CONFERENCE 24, CASE 2

Signalment:

3-week-old male Bulldog (Canis familiaris)

History:

The puppy was born by caesarean section and was from a litter of eight. At 18 days old it was found shaking, anorexic and lethargic and was treated empirically with amoxicillin and dexamethasone. The puppy deteriorated and within 48 hours was hospitalized and placed in an oxygen tent. A serosanguinous nasal discharge and regurgitation of milk from the nose and mouth were present. The puppy was the second of the litter to die; a third puppy was unwell at the time this puppy was presented for postmortem examination.

Gross Pathology:

The 3-week-old male Bulldog puppy was in only adequate body condition (total body weight 735g). On external examination, a moderate amount of white fluid (milk) was present in the nasal passages. On internal examination, there were multifocal to coalescing petechial to ecchymotic hemorrhages throughout the renal cortex that on cut surface extended into the renal parenchyma. The liver was diffusely pale and had multifocal petechial hemorrhages, and multifocal 1 mm pitted areas on the capsular surface. No other gross lesions were present elsewhere.

Microscopic Description:

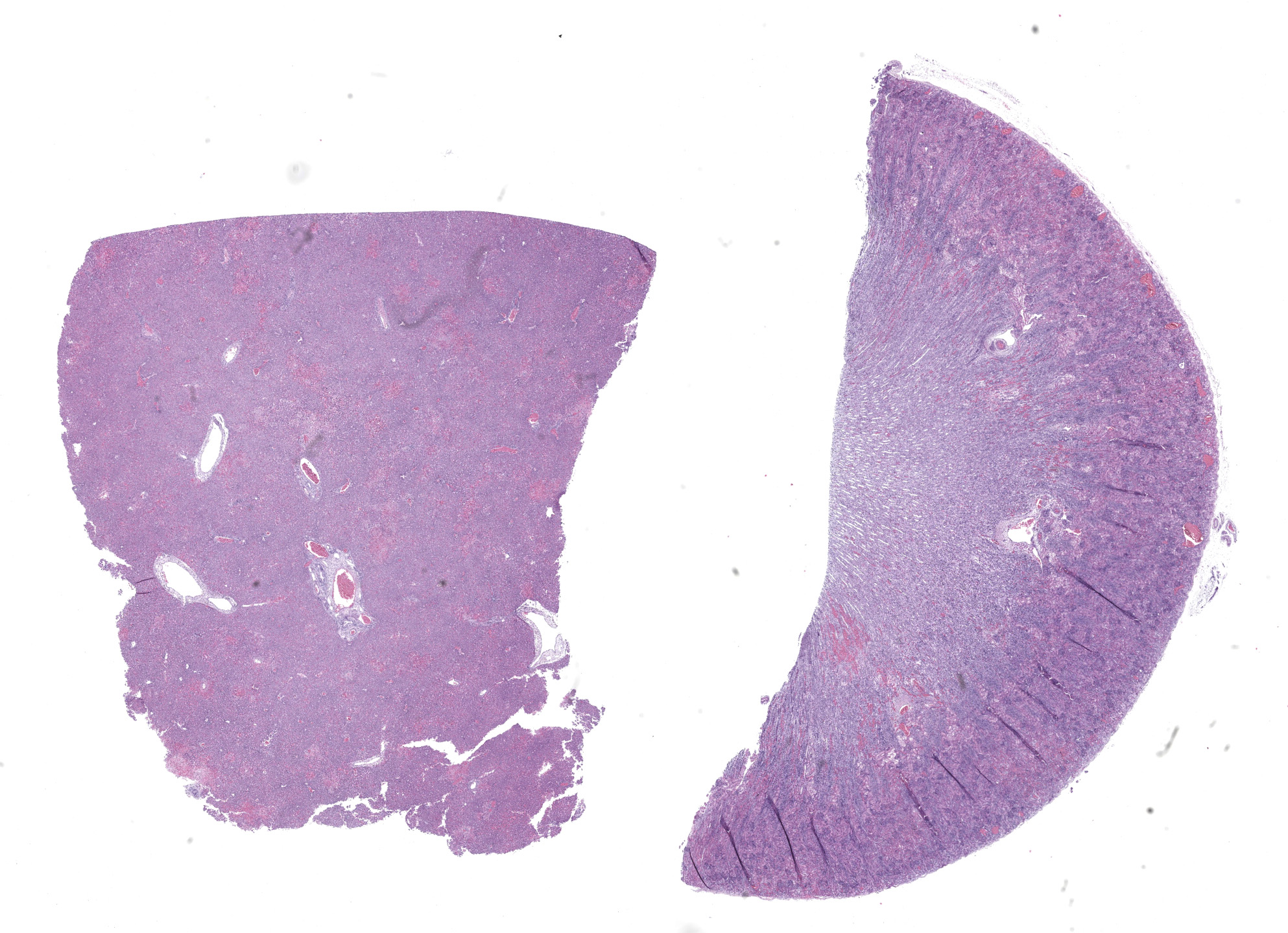

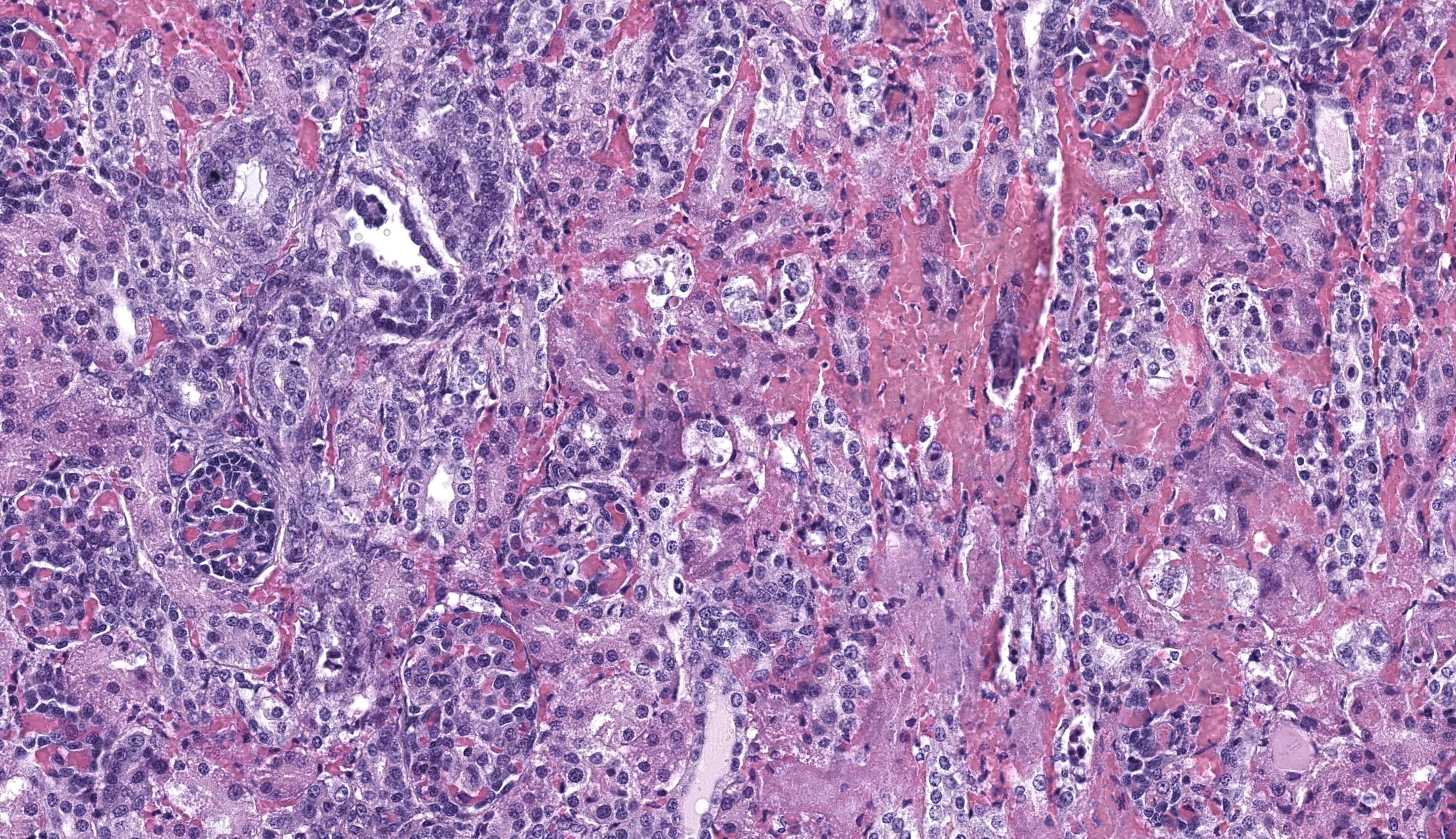

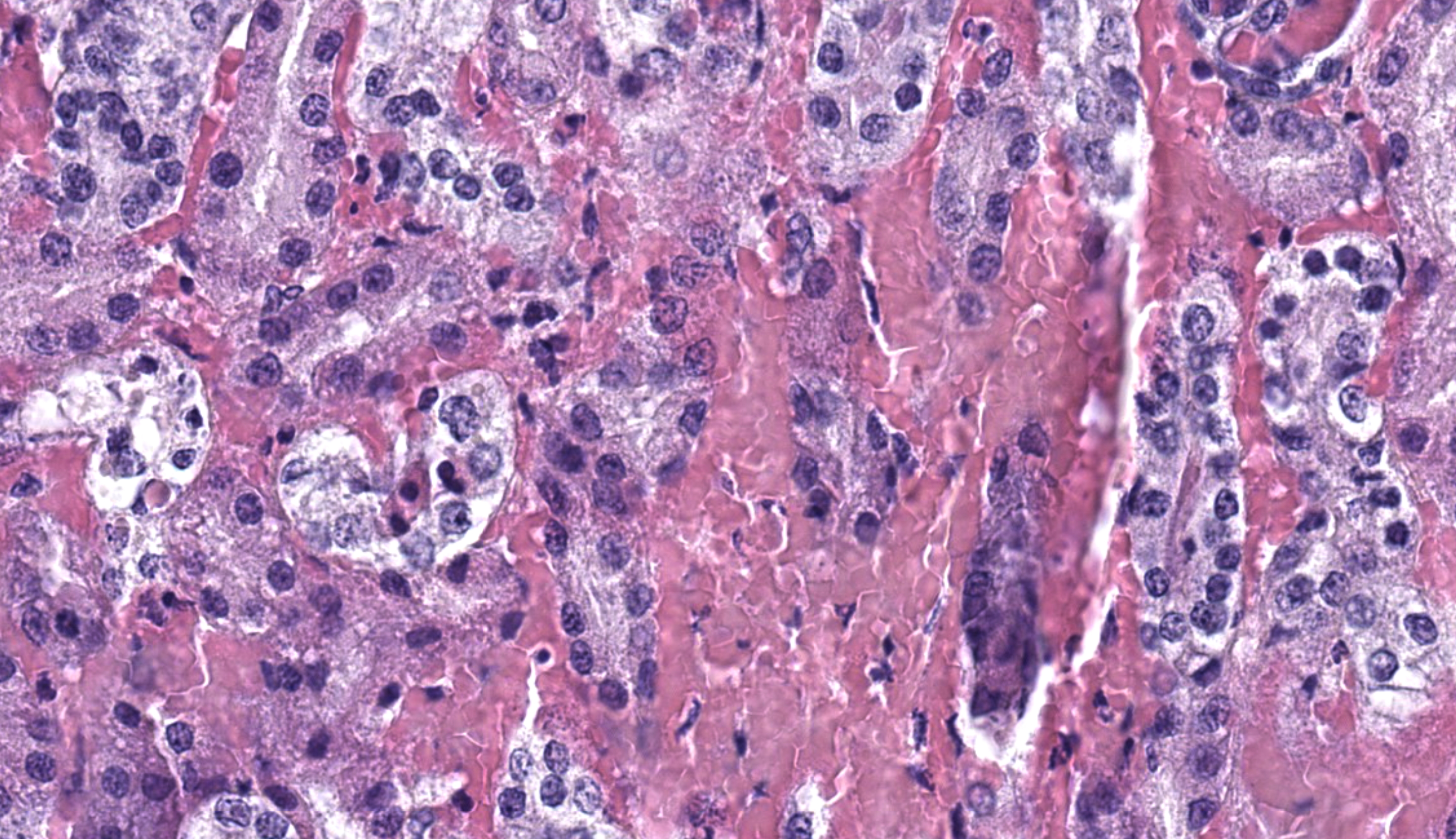

Kidney: Affecting approximately 30% of the renal parenchyma, with lesions predominantly localized in the cortex, are multifocal randomly distributed foci of coagulative necrosis characterized by tinctorial aberrations and retention of cellular architecture, with accumulations of cellular and karyorrhectic debris admixed with haemorrhage, fibrin and edema. Renal tubular epithelial cells within these areas are degenerate with swollen, pale and vacuolated cytoplasm, or necrotic with hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclear pyknosis and occasional sloughing into luminal spaces. Rare 2-4 um eosinophilic, intranuclear viral inclusions are present within renal tubular epithelial cells. Multifocally, glomeruli rarely display segmental necrosis, characterized by hypereosinophilia, loss of cellular detail and the presence of karyorrhectic debris. Visceral and parietal epithelium are hypertrophied in affected glomeruli.

