Signalment:

Gross Description:

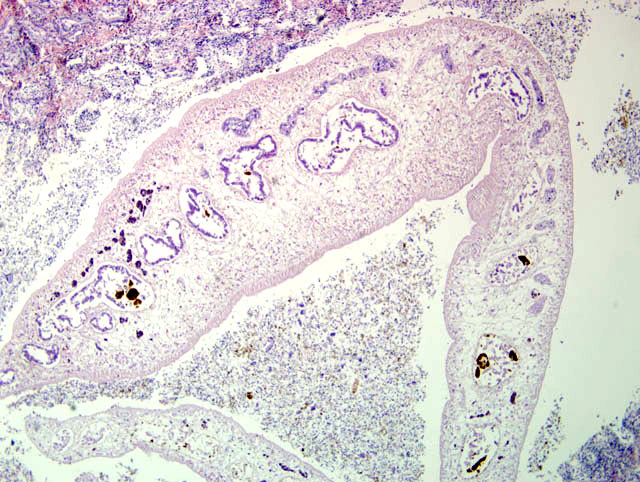

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Fascioliasis is common in cattle and sheep. The life cycle of Fasciola hepatica includes a Lymnead snail as an intermediate host. The snail is found in damp environments, such as marshy ground, ponds, and along the banks of slow moving streams. The miracidia of Fasciola hepatica, which are ingested along with the feces of the final host, infect the snail by burrowing through its body wall. Once within the snail, the larvae pass through a number of developmental stages including a sporocyst, three generations of rediae, and finally a cecarial stage which leaves the snail and encysts on vegetation to become a metacercaria. The infective metacercariae are ingested by the final host and excyst within the duodenum and migrate to the liver. Adult flukes reside in the bile ducts.(3)

In comparison to cattle and sheep, equids appear to mount an, as yet poorly understood, early immunological challenge to infection, which leads to the destruction, immobilization or developmental retardation of the larval flukes, the result being that only a few trematodes reach maturity in the bile ducts of equids.(2)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Given the limited clinical information and history provided to participants, i.e. species of animal affected, most favored D. dendriticum as the causative agent. In addition to infecting horses, this trematode also infects ruminants, pigs, dogs and cats. Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica primarily affect sheep and cattle. Wild cervids are the natural host for F. magna, though it can infect cattle and sheep. Other trematodes infecting domestic animals include: Eurytrema pancreaticum and E. coelomaticum in ruminants; Opisthorchis viverrini in cats and dogs; and Pseudamphistimum truncatum, Metorchis spp., Parametorchis complexus, Concinnum procyonis, and Platynosum fastosum in cats and dogs.(1)

Two possible sequelae to hepatic trematodiasis are black disease in sheep and bacillary hemoglobinuria in sheep and cattle. Black disease occurs when anaerobic, necrotic foci in the liver resulting from F. hepatica migration allow ingested Clostridium novyi spores in the liver to germinate. Once active, C. novyi elaborates a necrotizing beta toxin and hemolytic phospholipase C, and together, these toxins produce large areas of coagulative necrosis in the liver resulting in severe edema, congestion, hemorrhage and death, often with no premonitory signs. The pathogenesis of bacillary hemoglobinuria, caused by Clostridium haemolyticum, is similar to black disease with respect to the fluke involved, germination of spores, and toxin production. The toxins of C. haemolyticum produce intravascular hemolysis with associated anemia and hemoglobinuria.(1)

References:

2. Eckert J. Helminthosen der Equiden. In: Rommel M, Eckert J, Kutzer E, K+�-�rting W, Schnieder T, eds. Veterin+�-�rmedizinische Parasitologie. 5th ed. Parey; 2000:353-354.

3. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Infectious diseases of the liver. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed., vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2007:354-356, 359-362.

4. Wintzer HJ, Kraft W. Parasit+�-�re Krankheiten des Pferdes. In: Wintzer HJ, ed. Krankheiten des Pferdes. 3th ed. Parey; 1999:229.

5. Uslu U, Guclu F. Prevalence of endoparasites in horses and donkeys in turkey. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2007;51: 237-240.