CASE III:

Signalment:

12-year-old female Dutch Warmblood horse (Equus caballus)

History:

The mare presented in late pregnancy with a preliminarily diagnosed of nocardioform placentitis and was treated with antibiotics, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, and altrenogest for two weeks. She foaled on day 325 of gestation and fetal membranes were expelled 15 minutes post-partum.

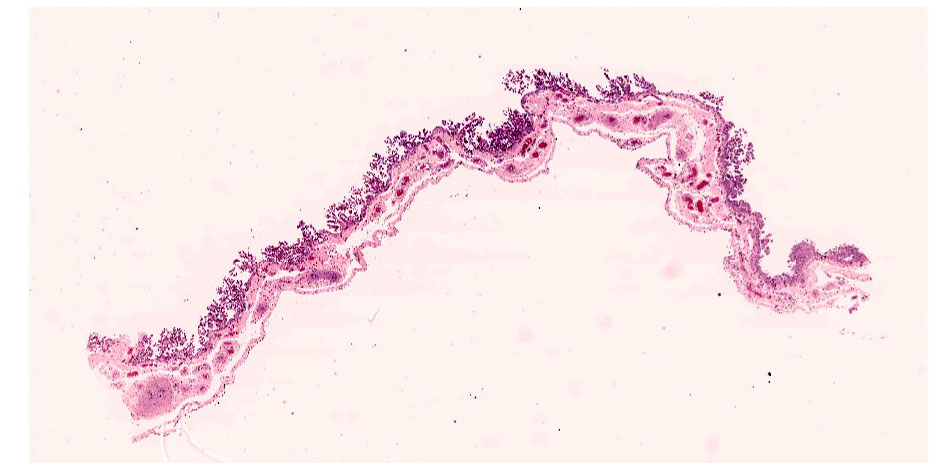

Gross Pathology:

The chorionic surface had a large avillous region, extending from the base of the pregnant horn to the cervical star. Approximately 50% of the entire chorionic surface was coated by tan-brown, opaque, viscous exudate extending to the cervical star. The amnion had diffuse mild opacity and edema. The chorioallantois weighed 3.8kg and the umbilical cord plus allantoamnion weighed 2.5kg. The total length of the umbilical cord is 80.5cm; with the total length of the amniotic segment being 45.4cm and the total length of the allantoic segment being 35.1cm.

Laboratory Results:

Aerobic culture of fresh chorioallantosis yielded moderate growth of bacteria in the Mycobacterium smegmatis group. 16S PCR sequencing of this isolate identified Mycobacterium goodii.

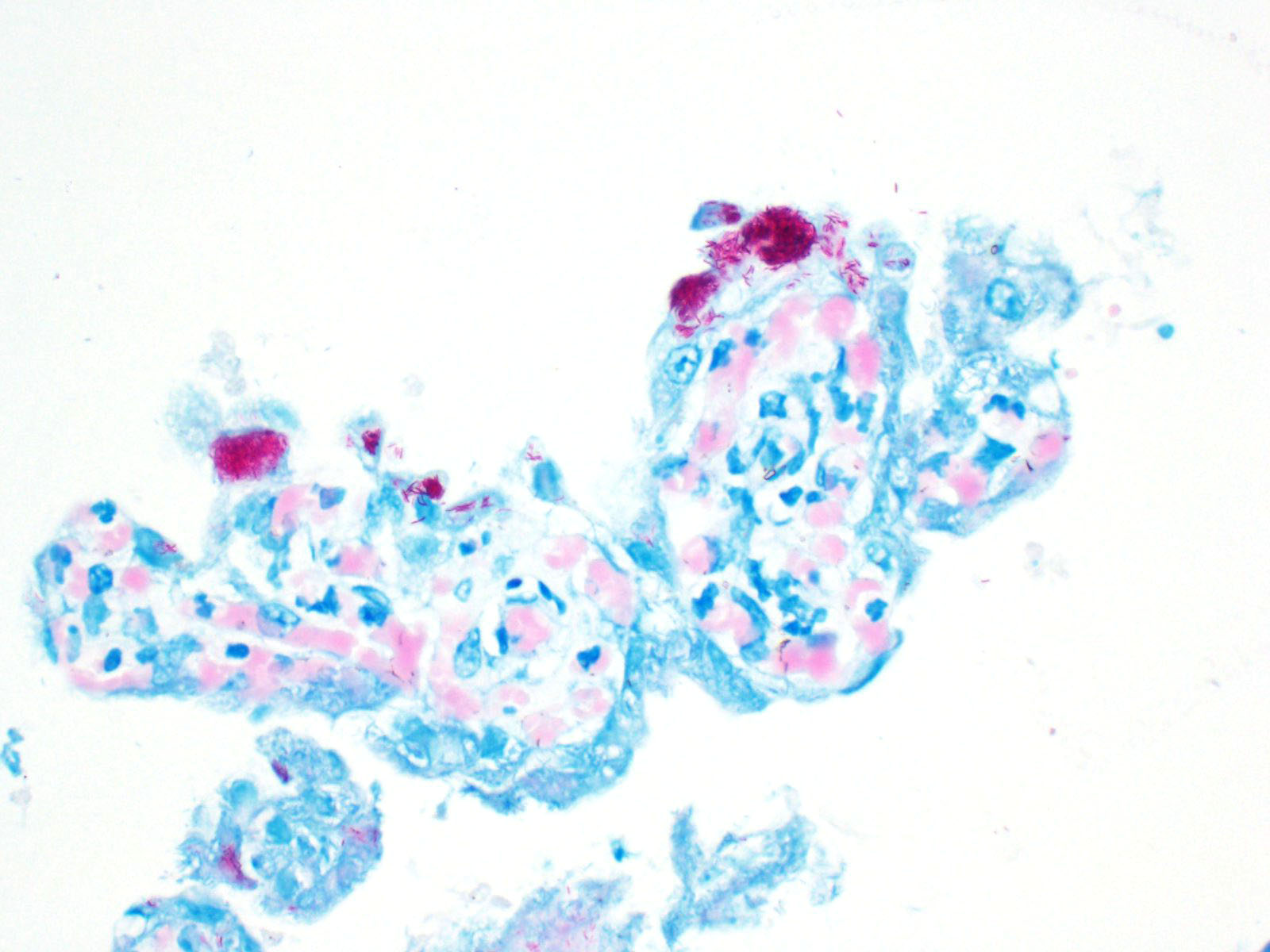

Microscopic Description:

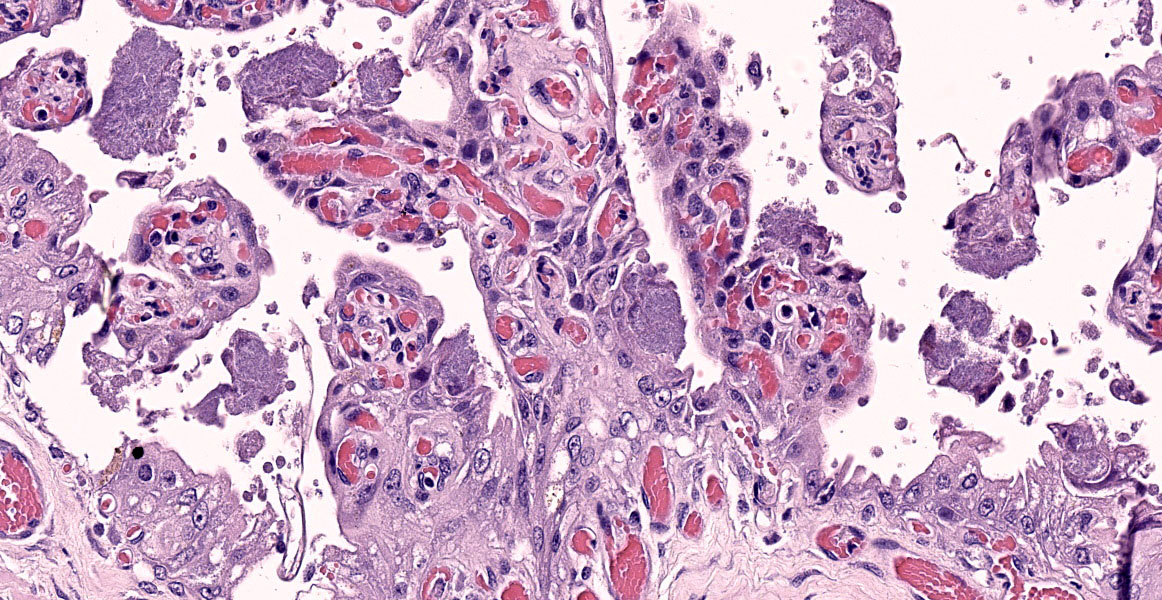

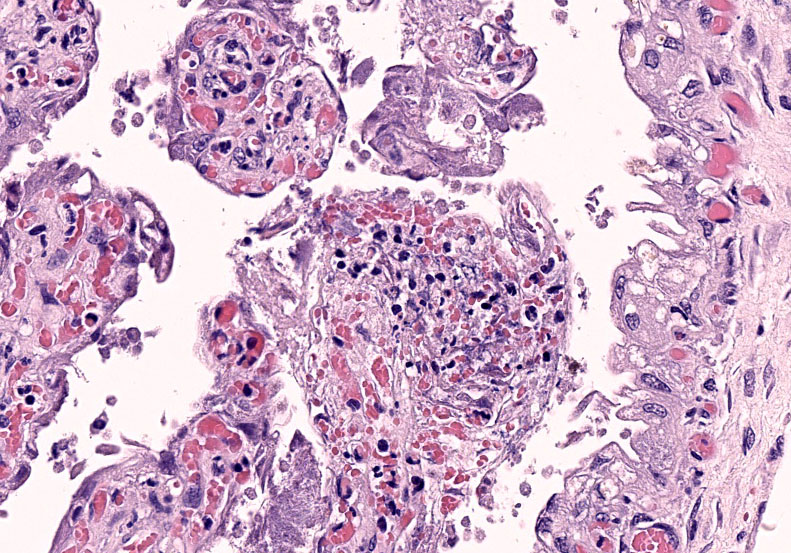

Chorioallantois (placenta): Subgrossly, large mesoderm vessels in the chorionic plate have hyperplastic smooth muscle and are congested. The chorion has progressive loss, thickening, fusion and de-arborization of microcotyledon villous projections and concurrent thickening of the trophoblastic epithelium.

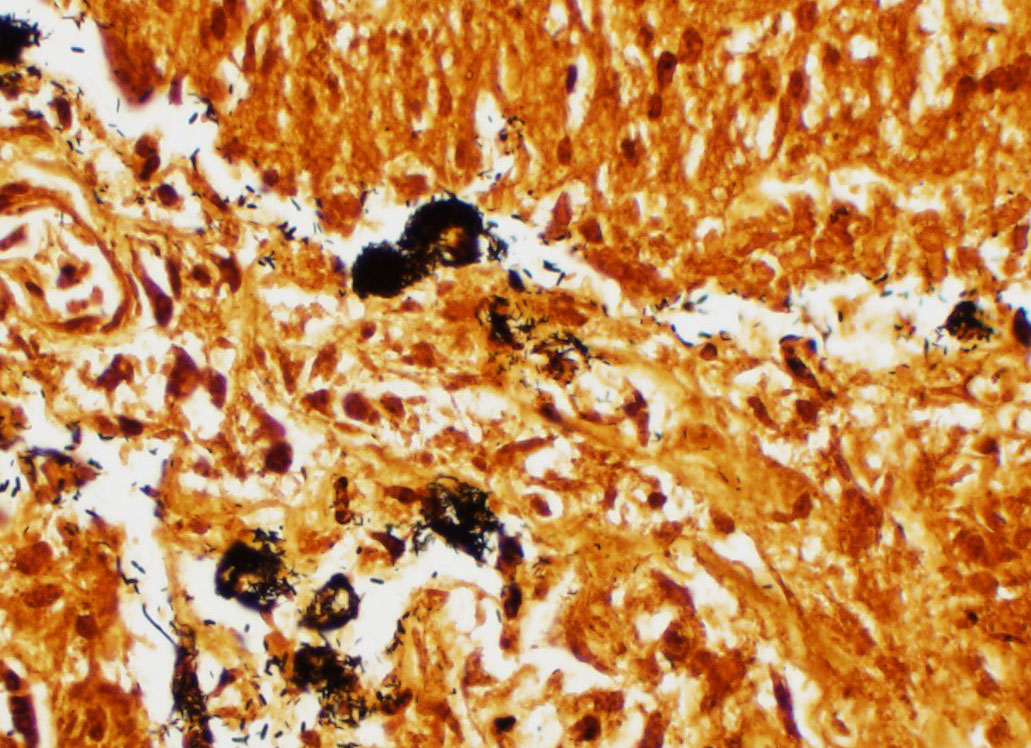

Vasculature of chorionic villi have obscured endothelium with severe marginization and perivascular cuffing by large numbers of neutrophils. The thickened sections of chorionic epithelium are composed of multilayered ballooned trophoblasts and syntrophoblasts packed with intracytoplasmic gram-positive, variably acid-fast positive, beaded bacilli. The chorionic surface has variable amounts of detached amalgamated degenerate trophoblasts with similar intracellular organisms. Chorionic connective tissues contain low numbers of infiltrating plasma cells, macrophages and neutrophils. Allantoic epithelium is multifocally eroded.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Chorioplacentitis, degenerative, neutrophilic to lymphoplasmacytic, regionally extensive, chronic, severe, with intralesional intratrophoblastic, acid-fast bacilli, chorioallantois.

Contributor's Comment:

The focal distribution of equine nocardioform placentitis usually infects the chorionic surface of the body or horns sparing the cervical star. In this case, brown viscous exudate coating the chorionic lesion was characteristic of that observed in nocardioform placentitis that has been attributed to Crossiella equi, Amycolatopsis, and Streptomyces spp. and others.3,4,8,13 Histologically, strongly acid-fast positive (Fite's method) intratrophoblastic bacilli were continuous with the body of the chorioallantois but had highest density in the cervical star, suggesting an ascending infection. Aerobic culture yielded moderate growth of bacteria in the Mycobacterium smegmatis related group and 16S sequencing more specifically identified Mycobacterium goodii as the etiology.

In horses mycobacterial placentitis has been attributed to various subspecies of Mycobacterium avium, specifically hominissuis and those in Runyon group IV.5,7 Mycobacterium smegmatis has been implicated in experimental induction of mastitis and granulomatous mastitis in sheep and dairy cattle, systemic disease in immunocompromised canids and peritonitis in goldfish.13 M. smegmatis has also caused nosocomial infections associated with post-surgical breast implants and osteomyelitis, lymphadenitis, cellulitis, and aspiration pneumonia in humans.1,4

Taxonomic studies of Mycobacterium smegmatis have elucidated three subgroups with emerging clinical significance, one being Mycobacterium goodii.1,4 This subgroup has been reported, in human medical literature, to have been cultured and implicated in the development of post-traumatic and/or post-surgical wound infections following surgical implantation of medical devices.3,4,9 To the knowledge of the contributor, this is the first case of mycobacterial placentitis in an equid attributed to Mycobacterium goodii.

Contributing Institution:

University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Comparative, Diagnostic, and Population Medicine https://cdpm.vetmed.ufl.edu/

JPC Diagnosis:

Placenta, chorioallantois: Placentitis, necro-tizing and neutrophilic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with numerous intratrophoblastic and extracellular bacilli.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise overview of etiologies associated with nocardioform placentitis and the emergence of Mycobacteria goodie as not only a cause of nosocomial infections in humans but also a cause of mycobacterial placentitis in mares.

Mycobacterium goodii is a Gram-positive acid fast bacillus classified as a nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) that exhibits rapid growth (2-4 days) on most media, including blood, chocolate, trypticase soy, Middlebrook 7H10 or 7H11, and Lowenstein-Jensen agars; however, gene sequencing is required for differentiation from other rapidly growing NTM.12 In addition to M. goodii, other rapidly growing mycobacterial species include those in the M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, and M. chelonae-abscessus groups as well as other species such as M. phlei and M. thermoresistible. Rapidly growing mycobacterial species are ubiquitous in the environment and can be found in soil, dust, and drinking water.2, 11 As noted by the contributor, M. goodii is closely related to M. smegmatis, an agent commonly associated with nosocomial infections.12

In 1999, Brown et al. reclassified M. smegmatis into three species (M. smegmatis sensu stricto, M. wolinskyi, and M. goodii) based on genetic sequence and antimicrobial resistance. Each species may be identified with up 90% accuracy based on its sensitivity to tobramycin, with M. smegmatis sensu stricto being most susceptible, followed by M. goodii with intermediate susceptibility, and M. wolinskyi being resistant.2

As previously noted, M. goodii is commonly associated with nosocomial infections in human healthcare settings following invasive procedures. Implantations such as prosthetic joints and cardiac pocket devices such as pacemakers and automated implantable cardiac defibrillators are most commonly affected.12

Treatment typically entails a complex combination of implant removal, surgical debridement, and prolonged appropriate antibiotic therapy (up to 12 months). Many cases are initially treated empirically with clarithromycin and rifampin, both of which M. goodii is inherently resistant due to its overexpression of the Wag31 gene and presence of the erm gene. Wag31 reduces M. goodii's permeability to lipophilic medications such as rifampin by increasing the thickness of the peptidoglycan layer while the erm gene alters the ribosomal binding site targeted by macrolides such as clarithromycin. The most effective medications for the treatment of M. goodii in humans are sulfamethoxazole /trimethroprim and ethambutal. However, allergies and renal toxicity often limit the use of sulfamethoxazole/trimethroprim, necessitating the use of alternatives such as doxycycline and ciprofloxacin or a combination of amikacin and meropenem for more serious infections.12

Infection caused by rapidly growing mycobacterial species have also been reported in cats and less commonly in dogs. These infections most commonly result in panniculitis and are often preceded by some form of trauma, such as bite wounds, penetrating foreign bodies, or surgical manipulation. These lesions vary from single to multiple, firm, often painless, subcutaneous nodules with multiple draining tracts to subcutaneous abscesses. Dogs are often affected in regions associated with bite wounds or subcutaneous injections, such as the dorsum, flank, dorsal neck, and shoulder, in addition to surgical or intravenous catheterization sites. The inguinal region is most commonly affected location in cats.2

In mares, placentitis is a common cause of pregnancy loss, which occurs due to inhibition of nutrient and fetal waste transfer across the placenta. As previously noted by the contributor, some cases equine placentitis may be categorized as ?nocardioform? or ?mucoid?, implying a nonascending placentitis. In these cases, the cervical star region of the chorioallantois is spared while bacterial foci are distributed to the body and/or horns of the chorioallantois. In contrast, ascending placentitis occurs as the result of pathogens crossing the cervical barrier, classically resulting in inflammation, thickening, and separation of the chorioallantois at the region on the cervical os (i.e. cervical star). Sreptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus is the most common bacterial isolate associated with ascending placentitis, followed by Escherichia coli, Pesudomonas spp., and Klebsiella spp. As previously discussed by the contributor, etiologies associated wtih nocardioform placentitis include common soil-borne bacteria such as Crossiella equi, Amycolatopsis sp., Streptomyces sp., and Cellulosimicrobium cellulans.6

