Signalment:

Three-year-old,

male, English setter mix, (

Canis familiaris).The

three-year-old intact male English setter mix was picked up by county animal

control when it was found roaming freely in a small rural community in Southern

Arizona. Aspirate cytology from the preputial mass and several cutaneous

masses were submitted.

Gross Description:

The dog

had a large ulcerated circumferential mass effacing the preputial mucosa and

numerous variably sized cutaneous masses throughout the caudal dorsum, right

and left flank, and inguinal regions. The superficial cervical lymph nodes

were enlarged.

Histopathologic Description:

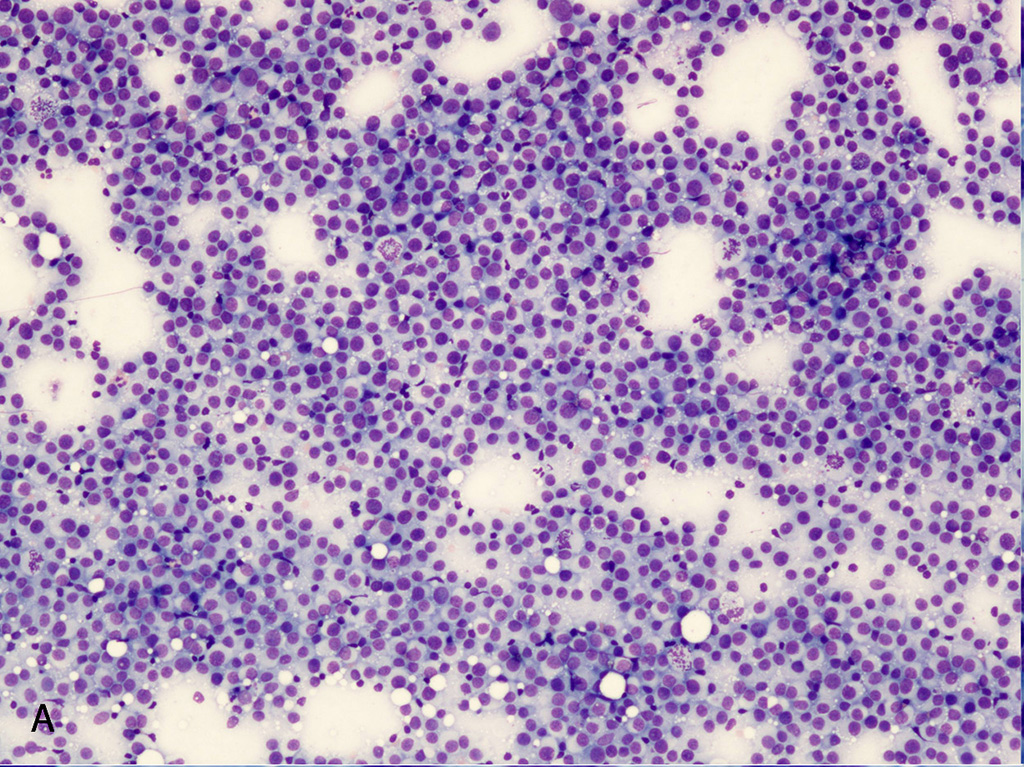

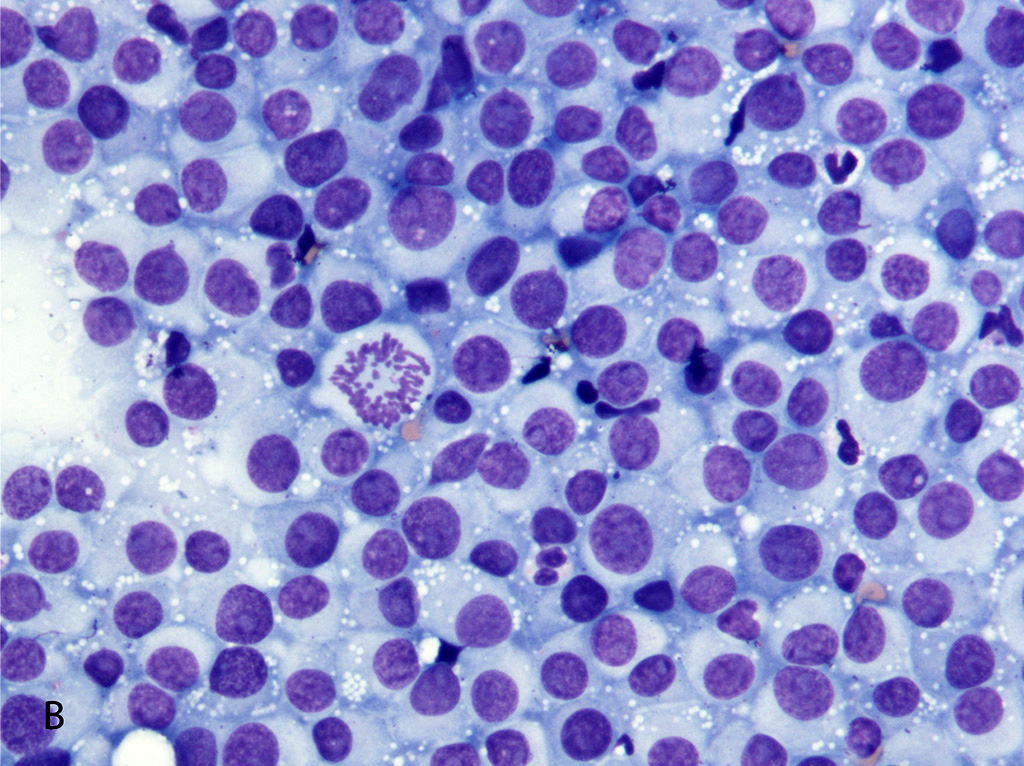

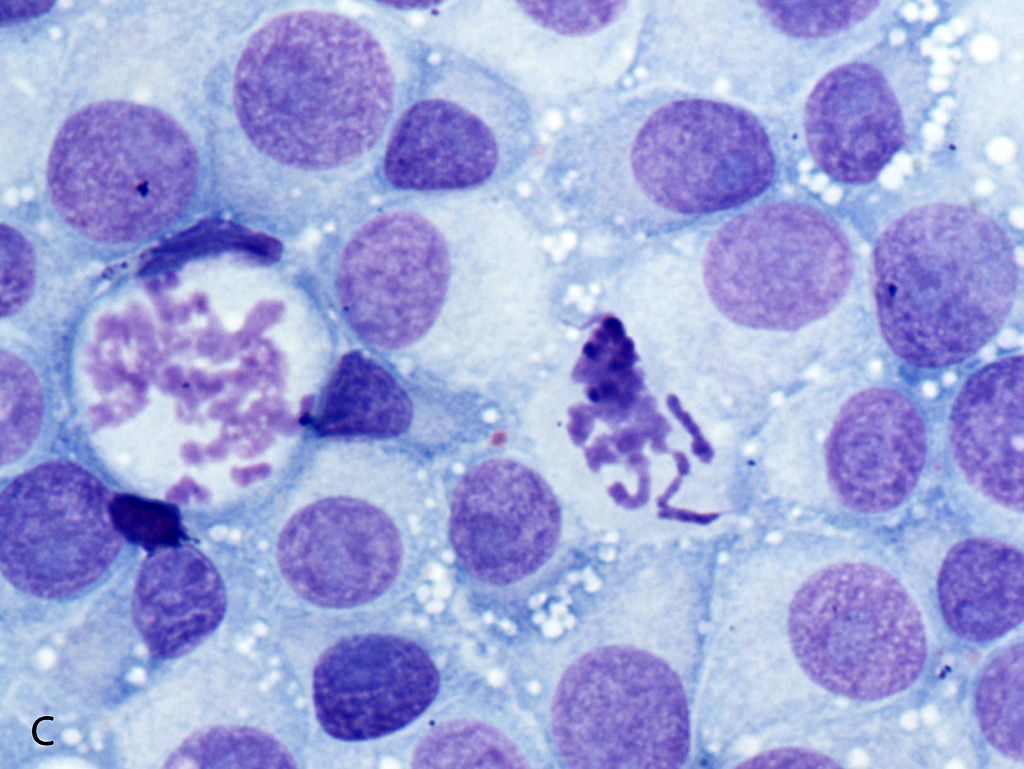

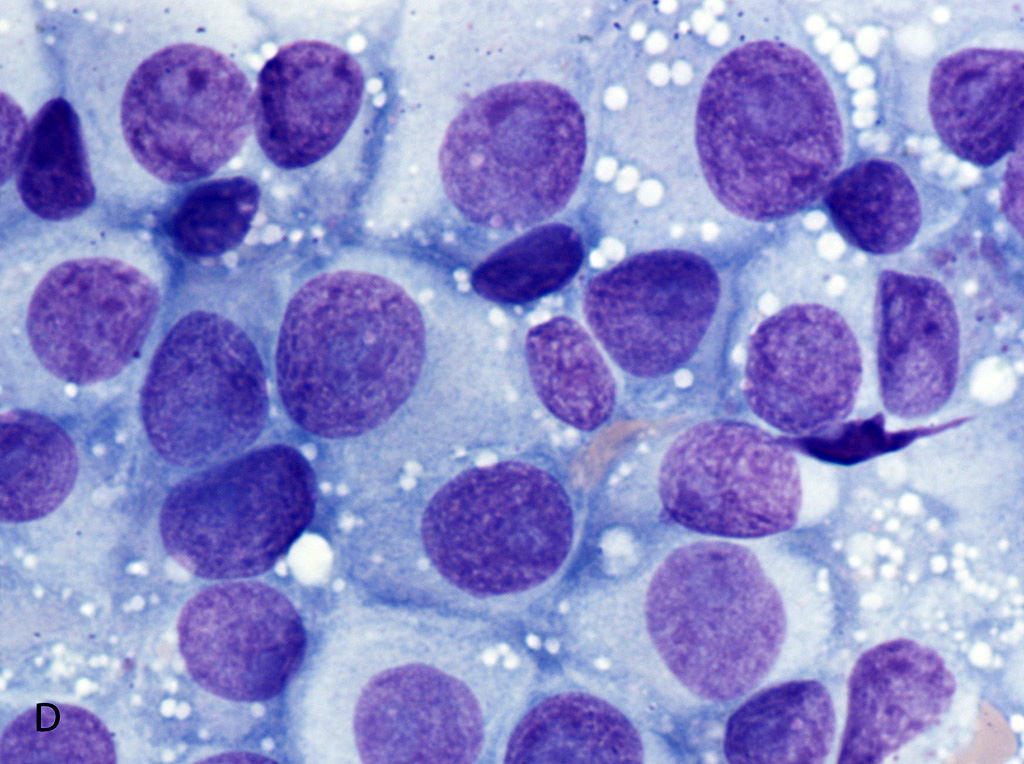

The aspirate preparations from the dermal masses all revealed the same

process. The preparations have high cellularity with large numbers of intact

cells for evaluation. There is minimal hemodilution. The nucleated cell

population consists of round cells with moderate anisokaryosis and

anisocytosis. The nuclei are round with coarse ropey chromatin and often

have a single large pale lightly basophilic nucleolus. The cytoplasm is lightly

basophilic and contains small to moderate numbers of discrete round vacuoles.

Mitotic figures are common and atypical mitoses are seen. There are occasional

