Signalment:

At the referral center, the dog was again noted to be thin (BCS 2/9) with severe muscle wasting. The abdomen was markedly distended by free fluid and there was a palpable fluid wave. The degree of abdominal distension hampered abdominal palpation for organomegaly. Three-view thoracic radiographs revealed mild lymphadenomegaly of the sternal lymph nodes. Presurgical routine blood work was performed (see results under -Ç-ÿLaboratory Results). A coagulation profile was unremarkable.

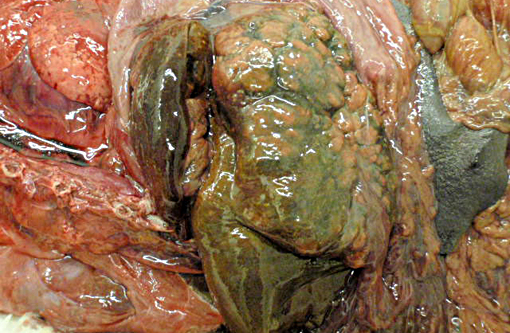

An exploratory laparotomy was performed through a ventral midline incision and 3.5 liters of a red-tinged abdominal fluid was removed. The liver was two to three times the normal size; firm to friable; and mottled red-brown and tan. Multiple, variably sized, often raised nodules were present on the hepatic surface and extended into the hepatic parenchyma. The largest nodule was approximately 15.0 cm in diameter and involved almost the entirety of the right lateral liver lobe. A partial lobectomy was performed on the left lateral liver lobe. Not all of the abnormal hepatic tissue could be removed. Multiple, small, white nodules were present in the omentum, and the wall of proximal duodenum was thickened. A hepatic biopsy; the excised portion of the left lateral liver lobe; a section of omentum; and a full-thickness duodenal biopsy were submitted for histopathologic examination.

The dog recovered uneventfully from surgery and was discharged four days after the surgery to the primary care veterinarian for continued supportive therapy and monitoring.

Following the histopathologic diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis, a fecal sample from the patient was submitted for fecal flotation examination. Parasite eggs were not identified.

The dog received a single treatment of albendazole after it returned to the primary care veterinarian. Unfortunately the dogs condition continued to decline and it died nine days after it was discharged. The owners gave their consent for a full postmortem examination.

Strict safety precautions were observed during the whole necropsy procedure. On gross examination, the body condition of the dog was poor with marked generalized muscle wasting; accentuation of all boney prominences (i.e. zygomatic arch, spine of scapula, ribs, tuber coxae); and depletion of subcutaneous and visceral adipose stores.

Gross Description:

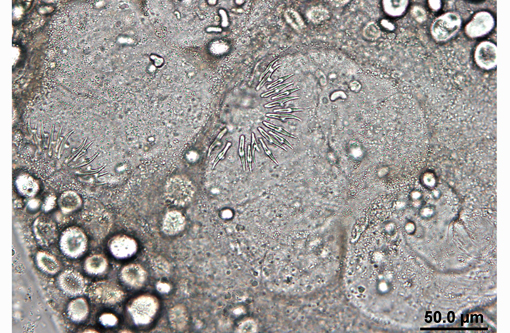

There was approximately one litre of serosanguinous fluid in the abdomen and small amounts of fibrin on the serosal surface of the intestines. Approximately 75% of the liver was replaced by multifocal to coalescing, variably raised, firm, yellow to brown masses that on cut section effaced the parenchyma, were occasionally cystic, and exuded moderate amounts pale yellow viscous fluid with white sand-like material (interpreted to be -Ç-ÿhydatid sand; see images 4-1 and 4-2). The hepatic lymph nodes, pancreas, and the adjacent mesentery contained numerous, small (approximately 4-mm in diameter) translucent cysts. The sternal, tracheobronchial, hepatic and mesenteric lymph nodes were moderately enlarged and dark black in color

Histopathologic Description:

