Signalment:

Gross Description:

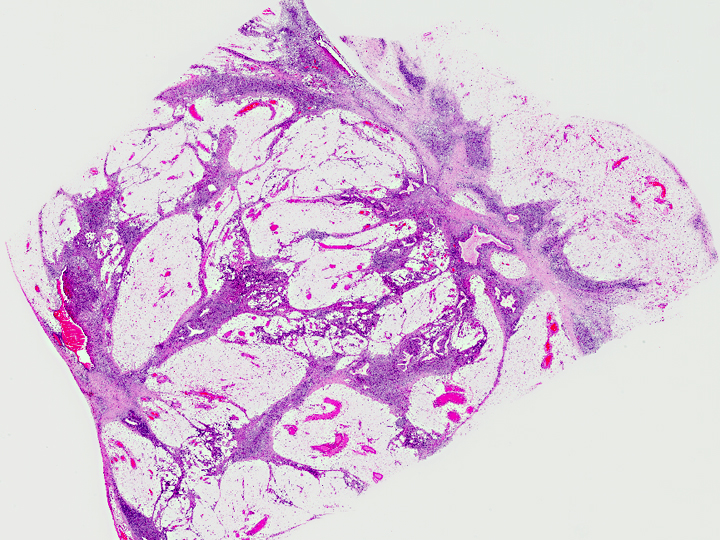

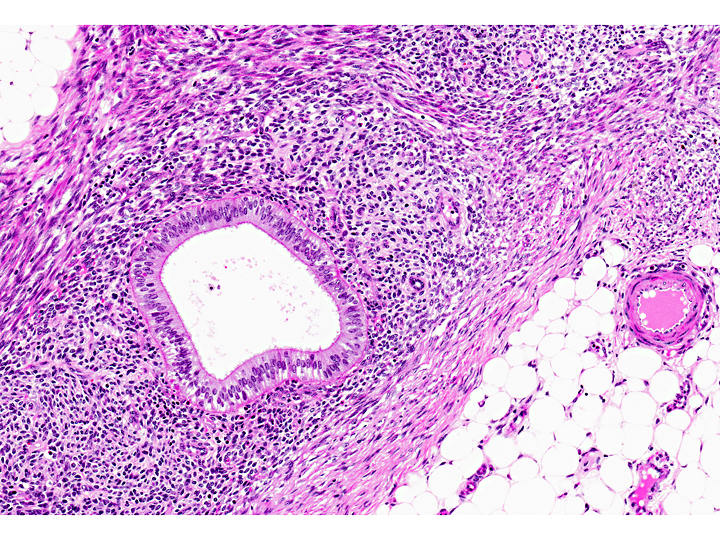

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent, chronic disease that occurs in menstruating species; which include human and non-human primates, the elephant shrew (Elephantulus myuras jamesoni) and one species of bat (Glossophaga soricina). Spontaneous endometriosis has only been reported in women and female non-human primates and the pathogenesis is not completely understood. It may be induced in other species through intra-peritoneal injection of viable endometrial tissue. Rodent models of the disease have been created in this manner. By definition, it is the presence of viable, ectopic, extra-uterine, functional endometrial glands with stroma in various sites throughout the pelvis and peritoneal cavity.(5,7)

The most widely accepted explanation of the pathogenesis is Sampsons three-fold transplantation: retrograde menstruation occurs, viable endometrial cells must be present, and adherence and implantation into structures in the peritoneum must successfully occur. Retrograde menstruation alone is not enough for the condition to occur. In some baboon studies, retrograde menstruation has been reported in over 83% of animals. Endometrial cells have been reported in the peritoneal fluid of 59-79% of women during menses. However, endometriosis is not clinically present at these rates and is estimated to affect only 15-20% of women during their reproductive lives. Other theories include vascular and lymphatic dissemination, in-situ development from Wolffian or M+�-+llerian duct remnants, and the development of metaplastic ovarian or peritoneal tissue. An alternate theory suggests induction and differentiation of mesenchymal cells that are affected by substances released by degenerating endometrial tissue following reflux into the peritoneal cavity. While the retrograde menstruation and transplantation theory is the most widely accepted, the cellular and molecular mechanisms that lead to the development of the disease are controversial. (2,4,7)

