Signalment:

Gross Description:

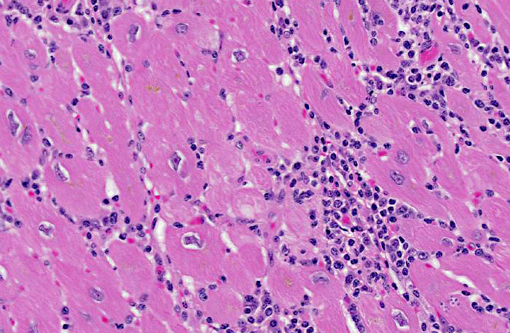

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

A review of the database of pathologic lesions diagnosed within our colony over the last thirty years revealed no other cases of severe trypanosomiasis, and even mild cases were rare. Pest control procedures are well established and vigilantly enforced; no increased incidence of pests (either rodents or triatomine beetles) was noted before or since the identification of this case. In May of 2005 a survey of sixty apparently normal animals from this colony revealed a single animal with a positive culture. Serendipitously, the animal presented in this case was included in that study and had a negative culture at that time. This case is considered unusual, due to the high number of leishmanial forms of Trypanosoma cruzi organisms that are present within pseudocysts in individual cardiomyocytes as well as the abundant inflammatory reaction. At locations where pseudocysts have ruptured a suppurative inflammatory reaction is observed; however, the primary inflammatory population within this lesion is mononuclear, composed primarily of lymphocytes, macrophages and plasma cells. The affected animal was in late pregnancy when she presented for annual physical examination. During routine sedation, the animal became cyanotic and when emergency drugs failed to elicit any positive response the animal was euthanized. Potential immune suppression associated with pregnancy or mildly advanced age may have resulted in the development of this protozoal infection; alternatively, a concentrated mucocutaneous exposure secondary to ingestion of the vector may have led to this disease.(5,6)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

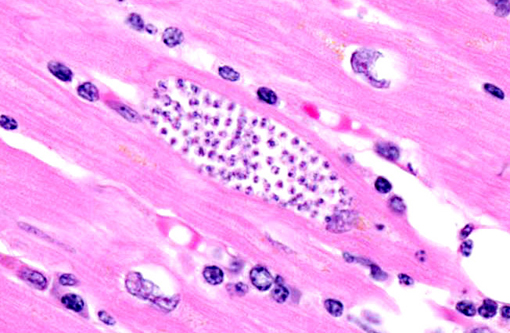

T. cruzi occurs in three morphologic forms. Epimastigotes are found within the arthropod vector, while the extracellular trypomastigote (blood form) and intracellular amastigote (tissue form) occur within the mammalian host. The amastigote contains a large round nucleus and a rod-like kinetoplast similar to that of Leishmania sp.(7,8) Leishmanial and trypanosomal amastigotes are anecdotally described as having rod-shaped kinetoplasts oriented perpendicular and parallel to the long axis of the oval nucleus, respectively; however, most current references simply describe a juxtanuclear kinetoplast composed of DNA and representative of the mitochondrial genome,(3) which led conference participants to conclude that kinetoplast orientation relative to the nucleus is not an accurate or reliable method for distinguishing Trypanosoma sp. from Leishmania sp. Readers may refer to WSC 2011-2012, Conference 18, case 1 for further discussion of Trypanosoma cruzi.

African trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness, also occurs in humans and a variety of animal species. It is transmitted through the saliva of the tsetse fly (Glossina sp.). Unlike T. cruzi, African trypanosomes are capable of continuous antigenic variation of their outer glycoprotein coat in order to evade the host immune response. They also produce sialidases, which hydrolyze host cell membrane sialic acid and facilitate invasion. In addition to myocarditis, ocular involvement, anemia, thrombocytopenia and even disseminated intravascular coagulation have been reported in association with African trypanosomiasis.(8)

In this case, anesthesia likely led to decompensation of existing cardiac disease. There is multifocal cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, characterized by fiber thickening and change of the nuclei from spindle/cigar shaped to box car like (rectangular). Additionally, cardiomyocytes often contain aggregates of golden-brown granular pigment, interpreted as lipofuscin, which represents intralysosomal accumulation of cellular debris (i.e., residual bodies).(9) There is also mild slide variation, with varying degrees of myocardial fibrosis (demonstrated with a Massons trichrome stain) depending on the section; however, fibrosis is a common background finding in macaque hearts(2) and may not be a direct result of the trypanosome infection. Conference participants briefly discussed the differential diagnosis for the gross and histological findings, including leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis, sarcocystosis, encephalitozoonosis and African histoplasmosis. Histochemical staining with giemsa highlights the presence of moderate numbers of intracellular cardiomyocyte protozoal amastigotes with a rod-like kinetoplast, consistent with trypanosomiasis or leishmaniasis. It can be difficult to differentiate Trypanosoma spp. from Leishmania spp.; however, the kinetoplast of T. cruzi is typically larger, and leishmanial amastigotes tend to concentrate in the phagocytic cells of the skin, mouth, nose and throat, or in the macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system, which are all uncommon sites for T. cruzi.(1) Based on the species, its geographic location and the anatomic location of the lesions, trypanosomiasis is the most likely diagnosis; however, since additional diagnostic testing, such as PCR, culture or serology was not performed, leishmaniasis cannot be completely ruled out.

References:

2. Chamanza R, Marxfeld HA, Blanco AI, Naylor SW, Bradley AE. Incidences and range of spontaneous findings in control cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) used in toxicity studies. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38:642-657.

3. Cheville NF. Ultrastructural Pathology: The Comparative Cellular Basis of Disease. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:529-536.

4. Cicmanec JL, Neva FA, McClure HM, Loeb, WF. Accidental infection of laboratory-reared Macaca mulatta with Trypanosoma cruzi. In: Laboratory Animal Science. 1974;24(5):783-787.

5. Gleiser CA, Yaeger RG, Ghidoni JJ. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a colony-born baboon. J Vet Med Assoc 1986;189(9):1225-1226.

6. Kasa TJ, Lathrop GD, Dupuy HJ, Bonney CH, Toft JD. An endemic focus of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a subhuman research colony. J Vet Med Assoc. 1977;171(9):850-854.

7. Kunz E, Matz-Rensing K, Stolte N, Hamilton PB, Kaup FJ. Reactivation of a Trypanosoma cruzi infection in a rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) experimentally infected with SIV. Vet Pathol. 2002;39:721-725.

8. Snowden KF, Kjos SA. Trypanosomiasis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:722-734.

9. Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:551-555.