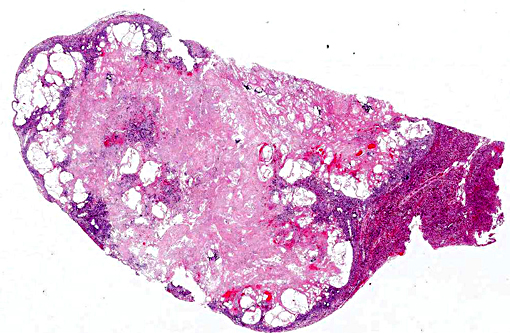

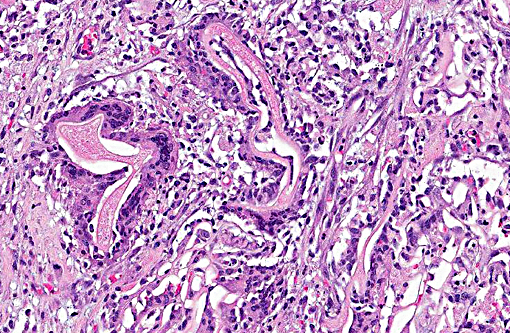

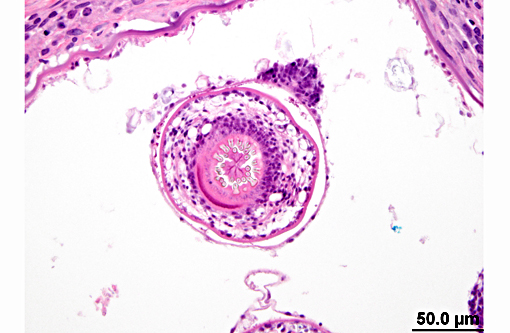

Liver: Effacing and replacing approximately 70-90% of the examined sections were optically vacant areas with multiple hydatid cysts that were lined by a thin bladder wall and contained numerous calciferous bodies and metacestode protoscoleces that had a parenchymatous body, calcareous corpus-cles, and rostellar hooks which were variably surrounded by large numbers of epithelioid macrophages, foreign body and Langhans-type giant cells, neutrophils, hemorrhage, necrotic hepatocytes, and extensive areas of fibrosis. Multifocally, large numbers of degenerate neutrophils and necrotic cellular debris surrounded the hydatid cysts and occasional cysts were mineralized. In the surrounding parenchyma, hepatocytes frequently contained granular and globular intracytoplasmic, gold-brown material (interpreted to be hemosiderin and/or bile, respectively), clear vacuoles (vacuolar degeneration) and were separated and individualized by bands of fibrous connective tissue (fibrosis) and foamy and streaming eosinophilic material admixed with postmortem bacteria (autolysis artifact).

Lymph node (hepatic): Approximately 50-70% of the cortex and medulla in the examined sections were replaced and distorted by large optically vacant areas with small numbers of hydatid cysts containing metacestode protoscoleces and were surrounded by fibroblasts and collagen. There were marked numbers of hemosiderophages in the subcapsular sinus and throughout the trabecular and medullary sinuses.

Mesentery: Multifocally, there were small numbers of collapsed hydatid cysts associated with extensive areas that were infiltrated by large numbers of fibroblasts, macrophages, giant cells, neutrophils, and fewer lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Pancreas: There were large optically vacant spaces and small numbers of protoscoleces were seen in these spaces.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

The cyst contents and abdominal fluid were submitted for PCR. Based on the band size, PCR for both of these samples was considered positive for Echinococcus multilocularis. PCR amplification and sequencing was performed on liver tissue using in-house primers developed by Dr. Karen Gesy for the cob, cox1 and nad2 mitochondrial genes; the alveolar hydatid cyst of Echinococcus multilocularis found in this dog grouped with European-type strains of the cestode.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The life cycle of E. multilocularis involves wild canids and rodents.(7) The adult tapeworms live in the intestines of a carnivore (primarily foxes and to a lesser extent coyotes, wolves and wild felids) and produce eggs that are shed in the feces. Eggs passed in the feces of the definitive host are immediately infective for the intermediate hosts. Rodents (typically voles, lemmings and deer mice), the intermediate hosts, ingest the eggs which develop into a multilobed larval form (metacestode stage; hydatid cyst) in the liver and abdomen. The metacestode stage consists of aggregations of small vesicles (cysts) in which protoscoleces are produced by the germinal layer in natural intermediate hosts. The cyst aggregates form alveolar structures composed of numerous cysts of irregular shapes with dimensions between less than 1 and 10mm (in some hosts up to 2030 mm). The cysts contain a highly variable number of protoscoleces or they may be sterile (no protoscolex formation) and partially calcified. Progressive budding and expansion of the cyst causes severe tissue damage and may result in the spread of metacestodes to other tissues, as present in this case, where the metacestode stage was found in the local lymph nodes, pancreas, and mesentery. The life cycle is completed when a carnivore ingests a rodent infected with the cyst stage of the parasite. Dogs, and less commonly cats, can be definitive hosts (i.e. adult tapeworm develops in the small intestine) when they ingest an infected rodent. Rarely, as in this case, the dog can act as an intermediate host (develop the metacestode larval stage) likely by ingesting eggs shed in the feces of wild carnivores, pets or even their own feces. People become infected with the larval stage when they ingest eggs in the soil; food or water contaminated with feces of wild carnivores or pets; or less commonly, through close association with infected animals.

Until 2009, E. multilocularis was considered to be endemic in wildlife in only two regions of Canada: the northern tundra zone of the Canadian territories and the southern Prairie Provinces, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.(3,8,9) Cases involving domestic dogs had not been reported in Canada. In 2009, hepatic alveolar hydatid disease (HAD) was diagnosed in a 3-year-old dog that had lived only in the British Columbia.(8,9) In 2012, a second case of HAD was diagnosed in a 2-year-old dog that had resided in only two parts of southern Ontario.(2) This dog is the third case to be reported in a domestic dog in Canada. The dog was acquired from a breeder in northeastern Alberta and lived most of its life in southern Alberta. The dog had brief visits to British Columbia (Vancouver Island) and Manitoba. At the time of its death the dog had been residing in southern Manitoba for a couple of months. While in southern Alberta the dog had plenty of opportunity to come in contact with the feces of wild carnivores. It is likely the dog acquired the infection while residing in southern Alberta.

