Signalment:

Histopathologic Description:

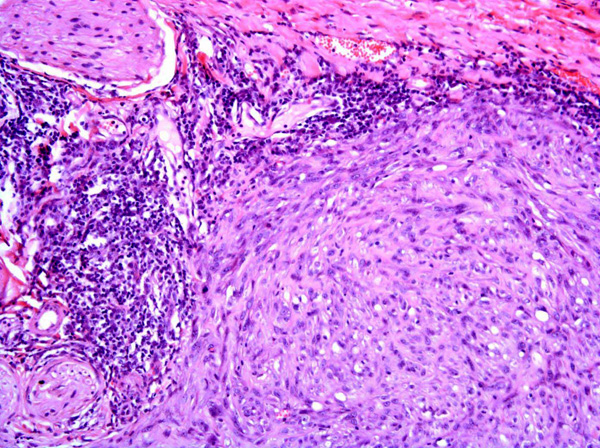

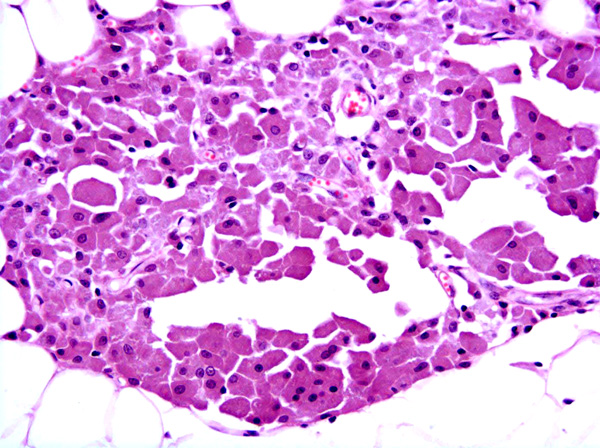

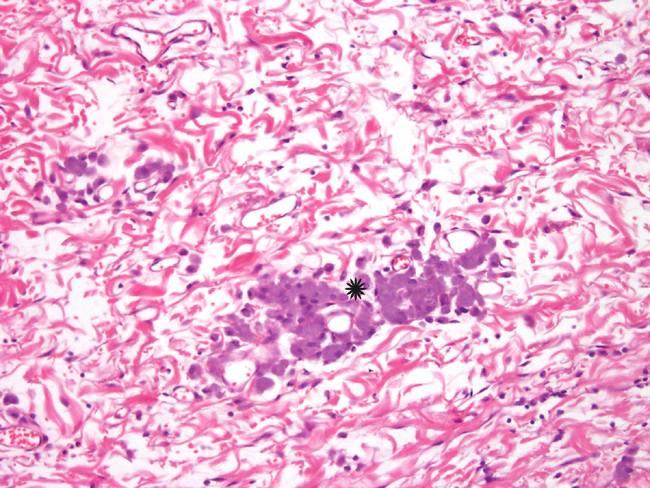

In some sections, the tumor contained poorly defined, variably-sized irregularly-shaped cystic cavities. The cystic cavities contained eosinophilic material, cellular debris, foamy macrophages, mildly basophilic fluid and/or red blood cells (Fig. 6).Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Feline vaccine-associated sarcomas (FVAS), also known as post-vaccine and vaccine-induced sarcomas, are most commonly associated with the administration of killed feline leukemia (FeLV) and rabies vaccines.11,15 The tumors are located in the subcutis of the common vaccination sites e.g. dorsal neck, interscapular region, dorsolateral thorax, hindleg and dorsal lumbar region.3,7,8 The most common type of vaccine-associated sarcoma is the fibrosarcoma8, which was observed in this case. Other sarcomas which have been reported in a similar setting include rhabdomyosarcomas8, osteosarcomas8, chondrosarcomas8, malignant fibrous histiocytomas8 and myofibroblastic sarcomas.5

