CASE 1: A18-11077 (4118172-00)

Signalment:

7-yr-old, male (neutered), domestic shorthaired cat (Felis catus), cat

History:

An acute episode of hemolytic anemia occurred in the cat five days after a dental prophylaxis. Following a transfusion, the cat improved for several weeks, then became increasingly depressed, anorexic, anemic, and thrombocytopenic, accompanied by vomiting and hematemesis. Euthanasia was elected and a necropsy performed.

Gross Pathology:

A necropsy was performed on a 7-year-old, 3.5 kg, neutered male, domestic shorthaired cat in fair physical condition. Autolysis was mild. Mucous membranes were pale pink. The heart weighed 18 g (0.51% of body weight), with a 0.6 cm thick left ventricular free wall, 0.1 cm right ventricular free wall, 0.6 cm thick interventricular septum. The lungs were mottled pink to dark red, soft, and air-filled. The liver weighed 100g (2.8% of body weight) and was mottled green-tan to red. The spleen weighed 18 g (0.51% of body weight) and was dark red and plump.

Laboratory results:

N/A

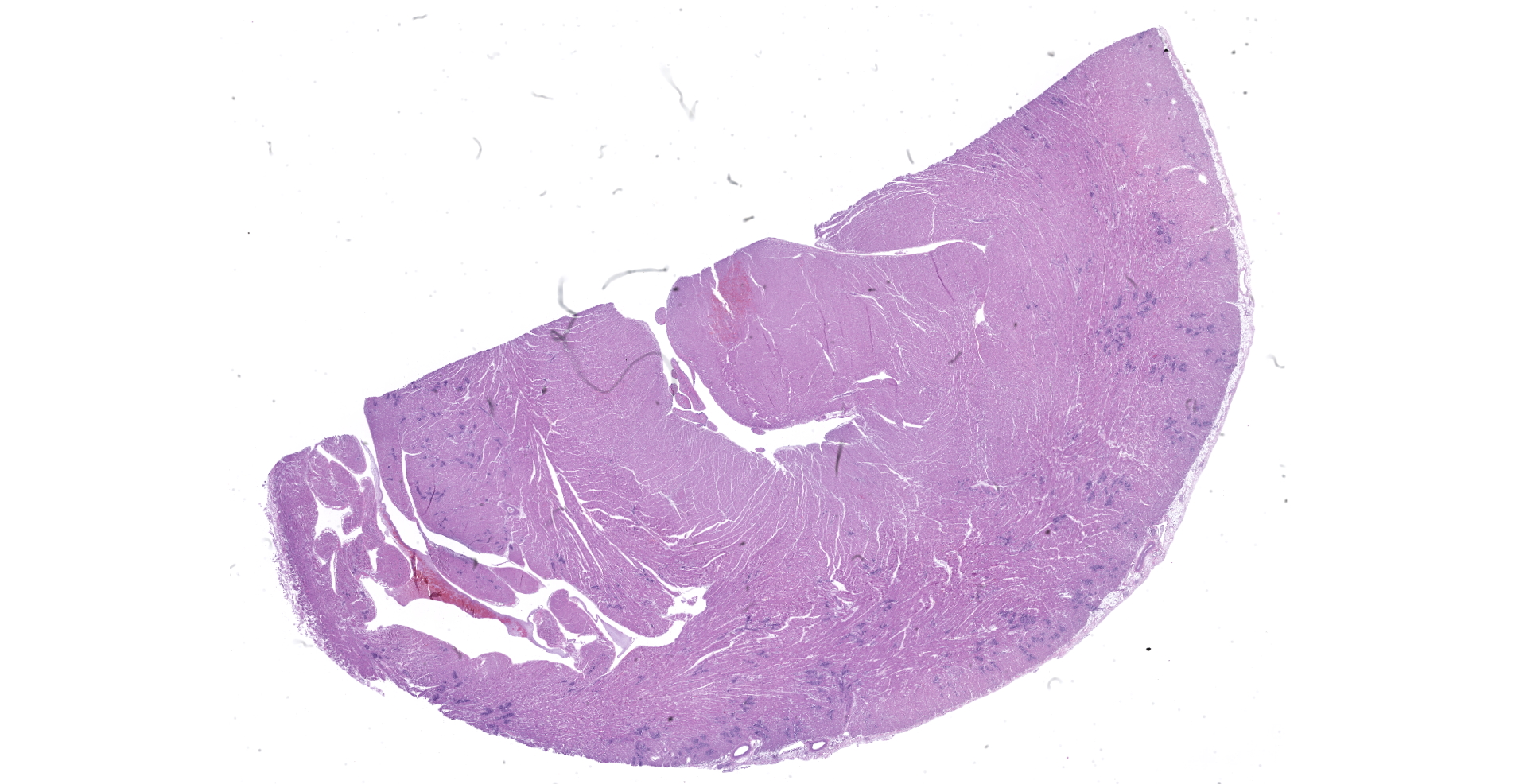

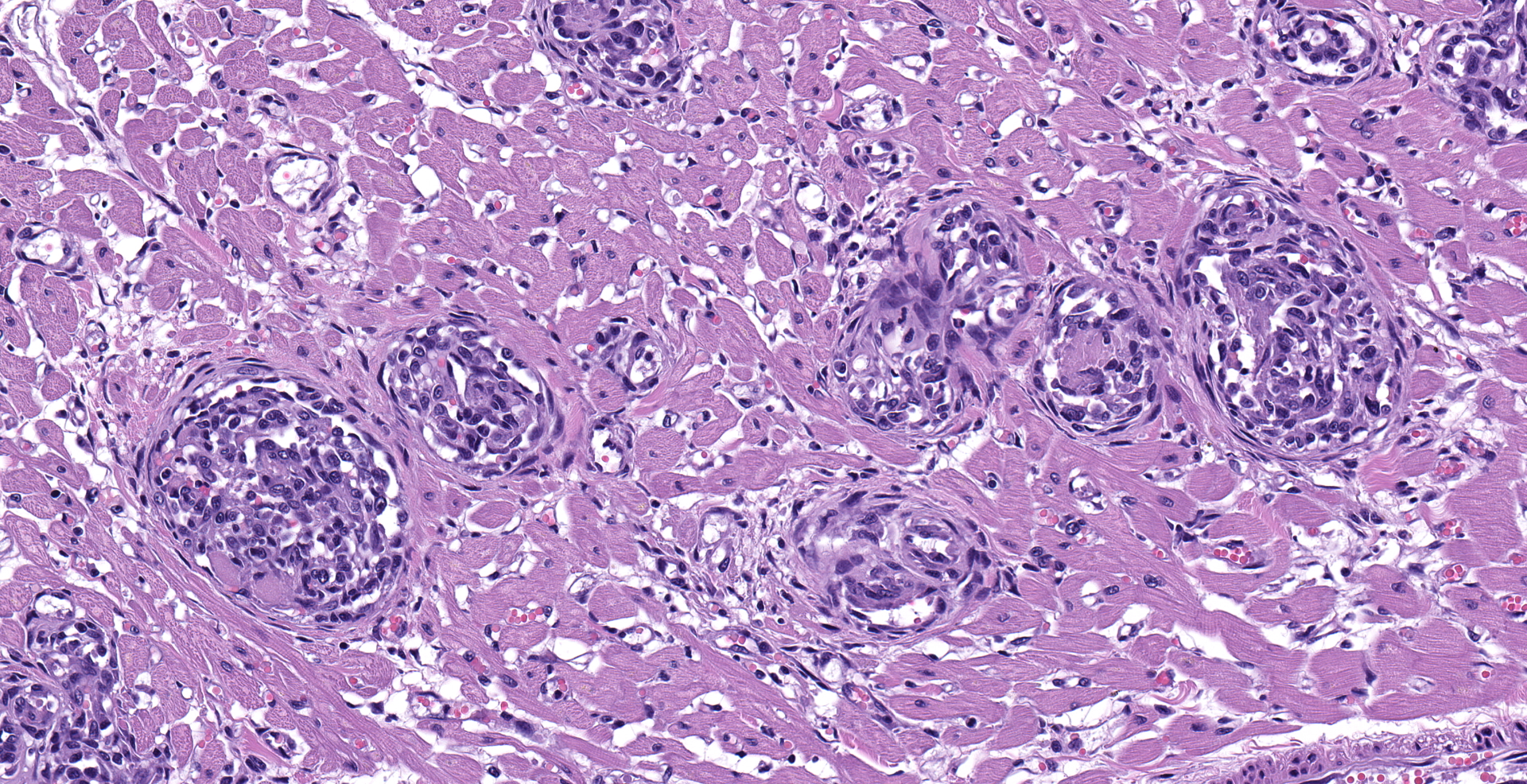

Microscopic description:

