Signalment:

Gross Description:

Several organs, including the lungs, were formalin-fixed and sent for histopathology.

Histopathologic Description:

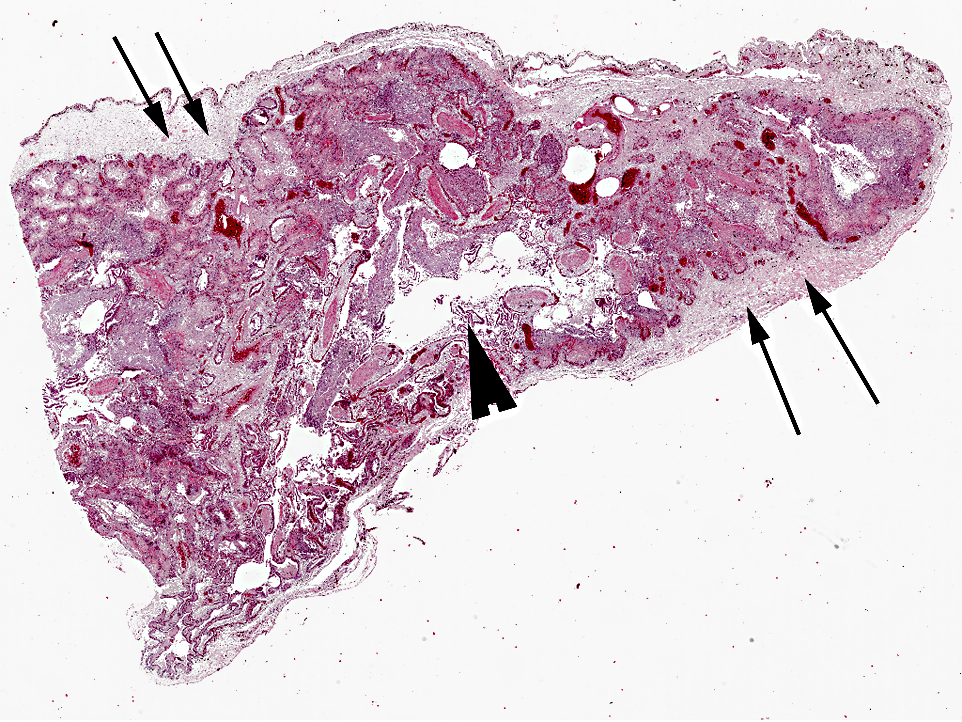

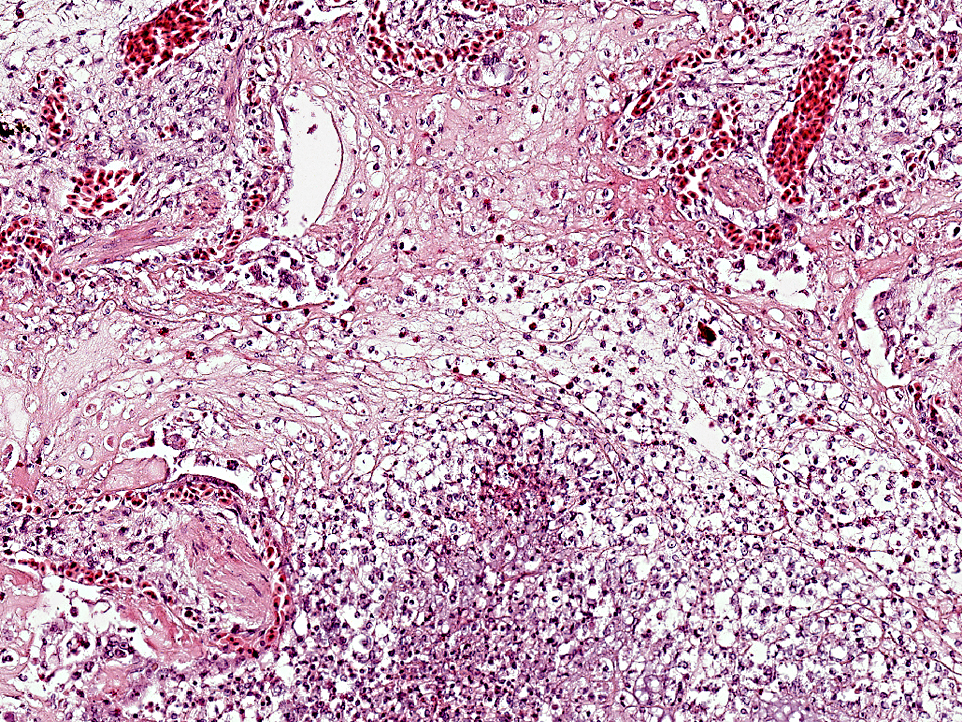

The pulmonary interstitium is moderately to severely and diffusely expanded by hyperaemia and edema, numerous heterophils and lesser numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Pleura is severely, diffusely edematous and contains a small number of heterophils.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Etiology: Chelonid herpesvirus (most likely type 3)

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Herpesviruses have also been associated with oral, respiratory, cutaneous, and genital lesions in Atlantic loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caret)(13) and skin diseases in sea turtles, such as gray patch disease and fibropapillomatosis in green turtles (Chelonia mydas).(1,7,12)

The exact route of transmission of herpesvirus in wild chelonids is still unknown. In captive animals, a major means of transmission is the exchange of pet tortoises between private collections.(8) It is very likely that direct contact between affected animals and unaffected tortoises represents the primary route of transmission. The finding of viral particles in testicular epithelium of Greek and Hermanns tortoises suggests the possibility of vertical transmission.(8) Herpesviruses identified in various species of turtles and tortoises have been preliminarily named chelonid herpesviruses (ChHVs), but represent an up-to-now unassigned species in the herpesvirus family. Classification of ChHVs is mainly based on putative differences in the host spectrum and 4 variants have been recognized. ChHV-1 was first described in association with gray patch disease in captive green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the West Indies.(12) This disease is characterized by patchy gray areas of hyperkeratotic and necrotic papules that occur over the head, neck, and flippers. ChHV-2 was seen in two Pacific pond turtles (Clemmys marmorata) with fatal hepatic necrosis. A similar disease has been seen in painted turtles (Chrysemys pict a) and in map turtles (Graptemys pseudogeographica) in association with herpesvirus-like particles.

These viruses have been preliminarily named ChHV-3.6 ChHV-4 was seen in tissues of Argentinian tortoises (Geochelone chilensis) with necrotizing stomatitis or mouth rot. Interestingly, red-footed tortoises (Geochelone carbon aria) kept together with the diseased Argentinian tortoises remained clinically healthy.(4) Epizootics of chronic seromucous rhinitis (running nose syndrome) were described in large populations of captive T. graeca. This outbreak was part of a series of epidemic ChHV infections that have occurred in Europe during the last decade. In most cases, outbreaks follow shared housing of different tortoise species after addition of new animals. In all of these cases, presumed carrier species, especially T. graeca, remained healthy, whereas other, presumably less resistant species, became sick or died.Â

Clinical signs in tortoises include nasal serous to mucopurulent discharge, open mouth breathing, wheezing, dyspnea, lethargy, anorexia, weight loss and ataxia. Radiographs, magnetic resonance, CT scans, bronchoscopy, and cytology have been used for clinical diagnosis.(8)

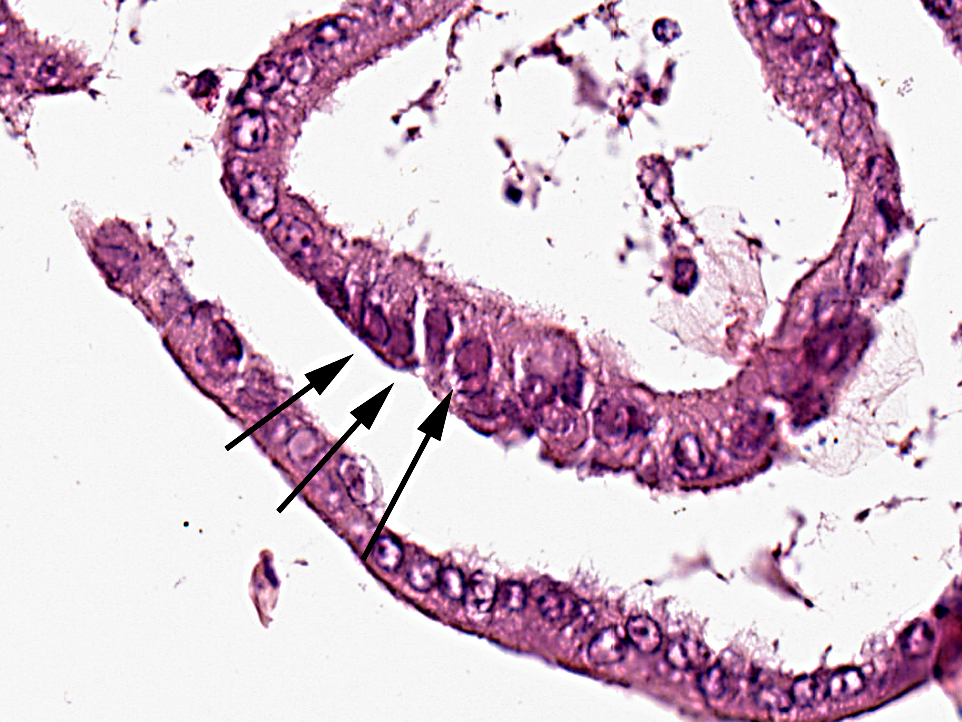

Pathological findings in most chelonids with respiratory disease include necrotizing caseous stomatitis that extends in the oral cavity and nares and necrotizing glossitis with presence of diphtheritic plaques. Lower airways can be involved resulting in necrotizing pneumonia and emphysema. Enteritis and hepatomegaly have been also reported.(8) In tortoises, eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions are commonly seen in epithelial cells of affected tissues stained with haematoxylin and eosin and are associated with syncytial cells.(8) Secondary bacterial complications are associated with development of multiple bacterial granulomas. Intranuclear inclusions have also been reported in lung and trachea of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) with respiratory disease(5) and in cutaneous fibropapillomas.(7) Using TEM, virions can be detected in the nucleus and cytoplasm of infected cells of the tongue, trachea, bronchi and alveoli, endothelial cells of glomerular capillaries and within neurons and glial cells of the medulla oblongata and diencephalon.(8)

Tests that have been developed to diagnose chelonid herpesvirus include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of herpesvirus antibodies in plasma samples of Mediterranean tortoises.(9) Indirect and direct immunoperoxidase assay have been used either for assessing the presence of anti-herpesvirus antibody in tortoise plasma or for detecting herpesvirus antigen in tissues.(10)

ChHV DNA has been demonstrated in a broad range of formalin fixed and paraffin embedded tissues in tortoises suffering from stomatitisrhinitis complex by in situ hybridization and PCR. The ISH signal colocalizes to the same areas and cell types that contain intranuclear inclusions in haematoxylin and eosin stained tissue sections from tortoises of different geographic provenances. Nuclear hybridization signals have been detected in epithelial cells of the lingual mucosa and glands, in tracheal epithelium, pneumocytes, hepatocytes, the renal tubular epithelium, cerebral glial cells and neurons, intramural intestinal ganglia and in endothelial cells of many organs.(14)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Ranavirus is in the family Iridovirus, with gross lesions including hepatic necrosis, ulcerative tracheitis, pneumonia, and ulcerative pharyngitis and esophagitis. Histopathologic findings include basophilic intracytoplasmic viral inclusions in hepatocytes and epithelial cell, and fibrinoid vasculitis in multiple organs. Reptiles are thought to aquire ranavirus from amphibians.(3)

Fibropapillomatosis is found in all species of sea turtles except for the leatherback, and is caused by a herpesvirus. Fibropapilloma-associated turtle herpesvirus causes a debilitating disease characterized by large numbers fibropapillomas which result in decreased mobility and occasional blindness when located near the eyes. These are often accompanied by anemia and immunosuppression. Histology of the masses is that of a typical fibropapilloma, and intranuclear viral inclusions are rarely seen. Fibropapillomas can also be seen on the viscera, with the kidney and lung being primary target tissues(16).Â

References:

2. Herbst LH, Jacobson ER, Klein PA, et al. Comparative pathology and pathogenesis of spontaneous and experimentally induced fibropapillomas of green turtles (Chelonia mydas). Vet Pathol. 1999;36:551-564.

3. Jacobson ER. Viruses and viral diseases of reptiles. In: Jacobson ER, ed. Infectious Diseases and Pathology of Reptiles. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007:396-405.

4. Jacobson ER, Clubb S, Gaskin JM, et al. Herpesvirus-like infection in Argentine tortoises. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;187:12271229.

5. Jacobson ER, Gaskin JM, Roelke M, et al. Conjunctivitis, tracheitis, and pneumonia associated with herpesvirus infection in green sea turtles. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:1020-1031.

6. Jacobson ER, Gaskin JM, Wahlquist H. Herpesvirus-like infection in map turtles.J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982;181:13221324.

7. Jacobson ER, Mansell JL, Sundberg JP, et al. Cutaneous fibropapillomas of green turtles (Chelonia mydas). J Comp Pathol. 1989;101:3952.

8. Origgi FC, Jacobson ER. Diseases of the respiratory tract of chelonians. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2000;3:37-549.

9. Origgi FC, Klein PA, Mathes K, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting herpesvirus exposure in Mediterranean tortoises (spur-thighed tortoise [Testudo graeca] and Hermann's tortoise [Testudo hermanni]). J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3156-3163.Â

10. Origgi FC, Klein PA, Tucker SJ, et al. Application of immunoperoxidase-based techniques to detect herpesvirus infection in tortoises. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2003;15:133-140.

11. Peitan-Brewer KCB, Drew ML, Ramsay E, et al. Herpesvirus Particles Associated With Oral and Respiratory Lesions in a California Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizi). J Wildlife Dis. 1996;32:521-526.Â

12. Rebell G, Rywlin A, Haines H. A herpesvirus-type agent associated with skin lesions of green sea turtles in aquaculture. Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:12211224.

13. Stacy BA, Wellehan JF, Foley AM, et al. Two herpesviruses associated with disease in wild Atlantic loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Vet Microbiol. 2008;126:63-73.

14. Teifke JP, Lo HR CV, Marschang RE, et al. Detection of Chelonid Herpesvirus DNA by Nonradioactive In Situ Hybridization in Tissues from Tortoises Suffering from StomatitisRhinitis Complex in Europe and North America. Vet Pathol. 2000;37:377385.

15. Rivera S, et al. Systemic adenovirus infection in Sulawesi tortoises (Indotestudo forsteni) caused by a novel siadenovirus. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21(4):415-26.

16. Wyneken J, Mader DR, Weber III ES, et al. Medical care of seaturtles. In: Mader DR, ed. Reptile Medicine and Surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:986-91.