Signalment:

Gross Description:

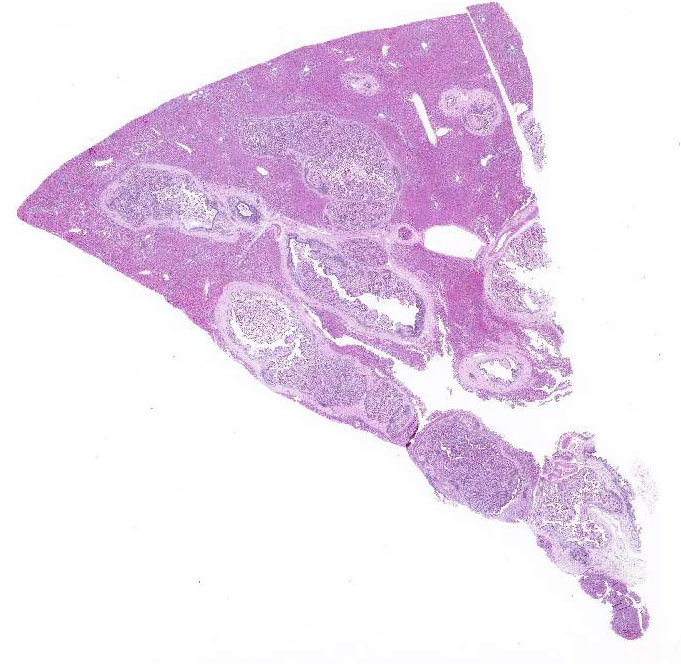

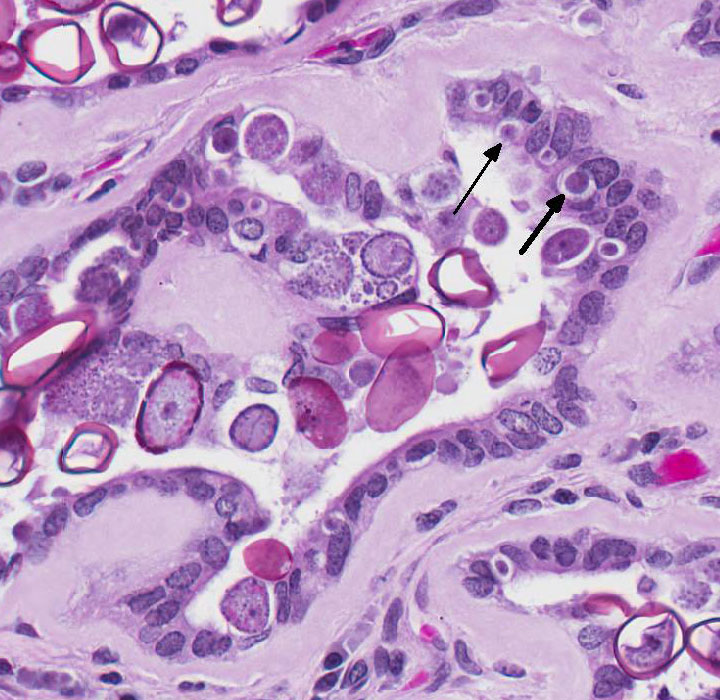

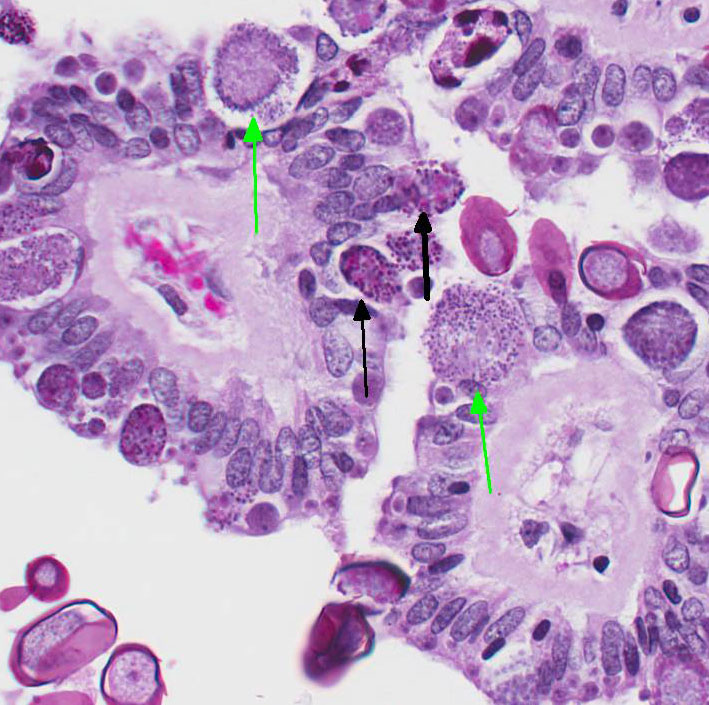

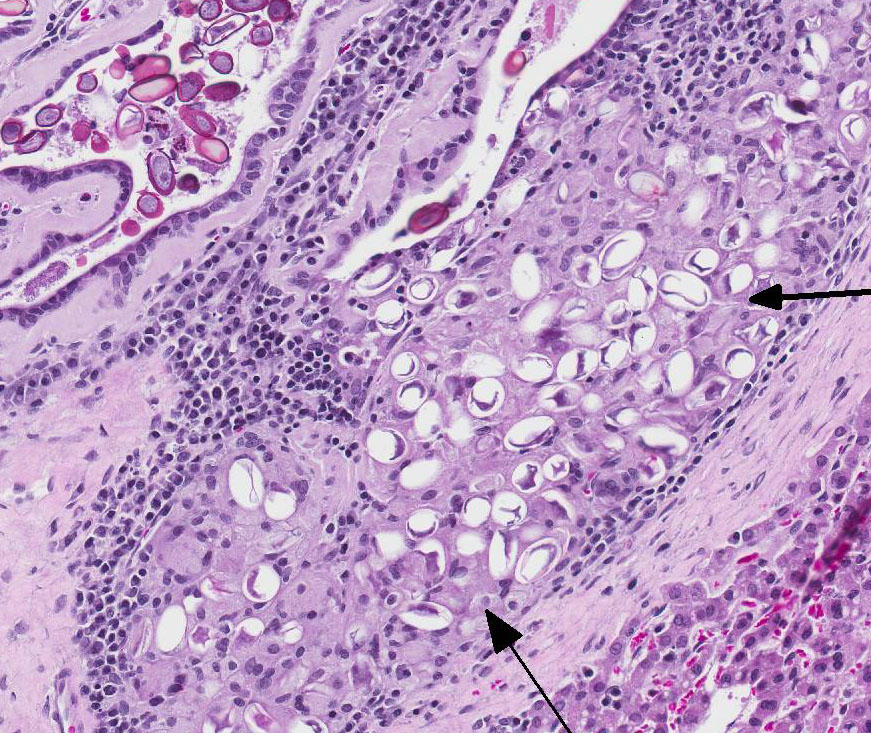

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

|

Nonpathogenic |

Slightly Pathogenic |

Pathogenic |

Highly Pathogenic |

|

E. coecicola (appendix, sacculus rotundus, Peyers patches) |

E. perforans (entire small intestine) |

E. media (duodenum to jejunum) |

E. intestinalis (lower jejunum and ileum) |

|

|

E. exingua (emall intestine |

E. magna (jejunum and ileum) |

E. flavescens (small intestine and cecum) |

|

|

E. vejdovskyi (ileum) |

E. piriformis (colon) |

|

|

|

|

E. irresidua (jejunum and ileum |

|

After ingestion of sporulated oocysts, sporozoites penetrate the duodenal mucosa and eventually spread to the liver by lymphatic and hematogenous routes.4 Upon reaching the liver, the sporozoites invade the biliary epithelium and enter the typical coccidian life cycle of schizogony, then gametogony with production of oocysts that are released into the bile ducts and passed into the intestine.4 The prepatent period is approximately 15-18 days.4

The severity of disease appears to be related to the initial dose level of the oocyst inoculum.3 Antemortem diagnosis is typically made by clinical signs and demonstration of oocysts in the feces. Post-mortem findings of the proliferative biliary lesions and histological identification of the organisms are pathognomonic for the disease.4 Control of hepatic coccidiosis can be achieved with improvement of hygienic conditions, particularly removal of fecal material containing oocysts before they finish sporulation.3 As it is probably impossible to remove all oocysts, control is augmented by prophylaxis with different anticoccidian drugs.1,3 It should be noted that some are better than others and drugs that are effective in controlling chicken coccidiosis are not always efficacious in rabbits.