Heart: Multifocally, myocardial arterioles in the left and right ventricle and interventricular septum are expanded and occluded by fibrin thrombi, erythrocytes, and intravascular spindle cell proliferation. Spindle cells are often plump, with round to oval nuclei, densely stippled chromatin and pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tunica media is occasionally infiltrated by eosinophilic, homogenous material (fibrin) and edema. These arterioles are often surrounded by streams of pale eosinophilic fibrosis and associated fibroblasts, with corresponding myofiber disarray. Approximately 10% of the myocyte population has one of the following changes: degeneration with swollen, hypoeosinophilic, vacuolated sarcoplasm; necrosis with eosinophilic sarcoplasm, loss of cross striations, and pyknotic nuclei or regeneration with enlarged multinucleation.

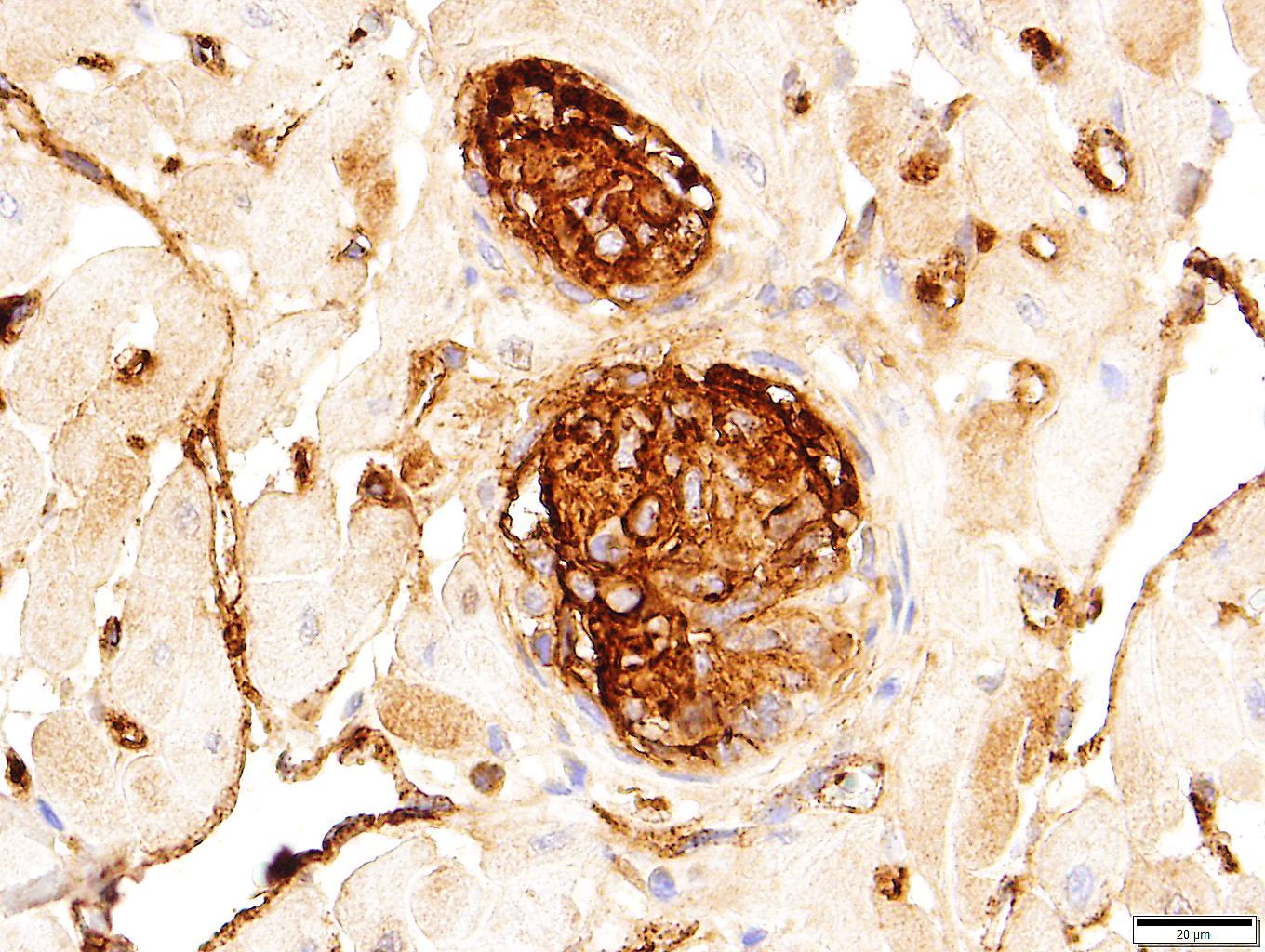

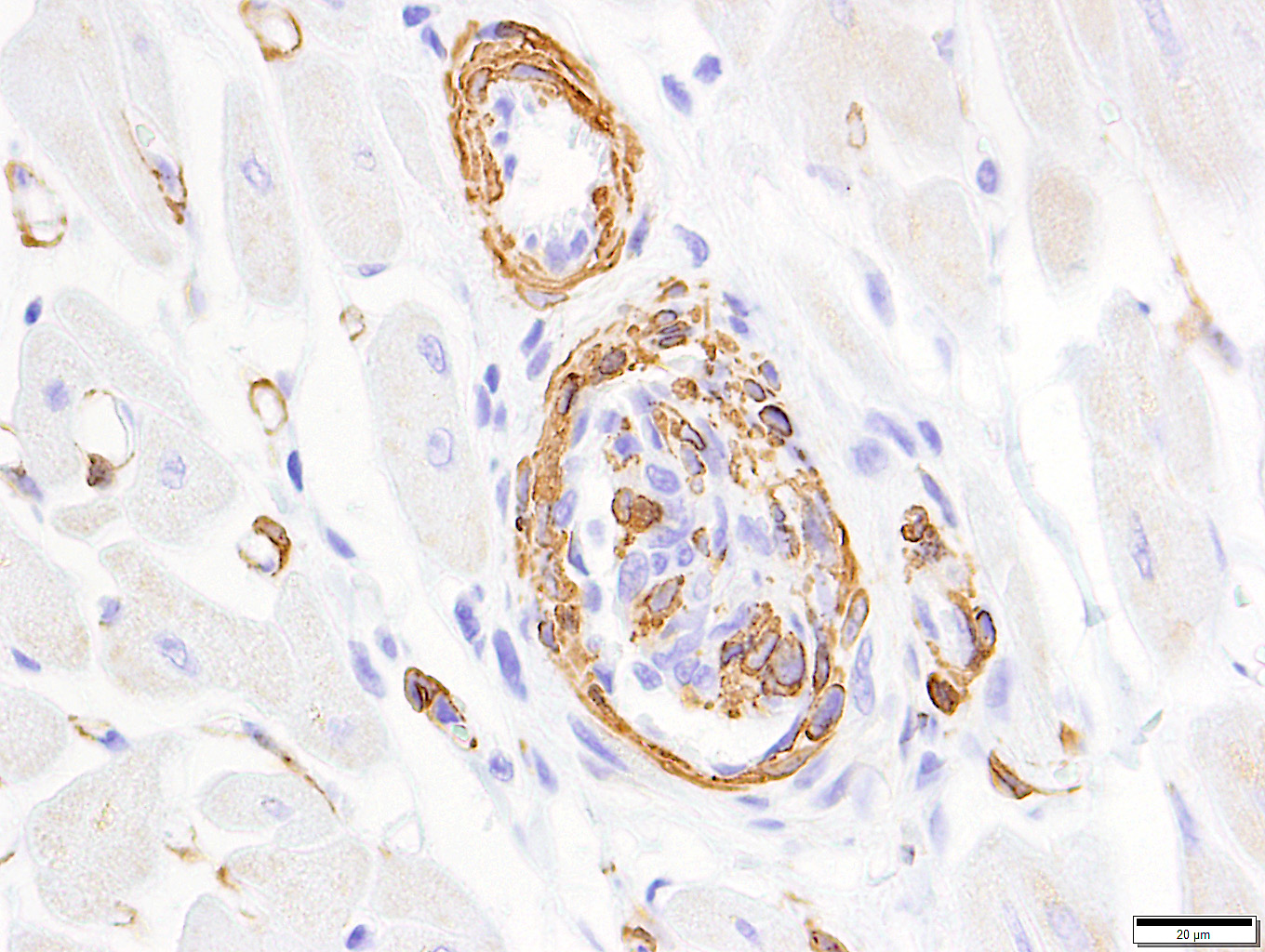

Among the proliferating spindle cell population in the heart, immunohistochemical staining of cytoplasm was widespread and strongly positive for vimentin and von Willebrand's factor. Pericytes and scattered cells within the proliferating cells stained positive for smooth muscle actin. Immunohistochemical staining for Bartonella spp. was negative.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Heart: Intraluminal and mural vascular spindle cell proliferation, multifocal, chronic, moderate to marked; with multifocal thrombosis and perivascular edema

Myocardial degeneration and necrosis, focal, chronic, moderate; with fibrosis

Contributor's comment:

Histologic lesions and immunohistochemistry results are consistent with the feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis (FSRA).

Feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis (FSRA) is a rare, multisystemic intravascular proliferative disorder.4 Affecting domestic cats almost exclusively, a similar condition has been reported in a Corriente steer.2,3,4,7,8 Intravascular proliferative disorders in cats are represented by a malignant angiotropic lymphoma, with immunohistochemical properties of T cells, and a condition with histologic and immuno-histochemical features similar to human reactive angioendotheliomatosis (RAE). In humans, RAE is a benign process limited to the skin that is characterized by proliferation of intravascular endothelial cells mixed with smaller numbers of pericytes. Similar intravascular proliferations occur in cats as the fatal multisystemic disease, feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis (FSRA).4 Ultrastructural and immuno-histochemical findings reveal the two distinct populations of spindle cells. Lesions are dominated by endothelial cells expressing von Willebrand's factor and smaller numbers of pericytes that express smooth muscle actin.4,7

The disease is seen most commonly in juvenile to young adult male cats of no specific breed. Clinical signs and gross lesions are varied and non-specific, including anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, vomiting, hemorrhages, hematuria, anemia, icterus, seizures and other neurologic signs, thrombocytopenia, and spontaneous death. While a number of these signs, including thrombocytopenia, were present in this case, there was no evidence of respiratory