CASE 1: S1808480 (4135076-00)

Signalment: A 12-week-old, female raccoon (Procyon lotor)

History: Raccoon presented with a history of progressive illness and diarrhea.

Gross Pathology:

The carcass was in fair nutritional condition, with a small amount of fat reserves, but still well fleshed. Bilaterally, the lungs were diffusely, moderately wet and had increased firmness, with multifocal to coalescing, whitish/cream-colored discoloration. The lumen of the distal portion of the trachea and main bronchi contained soft to friable, yellowish material. The perianal region and fur were matted with yellowish fecal material. Minimal contents were found in the small intestine, and the large intestine contained small amounts of yellowish-greenish pasty contents.

Laboratory results:

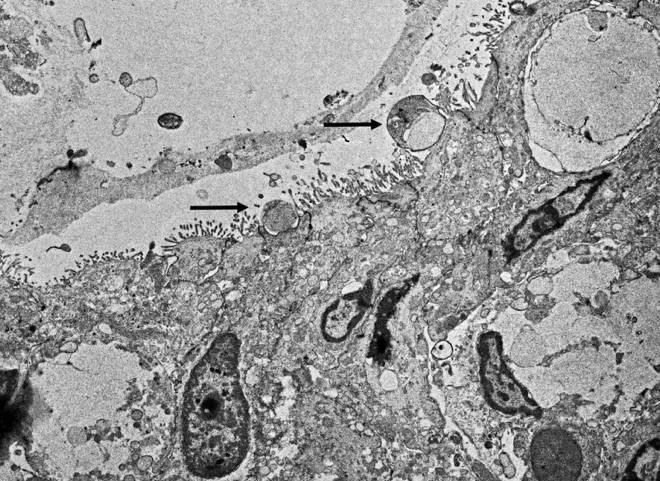

Cryptosporidium sp. was detected by PCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene on mucosal scrapes of the small intestine of this raccoon. The sequenced amplicon clustered with the Cryptosporidium skunk genotype. We also performed additional fecal analysis using special stains (modified acid fast) which showed rare numbers of Cryptosporidium spp. ELISA was performed on small intestine contents being also positive for Cryptosporidium spp. Transmission electron microscopy also demonstrated small rounded protozoa compatible with Cryptosporidium spp. No parasite eggs were detected in feces via fecal flotation.

CDV immunohistochemistry in lung and intestinal tissue was positive. Canine parvovirus immunohistochemistry was negative on intestine tissue.

Additional tests performed on this case include a negative rabies test, and moderate numbers of Escherichia coli isolated from lung tissue.

