Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

PCR for Newcastle's Disease Virus (NDV) and Avian Influenza virus (AI) were negative. PCR for Infectious Laryngotracheitis virus (ILT) was positive.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Clinical signs vary from severe epizootic forms (as in this case) to mild endemic forms. Coughing, gasping and expectoration of blood-stained mucus characterize severe forms; mild forms show unthriftiness, decreased egg production nasal discharge and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Severe forms have high morbidity (90 -100%); mortality usually ranges from 10 -20%. Endemic forms have low morbidity and mortality. Although antigenically homogeneous, different virus strains with differing virulence have recently been differentiated by PCR-RFLP techniques5. Differential diagnoses for respiratory disease in chickens include the diphtheritic form of avian pox, NDV, AI, infectious bronchitis, fowl adenovirus infections and aspergillosis.

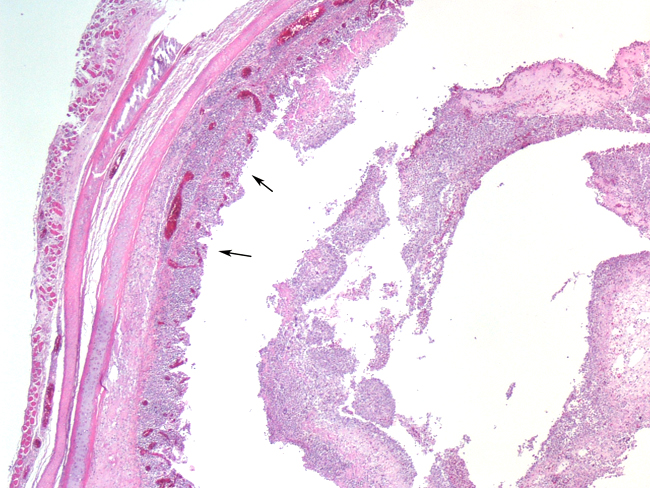

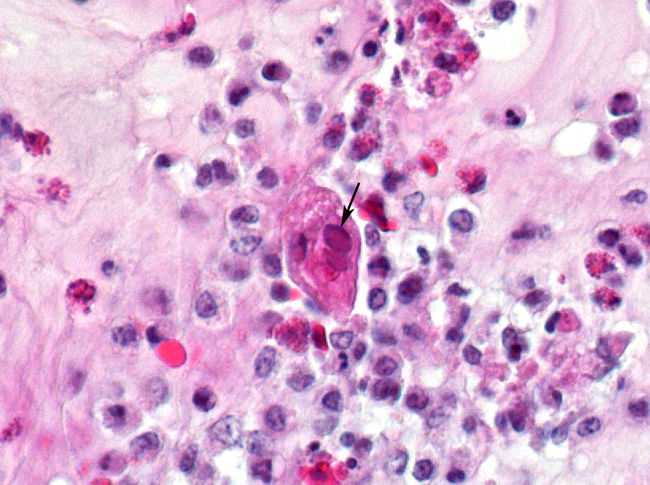

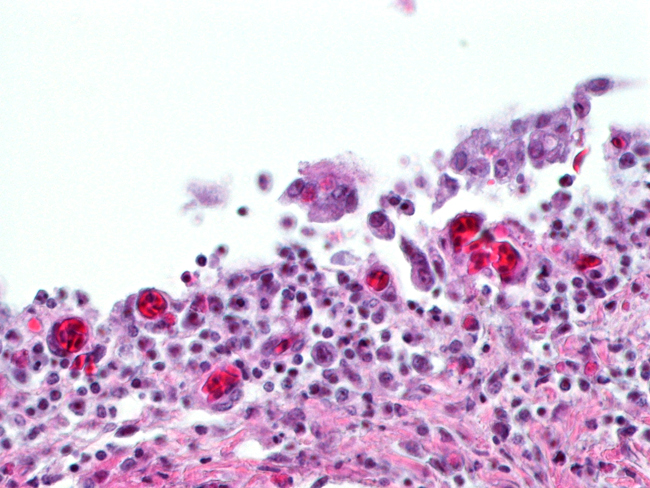

The most consistent gross lesions of ILT are in the larynx and trachea. In mild cases, the only lesions may beconjunctivitis, sinusitis and mucoid tracheitis. In severe forms, diphtheritic changes can be striking, consisting of mucoid casts along the entire length of the trachea. Mucoid plugs in the larynx (as seen in this case) are also common. In some cases, hemorrhage predominates. Histologicaly, early lesions consist of loss of goblet cells and mononuclear inflammation. As the lesions progress, respiratory epithelial cells loose cilia, enlarge and form multinucleate syncytia. Nuclear inclusion bodies are present only in early stages (1 - 5 days). Confirmatory diagnostic procedures include viral isolation on embryonated chicken eggs, serology and PCR. Control of the disease in laying flocks is generally by vaccination, whereas tight biosecurity and a shorting growing cycle will often make vaccination of broiler flocks unnecessary. Vaccines are usually modified live virus, and mixing of flock with different immunity levels can cause disease outbreaks. In this case, birds from a non-vaccinated house were mixed with vaccinated birds, causing a disease outbreak. Newer deletion mutant vaccines are underdevelopment that will not only provide a safer ILT vaccine but show promise as vector vaccines for other avian infectious diseases, such as AI 1.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Ultrastructural features are those of a typical herpes virion and include a DNA-containing core within a 100nm icosahedral capsid surrounded by a variably sized proteinaceous tegument layer and an outer envelope with incorporated viral glycoproteins.1 The viral glycoproteins appear as fine spikes projecting from the surface of the envelope.2 Viral particle sizes vary between 200- 350nm depending on the amount of incorporated tegument protein.1

Tegument proteins are common in enveloped viruses and are usually a combination of essential and non-essential proteins that are released shortly after viral entry into the cell. These proteins may aid in suppression of the immune response, suppression of host mRNA transcription, or transcribing/translating viral genes. Formation of tegument proteins is generally done late in the viral infectious cycle, following replication of viral genes.3

Viral replication of ILT is similar to that of other alphaherpes virus.1,2 Within the infected cell nucleus, viral capsids are formed and filled with viral DNA. These nucleocapsids are then enveloped by the inner nuclear membrane and deenveloped by the outer nuclear membrane when transported into the cytoplasm.1 Within the cytoplasm the capsids associate with an electron dense tegument and are enveloped by a second budding event in the trans-Golgi region. The mature virus particles are then released by exocytosis.1

A list of common veterinary alpha-herpesviral infections is included in table 2-1.4

Table 2-1. Alphaherpesviruses4

|

References:

2. Guy JS, Bagust TJ: Laryngotracheitis. In: Diseases of Poultry, ed. Saif YM, 11th ed., pp. 121-131. Iowa State Press, Ames, IA, 1997

3. Yeung BJ, McHamstein HY, McHamstein M: Herpes simplex virus tegument Protein V1 elucidation and formation around the nucleocapsid. J Virol 28:1262-1274, 2007

4. Murphy FA, Gibbs EPJ, Horzinek M, Studdert MJ: Herpesviridae. In: Veterinary Virology, 3rd ed., pp. 301- 325. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 1999

5. Kirkpatrick NC, Mahmoudian A, Colson CA, Devlin JM, Noormohammadi AH: Relationship between mortality, clinical signs and tracheal pathology in infectious laryngotracheitis. Avian Pathol 35:449-453, 2006

6. Sellers HS, Garcia M, Glisson JR, Brown TP, Sander JS, Guy JS: Mild infectious laryngotracheitis in broilers in the southeast. Avian Dis 48:430-436, 2004