Signalment:

Two-year-old, hermaphrodite, veiled chameleon, (

Chamaeleo calyptratus).Initially the

chameleon exhibited open mouth breathing and declining appetite, eventually

requiring forced feeding. The patient returned to the clinic 4 weeks later with

severe dehydration and obvious weight loss. The chameleon was euthanized at

that time.

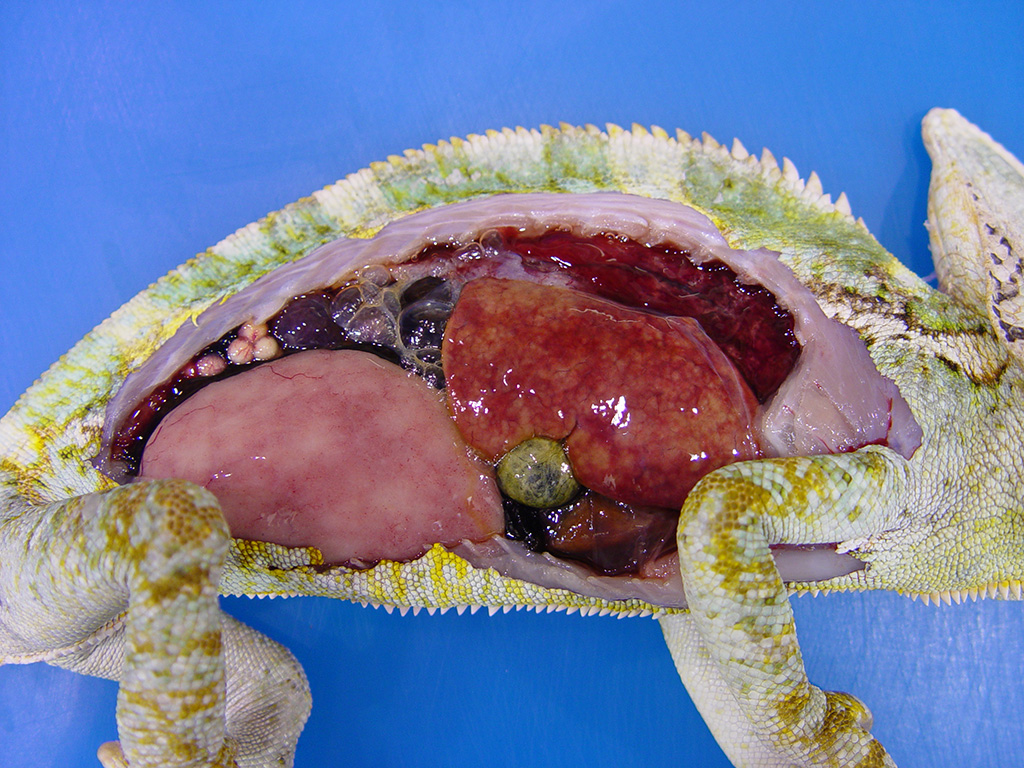

Gross Description:

The

chameleon was in good nutritional condition with normal muscle mass and

moderate coelomic adipose stores. A small amount of clear red-tinged fluid was

present in the coelom. Diffuse red discoloration was evident in the expanded

lungs and the liver was mottled tan and red with slight rounding of the

margins. Ovotestes were present bilaterally. Mucoid content was evident in the

lumen of the stomach and the colon; the intestinal content was otherwise scant.

