Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 22

April 18th, 2018

CASE III: 15-23253 (JPC 4066861).

Signalment: 7-year-old, spayed, female, Bullmastiff (Canis familiaris), canine.

History: A 7 year old spayed female Mastiff was referred to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals Emergency Service for evaluation of hemoabdomen and a two day history of weakness, lethargy, and in appetence. On presentation, the patient was febrile with tachycardia and tachypnea. Abdominal ultrasound and abdominocentesis confirmed a hemorrhagic effusion. Platelet numbers were moderately decreased, and coagulation parameters were within normal limits. The patient also had a one month history of an ulcerated mass on the right lateral thigh that had been unresponsive to treatment with antimicrobials.

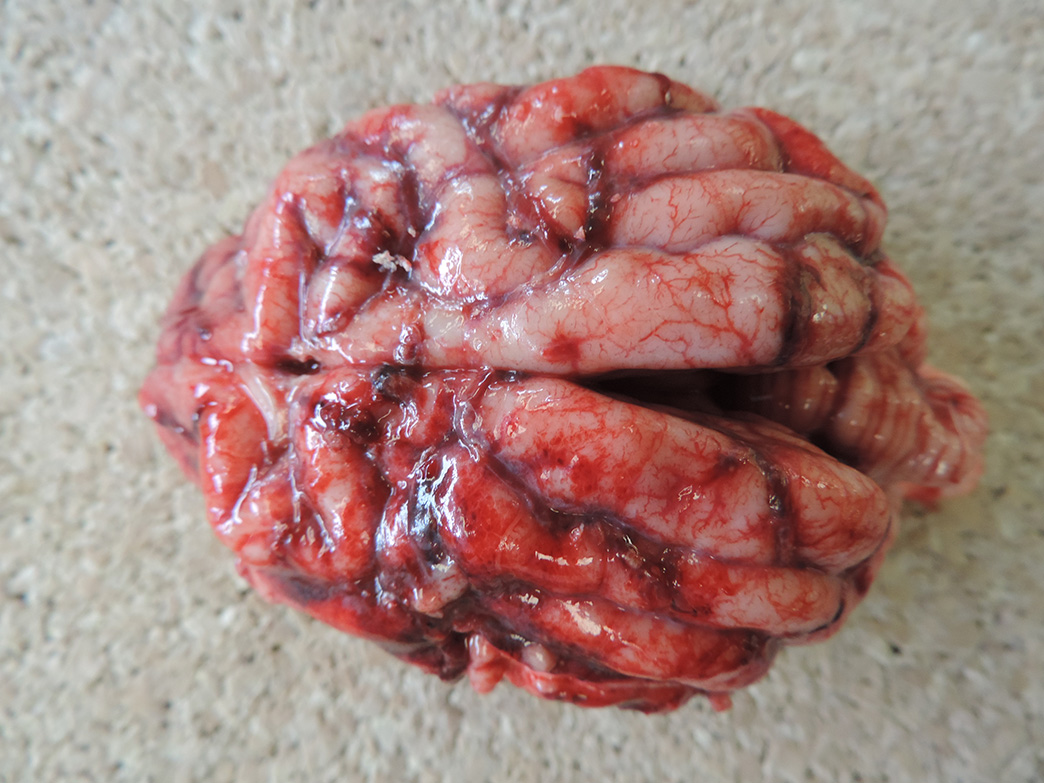

While hospitalized the patient developed neurologic signs, including a vestibular episode with nystagmus and ataxia, circling, head-pressing, and knuckling. Her neurologic signs progressed to tetraplegia, and she became obtunded. The patient’s condition further declined, and she died in the hospital.

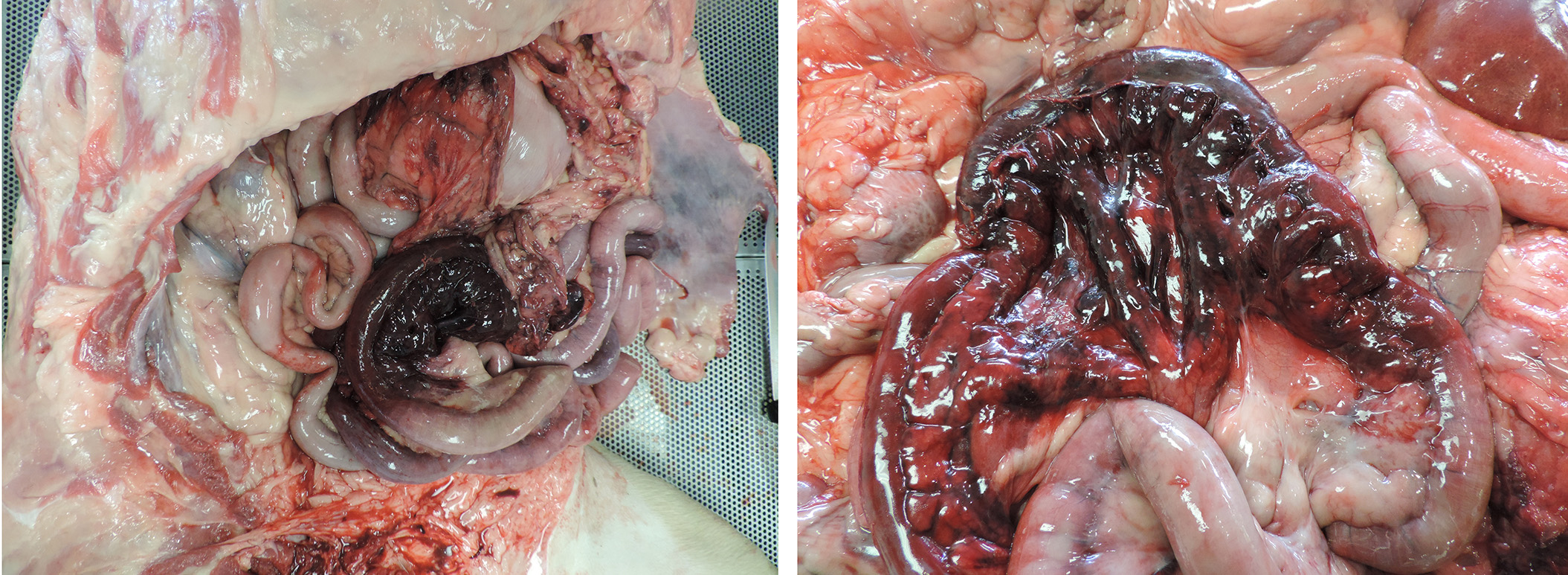

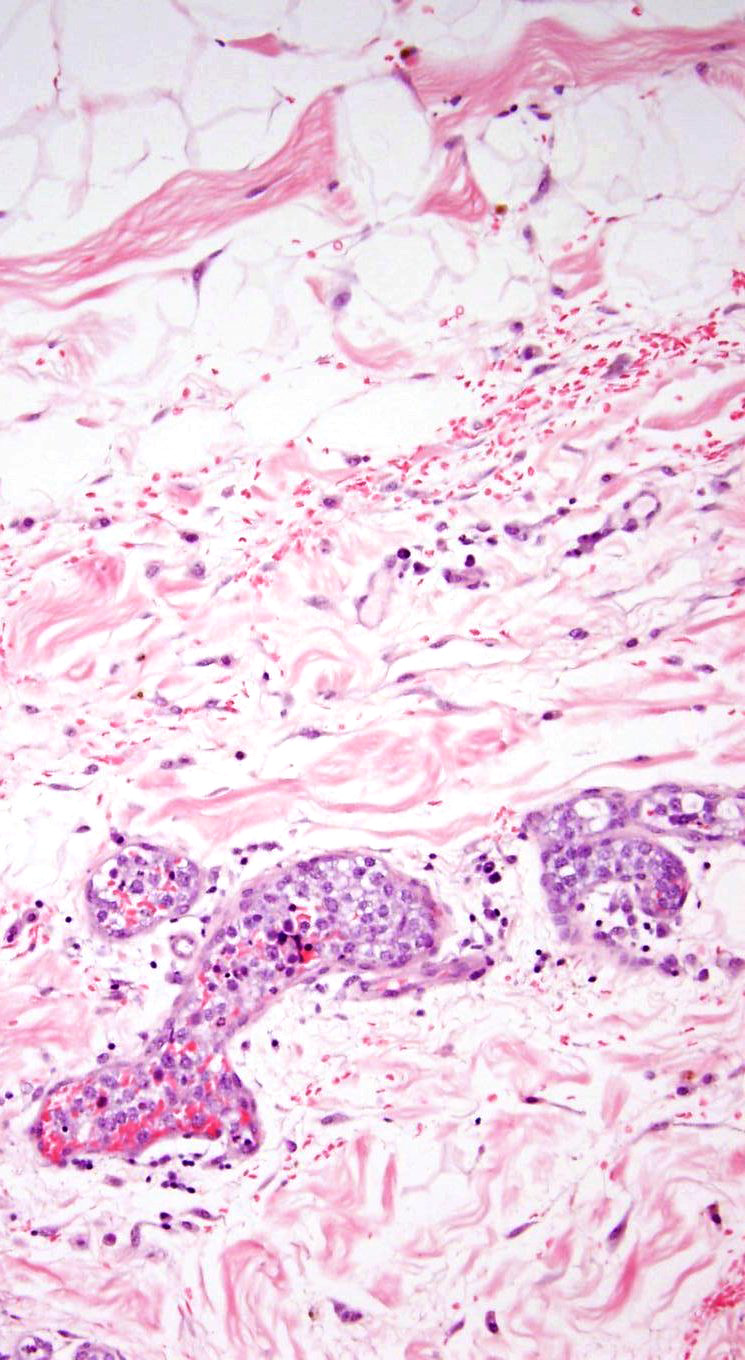

Gross Pathology: Gross examination confirmed hemoabdomen and focal cutaneous ulceration at the lateral right thigh. Examination further revealed multiple sites of acute infarction and hemorrhage in the meninges and cerebrum, small intestine, lung, and a mesenteric lymph node. More chronic sites of infarction were found in the kidney and myocardium.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): None provided.