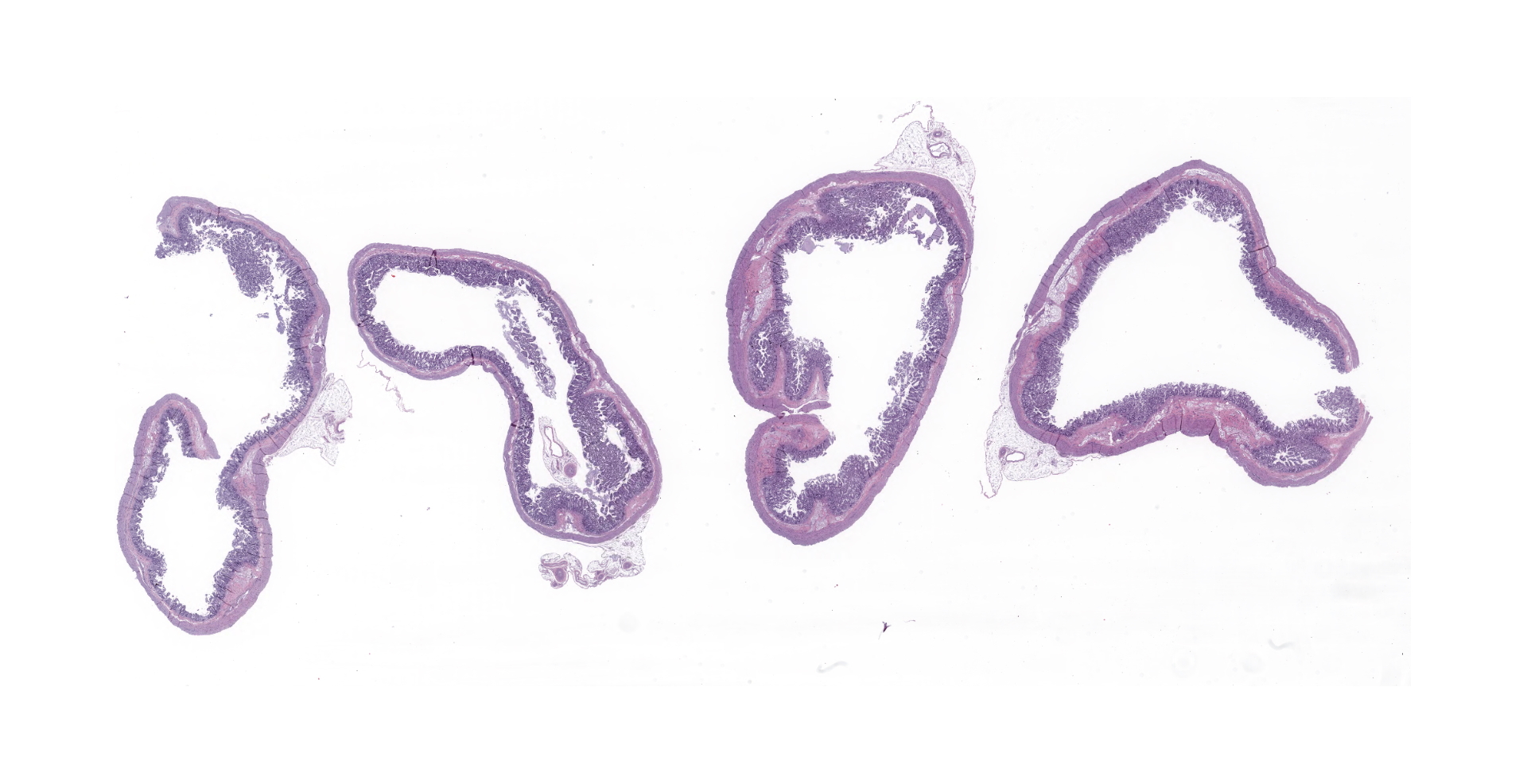

Microscopic description:

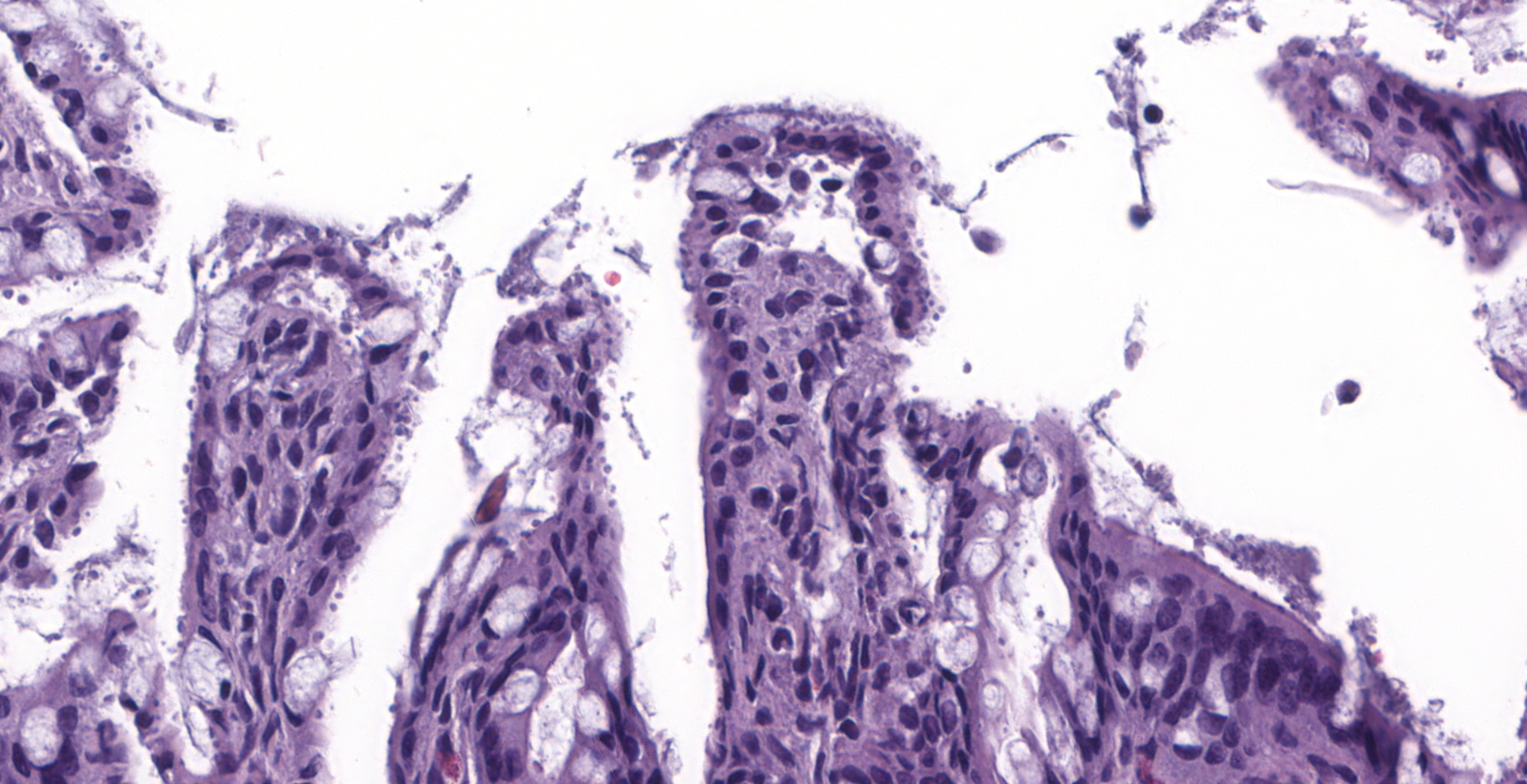

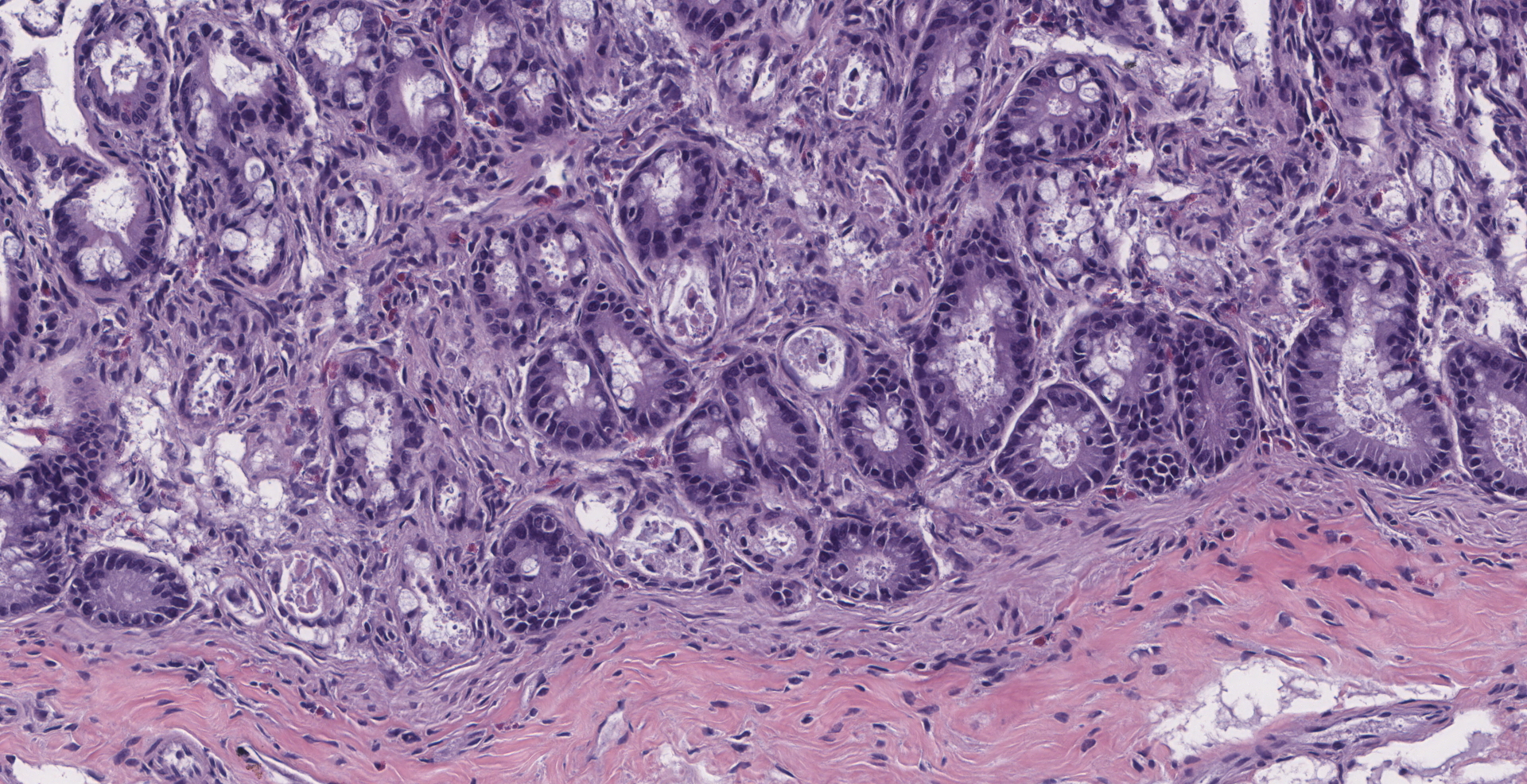

There is diffuse atrophy of the intestinal mucosa (villus atrophy) and multifocal infiltration of eosinophils in the lamina propria. Lining the apical portions of the intestinal epithelium are multiple, 5-10 um round, heterogeneously basophilic structures (morphology compatible with Cryptosporidium sp.). There is multifocal necrosis of crypt epithelium, while in other areas crypts appear multifocally dilated and lined by attenuated epithelium. These dilated crypts often contain sloughed epithelial cells, cell debris, and a small number of neutrophils in crypt lumina.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Small intestine: Enteritis, necrotizing, with villus atrophy, crypt necrosis and intralesional cryptosporidia, raccoon (Procyon lotor)

Other morphological diagnoses (not present in slide): Bronchointerstitial pneumonia, diffuse, marked, with intracytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusion bodies (compatible with infection by canine distemper virus); splenic lymphoid depletion, mild to moderate.

Contributor's comment:

Cryptosporidiosis is a protozoal disease of public health importance, caused by Cryptosporidium spp., a group of apicomplexan parasites that cause intestinal disease and are found in several vertebrate species including mammals, reptiles, birds and humans. Due to habitat encroachment from urbanization of forested land, wildlife species are coming into contact with human pathogens and becoming accidental carriers. Because of this, there is an interest in determining the carrier status of synantropic wildlife (species co-habiting in urbanized land), such as raccoons for human pathogens.

Raccoons may play a possible role in contaminating the environment, including urban areas and ecosystems, with pathogens of zoonotic relevance such as Cryptosporidium spp. and microsporidia (Enterocytozoon sp. and Encephalitozoon sp.), being either carried by these animals or acquired by interaction with other wildlife.

Cryptosporidium skunk genotype

Until recently, it was thought that Cryptosporidium spp. showed a strong host-adaptation and thus wildlife infections did not appear to pose a risk to human health. This thought becomes evident in the taxonomy of Cryptosporidium species, where many are still named after their host and are still referred to as 'host adapted'. Nevertheless, recent evidence suggests that some wildlife adapted genotypes are capable of inducing intestinal disease in humans,17 which is a concern especially in areas where numerous host species commingle and share resources which turn into common infection sources (e.g. contaminated water).

Multi-locus genetic characterization indicate that host adaptation is a general phenomenon of Cryptosporidium as specific genotypes tend to be detected in similar groups of animals.24 These studies have also detected an extensive genetic diversity within Cryptosporidium which may suggest that host-parasite co-evolution may contribute to the genetic heterogeneity observed.24 Currently, there are 20 valid species recognized for Cryptosporidium. The majority of human infections are caused by Cryptosporidium hominis or Cryptosporidium parvum, but Cryptosporidium meleagridis, Cryptosporidium felis, Cryptosporidium canis, Cryptosporidium suis, Cryptosporidium muris, Cryptosporidium andersoni, Cryptosporidium hominis monkey genotype, cervine genotype, and the chipmunk genotype I have also been detected.

Multiple studies in the early 2000s found that in Europe the C. parvum bovine genotype was the main cause of human infections instead of C. parvum human genotype.2,10 The human genotype is still the main cause of infections in humans elsewhere in the world, but this finding justifies the investigation of other genotypes as causative agents of human diarrheal disease. Raccoons are infected by the skunk genotype, which was thought to only be found in wild or zoo animals.21,24 The skunk, rabbit and horse genotypes were found in three separate cases of human diarrhea in the UK.17 Other known hosts for the Cryptosporidium skunk genotype include the Eastern gray, American red and fox squirrels, river otters, and striped skunks in the USA.22,25

Distemper and raccoons

Distemper is caused by the canine distemper virus (CDV) of the genus Morbillivirus, family Paramyxoviridae, a virus spread by body excretions and secretions (urine), an important pathogen with a fatality rate only overtaken by rabies in domestic dogs.23 CDV is capable of inducing virulent disease in a range of mammals, particularly in juveniles. If animals overcome the infection, they can develop lifelong immunity or die within a short time post-infection (20-120 days).1 Natural and vaccine-induced infections have been reported in all families of terrestrial carnivores and also in free-ranging felids where the virus has recently caused large-scale epidemics.3,19

Clinical signs include diarrhea, dyspnea, neurological signs and profound immunosuppression.4 There are regular epidemics in free-ranging raccoons in the U.S., indicating that the infection is endemic in some North American raccoon populations, playing a role in the distemper epidemiology in domestic dogs and non-domestic zoo populations.

As mammals, all procyonids are susceptible to natural CDV infections, resulting in multiple records of natural CDV infections in raccoons and vaccine-induced infections in kinkajous (Potos flavus).6,11,12,13,18,20 Clinical presentation in procyonids is presumed to be similar to that of domestic dogs, including cystitis with pyuria,16 as well as diarrhea, dyspnea, and profound immunosuppression.4 Raccoons can develop neurological signs and become icteric.12 It is possible that the profound immunosuppression caused by CDV makes raccoons (especially young individuals) vulnerable to be colonized by moderate to large numbers of cryptosporidia, and exacerbates gastrointestinal signs.

Changes to the crypts similar to those observed in this case are highly suggestive of canine parvovirus. However, testing for this virus was negative. It is possible that these changes were produced by Cryptosporidium infection as previously reported.8 It is also possible that the crypt changes were associated with concomitant distemper virus infection.7

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory, UC Davis, San Bernardino branch.

https://cahfs.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/locations/san-bernardino-lab

JPC diagnosis:

1. Intestine: Villar blunting, diffuse, severe, with mild eosinophilic enteritis and numerous epithelial-associated apicomplexan schizonts and gamonts, raccoon, procyonid.

2. Intestine: Enteritis, necrotizing, multifocal, mild, with multifocal crypt abscesses.

JPC comment:

During the conference, there was debate about what cellular components are required to designate something a "crypt abscess." The literature varies between human pathology and veterinary pathology, and the standard terminology does not transfer between disciplines seamlessly. In human pathology, a neutrophilic component is required to be present to form a crypt abscess, while in veterinary pathology it may be composed of sloughed and necrotic cells without neutrophils. While the debate focused on terminology, the most important aspect of this topic is proper identification of neutrophils when present in order to more correctly identify the pathologic process.

Cryptosporidiosis has been documented in mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, and other species. In coccidia, the whole life cycle is completed in a single host. While the lifecycle and life stages help classify coccidia from other apicomplexans, there are ultrastructural features that provide more specific classification. Visible structures in apicomplexans include a conoid, rhoptries, and micronemes.5

In 1993, in Milwaukee, Michigan, spring snowmelt and rainwater raised the water level of the Menomonee and Kinnickinnic rivers as they fed the Milwaukee, ultimately dumping into Lake Michigan. The public drinking water of Milwaukee came from Lake Michigan and was processed according to federal water treatment guidelines and testing. Unfortunately, the largest concern of the time was bacterial pathogens, and large amounts of chlorine was assumed to be sufficient treatment. Unfortunately, the increased water flow had carried Cryptosporidium oocysts into Lake Michigan, through the treatment facilities, and to the faucets of residents. Ultimately, new tests using ELISA and fluorescent antibodies were used to find oocysts in the drinking water. Following the resolution of this outbreak, it was estimated that approximately 400,000 people had fallen ill, with about 4000 hospitalized, and more than 100 people had died, making this the largest waterborne outbreak of disease in the United States at the time.14

In a study of Cryptosporidium outbreaks in human populations from 2009-2017, there were 444 outbreaks recorded, across 40 states and Puerto Rico. The two most implicated risks included exposure to treated recreational water (pools, water playgrounds, and similar) in 35% of cases, and contact with cattle in nearly 15% of cases.9

While apicomplexans cause significant disease in terrestrial animals most often, there are marine animals that exist with a more symbiotic relationship with these parasites. Research on the shipworm, a marine mollusk that burrows in and eats submerged wood, gastrointestinal tract revealed no microbial flora. Intracellular bacteria in the gills of the clam produce cellulolytic enzymes necessary for digestion of wood, but also plays a role in maintaining a sterile gut environment. A compound called tartrolon E (trtE) was isolated and found to have broad anti-apicomplexan activity in vitro, including in vivo efficacy against Cryptosporidium parvum in neonatal mice. This may represent the basis for a new therapy for this common disease across the world.15

References:

1. Almberg ES, Mech LD, Smith DW, Sheldon JW, Crabtree RL: A serological survey of infectious disease in Yellowstone National Park's canid community. PLoS One 2009:4(9):e7042.

2. Alves M, Matos O, Antunes F: Multilocus PCR-RFLP analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from HIV-infected patients from Portugal. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2001:95(6):627-632.

3. Appel MJ, Yates RA, Foley GL, Bernstein JJ, Santinelli S, Spelman LH, et al.: Canine distemper epizootic in lions, tigers, and leopards in North America. J Vet Diagn Invest 1994:6(3):277-288.

4. Beineke A, Baumgartner W, Wohlsein P: Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update. One Health 2015:1:49-59.

- Cheville NF. Ultrastructural Pathology: The Comparative Cellular Basis of Disease, 2nd Ed. Wiley-Blackwell:Ames, IA. 2009:549-558.

6. Cranfield MR, Barker IK, Mehren KG, Rapley WA: Canine distemper wild raccoons at the Metropolitan Toronto Zoo. Canadian Veterinary Journal 1984:25:63-66.