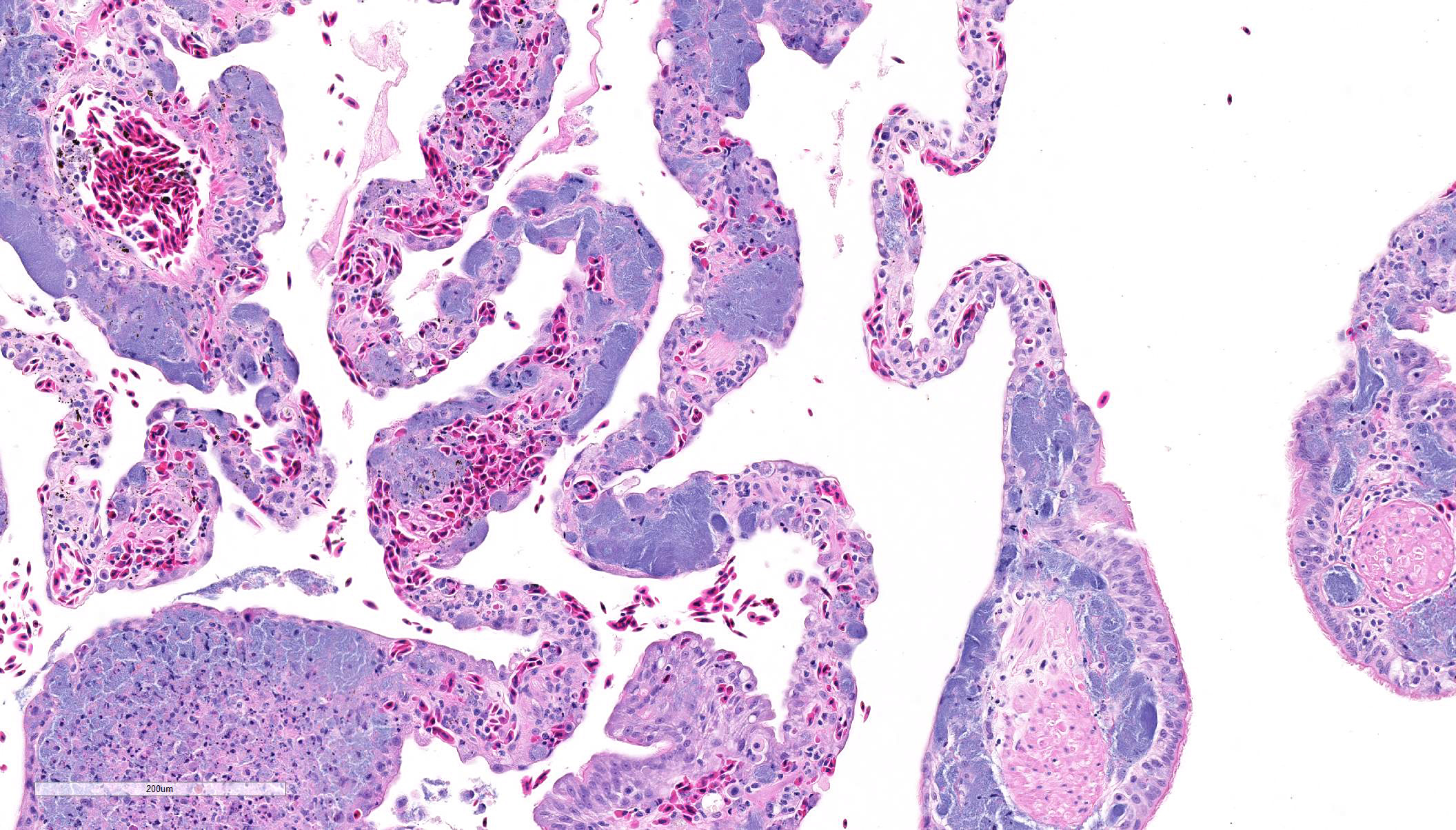

Histopathologic Description:

Lung:

The faveolar septa are expanded with moderate to marked congestion of the

vasculature and myriad slender bacilli are present within the lumina of blood

vessels; bacteria are both free within the lumina and present within the

cytoplasm of macrophages. Hemorrhage, intravascular fibrin thrombi and necrotic

cellular debris often accompany the bacterial colonies and scattered small

aggregates of epithelioid macro-phages are present multifocally in the septa.

In areas, there is necrosis of the faveolar epithelium and erythrocytes,

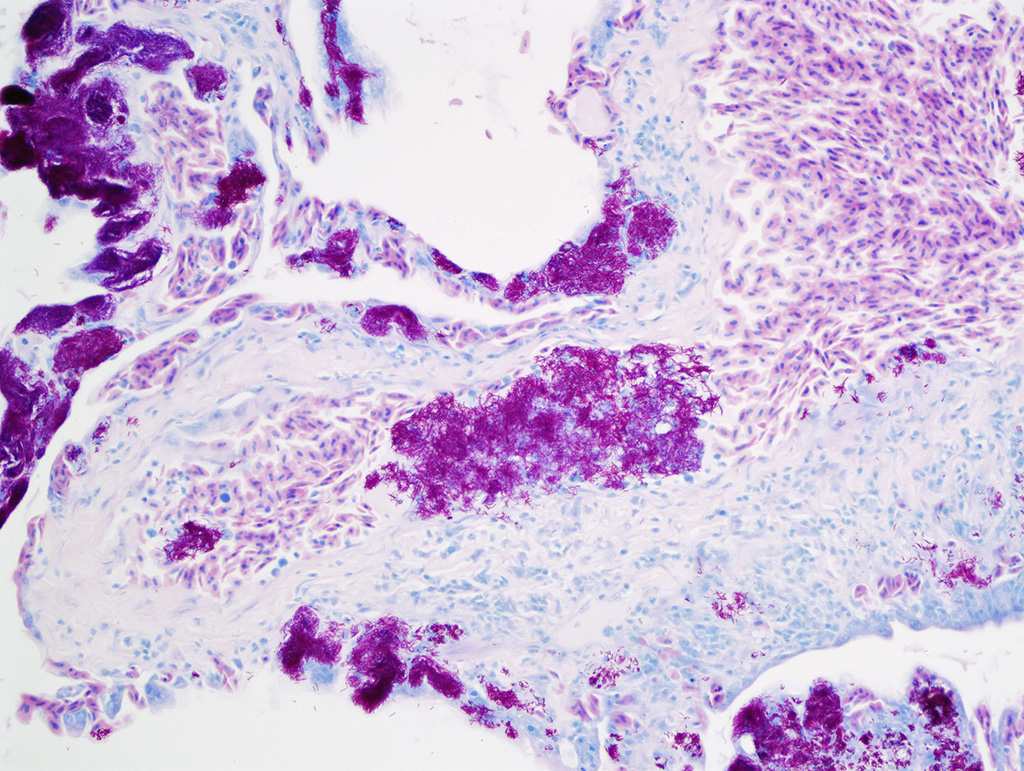

proteinaceous fluid and cellular debris are noted with the faveolar spaces. The bacteria are acid-fast

with the Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Similar

intravascular bacteria and occasional small aggregates of macrophages

containing bacteria are present in most organs (liver, pancreas, kidney, brain,

spleen, skeletal muscle, adrenal glands, small intestine and ovotestes).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Necrotizing and histiocytic

interstitial pneumonia, diffuse, subacute, with myriad

intravascular/intrahistiocytic acid-fast bacilli and intravascular fibrin

thrombi

Lab Results:

Sections of lung were

submitted for bacterial culture. Primary culture on a sheep

blood agar plate after 48 hour aerobic incubation at 37

oC

resulted in heavy growth of tiny smooth cream-colored colonies. Grams

stain revealed pleomorphic gram-positive bacilli. The

bacteria were acid-fast with the Ziehl-Neelsen stain. The

isolate was sent to the National Reference Centre for Mycobacteriology (Public

Health Agency of Canada). Based on

16s and

hsp65 gene

sequencing, the isolate had 100% sequence identity to

Mycobacterium

chelonae chemovar

niacinogenes.

Condition:

Pneumonia/Mycobacterium chelonae

Contributor Comment:

Mycobacteria

are ubiquitous in nature and can be isolated from the soil, dust, water and

bioaerosols.

1 Reptiles are generally thought to acquire

mycobacterial infections via ingestion or through defects / penetrating injury

in the skin.

