CASE II: G7740 (JPC 3105937).

Signalment: 2-month-old intact female red-handed tamarin (Saguinus midas), nonhuman primate.

History: The animal belonged to a group of tamarins (Saguinus midas) on exhibit at a German Zoo. The group was established with one breeding couple. Reproduction has been successful and the female has given birth to 20 children. Out of these, two were born dead and six infants died within the first three month after birth. The group lived in an indoor-outdoor enclosure. The tamarin was one of two offspring of the year 2007. The other offspring was found dead 12 days earlier with similar symptoms. The parents remained clinically healthy. This monkey was euthanized due to a poor prognosis.

Gross Pathology: The tamarin was in a poor body condition. There was little content in stomach and intestinal tract. The great parenchymas were free of macroscopically conspicuous alterations. The brain was hyperemic with scattered foci of malacia.

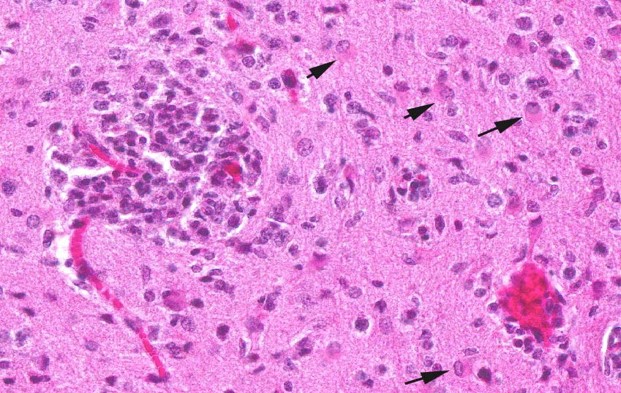

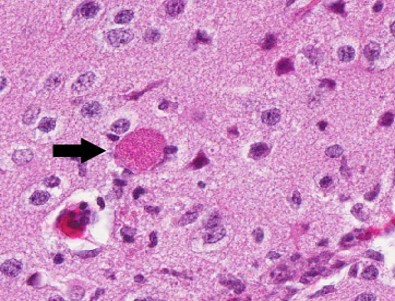

Contributor?s Histopathologic Description: Histopathologic examination revealed granulomas in brain, heart and liver. The granulomas occurred in all parts of the brain and were frequently found adjacent to small blood vessels. They consisted of macrophages, lymphocytes and few granulocytes. Protozoan organisms were found within the granulomas. They occurred free or within pseudocysts. Individual ovoid organisms measured 2.5 x 1.5 µm, pseudocysts were about 60 ? 120 mm in diameter and contained numerous individual organisms. The lesions were followed by non-suppurative meningitis. Organisms were demonstrable within the meninges. The morphology of these organisms was consistent with microsporidia. Organisms of this type were also detected in other histologically unchanged organs. Pseudocysts and spores were gram positive and Giemsa positive single organisms in the pseudocysts reacted acid fast.

Immunohistochemistry: Encephalitozoon cuniculi: positive, provided by Prof. Pospischil, University Zürich, Switzerland

Immunohistochemistry for Toxoplasma gondii: negative

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis: CNS: encephalitis, granulomatous, subacute, multifocal, severe, with myriad intralesional and free laying protozoa, etiology consistent with Encephalitozoon cuniculi, tamarin (Saguinus midas), nonhuman primate.

Contributor?s Comment: Encephalitozoonosis is caused by Encephalitozoon cuniculi, an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite of the family Pleistophoridae and the phylum Microspora. E. cuniculi is a small oval parasite that measures 2.5 x 1.5

µm. The organism is characterized by a coiled polar filament in the mature spore stage. Ruptured mature spores release the organisms into the surrounding environment and infect other cells. The parasite is able to infect a variety of cell types but there is a predilection for macrophages, cells of the central nervous system and renal tubular epithelium. Spores are passed out with the urine.

Infections may be acquired horizontally or vertically. Infection of mammals most often occurs by ingestion or inhalation of contaminated urine or feces shed by the infected host. Transplacental transmission has also been described.

Microsporidia of the genus Encephalitozoon are well recognized pathogens in a wide range of hosts. E. cuniculi and other members of the microsporidial HIV-infected immunocompromised humans. To date, three different Encephalitozoon species are identified. The different strains have different host preferences and were designated according to their main host as ?rabbit strain?, ?mouse strain? and ?dog strain?. Furthermore, the three strains differ in their geographic distribution. The rabbit strain has a worldwide distribution, the mouse strain occurs in Europe only, and the dog strain has been identified in America and South Africa only.

Natural E. cuniculi infection may occur in nonhuman primates. Most reported cases involved different New World monkey species, mainly infant squirrel monkeys.1,2,8 Furthermore, E. cuniculi was detected in emperor tamarins3 and cotton top tamarins.5 Clinically, signs of infected monkeys are usually absent or the animal develops nonspecific clinical disorders prior to death. The occurrence of latent infections is possible. Infections may be associated with stillbirths, abortions and perinatal deaths. Encephalitozoon infection in a colony can be diagnosed clinically by serologic investigation.6

Diagnosis can be made by finding the parasites and the typical associated lesions during histopathologic examination of the tissue or by demonstrating the agent in the urine.

