Signalment:

Gross Description:

Icterus, hemoabdomen, perirenal hemorrhage, subendocardial hemorrhage

Liver-Ç-öpale yellow-brown, flaccid, 2.3 Kg (0.99% body weight)

Histopathologic Description:

Changes in the cerebrum (slide not submitted to WSC) included increased space around vessels and cortical neurons with Alzheimer type II astrocytes (hypertrophied and hypochromatic nuclei). These changes were considered consistent with hepatic encephalopathy. In addition, many deep cortical neurons had ischemic change with a shrunken angular profile, intense cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and pyknosis.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

| Test | Result | Reference Range |

| Packed cell volume (PCV) | 58% | 35-50% |

| Segmented neutrophils | 0.4 x 103/μL | 6.0-12.0 x 103/μL |

| Total Protein | 7.6 g/dL | 5.7-8.1 g/dL |

| Lactate | 7.2 mmol/L | <2 mmol/L |

| Fibrinogen | 112 mg/dL | 115-289 mg/dL |

| Glucose | <20 mg/dL | 73-124 mg/dL |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | 3 mg/dL | 8-27 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 2.0 mg/dL | 0.6-1.8 mg/dL |

| TCO2 | 19 mmol/L | 23-31 mmol/L |

| Anion gap | 26.4 mmol/L | 12-20 mmol/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 3,563 IU/L | 206-810 IU/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 933 IU/L | 109-331 IU/L |

| γ-Glutamyl transferase (GGT) | 158 IU/L | 12-46 IU/L |

| Creatine kinase (CK) | 9811 IU/L | 88-453 IU/L |

| Bilirubin | 21.1 mg/dL | 0.10-2.60 mg/dL |

| Unconjugated | 15.3 mg/dL | |

| Conjugated | 5.8 mg/dL | |

| Blood ammonia | 254.4 μmol/L | 25.0-75.0 μmol/L |

Aerobic and anaerobic bacterial culture: no significant growth.

PCR for Theilers disease-associated flavivirus (TDAV), Cornell University Animal Health Diagnostic Center: nNegative.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Postmortem gross and histologic lesions were typical of Theilers disease, hence the PCR testing for Theilers disease-associated virus (TDAV). This horse was negative by PCR for TDAV, but the serum was positive for a previously unreported non-flavivirus that is under investigation (personal communication, Drs. Bud Tennant, Tom Divers and colleagues at Cornell University and Columbia University).

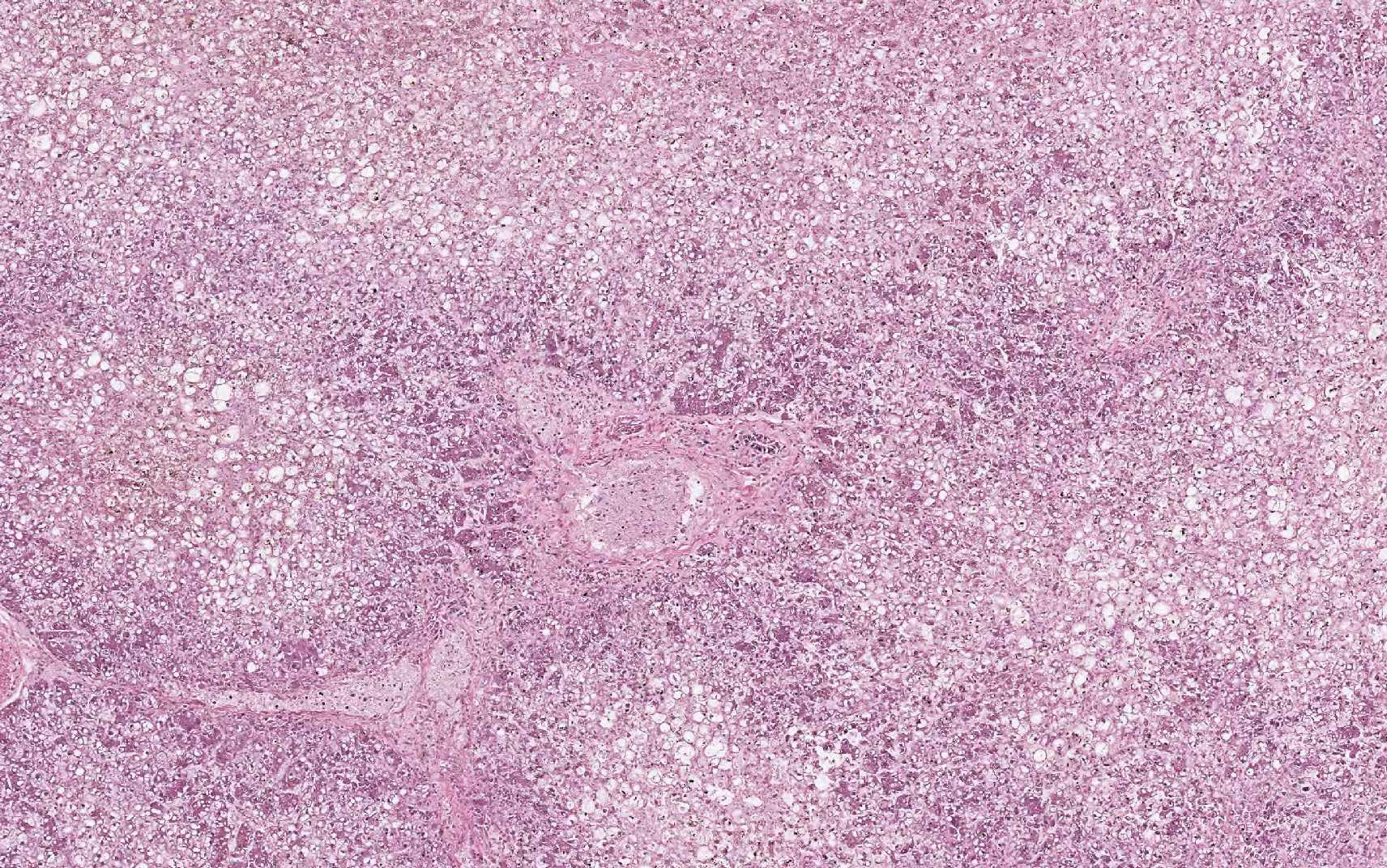

Equine serum hepatitis or Theilers disease was first described in 1919, when Arnold Theiler reported acute hepatic atrophy and hepatitis in South African horses vaccinated against African horse sickness with an equine antiserum-containing live virus vaccine.(6) Today, Theilers disease is usually recognized in horses 4-10 weeks after injection with a product that contains equine serum or plasma, though some affected horses have no history of injection with equine blood containing biologic products. Although the incubation period is long (42-90 days), clinical disease (subclinical cases are also recognized) is fulminating with acute hepatic failure and death within 24 hours in up to 90% of clinically ill horses. At autopsy, the carcass is icteric. The liver is generally close to normal size, but flaccid (dish-rag liver) due to massive necrosis with loss of so many hepatocytes. The histologic lesion is centrilobular to massive necrosis with mild, mainly lymphocytic, inflammation of portal tracts. Surviving periportal hepatocytes are swollen with vacuolated cytoplasm.

Theilers disease has long been suspected to be a viral hepatitis, but the first candidate virus, Theilers disease-associated virus (TDAV, a pegivirus in the Flaviviridae family), was only identified a few years ago in horses treated with equine antiserum to botulinum toxin.(1) Another pegivirus called equine pegivirus has been identified in horses, but has not been documented to cause hepatitis.(4) The recently discovered non-primate hepacivirus (NPHV, equine hepacivirus) is another member of the Flaviviridae family that is hepatotropic and can result in transient or chronic infection with elevated hepatic enzymes and hepatitis in horses.(3-5) Many horses (30-40%) have serum antibodies to NPHV; fewer horses have detectable viral RNA in the peripheral blood. The horse has been proposed as an animal model of viral hepatitis because NPHV is so closely related to the human hepatitis C virus.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

In this case, conference participants described diffuse loss of hepatic cord architecture with hepatocellular degeneration, necrosis and loss. There is stromal collapse and mild portal bridging fibrosis. The brown pigment present within Kupffer cells and hepatocytes was interpreted as hemosiderin. The section is moderately autolytic and there is abundant acid hematin present.

We thank the contributor for providing clinical pathology data with the submission, which greatly enhances the teaching and learning value of the case. Severe neutropenia is most commonly associated with endotoxemia, but the precise etiology is difficult to ascertain in this case. Elevated packed cell volume (PCV) is likely secondary to dehydration and the normal total protein is indicative of hypoproteinemia in a dehydrated animal. Low fibrinogen, blood urea nitrogen, elevated ammonia and low glucose are indicators of liver failure. The profoundly low glucose is not compatible with life and may indicate some degree of artifact. The decreased TCO2 and elevated anion gap are indicative of a metabolic acidosis and the unmeasured anions in this case include lactate and renal acids. Elevated AST is secondary to both myocyte and hepatocyte damage and elevated CK provides additional evidence of muscle damage. Elevated GGT and ALP are both indicators of cholestasis and the most common cause of elevated total bilirubin horses is anorexia. The hyper-bilirubinemia in this case is higher than can be attributed to anorexia alone and, therefore; the remarkable hepatic changes likely contribute to the elevation. Elevated bilirubin can also be seen in cases of endotoxemia due to impaired excretion of conjugated bilirubin into the biliary tract.

References:

1. Chandriani S, Skewes-Cox P, Zhong W, Ganem DE, et al. Identification of a previously undescribed divergent virus from the Flaviviridae family in an outbreak of equine serum hepatitis. 2013. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013; 110(15):E1407-E1415.

2. Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:312-313.

3. Pfaender S, Cavalleri JMV, Walter S, Doerrbecker J, et al. Clinical course of infection and viral tissue tropism of hepatitis C virus-like nonprimate hepaciviruses in horses. Hepatology. 2015; 61(5):447-459.

4. Ramsay JD, Evanoff R, Wilkinson TE, Divers TJ, et al. Experimental transmission of equine hepacivirus in horses as a model for hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2015; 61(5):1533-1546.

5. Scheel TKH, Kapoor A, Nishiuchi E, Brock KV, et al. Characterization of nonprimate hepacivirus and construction of a functional molecular clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015; 112:2192-2197.

6. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA. Liver and biliary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 2. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO; 2007:297-388.