Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

While the genetic composition of the coronavirus affects the degree of virulence, the severity of disease is also directly linked to the genetic background of the affected animal. The literature describes a genetic predisposition which suggests that certain subsets of cats are at higher risk for clinical disease than other populations2. Evaluation of a large cohort of different cat breeds noted that Birman, Ragdoll, Bengal, Rex, Abyssinian, and Himalayan breeds may be predisposed1,8. Similar findings have been noted in cheetah populations which are at increased risk for FIP infection(3,6,8).

Initial FIP viral replication occurs in the tonsils or intestinal tract, followed by incorporation into histiocytes and transmission to the regional lymph nodes where the virions replicate within macrophages, thereby disseminating the virus throughout the body. The severity of FIPV infection, once the virus is systemic, is determined by the hosts immune response. A strong cell-mediated immune response can clear the infection and clinical feline infectious peritonitis will not develop; however, in cats with a poor cell-mediated immune response, antibodies develop which may facilitate macrophage uptake of virus and exacerbate the course of disease. Furthermore, the absence of CMI antigen-antibody complexes results in a type 3 hypersensitivity reaction with associated vasculitis and effusion into body cavities, to include the ocular chambers(1,2,6).

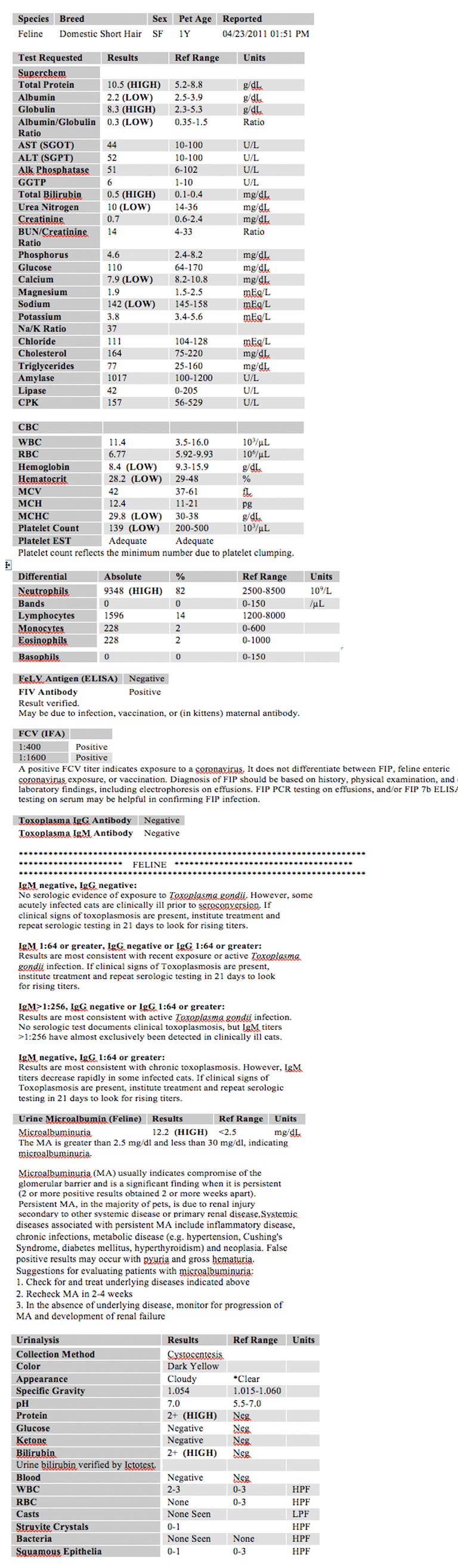

While a variety of diagnostic modalities have been suggested, there is no gold standard for FIP diagnosis other than histopathology with accompanying immunohistochemistry3. However, CBC, blood chemistry, and serology can be highly suggestive of FIP infection and clinically ill cats with FIP may demonstrate the following abnormalities:

- Normocytic, normochromic, non-regenerative anemia

- Neutrophilic leukocytosis with lymphopenia, eosinopenia and monocytosis

- Hyperproteinemia with hyperglobulinemia

- Decreased Albumin:Globulin ratio (increased α2-, β- and γ-globulin concentrations)

Ocular pathology with panuveitis is a common finding with associated iridial changes in iris color, dyscoria or anisocoria secondary to iridocyclitis followed by a sudden loss of vision and clinically observable hyphema. Keratic precipitates colloquially known as -Ç-ÿmutton fat deposits on the ventral corneal endothelium are reported. On ophthalmoscopic examination, chorioretinitis, fluffy perivascular cuffing (representing retinal vasculitis), dull perivascular puffy areas (pyogranulomatous chorio-retinitis), linear retinal detachment and fluid blistering under the retina may be observed and these findings mirror those seen microscopically(1).

As a result of the unique anatomical and functional nature of the eye, pathology within one structure can have significant bystander effects on other tissues resulting in progressive destruction and a continuum of pathology from potential inflammation of one region, eventually progressing to complete destruction of the globe. Due to the probable type 3 hypersensitivity associated with the pathogenesis of FIPV in this case, with vasculitis concentrated in the uvea and the sclera, and the resultant effusion into the ocular chambers, the preferential morphological diagnosis defers to the vasculitis as the primary modifier and then identification of each ocular structure in turn affected by the progressive inflammatory process.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The diffuse uveitis associated with FIP is likely an immune-mediated reaction and, more specifically, a Type III hypersensitivity reaction. Type III hypersensitivity reactions result from the deposition of antigen-antibody complexes in vascular walls, serosa, and glomeruli and result in localized vasculitis from the activation of complement, the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes, and subsequent damage from the liberation of free radicals and lysozymes. As the leukocyte adhesion cascade becomes activated, macrophages bind to the endothelium and release proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in an acute inflammatory response. Type III hypersensitivity occurs when there is a greater proportion of antigen to antibody, resulting in the formation of medium-sized immune complexes that do not fix complement and are not cleared from the circulation because macrophages are unable to bind them(7).

Interestingly, FIP-induced ocular lesions are always bilateral. Although FIP typically results in pyogranulomatous inflammation of multiple organs, the inflammatory picture in the eye is unique. The anterior chamber is usually affected by a neutrophilic exudate, while lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is present in the uvea and choroid(5). Also, in cats, there is no other known cause except FIP for the characteristic inflammation of the extra-ocular muscles combined with uveitis.

In this case, the drainage angle is open, which is to be expected in ocular FIP because the eye is one of the last organs to be infected in this disease, and the cat often dies of severe lesions elsewhere before there is time to develop glaucoma. There is also loss of the inner layers of the retina due to pressure necrosis from the exudate in the vitreous. The detachment of the retina is likely due to effusion in the choroid with leakage into the subretinal space, a process known as exudative retinal detachment(5). Also present are collagen strands on the anterior surface of the iris, which represent pre-iridal fibrovascular membrane (rubeosis iridis in humans) formation. Pre-iridal fibrovascular membranes are initially composed of polymerized fibrin, hemorrhage, and high protein exudate in the anterior chamber, and are common in acute and chronic ophthalmitis in cats. Pre-iridal membranes originate as endothelial buds from the anterior iridal stroma and mature into fibrovascular membranes that can result in hyphema or glaucoma due to leaky interendothelial junctions of the new vessels resulting in occlusion of the filtration angle or the pupillary opening. This layer of granulation tissue then matures in typical fashion. Pre-iridal fibrovascular membranes are often difficult to identify due to the heavy pigmentation of the iris, and the severe concurrent inflammation that can accompany this phenomenon(4).

References:

2. Chang H, de Groot RJ, Egberink HF and Rottier PJM: Feline infectious peritonitis: insights into feline coronavirus pathobiogenesis and epidemiology based on genetic analysis of the viral 3c gene. Journal of General Virology. 91, 415420, 2010

3. Diaz JV and Poma R: Diagnosis and clinical signs of feline infectious peritonitis in the central nervous system. Can Vet J. 50(10): 10911093, 2009

4. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Disease of the Immune System. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed., Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Elsevier; 2010:204-5.

5. Njaa BL, Wilcock BP. The Eye and ear. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD eds., Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed., St. Louis, MO:Elsevier Mosby; 2011:1208-1211, 1244.

6. Paltrinieri S, Grieco V, Comazzi S, Parodi MC: Laboratory profiles in cats with different pathological and immunohistochemical findings due to feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 3, 149159, 2001

7. Peiffer RL, Wilcock BP, Yin H. The Pathogenesis and Significance of Pre-iridal Fibrovascular Membrane in Domestic Animals. Vet Pathol. 1990; 27(1):41-5.

8. Pesteanu-Somogyi LD, Radzai C and Pressler BM: Prevalence of feline infectious peritonitis in specific cat breeds. J Feline Medicine and Surgery 8:1-5, 2006