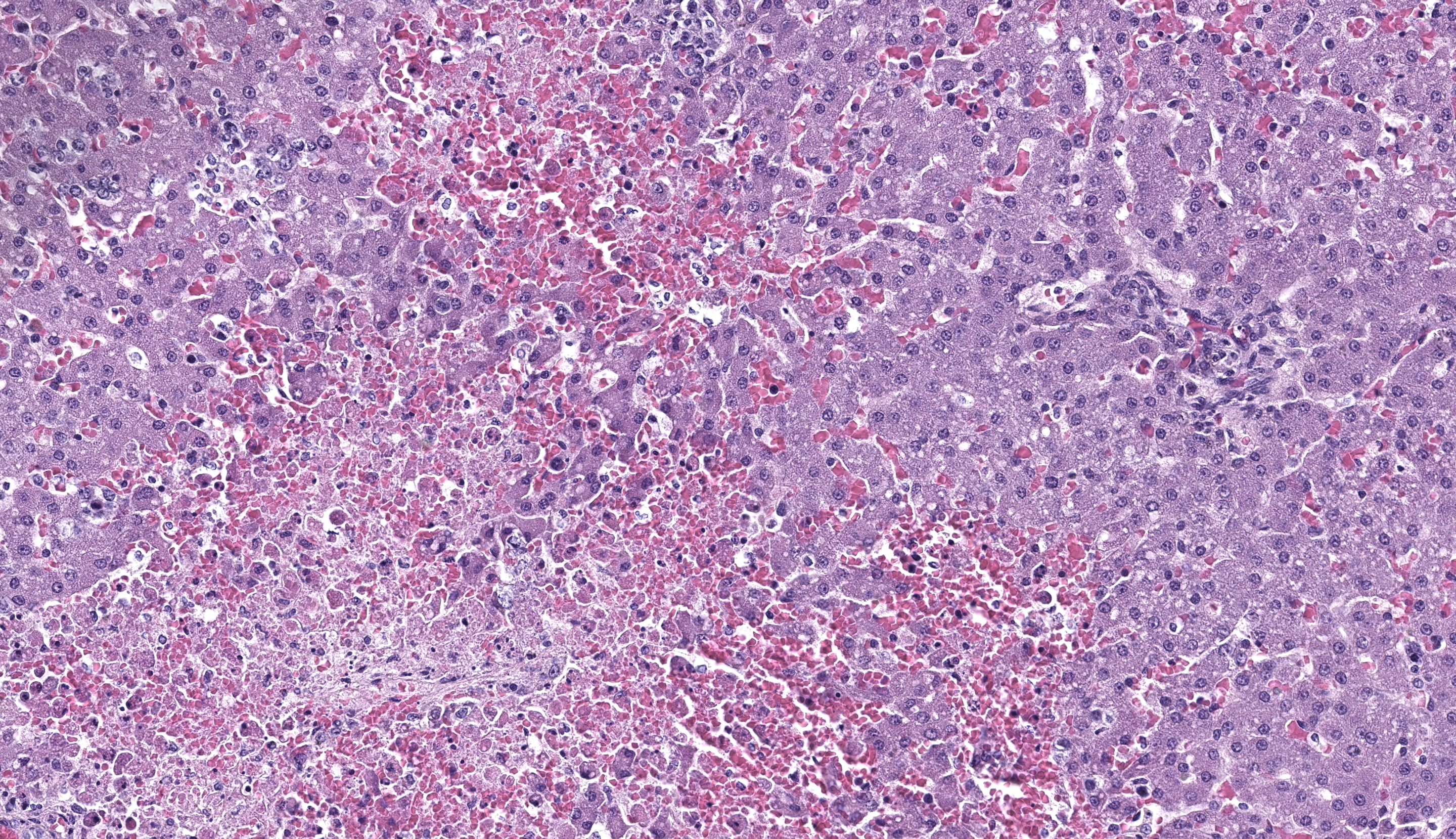

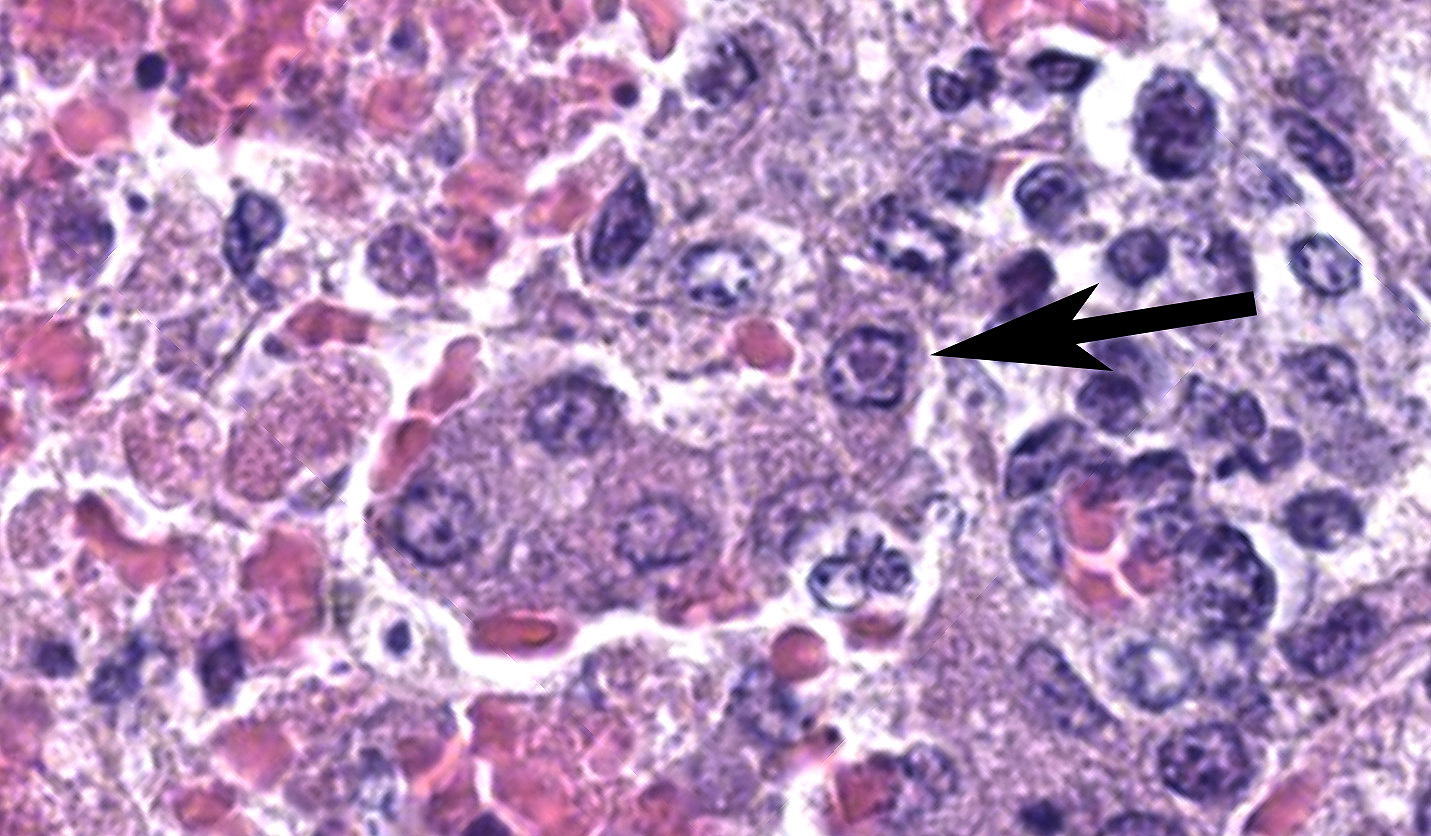

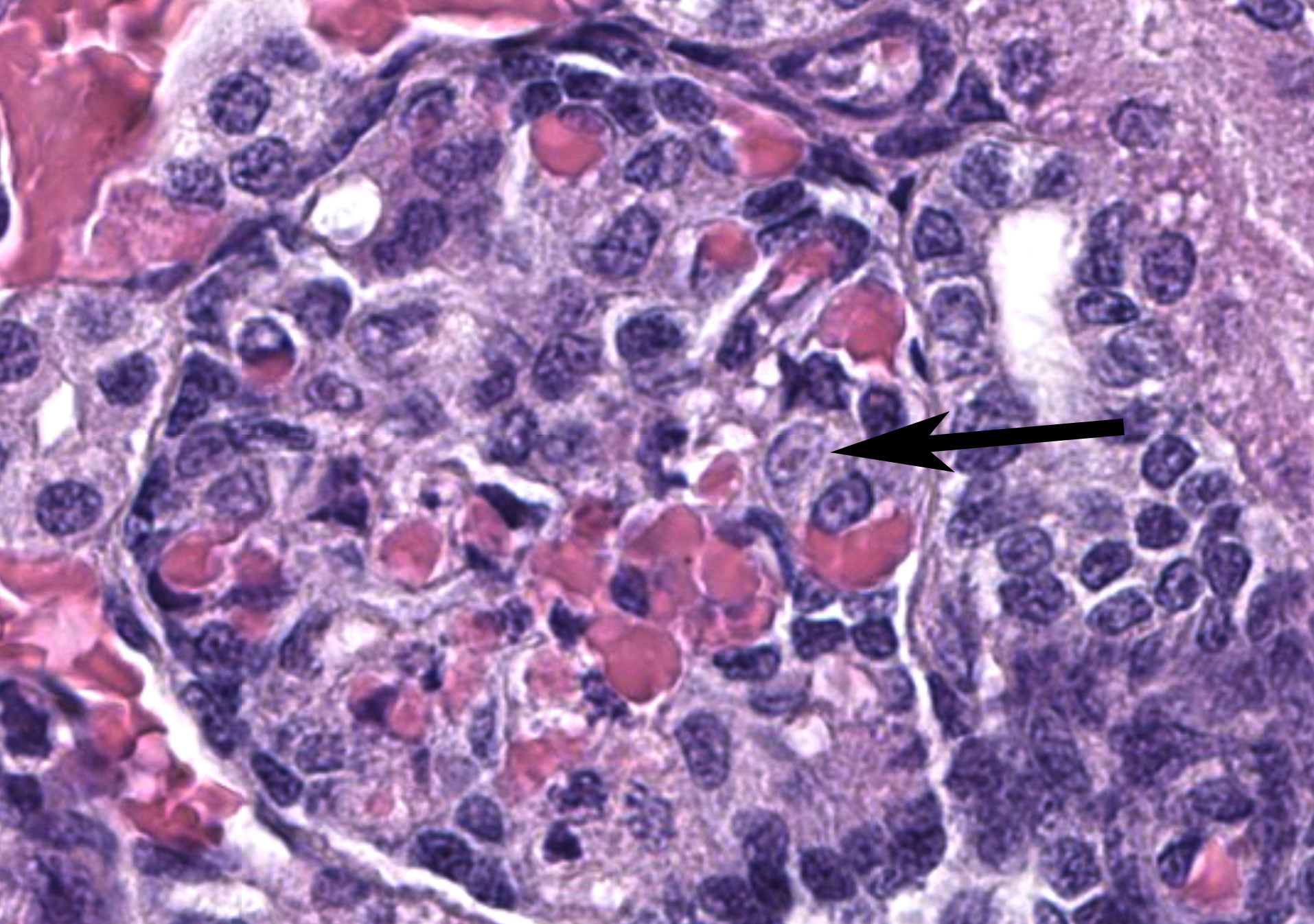

Liver: Within the liver, there is multifocal random hepatocellular necrosis, characterized by loss of normal architecture and replacement by cellular and karyorrhectic debris, hemorrhage and low numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. Rarely, hepatocytes adjacent to areas of necrosis have 2-4 um, eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusion bodies, which are surrounded by a clear halo and peripheralize nuclear chromatin. Periportal areas are mildly expanded by edema and low numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. Diffusely, small and medium arteriolar walls are moderately expanded by edema, with endothelial cells showing a spectrum of cell degeneration and necrosis including nuclear and cytoplasmic swelling, pyknosis, karyorrhexis and karyolysis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Kidney: Severe, acute, multifocal, necrohemorrhagic nephritis with rare epithelial intranuclear viral inclusions.

Liver: Severe, acute, multifocal random, necrohemorrhagic hepatitis with rare epithelial intranuclear viral inclusions and multifocal arteriolar endothelial necrosis.