neutrophils and small lympho-cyte seen intermixed with the neoplastic round

cells. The cytology

preparations from the prepuce showed the same cytological findings.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Transmissible venereal tumor (TVT) metastatic to skin.

Lab Results:

The dog was

positive for

Ehrlichia canis using in-house ELISA testing.

Condition:

Transmissible venereal tumor

Contributor Comment:

Transmissible venereal tumor is a transplantable neoplasm that affects members

of the canid family (domestic dogs, coyotes, foxes, and wolves).

3

The tumor has a global distribution and highest prevalence in regions with

limited canine population control. The tumor spreads by sexual contact and is

usually localized to the mucosal surface of the external genitalia of both male

and female dogs. However, masses have been reported in the mucosal surfaces of

the nasal passage, oral mucosa, anus, and conjunctival surfaces of the eye.

3,7

Metastatic disease is not common but has been documented. In most cases,

metastasis is to the regional lymph nodes, but extension of the neoplasm to

skin, kidney, brain, bone, peritoneum, and other tissues has been reported.

1,3

The tumor cells are aneuploid and have a unique long interspersed nuclear

element (LINE-1) that may be useful to confirm TVT origin in cases involving

tumors in unusual sites.

10,12

While

TVT is a relatively uncommon tumor in most of the United States, rural areas

that have higher numbers of intact dogs, such as many parts of Southern

Arizona, cases are seen on a regular basis. The histological and cytological

characteristics of the neoplastic cells along with the location of the mass in

association with the external genitalia make the diagnosis of this tumor

relatively straight forward. In this case, the cytological and histological

findings from the skin lesions and the preputial lesion were identical

supporting metastatic disease. There is one report of a prepubertal female dog

without any genital involvement.

4 It is proposed that the tumor

cells were transplanted from the dam by cohabitation and grooming/social

behaviors. While multicentric disease cannot be ruled out, it is unlikely that

multiple sites of transplantation through intact haired skin would explain the

presence of the skin lesions in this adult male dog with a concurrent preputial

mass.

JPC Diagnosis:

Fine

needle aspirate, cutaneous mass: Transmissible venereal tumor, English setter

mix,

Canis familiaris.

Conference Comment:

Canine trans-missible venereal

tumor (TVT), also known as Sticker tumor or venereal granuloma, is an extremely

old and remarkably stable transmissible cancer that first arose in canids

approximately 11,000 years ago.