A similar case of an equine abortion is reported in a 2014 report by Johnson et al.6, which describes a case of mycobacterial placentitis with intratrophoblastic acid-fast bacteria in the cervical star chorion without villous necrosis, inflammation, or hyperplasia of trophoblasts. In the case of the 2014 report, culture revealed a pure growth of Mycobacterium Runyon IV, which are comprised of fast-growing, saprophytic, acid fast, nontuberculous bacilli, which encompasses all mycobacteria outside the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, including M. goodii. Sequence analysis using the 16S ribosomal RNA gene and the rpoβ gene found the isolate contained a 5% difference in the rpoβ gene compared to known species at the time, indicating a novel species. Five similar cases of mycobacterial abortion reported in Kentucky thoroughbred mares between 2002 and 2006 were also attributed to an unknown species of Mycobacterium.6 Considering the present case is the first identified case of M. goodii placentitis, a retrospective analysis of tissue samples from the previously described cases may be warranted.

Although Mycobacteria spp. are rarely associated with placentitis and abortion, mycobacteriosis should be considered in cases where more common bacteria are not isolated. Furthermore, use of acid-fast stains should be considered in cases of equine placentas exhibiting atypical placentitis lesions.6

Conference participants discussed the absence of microcotyledons at the lateral aspect of the tissue section and its significance. Although the exact location of placenta was not specified, the absence of microcotyledons indicates the tissue section most likely includes a portion of the cervical star. As noted in the contributor's comment, thickening of the cervical star is consistent with an ascending infection.

Finally, the moderator and the majority of attendees were of the opinion that this case is inconsistent with nocardioform placentitis. Although the presence of brown exudate is a feature of nocardioform placentitis, the hyperplastic chorioallantois in the region interpreted to be the cervical star is more consistent with an ascending infection.

References:

1. Brown BA, Springer B, Steingrube VA, et al. Mycobacterium wolinskyi sp. nov. and Mycobacterium goodii sp. nov., two new rapidly growing species related to Mycobacterium smegmatis and associated with human wound infections: a cooperative study from the International Working Group on Mycobacterial Taxonomy. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49 Pt 4:1493-1511.

2. Bryden SL, Burrows AK, O'hara AJ. Mycobacterium goodii infection in a dog with concurrent hyperadrenocorticism. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15(5):331-338.

3. Erol E, Williams NM, Sells SF, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Crossiella equi and Amycolatopsis species causing nocardioform placentitis in horses. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24(6):1158-1161.

4. Ferguson, Dayna Devon, et al. "Mycobacterium goodii infections associated with surgical implants at Colorado hospital." Emerging infectious diseases 10.10 (2004): 1868.

5. Friedman ND, Sexton DJ. Bursitis due to Mycobacterium goodii, a recently described, rapidly growing mycobacterium. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(1):404-405.

6. Johnson AK, Roberts JF, Hagan A, et al. Infection of an equine placenta with a novel mycobacterial species leading to abortion. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24(4):785-790.

7. Kinoshita Y, Takechi M, Uchida-Fujii E, Miyazawa K, Nukada T, Niwa H. Ten cases of Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis infections linked to equine abortions in Japan, 2018-2019. Vet Med Sci. 2021;7(3):621-625.

8. Maxie, Grant. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Volume

3. Vol. 3. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015.

9. Newton JA Jr, Weiss PJ, Bowler WA, Oldfield EC 3rd. Soft-tissue infection due to Mycobacterium smegmatis: report of two cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(4):531-533.

10. Pavlik, I., et al. "Mycobacterial infections in horses: a review of the literature."

Veterinarni Medicina 49.11 (2004): 427.

11. Pfeuffer-Jovic E, Heyckendorf J, Reischl U, et al. Pulmonary vasculitis due to infection with Mycobacterium goodii: A case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:178-180.

12. Salas NM, Klein N. Mycobacterium goodii: An Emerging Nosocomial Pathogen: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract (Baltim Md). 2017;25(2):62-65.

13. Talaat AM, Trucksis M, Kane AS, Reimschuessel R. Pathogenicity of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium smegmatis to goldfish, Carassius auratus. Vet Microbiol. 1999;66(2):151-164.

14. Wallace RJ Jr, Nash DR, Tsukamura M, Blacklock ZM, Silcox VA. Human disease due to Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Infect Dis. 1988;158(1):52-59.