Contributor’s Comment: The lesions in this case are consistent with acute infection with canine herpesvirus-1 (CaHV-1). CaHV-1 is an Alphaherpesvirus which infects both domestic and wild canids and was first described as a cause of neonatal puppy mortality in the 1960s.2 It has a worldwide distribution and is antigenically similar to other Alphaherpesviruses of veterinary significance including feline herpesvirus-1, phocid herpesvirus-1 and equine herpesvirus-1 and 4.2,4

CaHV-1 is inactivated in temperatures over 40oC (104oF) and is readily broken down in the environment. Neonatal puppies aged less than 3 weeks of age become infected through direct contact and inhalation or ingestion of infected oronasal or genital secretions during passage through the birth canal, postnatal grooming by the dam or through contact with other shedding hosts including littermates.2,3,8 Following exposure, it is thought that CaHV-1 infects epithelial cells of the oropharynx and lymphocytes in the tonsils. Leukocyte trafficking in lymphocytes spreads the virus systemically, where it targets endothelial cells indiscriminately and epithelial cells of several organ systems including the kidney, spleen, lung and liver.8 Gross lesions in neonates are considered diagnostic and include miliary necrosis and petechial hemorrhages in multiple organs, particularly the kidneys.1,8 This is further confirmed by demonstration of intranuclear viral inclusion bodies, though other relevant diagnostic tests include virus isolation, immunofluorescence, and polymerase chain reaction.1 There may be pleural or peritoneal effusions, splenomegaly, lymphadenomegaly, and wet lungs with froth in the airways.7 This puppy also had a severe necrotizing bronchopneumonia with intranuclear inclusion bodies in the bronchiolar epithelial cells.

Ocular lesions may not always be obvious if the affected puppy’s eyelids are not yet open (after 10-14 days) and include panuveitis, retinitis and optic neuritis. Puppies that survive infection may have blindness, cataracts, optic nerve atrophy, and retinal degeneration or dysplasia.3 Meningoencephalitis may also be seen, with lesions including multifocal glial nodules and cerebellar cortical necrosis without significant inflammation.5

An incubation period of 3-10 days is followed by 1-3 days of nonspecific clinical signs including vomiting, inappetence and abdominal pain.2,7 The mortality rate can be up to 100% in some litters, with neonatal susceptibility thought to be due to a combination of immune naivety and a lower body temperature which improves the ability of CaHV-1 to enter cells, replicate and spread.2,8 Infected puppies may shed virus within respiratory and ocular secretions, saliva, urine and on mucosal surfaces, and thus serve as a source of virus for other littermates. Puppies that are infected after 3 weeks of age or those that have been exposed to maternally derived antibody are generally resistant to disease.3

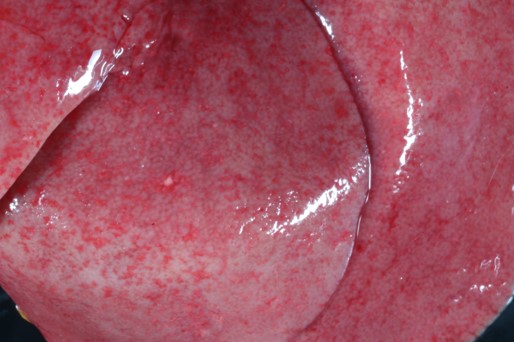

Infection of adult dogs and older puppies is associated with mild upper respiratory tract disease; CaHV-1 is yet to be shown to be a primary pathogen in canine infectious tracheobronchitis.1,7 Severe fibrinonecrotic or hemorrhagic bronchopneumonia leading to respiratory distress and death has been occasionally reported in adult dogs.6 Infection of a naïve dam during pregnancy can result in placental necrosis with mid-gestational abortion and stillbirths or weak puppies that die soon thereafter. Development of maternal antibody prevents disease in subsequent litters. Adult animals may also show lymphoid hyperplasia and hyperemia of the genital mucous membranes.2