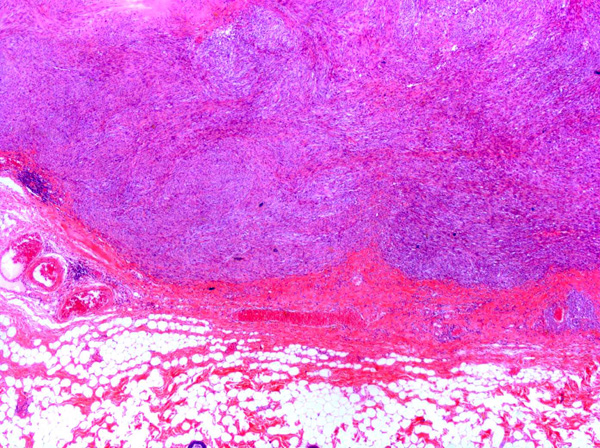

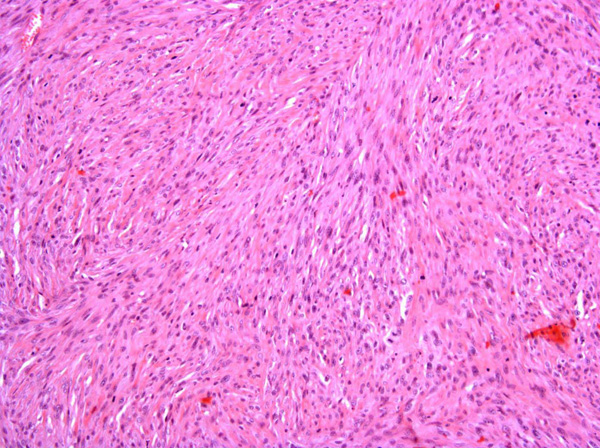

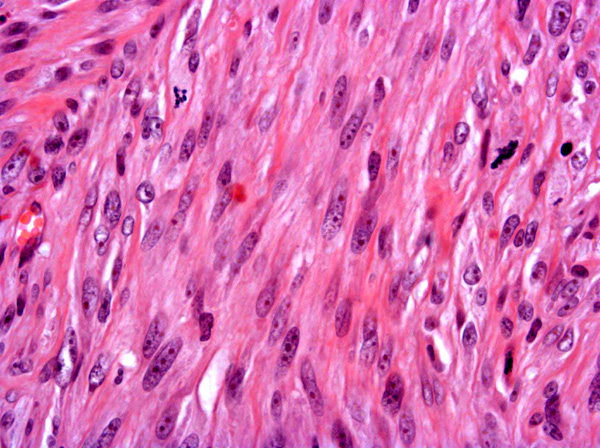

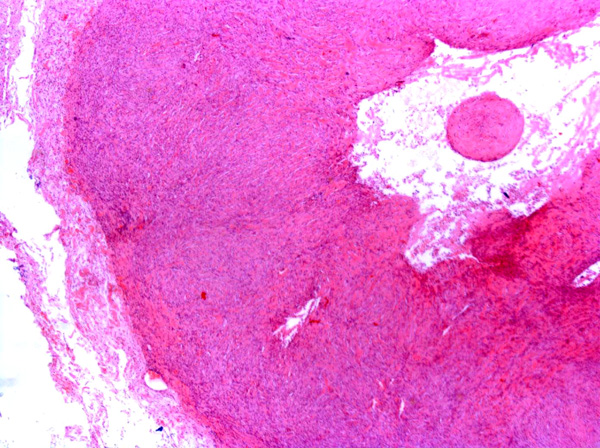

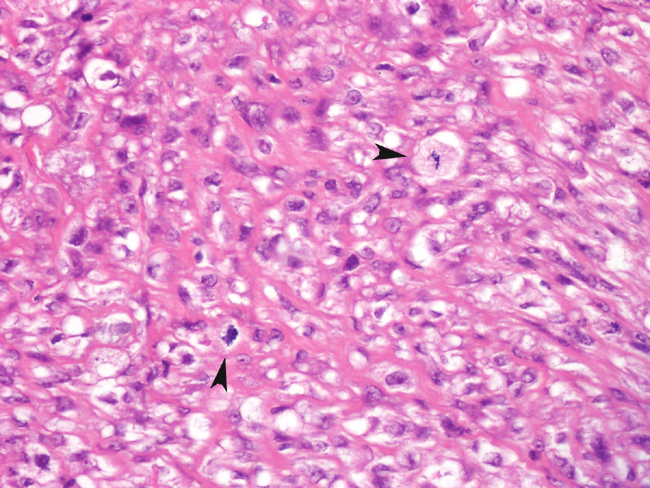

Fibrosarcomas are composed of spindle cells arranged in interlacing bundles, are located in the dermis and/or subcutis and are often circumscribed, but can have infiltrative margins. In vaccine-associated fibrosarcomas, spindle cells are admixed with histiocytoid cells and scattered multinucleated giant cells.8,16 Microscopic features differentiating feline vaccine-associated fibrosarcomas from non-vaccine associated fibrosarcomas include prominent inflammation (peripheral lymphocytic aggregates)2,3,8, presence of large histiocytic cells with intracytoplasmic bluish-grey material1,2,7 and areas of cavitation.2 In comparison to nonvaccine-associated fibrosarcomas, vaccine-associated fibrosarcomas are considered to have a higher degree of cellular pleomorphism and more inflammation.3 The bluish-grey intrahistiocytic material contained aluminum by electron probe x-ray microanalysis.7 Aluminium hydroxide is a common adjuvant used in killed feline leukemia (FeLV) and rabies vaccines. In feline VAS, a positive correlation was observed between increased number of neoplastic multinucleated giant cells and higher tumor grade, whereas the tumor grade was not influenced by the degree of inflammation.2

The average age of cats with vaccine-associated fibrosarcoma is younger (with a median age of 8 years) than the age of cats affected by non-vaccine associated fibrosarcomas (with a median age of 11 years).3 Feline vaccine-associated fibrosarcomas are locally invasive and aggressive with a high rate of local recurrence and more rare metastases to draining lymph nodes10, mediastinum 20 and lungs.1,20

Although the exact pathogenesis of vaccine-associated sarcomas is unknown, an association between persistent antigenic stimulation, chronic inflammation and/or wound healing and neoplastic transformation of primitive mesenchymal cells resulting in soft tissue sarcomas is suspected.15 After subcutaneous injection of rabies vaccine, focal granulomatous injection-site reactions often with central necrosis, peripheral lymphocytic