Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 7

October 18th, 2017

CASE IV: L17-994 (no label) (JPC 4100736).

Signalment: 4-month-old, female spayed, Domestic shorthair, Felis catus, feline.

History: The kitten presented weak and dehydrated with a packed cell volume (PCV) of 12%. Several other kittens had already died over the past 3-4 months.

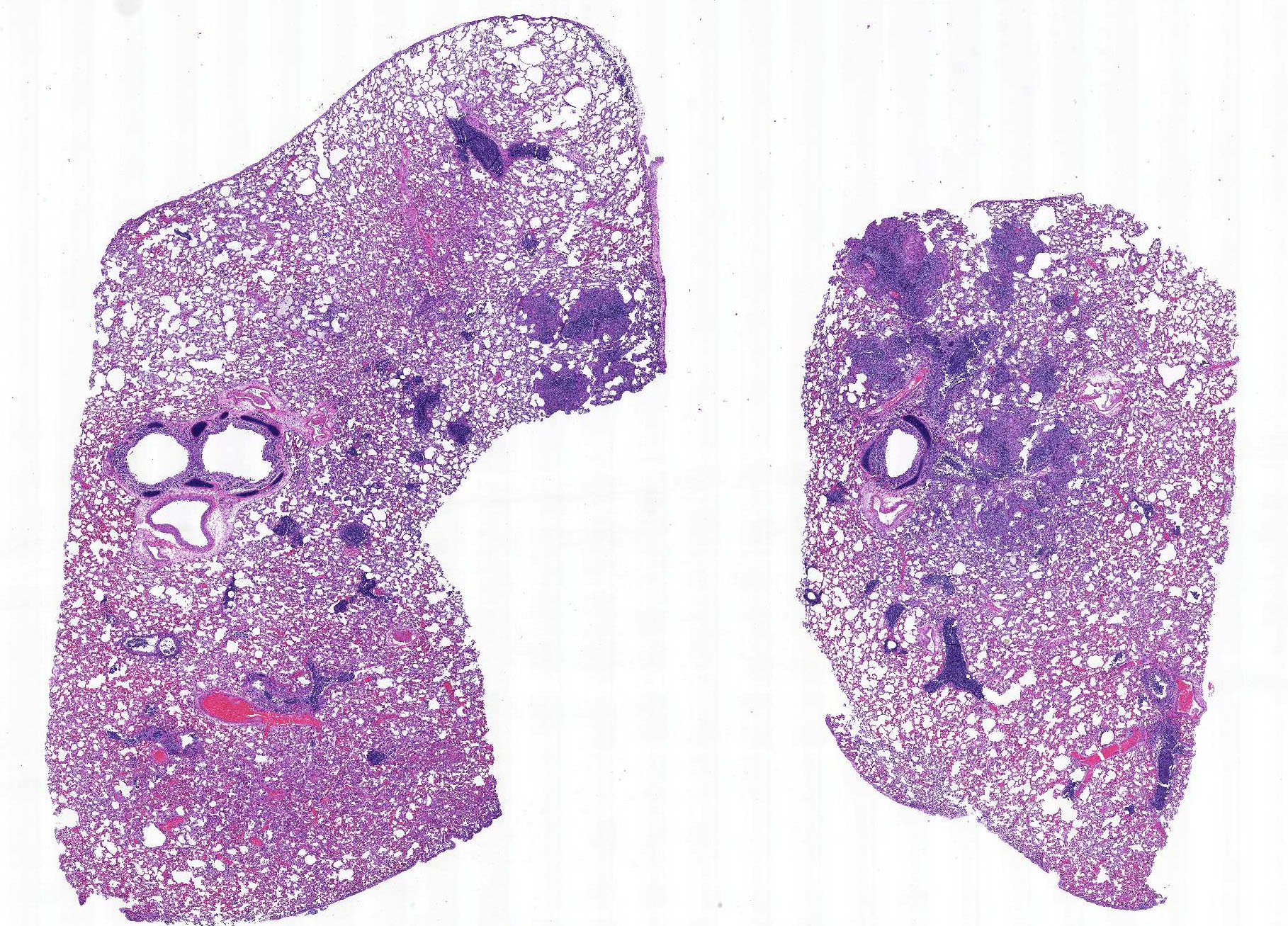

Gross Pathology: A spayed female Domestic shorthair kitten presented for postmortem examination in fair body condition, weighing 1.55 Kg, with minimal postmortem autolysis. Small amount (1 ml) of blood-tinged, yellow, clear fluid was present within the thoracic cavity and moderate amount (approx. 35 ml) of similar fluid mixed with some strands of fibrin was present within the abdominal cavity. Dark brown fluid was present within the upper and lower respiratory tract (interpreted as terminal aspiration). The lungs were mottled pink and red. Minimal amount of dark brown fluid was also present throughout most of the digestive tract, extending from the oral cavity to the small intestines. The colon was distended with abundant dark red to black, soft feces. The gastrointestinal mucosa was unremarkable. The mesenteric lymph nodes were moderately enlarged. The liver had an accentuated lobular pattern and multiple, up to 3 mm diameter, tan to white, smooth foci that were best apparent on the capsular surface. The omentum, ileum, and colon had multiple, 1-2 mm diameter, white, slightly raised nodules on the serosal surface.

Laboratory results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

Bacterial culture (aerobic): Lung: Bordetella sp. (heavy growth)

Special stain (Gram stain): Lung: Moderate numbers of cilia-associated or free gram-negative coccobacilli are within the bronchial and bronchiolar lumen.

Fluorescent antibody test: Lung, liver, intestine, and mesenteric lymph node: Positive for Feline Coronavirus; Intestine, mesenteric lymph node, and spleen: Negative for Feline Parvovirus

Immunohistochemistry for Feline Coronavirus: Lung: Within a focus of peribronchiolar inflammatory cell infiltrate, moderate numbers of macrophages have strong brown (positive) cytoplasmic labeling.