Genetic analysis of tissue from the dogs in British Columbia and Alberta grouped with strains of E. multilocularis from west-Central Europe. The origin of the European-type strains of E. multilocularis in these Canada dogs is unclear but appears to be associated either with the importation of domestic dogs into Canada from Europe, since cestode treatment at the time of importation is not required or the historic importation of red foxes into North America from Europe for hunting and the fur trade.(8)

In Canada, human cases of alveolar hydatid disease are rare with a single case being reported in Manitoba in the 1930`s. There is currently no evidence to suggest cases of alveolar hydatid disease are occurring in people in Canada. However, cases of alveolar hydatid disease in domestic dogs are not only of clinical interest, but also of epidemiological importance as they are indicators of environmental contamination with E. multilocularis eggs and likely represent the main infection route for humans in North America.(5, 7, 6)

The antemortem diagnosis of alveolar hydatid disease in dogs is difficult. Spontaneously excreted proglottids are very small and are only occasionally detected on the surface of fecal samples by the animal owner or at laboratory examination. By flotation techniques taeniid eggs may be detected in fecal samples, but morphological differentiation of the eggs of E. multilocularis, E. granulosus and the Taenia species inhabiting the intestine of domestic dogs and cats is not possible.(7) In routine practice, abdominal masses of unclear origin in dogs and other animals can be assessed by fine needle aspiration cytology for tumour identification or exclusion. In this case, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology did not confirm a metacestode infection. Molecular diagnostics performed on fresh and formalin-fixed tissues, abdominal fluid and fluid samples from the hepatic cysts did help to establish the diagnosis in this case and may be useful in establishing the antemortem diagnosis.

The post mortem diagnosis of alveolar hydatid disease in aberrant hosts is based on pathognomonic macroscopic and histopathologic findings, and in doubtful cases, on results of immunological and molecular tests. Although alveolar hydatid disease of the liver is rare in dogs, it should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in cases of space-occupying lesions in the liver, even in a young dog.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The differential diagnosis discussed by participants included cysticercosis, denoting the larval form of many Taenia genera cestodes, although most agreed the multiloculated nature of the cysts and the appearance of the laminated cyst wall was fairly distinctive for hydatid cysts despite the absence of protoscolices. Cysticerci (second stage taeniid larva) have a thick fluid filled bladder (hence the name bladderworm), one or more scolices which are usually inverted, and are often surrounded by a fibrous capsule formed by the intermediate host. The structure has a series of hooks and suckers that allow it to attach to host tissue.(1) See the table below for a list of taeniid tapeworms with larval stages commonly found in mammalian intermediate hosts.

Echinococcus granulosus typically parasitizes wild canids as the definitive host, but the intermediate host is usually a large domestic species, such as cattle, sheep and horses among others. Wild canids pass the proglottids in areas where these animals graze, and upon ingestion the embryos develop into hydatid cysts. The cysts are most commonly found in the liver and lungs, although other organs can be infected; they may never result in clinical disease, but can result in carcass condemnation at time of slaughter.(4) In contrast to E. multilocularis, hydatids of E. granulosus are unilocular in nature and do not infiltrate but rather expand and compress adjacent tissue as space occupying structures, and may rupture or leak fluid, causing a hypersensitivity reaction.(1) Hydatid sand refers to the cyst fluid containing free protoscolices from ruptured brood capsules, of which the contributor provides an excellent image.

References:

1. Bowman DD. Georgis Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:132, 140-145, 388-391.

2. Brooks A, Skelding A, Stalker M, et al. Alveolar hydatid disease (Echinococcus multilocularis) in a dog from southern Ontario. AHL Newsletter. Mar 2013;17(1)8.

3. Catalano S, Lejeune M, Liccioli S, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis in urban coyotes, Alberta, Canada. Emerg Infect Diseases. 2012;18(10):1625-1628.

4. Cullen JM, Brown DL. Hepatobiliary system and exocrine pancreas. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease E edition. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:436.

5. Deplazes P and Eckert J. Veterinary aspects of alveolar echinococcosis- a zoonosis of public health significance. Vet Parasitol 2001;98:65-87.

6. Deplazes P, van Knapen F, Schweiger A, Overgaauw PAM. Role of pet dogs and cats in the transmission of helminthic zoonoses in Europe, with a focus on echinococcosis and toxocarosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011;182:41 53.

7. Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin FX, Pawłowski ZS. WHO/OIE Manual on Echinococcosis in Humans and Animals: a Public Health Problem of Global Concern. Paris:World Organisation for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties; OIE) and World Health Organization (WHO); 2001.

8. Jenkins EJ, Peregrine AS, Hill JE, et al. Detection of European Strain of Echinococcus multilocularis in North America. Letter to editor. Emerg Infect Diseases. 2012;18(6):1011-1012.

9. Peregrine AS, Jenkins EJ, Barnes B, et al. Alveolar hydatid disease (Echinococcus multilocularis) in the liver of a Canadian dog in British Columbia, a newly endemic region. Can Vet J. 2012;53:870-874.