aggregates and presence of globular grey-blue material within the cytoplasm of some macrophages have been reported.6 The growth factors FGF-b and TGF?, which are involved in wound healing and neoplastic transformation of mesenchymal cells, are expressed by tumor cells in feline VAS.19 Based on ultrastructural16 and immunohistological8 studies, myofibroblasts which are involved in wound healing, have been identified in feline VAS.Â

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) plays a role in the migration and proliferation of fibroblasts.13 By using VAS cell lines, it was shown that neoplastic cells of VAS express the Platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR- _) and that inhibition of this receptor inhibited cell growth.12 Mutations of the tumor suppressor gene p53, which are genomic alterations involved in tumorigenesis14, have also been identified in feline VAS.18 In addition, over-expression19 and altered expression10 of the P53 protein, which is most commonly caused by mutation of its gene, have been detected in feline VAS.Â

Feline vaccine-associated sarcomas and feline post-traumatic ocular sarcomas4,22 are similar in morphology and pathogenesis: both tumors can be composed of a spectrum of sarcomas suspected to arise within a background of persistent inflammation or wound healing.4, 15

Sarcomas associated with vaccination sites have also been reported in ferrets17 and dogs.21 Microscopic features of these tumors are similar in all species.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Sarcomas in cats have also been associated with subcutaneous administration of long acting drugs and with the presence of foreign materials, such as non-absorbable suture or microchips. Ocular sarcoma may develop following ocular trauma.22

References:

2. Couto SS, Griffey SM, Duarte PC, Madewell BR: Feline Vaccine-associated Fibrosarcoma: Morphologic Distinctions. Vet Pathol 39: 33-41, 2002

3. Doddy FD, Glickman LT, Glickman NW, Janovitz EB: Feline Fibrosarcomas at Vaccination sites and Non-vaccination sites. J Comp Path 114: 165-174, 1996

4. Dubielzieg RR, Everitt J, Shadduck JA, Albert DM: Clinical and morphological features of posttraumatic ocular sarcomas in cats. Vet Pathol 27: 62-65, 1990