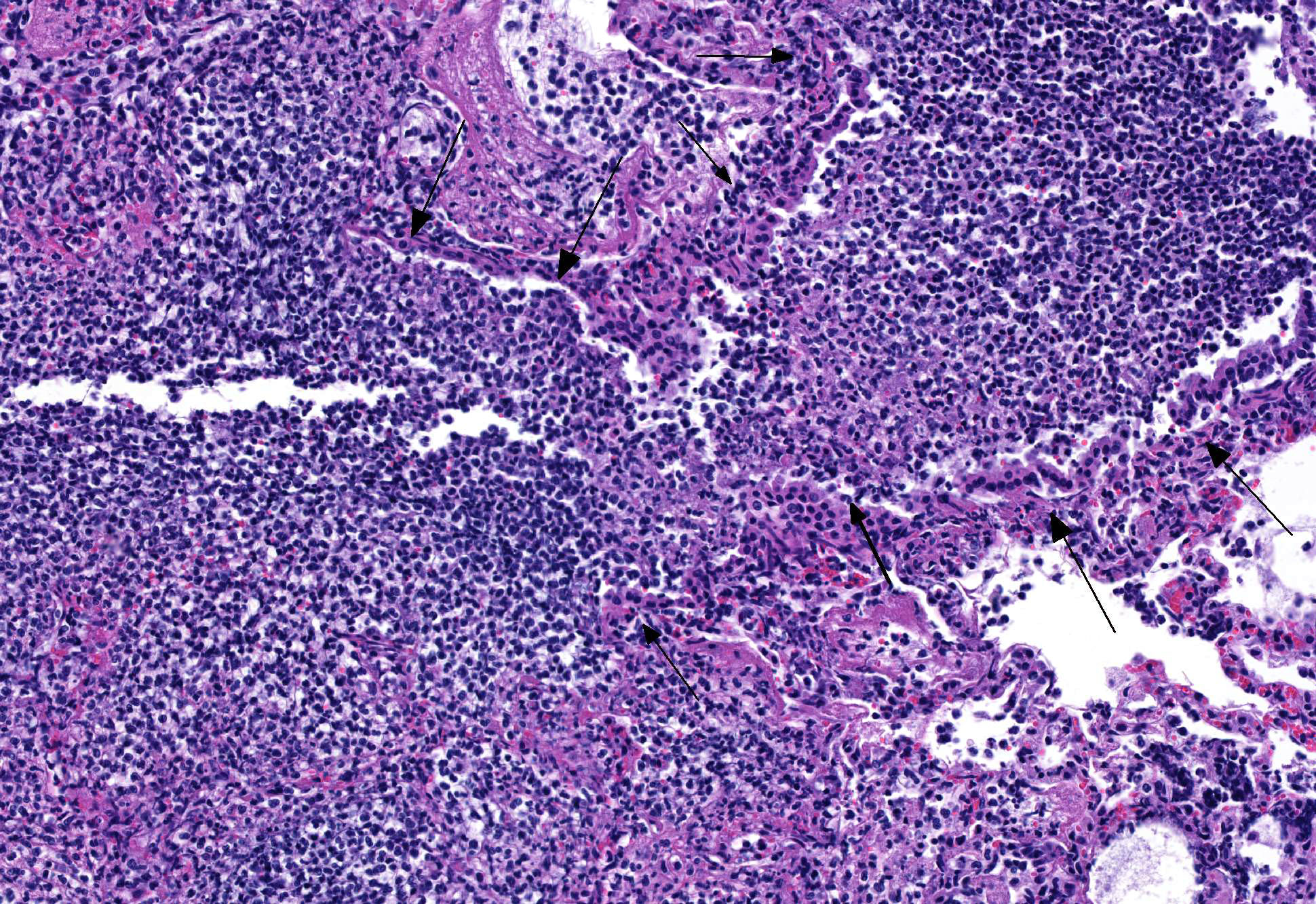

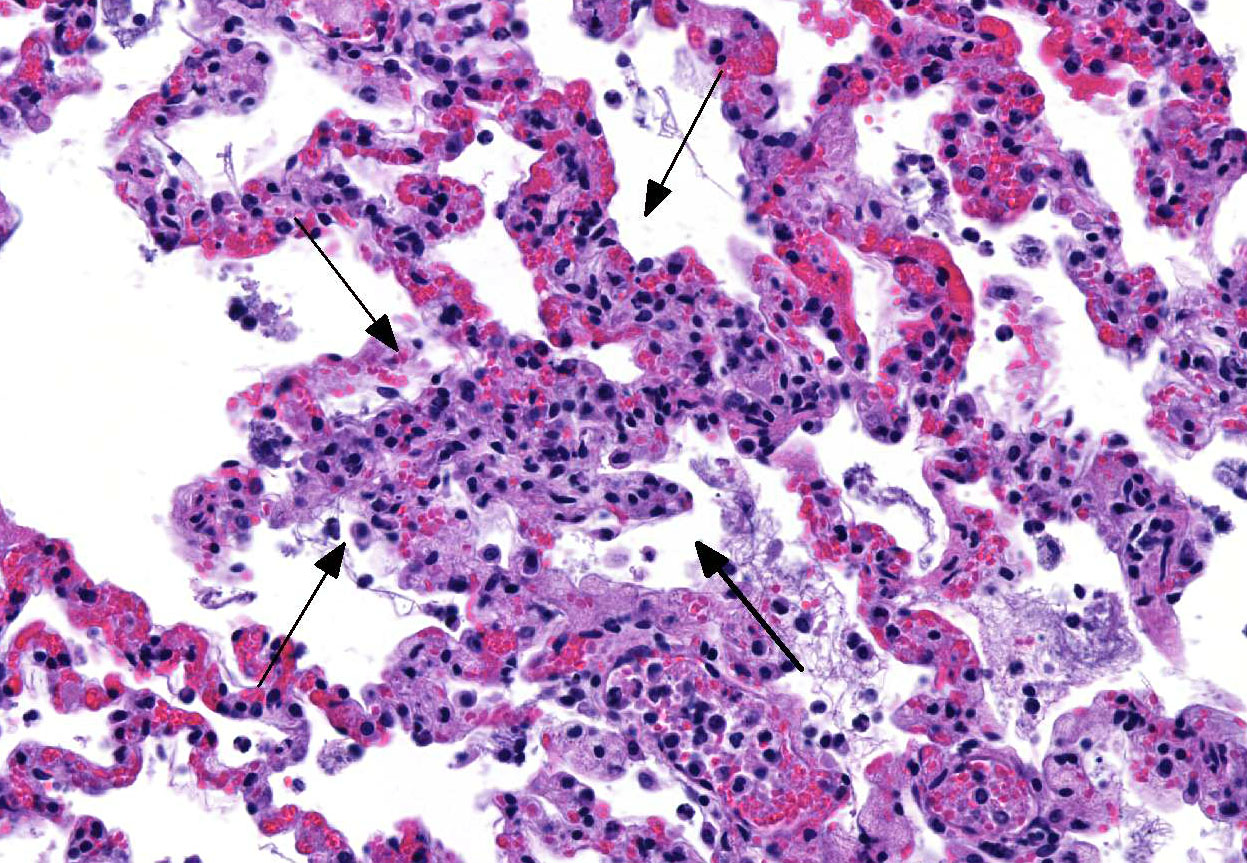

Microscopic Description: Lung: The bronchiolar lumina are filled with abundant viable and degenerate neutrophils interspersed with sloughed epithelial cells. Abundant cilia-associated and free gram-negative coccobacilli are present in the inflamed airways. The alveoli surrounding the inflamed bronchioles are frequently distended by abundant fibrin, neutrophils, and macrophages. Pulmonary vessels are diffusely acutely congested. There is also mild to moderate, diffuse alveolar edema.

Colon, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen (not submitted): In multifocal areas, the serosal surface of the colon, the mesenteric perinodal adipose tissue, and the capsular surface of the liver and spleen are variably expanded by abundant fibrin mixed with numerous viable and degenerate neutrophils and macrophages. In the most severely affected areas, the fibrinous to pyogranulomatous infiltrate extends into the outer longitudinal layer of the tunica muscularis of the colon, the cortical sinuses of the mesenteric lymph nodes, and the hepatic parenchyma.

Contributors Morphologic Diagnoses:

1. Lung: Bronchopneumonia, suppurative, acute, with gram-negative cilia-associated and free bacteria.

2. Lung: Pneumonia, fibrinosuppurative and histiocytic, multifocal, with intrahistiocytic feline coronaviral antigen.