7. Denholm KM, Haitjema H, Gwynne BJ, Morgan UM, Irwin PJ: Concurrent Cryptosporidium and parvovirus infections in a puppy. Aust Vet J 2001:79(2):98-101.

8. Gelberg HB: Alimentary System and the Peritoneum, Omentum, Mesentery, and Peritoneal Cavity. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathology Basis of Veterinary Disease. St Louis, Missouri, USA: Elsevier, Inc.; 2017: 324-411.

- Gharpure R, Perez A, Miller AD, Wikswo ME, Silver R, Hlavsa MC. Cryptosporidiosis Outbreaks - United States, 2009-2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;68(25).

10. Guyot K, Follet-Dumoulin A, Lelievre E, Sarfati C, Rabodonirina M, Nevez G, et al.: Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates obtained from humans in France. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2001:39:3472?3480.

11. Kazacos KR, Thacker HL, Shivaprasad HL, Burger PP: Vaccination-induced distemper in kinkajous. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1981:179(11):1166-1169.

12. Kilham L, Habermann RT, Herman CM: Jaundice and bilirubinemia as manifestations of canine distemper in raccoons and ferrets. Am J Vet Res 1956:17(62):144-148.

13. Mitchell MA, Hungeford LL, Nixon C, Esker T, Sullivan J, Koerkenmeier R, et al.: Serologic survey for selected infectious disease agents in raccoons from Illinois. J Wildl Dis 1999:35(2):347-355.

- Morris, RD. The Blue Death: Disease, Disaster, and the Water We Drink. Oneworld Publications: Oxford, England. 2007.

- O'Connor RM, Nepveux FJ, Abenoja J, et al. A symbiotic bacterium of shipworms produces a compound with broad spectrum anti-apicomplexan activity. PLoS Pathogens. 2020; 16(5):e1008600.

16. Pare JA, Barker IK, Crawshaw GJ, McEwen SA, Carman PS, Johnson RP: Humoral response and protection from experimental challenge following vaccination of raccoon pups with a modified-live canine distemper virus vaccine. J Wildl Dis 1999:35(3):430-439.

17. Robinson G, Elwin K, Chalmers RM: Unusual Cryptosporidium genotypes in human cases of diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis 2008:14(11):1800-1802.

18. Robinson VB, Newberne JW, Brooks DM: Distemper in the American raccoon (Procyon lotor). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1957:131(6):276-278.

19. Roelke-Parker ME, Munson L, Packer C, Kock R, Cleaveland S, Carpenter M, et al.: A canine distemper virus epidemic in Serengeti lions (Panthera leo). Nature 1996:379(6564):441-445.

20. Roscoe DE, Holste WC, Sorhage FE, Campbell C, Niezgoda M, Buchannan R, et al.: Efficacy of an oral vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein recombinant vaccine in controlling epidemic raccoon rabies in New Jersey. J Wildl Dis 1998:34(4):752-763.

21. Ryan U, Xiao L, Read C, Zhou L, Lal AA, Pavlasek I: Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from the Czech Republic. Appl Environ Microbiol 2003:69(7):4302-4307.

22. Stenger BLS, Clark ME, Kvac M, Khan E, Giddings CW, Prediger J, et al.: North American tree squirrels and ground squirrels with overlapping ranges host different Cryptosporidium species and genotypes. Infect Genet Evol 2015:36:287-293.

23. Swango LJ: Canine viral diseases. In: Ettinger SJ, and E. C. Feldman (eds.). ed. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine: Diseases of the Dog and Cat.: W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. ; 1995: 398-409.

24. Xiao L, Sulaiman IM, Ryan UM, Zhou L, Atwill ER, Tischler ML, et al.: Host adaptation and host-parasite co-evolution in Cryptosporidium: implications for taxonomy and public health. Int J Parasitol 2002:32(14):1773-1785.

25. Ziegler PE, Wade SE, Schaaf SL, Stern DA, Nadareski CA, Mohammed HO: Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in wildlife populations within a watershed landscape in southeastern New York State. Vet Parasitol 2007:147(1-2):176-184.