Angiogenesis, immune suppression (cytotoxic T-cells, NK cells), mesothelial lining injury and pro-inflammatory cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, adhesion molecules, toxin (dioxin) exposure and genetic polymorphisms are all among the multitude of candidate factors in the creation of the proper peritoneal environment that must exist for successful survival, adhesion and implantation to occur. In women, an autoimmune component has also been proposed due to the demonstration of auto-antibodies and an association with other autoimmune diseases and immune mediated abortion. In humans, there is a 6-9 fold increase in prevalence among first-degree relatives. (2,4,7)

Briefly, an abnormal or permissive peritoneal environment in the face of endometrial reflux is thought to be central cause for this chronic inflammatory condition. Conditions that favor tubal reflux (e.g., cervical stenosis) in addition to increased sloughing and retrograde flow may increase tubal reflux and overwhelm peritoneal macrophages ability to eliminate the sloughed endometrial material. However, it should be noted that conditions such as cervical stenosis are not present in all cases(5,7).

Chronic inflammation and the release of certain cytokines in this inflammatory stage (TNF-alpha, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-8) may alter innate immunity and permit the viable cells to persist through decreased peritoneal macrophage, natural killer cell and cytotoxic T-cell activity. However, the decreased NK cell activity has also been described as constitutive rather than a result of cytokine or hormone induced immune suppression and secretory ICAM (sICAM) expression by endometrial tissue may bind LFA-1 and help prevent NK-cell recognition of endometrial implants. (2, 5, 7)

Endometrial cells from women with endometriosis have decreased rates of apoptosis, insensitivity to macrophage cytolysis, and enhanced gene expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2, secretory ICAM (intercellular adhesion molecule), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and various matrix metalloproteinases which suggests increased intra-peritoneal viability, and ability to adhere and invade peritoneal membranes and tissues. (2, 5, 7)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants also discussed various risk factors in non-human primates which predispose them to endometriosis. These include low numbers of pregnancies, with increased numbers of menstruations throughout life, resulting in increased endometrial turnover compared to multiparous primates. Non-laproscopic abdominal surgical procedures, including hysterectomy and estradiol therapy are also implicated, as well as genetic predisposition and age. Aged non-human primates are more likely to develop endometriosis than older women because unlike human females, menstruation continues indefinitely due to lack of menopause(3).

References:

2. DHooghe, TMD, Kyama CM, Chai D, Fassbender A, Vodolaskaia, A Bokor, A and Mwenda JM: Nonhuman primate models for translational research in endometriosis. Reproductive Sciences 16 (2): 152-161, 2009

3. Fazleabas AT, Brudney A, Gurates B, Chai D, Bulun S. A modified baboon model for endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002 Mar;955:308-17; discussion 340-2, 396-406.

4. Hadfield RM, Yudkin PL, Coe CL, Scheffer J, Uno H, Barlow DH, Kemnitz JW and Kennedy SH: Risk factors for endometriosis is the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): a case-control study. Human Reproduction Update 3(2): 190-115, 1997.

5. Matarese G, De Placido G, Nikas Y and Alviggi C: Pathogenesis of endometriosis: natural immunity dysfunction or autoimmune disease? Trends in Molecular Medicine 9 (5): 223-228, 2003.

6. Mwenda JM, Kyama CM, Chai DC, Debrock S and DHooghe TMD: The baboon as an appropriate model for the study of multifactorial aspects of human endometriosis. The Laboratory Primate, 1st ed., Chapter 33, Academic Press, 2005.

7. Van der Linden PJQ: Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Human Reproduction 11(3): 53-65, 1996.