3. Intestine, mesenteric lymph node, liver, and spleen (not submitted): Inflammation, fibrinosuppurative to pyogranulomatous.

Contributors Comment: Bordetella bronchiseptica pneumonia is particularly important in kittens <12 weeks of age1 and in puppies between 7-35 weeks of age2 due to a greater severity of clinical disease that ensues at this age with a potential of fatal outcome. B. bronchiseptica is also important because of its zoonotic potential, particularly for people with immunosuppression.3 A well-recognized virulence attribute of this pathogen is its adherence to cilia.4 This adherence is determined by Bvg-regulated expression of filamentous hemagglutinin and pertactin, fimbriae, as well as by adenylate cyclase-hemolysin toxin.5 The histologic detection of bronchial and bronchiolar cilia-associated bacteria is a significant feature of the diagnosis of B. bronchiseptica as a cause of bronchopneumonia.6 Along these lines, we detected cilia-associated and free gram-negative bacteria in the lower airways in the histologic lung sections of this kitten. This, combined with the heavy growth of Bordetella sp. from the lung, confirms B. bronchiseptica as the primary cause of the respiratory disease in this case.

Although the lung lesions in this case were largely attributed to the Bordetella sp. bronchopneumonia, the fibrinosuppurative and histiocytic inflammatory alterations in the surrounding alveoli together with the immunohistochemical detection of FCoV antigen in multiple macrophages in one area suggests that there was at least partial contribution of this virus to the respiratory disease of this kitten.

Fibrinosuppurative to pyogranulomatous inflammation associated with feline coronavirus antigen detected by fluorescent antibody testing was also present in several other tissues of this kitten, namely the colon, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver and spleen, consistent with the diagnosis of Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP). FIP is a fatal systemic disease of wild and domestic felids caused by feline coronavirus (FCoV), a member of the family Coronaviridae and genus Coronavirus, an enveloped, positive-strand RNA virus that spreads via fecal-oral route. Characteristic lesions of FIP include granulomatous phlebitis, fibrinous to granulomatous serositis, and pyogranulomatous inflammation of multiple organs.7 Cats that present with FIP are usually less than 2 years of age and come from a multi-cat environment.8 This was true in our case as well, in which the kitten was only 4 months old and came from a multi-cat environment where other kittens had already died. Cats with FIP are lymphopenic,7 which may have predisposed this kitten to the respiratory bordetellosis. The clinically noted anemia was attributed to gastric bleeding and melena, although gastric erosions and/or ulcers were not apparent on gross and histologic examination.

JPC Diagnosis: Lung: Bronchopneumonia, necrosuppurative, diffuse, marked, with diffuse fibrinous interstitial pneumonia, vascular thrombosis, and numerous cilia-associated bacteria, Domestic shorthair (Felis catus), feline.

Conference Comment: Conference participants agreed with the contributors presupposition that the majority of the lesions in the lung are caused by Bordetella bronchiseptica (which was identified lined up parallel to cilia within large airways using Grams stain). In the sections distributed to the participants, there are no vascular or other lesions that could be directly atrributable to coronavirus infection, but the participants discussed that immunosuppression by FIPV predisposed this kitten to developing a respiratory bacterial infection.

Bordetella bronchiseptica is a normal commensal in the upper respiratory tract of most domestic animals but can act as a primary pathogen resulting in tracheobronchitis which can progress to pneumonia in more chronic cases. In pigs, it is the primary cause of nonprogressive atrophic rhinitis resulting in mild nasal discharge and sneezing. Certain strains of B. bronchiseptica can adhere to nasal cilia and tonsilar epithelium and produce toxins that cause distortion and loss of cilia, submucosal edema, and resorption of the turbinate bone. This process is completely reversible, but predisposes the animal to developing progressive atrophic rhinitis caused by Pasteurella multocida type D. This gram negative bacterium produces a cytotoxin, dermonecrotic toxin (encoded on the toxA gene), that results in nonreversible changes to the snout. Similar lesions occur in the epithelium and submucosa with one key difference: this cytotoxin causes proliferation of nearby fibroblasts which secrete mediators that induce hyperplasia and increased function of osteoclasts (reabsorbing bone) and decreased function of osteoblasts (reduced formation of bone).2

Expression of virulence factors mediated by the Bordetella virulence gene (bvg) operon allows for extensive variability among strains of B. bronchiseptica. The bvg operon encodes the following: (1) proteins necessary for attachment to host cells (adhesive proteins filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin, fimbriae which aide in adhesion to ciliated cells) and (2) proteins that allow for bacterial survival (iron scavenging, motility mediation, urease and phosphatase activity). However, the most important contributors to the pathogenicity of B. bronchiseptica is the secreted adenylate cyclase toxin (hemolysin) which is of the RTX family related to Mannheimia haemolytica leukotoxin and Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae Apx toxin. This potent toxin forms pores in target cells, generally leukocytes, to allow transfer of the adenylate cyclase component, resulting in increased cyclic AMP production, which impairs phagocytosis and oxidative burst and leads to cell death forming the characteristic oat cells seen microscopically composed of streaming nuclear debris.2

Louisiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory

http://www1.vetmed.lsu.edu/laddl/index.html

References:

1. Anderton TL, Maskell DJ, Preston A. Ciliostasis is a key early event during colonization of canine tracheal tissue by Bordetella bronchiseptica. Microbiology. 2004; 150: 2843-2855.

2. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. New York, NY: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:533, 578-579, 589.

3. Edwards JA, Groathouse NA, Boitano S. Bordetella bronchiseptica adherence to cilia is mediated by multiple adhesin factors and blocked by surfactant protein A. Infect Immun. 2005; 73: 36183626.

4. Kipar A, Meli ML: Feline infectious peritonitis: still an enigma? Vet Pathol. 2014; 51: 505-526.

5. Radhakrishnan A, Drobatz KJ, Culp WT, King LG. Community-acquired infectious pneumonia in puppies: 65 cases (19932002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2007; 230: 14931497.

6. Taha-Abdelaziz K, Bassel LL, Harness ML, Clark ME, Register KB, Caswell JL. Cilia-associated bacteria in fatal Bordetella bronchiseptica pneumonia of dogs and cats. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2016; 4: 369-376

7. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system: Feline infectious peritonitis. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 2. 6th ed. New York, NY: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:253-255.

8. Welsh RD. Bordetella bronchiseptica infections in cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1996; 32: 153158.

9. Yacoub AT, Katayama M, Tran J, Zadikany R, Kandula M, Greene J. Bordetella bronchiseptica in the immunosuppressed populationa case series and review. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014; 6:e2014031.