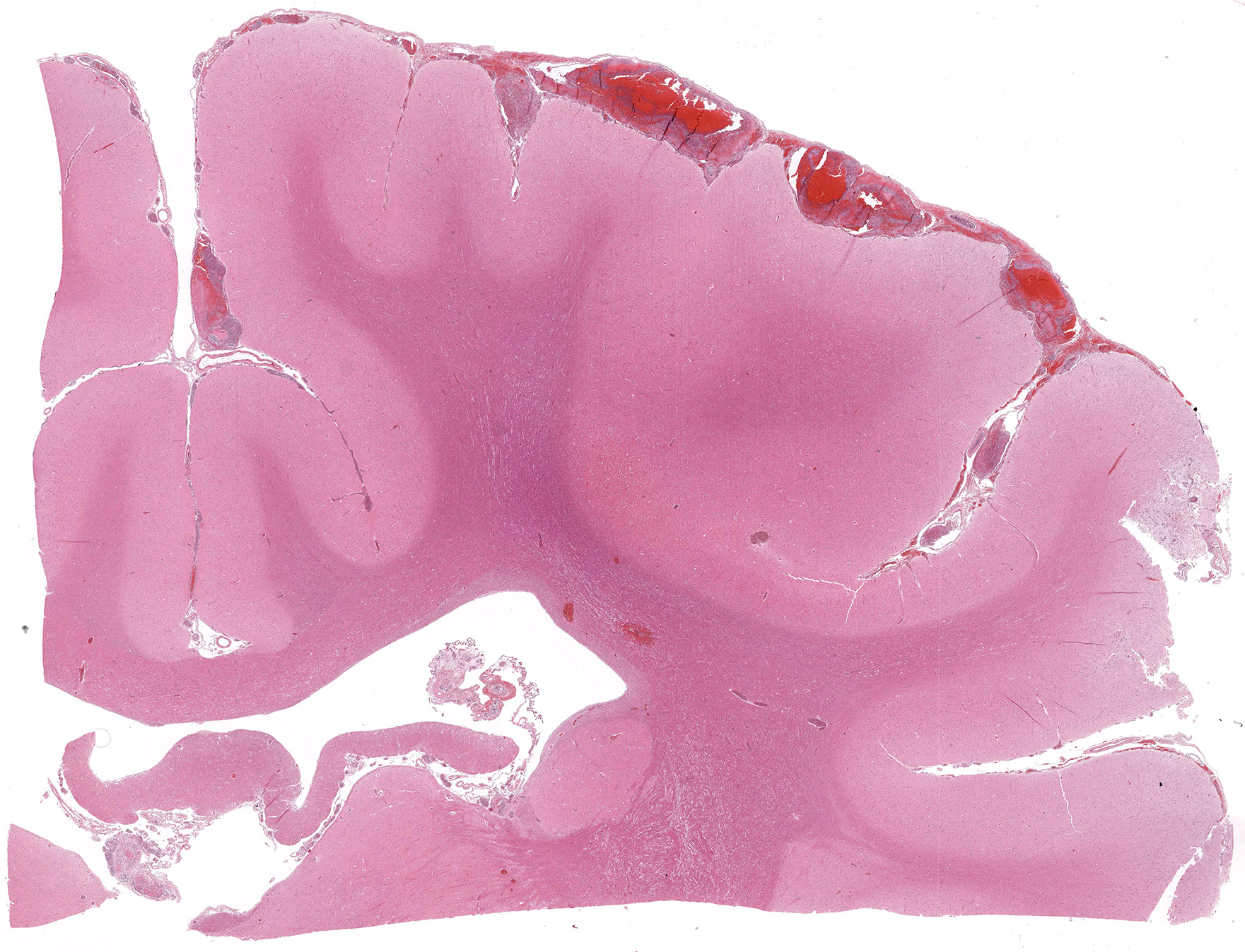

Microscopic Description:

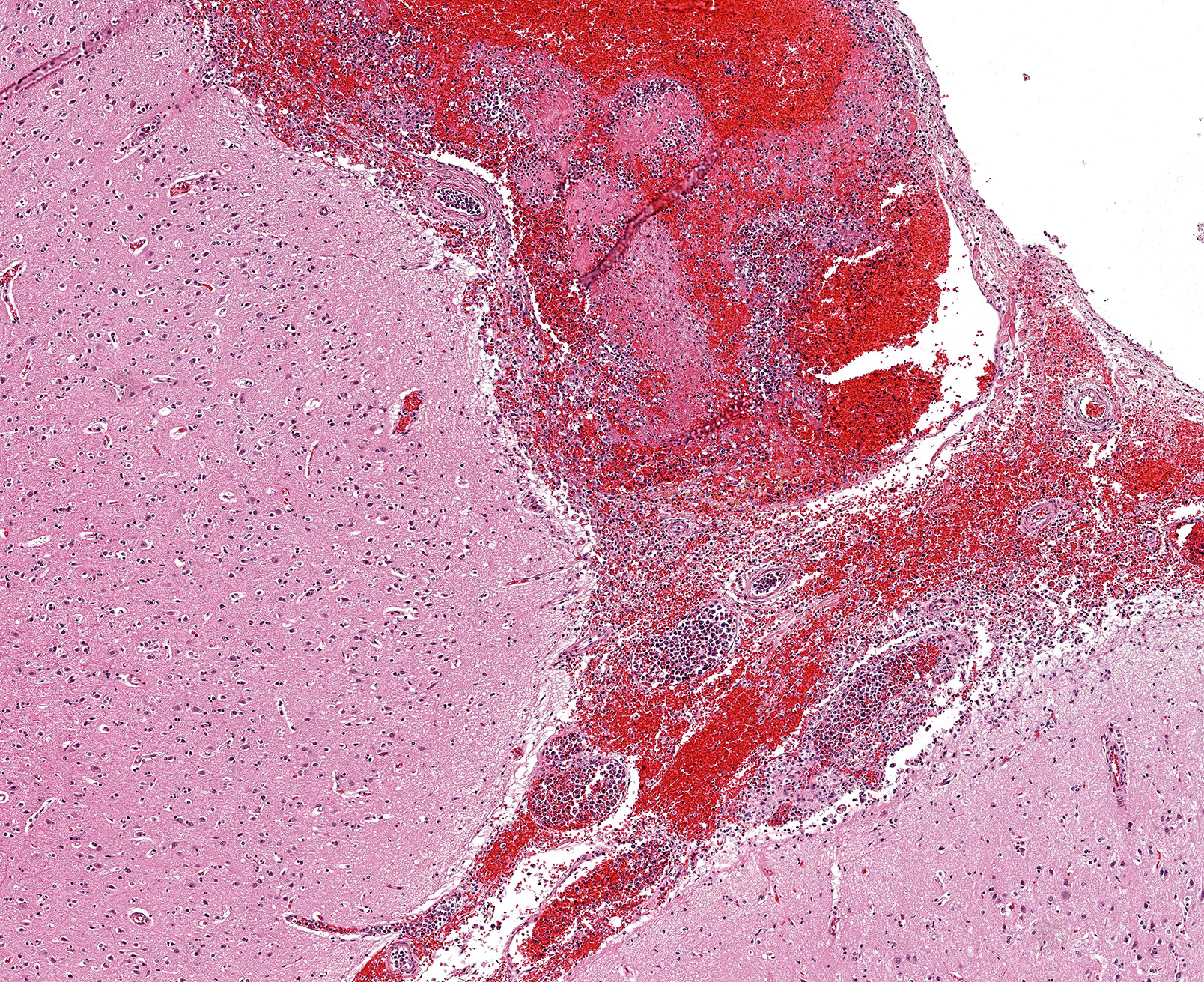

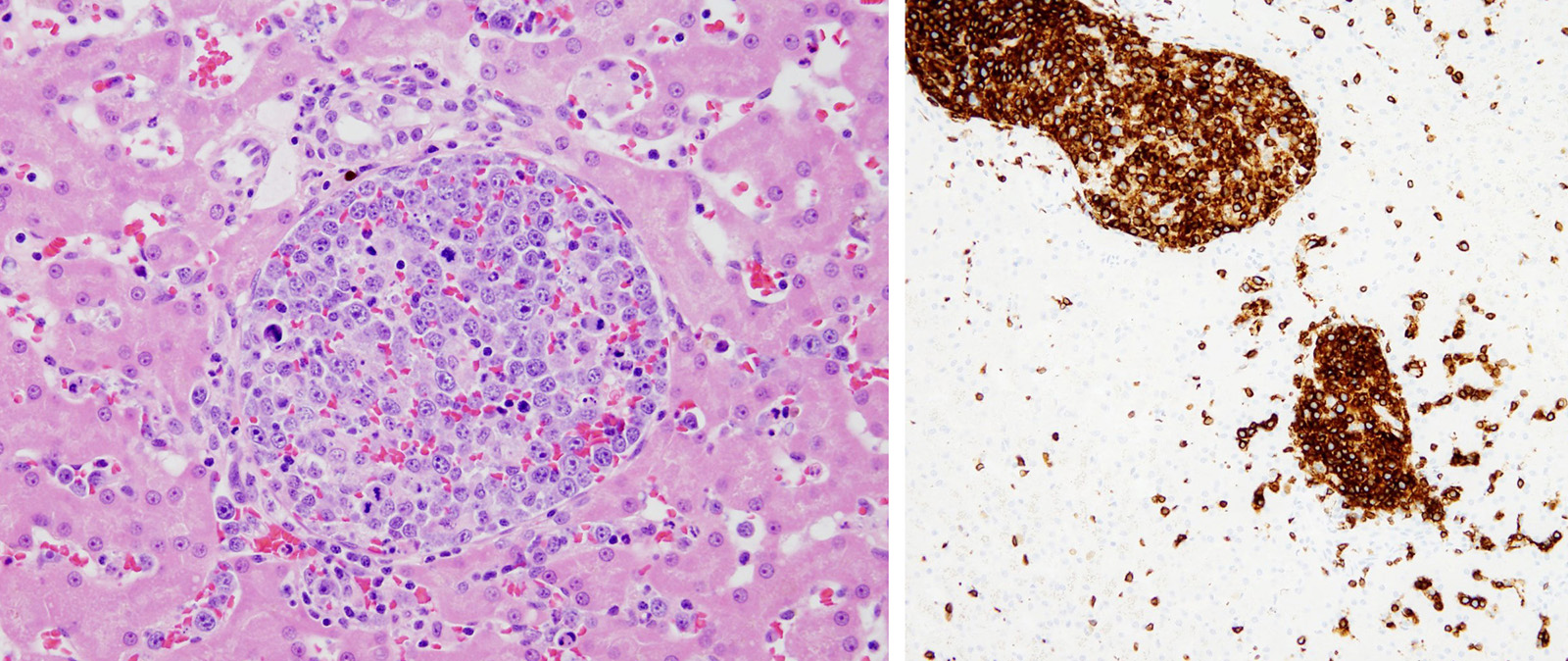

The submitted slide includes a section of liver. Distending portal and central veins and expanding sinusoids are sheets and clusters of intravascular neoplastic cells. Neoplastic cells are round with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Nuclei are up to twice the diameter of a neutrophil and have distinct cell margins, scant amphophilic to pale basophilic cytoplasm, and an often eccentric, round or indented nucleus with coarsely clumped chromatin and 1-3 magenta nucleoli. There is marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and up to 4 mitotic figures per high magnification (400x) field. There are scattered apoptotic neoplastic cells. Sinusoids also contain increased numbers of circulating neutrophils and lymphocytes. Hepatic cords are thin with mildly dilated sinusoidal spaces (atrophy). Portal and central vein lymphatics are occasionally dilated.

Immunohistochemistry revealed positive reactivity for CD3, consistent with a T cell origin. Similar intravascular neoplastic populations were observed in the lung, heart, kidney, jejunal mesentery, pancreas, mesenteric lymph node, skin, and brain, often associated with thrombosis and infarction.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Intravascular lymphoma, large T cell

Contributor’s Comment: Intravascular lymphoma (IVL) is a rare large-cell lymphoma, defined by its confinement within blood vessel lumina in the absence of leukemia or a primary extravascular mass. Typical clinical and pathologic features are related to vascular occlusion, injury, and fibrin thrombosis, often with central nervous system signs. In a review of 17 cases of IVL in dogs, predominant clinical signs included spinal cord ataxia, seizures, vestibular disease, lethargy, diarrhea, and fever.4 Skin involvement was apparent in one of the cases.4 IVL accounted for the spectrum of clinical findings in this dog, including the neurologic signs (due to cerebral thrombosis and infarction), hemoabdomen (small intestinal infarction), and ulcerative dermatitis. No extravascular lymphomatous masses were found at necropsy, and ante-mortem blood work was not consistent with leukemia.