5. Dubielzieg RR, Hawkins KL, Miller, PE: Myofibroblastic sarcoma originating at the site of rabies vaccination in a cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 5: 637-638, 1993

6. Hendrick MJ, Dunagan CA: Focal necrotizing granulomatous panniculitis associated with subcutaneous injection of rabies vaccine in cats and dogs: 10 cases (1988-1989). J Am Vet Med Assoc 198: 304-305, 1991

7. Hendrick MJ, Goldschmidt MH, Shofer FS, Wang Y, Somlyo AP: Postvaccinal sarcomas in the cat; epidemiology and electron probe microanalytical identification of aluminum. Cancer Res 52: 5391-5394, 1992

8. Hendrick MJ, Brooks JJ: Postvaccinal sarcomas in the cat: Histology and immunohistochemistry. Vet Pathol 31: 126-129, 1994

9. Hershey AE, Sorenmo KU, Hendrick MJ, Shofer, FS: Prognosis for presumed feline-associated sarcoma after excision: 61 cases (1986-1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1: 58-61, 2000

10. Hershey AE, Dubielzig RR, Padilla ML, Helfand SC: Aberrant p53 Expression in Feline Vaccine-asssociated Sarcomas and Correlation with prognosis. Vet Pathol 42: 805-811, 2005

11. Kass PH, Barnes WG, Sprangler WL, Chomel, BB, Culbertson MR: Epidemiologic evidence for a causal relation between vaccination and fibrosarcoma tumorigenesis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 203: 396-405, 1992

12. Katayama R, Huelsmeyer MK, Marr AK, Kurzman ID, Thamm DH, Vail DM: Imatinib mesylate inhibits platelet-derived growth factor activity and increases chemosensitivity in feline vaccine-associated sarcoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 54: 25-33, 2004

13. Kumar V, Abul A, Faustro N: Tissue Renewal and Repair: Regeneration, Healing and Fibrosis. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Kumar V, Abul A, Faustro N, 7th ed., pp. 87-118. Elsevier Inc, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania , 2005

14. Kumar,V, Abul, A, Faustro, N: Neoplasia. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, eds. Kumar V, Abul A, Faustro N, 7th ed., pp.269-342. Elsevier Inc, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania , 2005

15. Macy DW, Hendrick MJ: The potential role of inflammation in the development of postvaccinal sarcomas in cats. Review in Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Prac 26: 103-109, 1996

16. Madewell BR, Griffey SM, McEntee MC, Leppert VJ, Munn RJ: Feline-associated Fibrosarcoma: An Ultrastructural Study of 20 Tumors (1996-1999). Vet Pathol 38:196-202, 2001

17. Munday JS, Stedman NL, Richey LJ: Histology and Immunohistochemistry of Seven Ferret Vaccination-site Fibrosarcomas. Vet Pathol 40: 288-293, 2003

18. Nambiar PR, Jackson ML, Ellis, JA, Chelack BJ, Kidney BA, Haines DM: Immunohistochemical Detection of Tumor Suppressor Gene p53 Protein in Feline Injection Site-associated Sarcomas. Vet Pathol 38: 236-238, 2001

19. Nieto A, Sanchez MA, Martinez E, Rollan E: Immunohistochemical Expression of p53, Fibroblast Growth Factor-b, and Transforming Growth Factor-_ in Feline Vaccine-associated Sarcomas. Vet Pathol 40: 651-658, 2003

20. Rudmann DG, Van Alstine WG, Doddy F, Sandusky GE, Barkdull T, Janovitz EB: Pulmonary and mediastinal metastases of a vaccine-site sarcoma in a cat. Vet Pathol 33: 466-469, 1996

21. Vascellari M, Melchiotti E, Bozza MA, Mutinelli F: Fibrosarcomas at Presumed Sites of Injection in Dogs: Characteristics and Comparison with Non-vaccination Site Fibrosarcomas and Feline Post-vaccinal Fibrosarcomas. J Vet Med 50: 286-291, 2003

22. Zeiss CJ, Johnson EM, Dubielzig RR: Feline Intraocular Tumors May Arise from Transformation of Lens Epithelium. Vet Pathol 40: 355-362, 2003