CaHV-1 can establish latency within canids, existing within the trigeminal ganglia, lumbosacral ganglia, tonsils and parotid salivary glands. Recrudescence of infection can occur at times of physiological stress or treatment with immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids. These animals may serve as a source of infection within breeding colonies,2,3 and can shed virus from mucosal surfaces including those not involved in producing clinical disease.3. Serological studies may be of use in determining prevalence in kennels and at-risk breeding stock.1

Contributing Institution:

Massey University

School of Veterinary Science

Private Bag 11 222

Palmerston North 4442

New Zealand

JPC Morphologic Diagnosis: 1. Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing and random, moderate, with rare hepatocellular intranuclear viral inclusions.

2. Kidney: Nephritis, necrotizing, tubular and glomerular, multifocal, moderate.

JPC Comment: This second case is a double feature, with the contributor kindly sharing features of CaHV-1 in two separate tissues with us. Microscopic features of the virus were classic for alphaherpesviruses, with Dr. Pesavento remarking that changing the signalment of the animal to another (e.g. horse, cow) would still bring conference participants to consider their respective alphaherpesvirus (EHV-1, BHV1) accordingly. Canine adenovirus and sepsis are other important rule outs for this case. Adenovirus would also have intranuclear inclusions and centrilobular hepatic necrosis (due to ischemia and endotheliotropism) while CaHV-1 is more hepatotropic – animal age is therefore helpful in weighting these differentials. Bacterial sepsis should reflect a greater number of neutrophils which can be confirmed via a simple touch impression on the necropsy floor. Dr. Pesavento emphasized this point in her preconference lecture to participants and urged anatomic pathologists to develop basic familiarity with cytology and incorporate it to drive case management decisions during case prosection.

This case has overlap with Case 4 of this conference and both are best reviewed together. Here, intranuclear inclusions were sparse (especially in the kidney) though the constellation of microscopic features were nonetheless suggestive of CaHV-1. The gross image of the kidney reinforces this differential – we debated whether the subcapsular hemorrhage correlated with the expansion of the renal interstitium microscopically, though distinguishing between simple congestion versus hemorrhage was characteristically difficult. Dr. Pesavento highlighted several subtle slide features that pointed to this animal being very young, including fetal glomeruli with cuboidal epithelium, thinned renal cortex (decreased corticomedullary ratio) and decreased space between glomeruli, and smaller overall size of hepatocytes. From low magnification, the increased basophilia (colloquially, ‘blueness’) reflects these developing cells and the active transcription of nucleic acids therein.

References:

- Decaro N, Carmichael LE, Buonavoglia C. Viral reproductive pathogens of dogs and cats. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2012;42:583-598.

- Decaro N, Martella V, Buonavoglia C. Canine adenoviruses and herpesvirus. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2008;38:799-814.

- Evermann JF, Ledbetter EC, Maes RK. Canine reproductive, respiratory and ocular diseases due to canine herpesvirus. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2011;41:1097-1120.

- Gaskell R, Willoughby K. Herpesviruses of carnivores. Vet Micro. 1999;69:73-88.

- Jager MC, Sloma EA, Shelton M, Miller AD. Naturally acquired canine herpesvirus-associated meningoencephalitis. Vet Path. 2017;54(5):820-827.

- Kumar S, Driskell EA, Cooley AJ, et al. Fatal canid herpesvirus 1 respiratory infections in 4 clinically healthy adult dogs. Vet Path. 2015;52(4):681-687.

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals Volume 3. 6th ed. Missouri, USA: Elsevier; 2016:358-464.

- Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic basis of veterinary disease. 6th ed. Missouri, USA: Elsevier, 2017:132-241.