11 In this chameleon, there was a localized area of

intestinal ulceration and granulomatous enteritis, suggesting that infection

may have been acquired through the intestinal tract. In

reptiles, like most species, mycobacterial infections tend to be chronic with

rare acute infections reported.

5 The typical gross lesions are

grey-white nodules in multiple organs. Microscopically, early lesions are

composed of organized collections of foamy macrophages that with time may

become chronic granulomas composed of a mixture of epithelioid macrophages,

lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells often surrounding a

central region of necrosis and occasionally with a surrounding wall of fibrous

connective tissue.

11 In this case, there were a few small early

granulomas in multiple organs including the brain, lung, liver, kidneys and

intestine. More striking, however, was the presence of myriad intravascular

bacteria in multiple organs and frequent intravascular fibrin thrombi. These

changes are compatible with acute to subacute infection with acute bacteremia

and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Mycobacteria are

broadly divided into two groups:

Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and

non-tuberculous myco-bacteria.

2 While only non-tuberculous

mycobacteria have been reported to cause infections in reptiles, several

different species have been associated with these infections. These include

M.

confluentis,

M. chelonae, M. haemophilum, M. hiberniae, M. neoarum, M.

confluentis, M. nonchromogenicum, M. marinum, and M. thamnopheos.

2,5,11

The most common causes of mycobacteriosis in reptiles are reported to be

M.

marinum,

M. chelonae and

M. thamnopheos.

5 The

isolate in this case was confirmed to be

M. chelonae chemovar

niacinogenes.

Non-tuberculous

mycobacteria are classified into four Runyon groups according to growth rate

and pigmentation.

5 Runyon group I mycobacteria are slow growing and

form pigment in the light following growth in the dark. Runyon group II

organisms are also slow growing bacteria; these bacteria form pigment in the

dark following growth in the light. Runyon group III bacteria are slow growing

and do not form pigment in the dark or light. Fast growing non-pigmented

mycobacteria are placed in Runyon group IV. These mycobacteria form mature

colonies on solid agar within 7 days, while bacteria in Runyon groups I to III

take longer periods of time for cultivation.

2 Most mycobacteria which

infect reptiles fall into Runyon groups I and IV.

5 Mycobacterium

chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria belonging to Runyon group IV.

4

Rapidly growing mycobacteria are relatively resistant to standard disinfectants

and antibiotic treatment and are increasingly recognized as opportunistic

pathogens in humans.

1,2

In

reptiles

, M. chelonei has been reported in association with

osteoarthritis

in a Kemps Ridley sea turtle,

4 with stomatitis and subcutaneous

granulomas in a boa constrictor,

6 and with disseminated infection in

a loggerhead sea turtle

8 and a veiled chameleon.

9 There

is a single report of this bacterium causing acute fatal sepsis and

disseminated intravascular coagulation in an eastern spiny softshell turtle

8

with lesions very similar to those described in this case. Because of poor

response to treatment and the zoonotic potential, euthanasia is often

recommended for reptiles with myco-bacterial infections.

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, histiocytic and necrotizing, multifocal to

coalescing, moderate, with numerous intrahistiocytic and intravascular bacilli, veiled

chameleon,

Chamaeleo calyptratus.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides an outstanding review of non-tuberculous

Mycobacteria in reptiles.

Mycobacteria spp. are a large genus

comprised of over 100 species of obligate pathogenic, potentially pathogenic,

and environmental saprophytic bacteria.

6 They are all

morphologically similar and are composed of aerobic, gram-positive, acid-fast,

non-spore forming bacilli.

6 Conference participants were impressed

by the large numbers of intrahistiocytic and intravascular thin filamentous

bacilli that stain slightly basophilic on hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue

section. These bacilli are intensely acid-fast positive with Fite-Faraco and

Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stains, run by the Joint Pathology Center prior to the

conference.

Mycobacterium chelonae infection,

confirmed by the contributor as the cause of rapid disseminated disease in this

animal, is an opportunistic and potentially zoonotic pathogen that is

characterized by rapid growth and high resistance to antibiotics.