distress, pulmonary edema, pericardial or pleural effusion suggestive of cardiac insufficiency.3,4,7,8 Affecting primarily small arterioles of the heart, lesions also occur frequently in the kidneys, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, brain and meninges, eyes, and pancreas. The liver, spinal cord, adrenal glands, thyroid, subcutis, lung, and bone marrow are less commonly affected. Other findings include multifocal fibrin thromboses, hemorrhages, and acute myocardial necrosis. Death is likely the result of cardiac insufficiency.4 In addition to changes in the heart, fibrin thrombi and/or intravascular spindle cell proliferation was present in arterioles of the brainstem, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, renal cortices, lung, liver, spleen, pancreas, intestinal submucosa, and adrenal glands of this cat.

The pathogenesis of FRSA is poorly understood, although the presence of two cell populations and lack of cellular atypia, suggests a reactive proliferative process rather than a neoplastic one.4 A number of other occlusive, intra-arteriolar proliferative disorders in humans involve mixed populations of endothelial cells and pericytes. These glomera or glomeruloid structures have involved certain cases of chronic glomerulonephritis, pulmonary hypertension, and cases of chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Possible mechanisms for the lesion include an exaggerated response to thrombosis, unusual immune-mediated vasculitis, or exuberant angiogenesis related to angiogenic cytokines and/or dysfunctional endothelial regulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis.4

Infectious diseases in humans with HIV-AIDS have been associated with proliferative endothelial lesions. These include Kaposi's sarcoma, caused by human herpesvirus-8, and bacillary angiomatosis, caused by Bartonella henselae and B. quintana. Although information is limited, associations between infection with FIV, FeLV, and FIP virus in cats with FRSA have not been made.4,7 It has been shown that infection with one or more Bartonella sp. may contribute to the pathogenesis of FRSA in cats and hemangiopericytomas in other animals.1 Immunohistochemical staining of multiple tissues for Bartonella spp. was negative in this case.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology

College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30602

www.vet.uga.edu/VPP

JPC diagnosis:

Heart, arterioles: Atypical endothelial and pericyte proliferation (angioendotheliomatosis), diffuse, severe, with fibrin thrombi and adventitial fibrosis.

JPC comment:

The contributor concisely summarizes this relatively uncommon disease in cats. While the presentation of human reactive angioendotheliomatosis differs from that of cats, they are histologically similar, with both proliferating endothelial cells and pericytes comprising the lesions. In a case report from 2006, a 57-year-old intact woman was diagnosed with cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatosis. Her medical history included a history of vascular disorders which included both deep vein thrombosis and a significantly lower measured blood pressure on her left arm, with a bruit of the left subclavian artery. She also had elevated anticardiolipin antibody IgG and decreased protein C levels. Activated protein C is a critical factor in anti-coagulative effects, and anticardiolipin antibodies has been shown to lower levels of protein C, leading to pro-coagulative states. In humans, anticardiolipin antibodies are found in approximately 23% of patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and is associated with thrombotic events. It has been suggested that one possible pathogenesis of this disease is vascular occlusion leading to localized hypoxia and acidosis, followed by hyperplasia of endothelial cells and pericytes in an attempt to recanalize vessels and restore perfusion of tissues.5

While too few cases of FSRA have been reported to make subclassifications, there have been proposals to make distinctions in possible subtypes of human reactive angioendotheliomatosis. Subtypes may include diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA), acroangiodermatitis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiomatosis associated with cryoproteins (also called angiopericytomatosis). A more recent proposal is to include an entity characterized by a benign proliferation of histiocytes within the lumena of cutaneous vessels (intravascular histiocytosis).6

While it cannot be stated definitively that human reactive angioendotheliomatosis and FSRA share a similar pathogenesis, there is biologic plausibility. Perhaps these young cats experience an endotheliotropic pathogen, or a subsequent immune complex disease, which alters Virchow's triad and their anticoagulative homeostasis. A potential direction to turn for research may be immunohistochemistry for HIF-1 and VEGF, as well as the incorporation of clinicopathologic data for recorded cases.

References:

1. Beerlage C, Varanat M, Linder K, et al. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii and Bartonella henselae as potential causes of proliferative vascular diseases in animals. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2012; 201: 319-326.

2. Breshears MA, Johnson BJ. Systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis-like syndrome in a steer presumed to be persistently infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Pathol. 2008; 45: 645-649.

3. Dunn KA, Smith KC, Blunden AS. Fatal multisystemic intravascular lesions in a cat. Vet Rec. 1997; 140:128-129.

4. Fuji RN, Patton KM, Steinbach TJ, Schulman FY, Bradley GA, Brown TT, Wilson EA, Summers BA. Feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis: eight cases and literature review. Vet Pathol. 2005; 42: 608-617.

5. Kirke S, Angus B, Kesteven PJL, Calonje E, Simpson N. Localized reactive angioendotheliomatosis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 2006;32:45-47.

6. Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating Intralymphatic Histiocytosis, Intravascular Histiocytosis, and Subtypes of Reactive Angioendotheliomatosis: Review of Clinical and Histologic Features of All Cases Reported to Date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(1):33-39.

7. Rothwell TL, Xu FN, Wills EJ, Middleton DJ, Bow JL, Smith JS, Davies JS: Unusual multisystemic vascular lesions in a cat. Vet Pathol. 1985; 22:510-512.

8. Yamamoto S, Shimoyama Y, Haruyama T. A case of feline systemic reactive angioendotheliomatosis. JFMS Open Rep. DOI: 10.1177/2055116915579684.