Signalment:

Nine-year-old, female spayed, Greyhound, (

Canis familiars).The dog presented for a 2-month history of vomiting and diarrhea and later anorexia, which were partially responsive to antibiotics. She also had a history of left forelimb lameness. Ultrasound revealed a thickened gastric wall with loss of layering and enlarged gastric lymph nodes. Cytology on ultrasound-guided fine needle aspirate of the stomach revealed a gastric carcinoma. Radiographs of the left front limb revealed multiple radiolucent medullary lesions. On the day of euthanasia, the dog developed left hind limb lameness.

Gross Description:

The dog weighed 23 kg, had a body condition score of 3/5 and was in fair postmortem condition. An area measuring 9cm x 3cm had been removed post mortem from the antrum, pylorus, and duodenum for purposes of tumor tissue banking. The tissue remaining at the pyloric-duodenal junction was 5 to 7 mm thick, firm and white to gray on cut surfaces. The pancreas was nodular, firm and up to 8 mm thick with multifocal areas of hemorrhage. There was a mild to moderate amount of petechiae and ecchymoses throughout the small and large intestinal mucosa. Three of the lymph nodes adjacent to the stomach were 1.3 to 1.5 cm in diameter, firm, dark red on the capsular surface and tan on section. Multiple round, white, soft to hard nodules (3 to 4 mm in diameter) were present throughout the medulla of the left humerus.

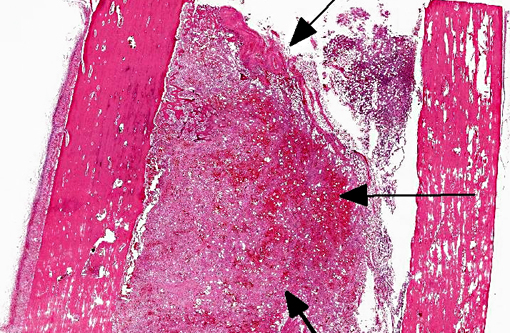

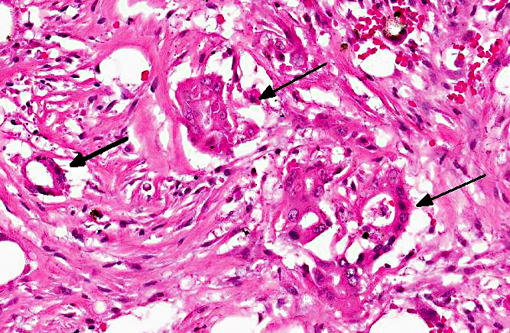

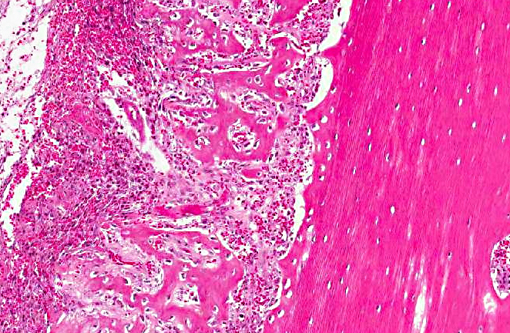

Histopathologic Description:

Tissue is from the diaphysis of the left humerus. The lesions are most marked in the medullary cavity with marked infiltration with solid to occasionally acinar carcinoma associated with marked reactive fibrosis and marked reactive woven bone. Marrow cavity not involved with reactive woven bone or reactive fibrosis has mixed fatty and hematopoietic marrow. In some sections, there is tumor infiltrate into this mixed marrow without reaction. Not present on all slides is invasion of tumor into the cortex with variable cortical bone lysis, cortical bone necrosis and periosteal reactive woven bone formation. Neoplastic cells are not apparent in the periosteal lesion.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Left humerus: moderately differentiated, metastatic, solid carcinoma (presumed of gastric origin based on post mortem findings) with marked medullary reactive fibrosis and woven bone formation, variable cortical bone lysis and variable periosteal woven bone formation.Â