1,2

As mentioned by the contributor, spontaneous non-tuberculous

Mycobacteria

sp., including

M. avium,

M. chelonae,

M. szulagai,

M.

fortuitum,

M. marinum,

M. hemophilum,

M. kansasii, and

M. ulcerans have been reported to be the classic etiologic agents that

cause histiocytic granulomas snakes, turtles, lizards, and crocodiles and

should top the list of differential diagnoses for lesions similar to this case.

2,5,10,11

The obligate intracellular bacteria,

Chlamydophila pneumoniae, can also

occasionally infect reptilian species and induce histiocytic granulomas and

should be considered as a differential diagnosis. Additionally, relatively

recently described Chlamydia-like bacteria

Parachlamydia acanthamoebae

and

Simikania negevensis, have been sporadically reported to form

histiocytic granulomas in reptiles as well.

11

While

histiocytic granulomas in reptiles are often induced by intracellular bacteria,

such as in this case, heterophilic granulomas in reptiles are caused by

extracellular pathogens, including most bacterial and fungal etiologies. Tissue

injury can also induce heterophilic granulomas in reptiles.

5

Heterophilic granulomas are characterized by accumulation and degranulation of

heterophils leading to a central area of necrosis, stimulating a strong

macrophage foreign body-like response. Caseocalcareous nodules, lymphoid

infiltration, and peripheral fibrosis, typical of mammalian granulomas, have

not been observed in reptilian heterophilic granulomas.

5 Both

histiocytic granulomas and heterophilic granulomas can progress to chronic

granulomas, characterized by a fibrous connective tissue capsule, lymphocytes

and plasma cell infiltration, and a central area of necrosis with a prominent

lamellated appearance.

5

References:

1. De Groote MA, Huitt G. Infections

due to rapidly growing

Mycobacteria.

Clin Infect Dis. 2006;

42:175663.

2. Ebani,

VV, Fratini F, Bertelloni F, et al. Isolation and identification of

Mycobacteria

from captive reptiles.

Res Vet Sci. 2012; 93:11361138.

3. Fremont-Rahl

JJ, Ek C, et al.

Mycobacterium liflandii outbreak in a research colony

of Xenopus (Silurana) tropicalis frogs.

Vet Pathol. 2011; 48(8):856-867.

4. Greer

LL, Strandberg JD, Whitaker BR.

Mycobacterium chelonae osteoarthritis in

a Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle (

Lepidochelys kempii).

J Wildl Dis. 2003;

39(3):736-741.

5. Jacobson,

ER. Bacterial diseases of reptiles. In: Jacobson ER, ed.

Infectious Diseases

and Pathology of Reptiles: Color Atlas and Text. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC

Press; 2007: 461526.

6. Mauldin E,

Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed.

Jubb, Kennedy, and

Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia,

PA:Elsevier; 2016:639-641.

7. Mitchell MA. Mycobacterial infections in reptiles.

Vet

Clin Exot Anim. 2012; 15(1):10111.

8. Murray

M, Waliszewski NT, Garner MM, et al. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular

coagulation in an eastern spiny softshell turtle (

Apalone spinifera

spinifera) with acute mycobacteriosis.

J Zoo Wildl Med. 2009;

40(3):572-575.

9. Nardini

G, Florio D, DiGirolamo N, et al. Disseminated mycobacteriosis in a stranded

Loggerhead Sea Turtle (

Caretta caretta).

J Zoo Wildl Med. 2014;

45(2): 357360.

10. Reavill

DR, Schmidt RE. Mycobacterial lesions in fish, amphibians, reptiles, rodents,

lagomorphs, and ferrets with reference to animal models.

Vet Clin Exot Anim.

2012; 15(1): 2540.

11. Soldati

G, Lu ZH, Vaughan L, et al. Detection of

Mycobacteria and

Chlamydiae

in granulomatous inflammation of reptiles: A retrospective study.

Vet Pathol.

2004; 41(4):388397.