2,5 Based on genetic studies, the

founder breed is thought to be closely related to wolves or ancient Eastern

Asian dog breeds.

1 TVT dispersed across several continents about 500

years ago and is currently found on every continent in the world other than

Antarctica.

5,12 It is the oldest known continuously passaged somatic

cell lineage.

5 As mentioned by the contributor, TVT is mainly

transmitted during coitus, but can also be transmitted by licking, biting, or

rubbing behaviors.

2,8 The infecting cells are physically

transplanted and grow as a xenograft in host tissue. Neoplastic cells are

thought to be of histiocytic origin and are immune-positive for vimentin,

lysozyme, alpha-1-antitypsin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, and are

immune-negative for cytokeratin, S100, and muscle markers.

1,2,9

Typical gross findings of TVT include solitary or

multiple papillary, nodular, ulcerated, and inflamed masses on the mucous

membranes of the penis, prepuce, vulva, and vagina, and/or skin and subcutis of

the head, neck, limbs, trunk, scrotum, and perineum. There is occasional extension

to the uterus and cervix.

2,9 A recent study demonstrated ocular

lesions as the single manifestation of TVT with extension to the adjacent

conjunctiva and nictitating membrane, presumably by extra-genital inoculation.

3

As mentioned by the contributor, metastasis uncommonly occurs in the draining

lymph node.

9

After transmission, tumorous lesions typically appear within

two months. Conference participants discussed the patho-genesis of the tumor

growth, stabilization, and regression phases. The initial growth stage is

called the progressive phase (P). During the P phase, almost all TVT cells lack

expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I and II due to production

of inhibitory cytokine transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta). This allows

the TVT cells to grow and evade immune destruction by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. After three to

nine months, the tumor stabilizes and begins to spontaneously regress. During the regression (R) phase, interleukin-6 (IL-6) from

infiltrating lymphocytes is thought to work in conjunction with

interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) to antagonize TGF-beta and increase MHC I and II

expression on TVT cells.

1,8-10

In addition to TVT, conference participants also discussed

the devil facial tumor disease (DFTD), which is an emerging rapidly fatal

transmissible tumor that is decimating the wild Tasmanian devil population.

8,11

This tumor is of Schwann cell origin and is spread through biting. Tumors occur

primarily in the mouth, head, and neck. DFTD cells evade immune destruction via

production of TGF-beta and down regulation of MHC-I and II expression, similar

to TVT. However, unlike TVT, spontaneous regression has not been reported in

DFTD, and mortality occurs in all affected animals via starvation and frequent

metastasis.

8 Other transmissible tumors include clam leukemia of

soft shell clams and the contagious reticulum cell sarcoma of Syrian hamsters

first described in the 1960s.

6,8,11

References:

1. Ganguly B, Das U, Das AK. Canine transmissible venereal

tumor: A review.

Comp Oncol. 2016; 14(1):1-12.

2. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK.

Skin Diseases

of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2005:800-803.

3. Komnenou AT, Thomas AL, Kyriazis AP, et al. Ocular

manifestations of canine trans-missible venereal tumor: A retrospective study

of 25 cases in Greece.

Vet Rec. 2015; 176(20):523-527.

4. Marcos R, Santos M, Marrinhas C, et al. Cutaneous

transmissible venereal tumor without genital involvement in a prepubertal

female dog.

Vet Clin Pathol. 2006; 35:106109.

5. Murchison EP, Wedge DC, et al. Transmissible dog cancer

genome reveals the origin and history of an ancient cell lineage.

Science.

2014; 343:437-440.

6. Ostrander EA, Davis BW, Ostrander GK. Transmissible tumors:

Breaking the cancer paradigm.

Trends Genet. 2016; 32:1-15.

7. Park MS, Kim Y, Kang MS, et al., Disseminated transmissible

venereal tumor in a dog.

J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006; 18(1):130-133.

8. Pye RJ, Woods GM, Kreiss A. Devil facial tumor disease.

Vet

Pathol. 2016; 53(4):726-736.

9. Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG,

ed.

Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3.

6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:448-449.

10. Setthawongsin

C, Techangamsuwan S, Tangkawattana S, et al. Cell-based polymerase chain

reaction for canine transmissible venereal tumor (CTVT) diagnosis.

J Vet Med

Sci. 2016; 78(7):1167-1173.

11. Siddle

HV, Kaufman J. A tale of two tumours: Comparison of the immune escape

strategies of contagious cancers.

Mol Immunol. 2013; 55:190-193.

12. VonHoldt

BM, Ostrander EA. The singular history of a canine transmissible tumor.

Cell.

2006; 126(3):445-447.

1.