Intravascular lymphoma was first described in the dog as angioendotheliomatosis, under the assumption that the neoplastic cells were derived from the endothelium, but subsequent immunohistochemical data determined the lymphocyte-derivation.4,6,7 Refinement of understanding of intravascular lymphoma in dogs was supported by work on immunohistochemical and ultrastructural data on similar human neoplasms.6 While the majority of human cases are derived from B cells, most reported intravascular lymphomas in dogs are derived from T cells or non-B, non-T lymphocytes.2,4,8 Human and canine cases show a similar predilection for nervous system involvement, but cutaneous presentation appears to be more common in humans.4

Neoplastic lymphocytes are generally most abundant in capillaries and small to medium veins, but also appear in smaller numbers within arteries.4 The mechanism for the selective intravascular growth of IVL is unknown, but defective cell-to-cell adhesion between the neoplastic lymphocytes and endothelial cells has been proposed.1,5

JPC Diagnosis: Liver, veins, arteries, and sinusoids: Intravascular lymphoma, multifocal, Bull mastiff (Canis familiaris), canine.

Conference Comment: Angiotropic intravascular lymphoma, previously also referred to as malignant angioendotheliomatosis, is a rare tumor in humans and dogs, and has been reported a cat. Microscopically, it is characterized by a proliferation of neoplastic lymphocytes within the lumen and wall of blood vessels with no primary extravascular mass. In most human cases, these cells have been identified as B-cells, but in canine and feline cases, the majority are of T-cell origin.3,4 Clinically, most of these cases present with neurologic signs and microscopically neoplastic cells are seen occluding cerebral arteries and veins. The vessels of the lungs are also commonly affected. In the affected cat,3 there was severe involvement of the kidneys and cerebrum with absence of neoplastic cells in other visceral organs. Diagnosis usually follows the onset of neurologic signs and is typically postmortem. There are no neoplastic cells identified in routine blood samples. In humans, even with chemotherapy, prognosis is poor. There is no treatment data in domestic animals.3

The moderator shared a case that she had also of a female Bullmastiff that had intravascular lymphoma who presented with neurologic signs, acute renal failure, antibiotic-resistant urinary tract infection, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia. She then graciously reviewed images of the case and features of the entity.

Contributing Institution:

Anatomic Pathology

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine

http://www.vet.cornell.edu/biosci/pathology/

References:

- Jalkanen S, Aho R, Kallajoki M et al. Lymphocyte homing receptors and adhesion molecules in intravascular malignant lymphomatosis. Int J Cancer. 1989;44:777–782.

- Lane LV, Allison RW, Rizzi TR et al. Canine intravascular lymphoma with overt leukemia. Vet Clin Pathol. 2012;41:84–91.

- LaPointe JM, Higgins RJ, Kortz GD, Bailey CS, Moore PF. Intravascular malignant T-cell lymphoma (malignant angioendotheliomatosis) in a cat. Vet Pathol. 1997;34(3):247-250.

- McDonough SP, Van Winkle TJ, Valentine BA, et al. Clinciopathological and immunophenotypical features of canine intravascular lymphoma (malignant angioendotheliomatosis). J Comp Path. 2002;126:277–288.

- Ponzoni M, Arrigoni G, Gould VE et al. Lack of CD 29 (β1 integrin) and CD 54 (ICAM-1) adhesion molecules in intravascular lymphomatosis. Hum Pathol.2000;31:200–226.

- Sheibani K, Battifora H, Winberg CD et al. Further evidence that “malignant angioendotheliomatosis” is an angiotropic large-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:943–948.

- Summers BA, deLahunta A. Cerebral angioendotheliomatosis in a dog. Acta Neuropathologica. 1985;68:10–14.

- Zuckerman D, Seliem R, Hochberg E. Intravascular lymphoma: the oncologist’s “great imitator”. The Oncologist. 2006;11:496–502.