Condition:

Metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma

Contributor Comment:

Carcinoma was confirmed in the stomach and based on pattern of infiltrate/absence of other primary tumors, metastatic gastric carcinoma was found in pancreas, gastric lymph nodes and left humerus. The clinical findings relevant to the left rear leg were unexplained (no lesions were apparent in the left rear leg grossly or microscopically).Â

Mammary gland and prostatic carcinoma are the major origin of metastatic carcinoma to bone in humans. Such metastatic pattern in spontaneous animal disease is rare.(4) Most carcinoma metastatic to bone cause lysis; prostatic carcinoma in dog and man can be associated with osteoblastic metastases. The mechanisms by which prostatic tissue induces reactive woven bone is unclear but seems to have an endothelin-dependent mechanism. PtH-rp and prostaglandins are likely not involved.(3) In the current case, the radiographic appearance of the lesions in the humerus were that of medullary lysis. It is difficult to explain the discrepancy between the microscopic appearance of a productive process in the medullary cavity and the radiographic interpretation of a lytic one. It is possible that because of reduced superimposition of bone, the cortical lysis (present in some sections) gave the appearance of medullary lysis radiographically. In a series of 19 dogs with skeletal metastatic carcinoma, most dogs were presented for veterinary care because of clinical signs relating to the skeletal metastasis and not the primary carcinoma.(2) In 58% of the dogs, a primary site of the carcinoma was not determined. Most skeletal metastases are in axial skeleton and proximal long bones.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Long bone: Adenocarcinoma, metastatic.Â

Conference Comment:

As the contributor states, metastasis of carcinoma to bone is rare in dogs relative to humans. Interestingly, malignant pilomatricomas appear predisposed to metastasize to bone in dogs.(1) During a review of 13 reported cases of canine malignant pilomatricoma, Carroll et al. identified seven neoplasms which metastasized to or extended into bone (sites included vertebrae, ribs, mandible, maxilla and femur). In humans, tumor metastasis to bone is most common in well-vascularized sites (axial skeleton, proximal aspect of long bones and ribs), where the microenvironment provides fertile soil for solid carcinomas.(1) For example, once human breast cancer metastasizes to bone, it produces colony stimulating factor 1, parathyroid hormone related protein, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. The resulting activation of nuclear factor kappa B ligand stimulates osteoclast formation and activation. Osteoclast degradation of bone matrix releases insulin-like growth factor 1, transforming growth factor beta and bone morphogenic proteins, which promotes survival of metastatic cells and stimulates parathyroid hormone related protein synthesis, thus resulting in a positive feedback loop of metastatic growth and osteolysis. Other factors that have been found to promote metastasis to bone in humans include chemokines in bone that attract circulating receptor-bearing tumor cells, cytokines that bind tumor cells bearing E-cadherin and laminin, and the presence of tumor associated macrophages. It is unclear if these factors play a role in the tendency of canine malignant pilomatricoma to metastasize to bone.(1)

References:

1. Carroll EE, Fossey SL, Mangus LM, Carsilo ME, Rush LJ, McLeod CG, Johnson TO. Malignant Pilomatricoma in 3 Dogs.

Vet Pathol. 2010;47(5)937-943.Â

2. Cooley DM, Waters DJ. Skeletal Metastasis as the initial clinical manifestation of metastatic carcinoma in 19 dogs.Â

J Vet Intern Med. 1998;12:288-293.

3. LeRoy BE, Sellers RS, Rosol TJ. Canine prostate stimulates osteoblast function using the endothelin receptors.Â

Prostate. 2004;59:148-156.Â

4. Rosol TJ, Tannehill-Gregg SH, LeRoy BE, Mandle S, Contag CH. Animal models of bone metastasis.

Cancer. 2007;97(3 Suppl):748-757.