives chronic tubulointerstitial nephropathy and kidney fibrosis. Cell; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.013

- Santagostino SF, Arbona RJR, Nashat MA, White JR, Monette S. Pathology of aging in NOD scid gamma female mice. Vet Pathol 2017; 54(5): 855-869.