E. cuniculi must be differentiated from Toxoplasma gondii in histological sections. Staining properties of the organism and the nature of the inflammatory response can help to differentiate it from other infections.E. cuniculi stains poorly with hematoxylin and eosin, but stains well with Giemsa, Gram, periodic acid- Schiff (PAS) and Ziehl-Nielson. Encephalitozoon is gram-positive and variably acid fast, which is consistent with microsporidia and distinct from protozoa such as Toxoplasma or Neospora. Toxoplasma does not stain with a gram-stain. Furthermore, Toxoplasma cysts are smaller than Encephalitozoon pseudocysts, and individual Toxoplasma organisms are larger and crescent shaped, while Encephalitozoon is smaller and ovoid.2 Electron microscopy can reveal the presence of the typical parasitophorous vacuoles as well as the distinctive polar filaments. The polar filament may be coiled up to six times around the inner wall of the spore or may be extruded. Immunological or molecular techniques are best suited to distinguish between different protozoan species and strains.

parasites have been regaining interest as opportunistic pathogens for individuals with a compromised immune system.

E. cuniculi is known for its widespread occurrence in rabbits and is an important opportunistic pathogen in

JPC Diagnosis: Brain: Meningoencephalitis, granulomatous, multifocal, marked, with gliosis and numerous microsporidian pseudocysts.

Conference Comment: Encephalitozoon exhibits selective parasitism of vascular endothelium, especially in the brain and kidney, as well as renal tubular epithelium. Spores, which are the infective stage, usually obtain entry through the digestive tract, and the sporoplasm, which contains the genetic material, is either released and engulfed by macrophages or injected into endothelial cells through the extruded polar filament. Asexual replication occurs to form numerous proliferative meronts, which differentiate into sporoblasts and then sporonts. A dense spore wall is produced over the plasma membrane, which thickens and allows spore organelles to form. Spores are then packaged within a parasitophorous vacuole, which enlarges and causes host cell rupture. There is release of spores into the extracellular spaces, which then can infect adjacent cells, or enter the vascular system or the renal tubular lumen to be passed in the urine.4,7

Typical gross lesions in nonhuman primates include granulomatous meningoencephalitis and vasculitis, nonsuppurative interstitial nephritis and pneumonia, and granulomatous placentitis. A ?classic? gross lesion in the rabbit is multifocal irregularly depressed pits in the kidneys with indistinct linear pale gray-white streaks on cut surface. In severe cases, hydrocephalus, thrombosis of meningeal blood vessels, and focal encephalomalacia can occur.2,4,7 In the dwarf rabbit, which is especially susceptible, E. cuniculi has been associated with phacoclastic uveitis and cataract formation, in addition to meningoencephalomyelitis and radiculoneuritis.4

In addition to the electron microscopy findings of a parasitophorous vacuole and coiled polar filament mentioned by the contributor, a corrugated proteinaceous electron dense exospore, a chitinous radiolucent endospore, an anchoring disc at the anterior pole, and an electron lucent posterior vacuole are present.7

Contributor: German Primate Center Department of Infectious Pathology Kellnerweg 4

37077 Göttingen Germany http://dpz.eu

References:

1. Asakura T, Nakamura S, Ohta M, et al. Genetically unique microsporidian Encephalitozoon cuniculi strain type III isolated from squirrel monkeys. Parasitol. Intern. 2006;55:159 -162.

2. Baskin G. Enzephalitozoon cuniculi infection, squirrel monkey. In: TC Jones TC, Mohr U, Hunt RD, eds. Nonhuman Primates II. 1993;193-196.

3. Guscetti F, Mathis A, Hatt J-M, et al. Overt fatal and chronic subclinical Encephalitozoon cuniculi microsporidiosis in a colony of captive emperor tamarins (Saguinus imperator). J. Med. Primatol. 2003;32:111-119.

4. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007;290-4.

5. Reetz J, Wiedemann M, Aue A, et al. Disseminated lethal Encephalitozon cuniculi (genotype III) infections in cotton-top tamarins (Oedipomidas oedipus) ? a case report. Parasitol. Intern. 2004;53:29?34.

6. Shadduck JA, Baskin G. Serologic evidence of Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection in a colony of squirrel monkeys. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1989;39:328?330.

7. Wasson K, Peper RL. Mammalian microsporidiosis. Vet Pathol. 2000;37(2):113-28.

8. Zeman DH, Baskin G. Encephalitozoonosis in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). Vet Pathol. 1985;22:24?31.

9. Baskin G. Enzephalitozoon cuniculi infection, squirrel monkey. In: TC Jones TC, Mohr U, Hunt RD, eds. Nonhuman Primates II. 1993;193-196.

10. Guscetti F, Mathis A, Hatt J-M, et al. Overt fatal and chronic subclinical Encephalitozoon cuniculi microsporidiosis in a colony of captive emperor tamarins (Saguinus imperator). J. Med. Primatol. 2003;32:111-119.

11. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007;290-4.

12. Reetz J, Wiedemann M, Aue A, et al.

Disseminated lethal Encephalitozon cuniculi (genotype III) infections in

cotton-top tamarins (Oedipomidas oedipus) ? a case report. Parasitol.

Intern. 2004;53:29?34.

13. Shadduck JA, Baskin G. Serologic evidence of Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection

in a colony of squirrel monkeys. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1989;39:328?330.

14. Wasson K, Peper RL. Mammalian microsporidiosis. Vet Pathol. 2000;37(2):113-28.

15. Zeman DH, Baskin G. Encephalitozoonosis in

squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). Vet Pathol. 1985;22:24?31.