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Eimeria sp. typically cause subclinical disease but can cause serious illness in young and immunosuppressed lagomorphs. Over 11 species of coccidian parasites have been described in rabbits and E. stiedae is the only coccidian parasite found in the liver and biliary epithelium .3,4 As mentioned by the contributor, the rabbit is infected by ingestion of sporulated oocysts in the feces with sporozoites invading the duodenal mucosa. Sporozoites have been documented in the regional lymph nodes within 12 hours, in bone marrow within 24 hours, and in the liver within 48 hours via hematogenous spread by infecting mononuclear cells.4 Rabbits with hepatic coccidiosis are often co-infected with intestinal Eimeria sp. Intestinal Eimeria sp. target specific segments of the intestinal tract in rabbits and are divided into four groups based on pathogenicity in the following table:

Table adapted from Pakandl M3 and Percy DH and Barthold SW4 The marked proliferation of the biliary epithelium, seen in this case, is secondary to destruction and regeneration of the bile duct epithelium with extensive hyperplasia of the ductular epithelium. In addition, biliary outflow may be obstructed by numerous oocysts within the lumen of the bile duct resulting in cholestasis and further distention of the bile duct.4

Conference participants discussed whether this case represents cholangiohepatitis with inflammation extending into the hepatic parenchyma or simply cholangitis with secondary mild centrilobular atrophy of hepatocytes and replacement by bridging fibrous connective tissue. Conference participants overwhelmingly agreed with the contributor that while the markedly dilated bile ducts compress the adjacent hepatic parenchyma, there is no disruption of the hepatic limiting plate; thus favoring the morphologic diagnosis of lympho-plasmacytic cholangitis.

References: