CASE 3: 18/75 (4118754-00)

Signalment: 9 years, female, Flat Coated Retriever dog (Canis familiaris)

History:

A week prior to euthanasia, the dog had problems keeping up with the owner on a run. Five days later the dog got generalized tonic-clonic seizures and salivation, but it was intermittently contactable between the seizures, each lasting 10-20 minutes. The dog was restless and seemed confused post-ictally, appeared to be blind, and circled to the left. Further clinical examination revealed generalized lymphadenopathy, decreased proprioception on the right hind limb but no other neurologic abnormalities. However, a complete neurological examination was difficult because the dog was severely stressed and confused. Further diagnostic examinations were planned, but the dog collapsed with pale mucous membranes, cold extremities, not palpable femoral pulse and muffled heart sounds.

Ultrasound showed a tumor in the spleen and hemorrhage to the abdominal cavity. The dog was euthanized.

Gross Pathology:

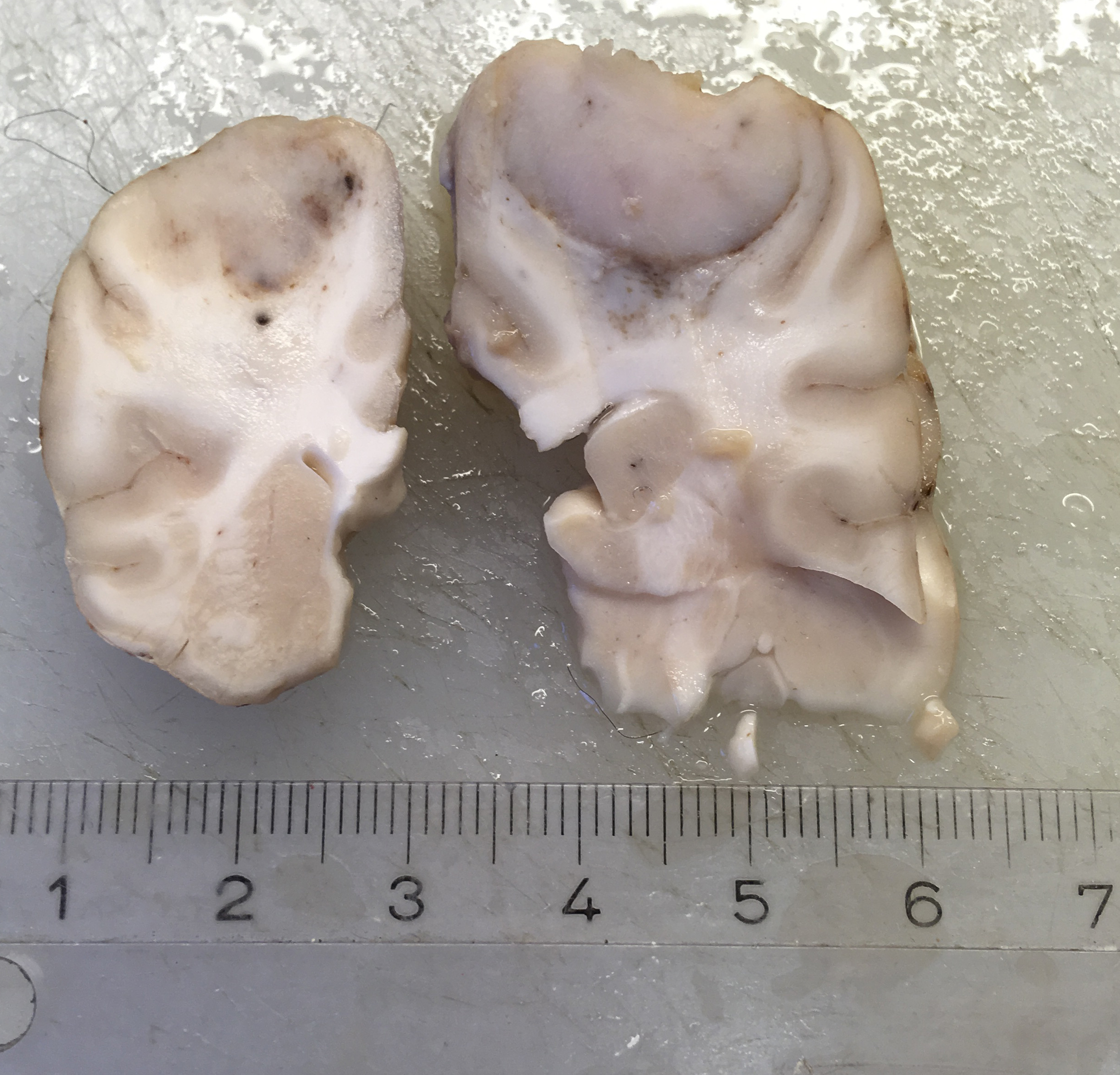

The carcass was pale. In the abdomen there was 600 mL non-coagulated blood. The source of the blood was identified as a ruptured splenic tumor, 3 cm in diameter. An approximately 8 cm large coagulum was present over the rupture.

The dog had several enlarged lymph nodes, e.g. the right iliofemoral and the hepatic lymph nodes were both 3 cm in diameter, and the right prescapular lymph node was 2 cm in diameter.

A 1.5 cm in diameter tumor was located dorsally in the left hemisphere of the cerebrum. The tumor was well demarcated ventrally, but rostral and caudal transition to normal brain tissue was poorly demarcated. The tumor had a light, red-grey cut surface with multifocal small dark foci (hemorrhage). The tumor compressed surrounding brain tissue.

Laboratory results:

None.

Microscopic description:

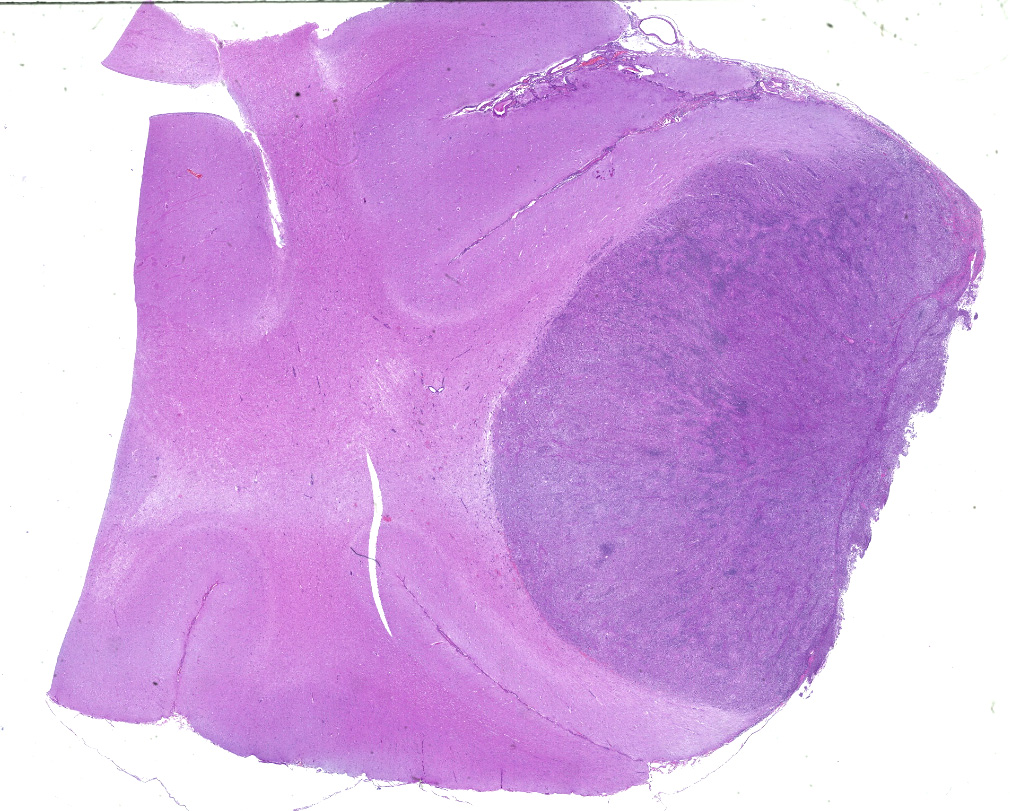

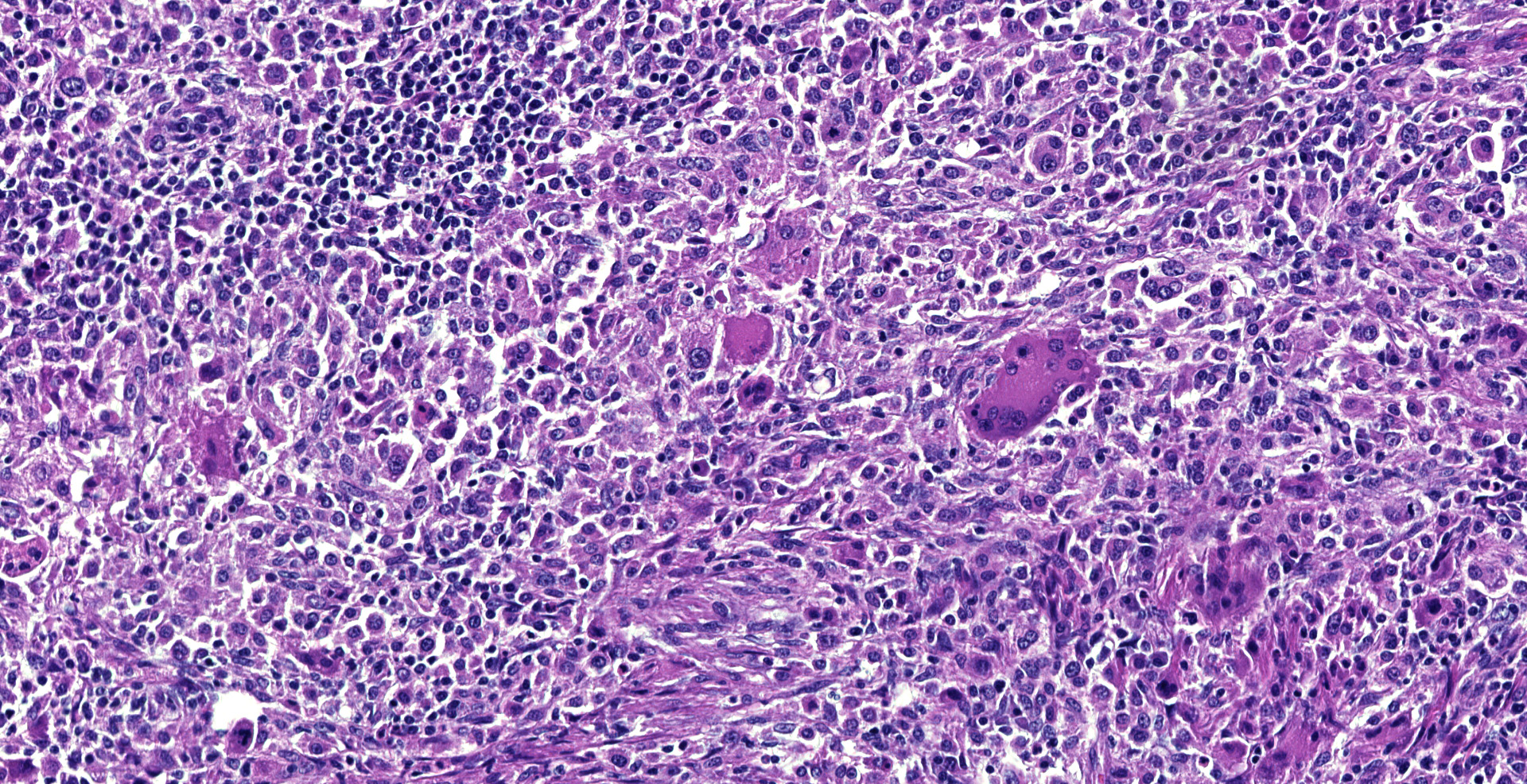

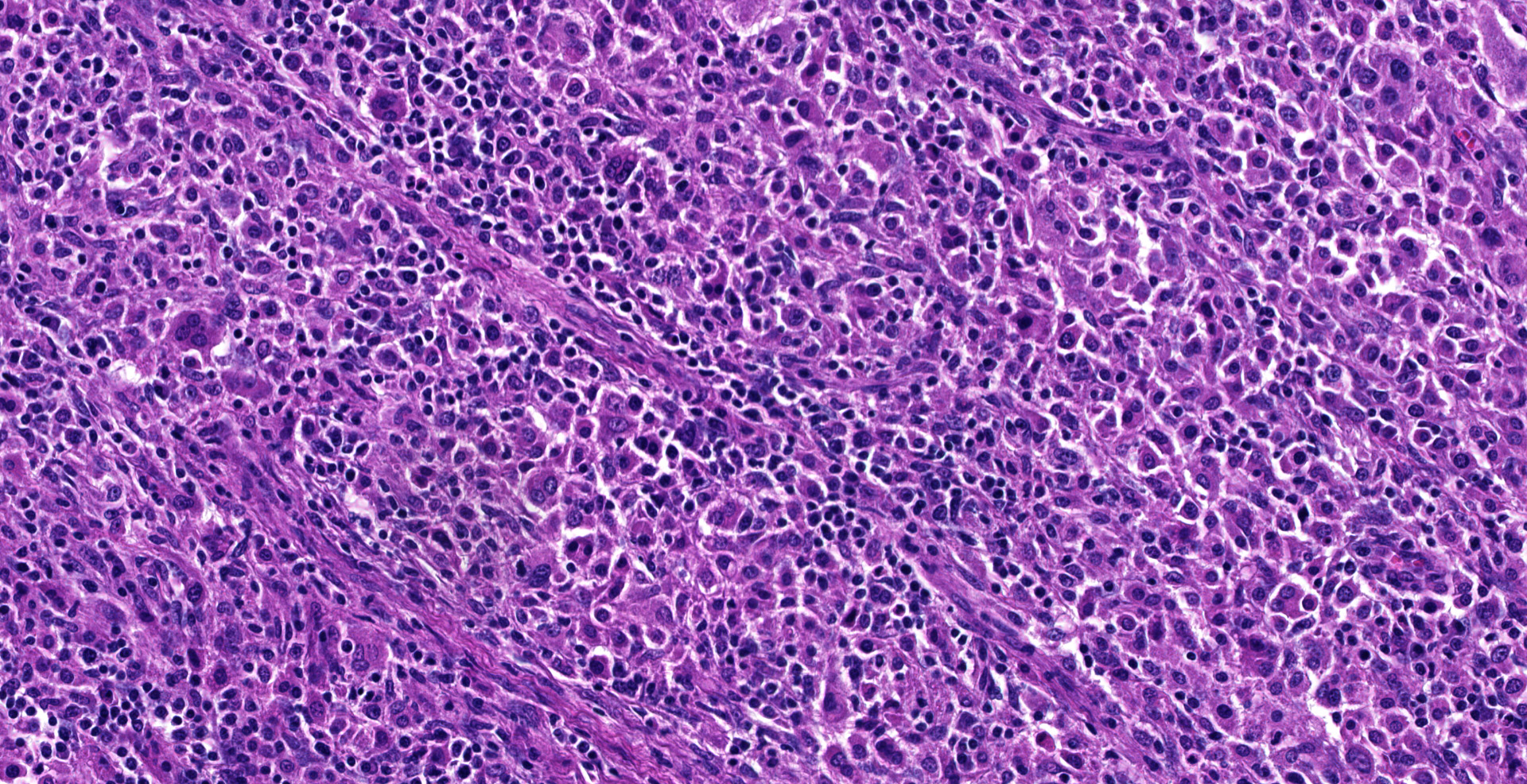

Dorsally in the left cerebral hemisphere, occupying grey and white matter and involving the overlying leptomeninges, there is a large (2 x 1.5 cm), densely cellular, moderately demarcated, infiltrative, non-encapsulated tumor. The tumor consists of sheets with closely packed round tumor cells, with some areas consisting of spindle cells. The tumor cells are pleomorphic, large with distinct borders, variable amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, a round or oval, often eccentric nucleus with coarsely stippled chromatin and 1-3 medium sized to large basophilic nucleoli. There is severe anisocytosis and anisokaryosis and multiple large multinucleated tumor cells and scattered uni- or multinucleated cells with karyomegaly. There are 4 mitotic figures per 10 HPF. In the periphery, there is infiltrative growth, especially along vessels. In the leptomeninges, the tumor cells infiltrate some distance from the main mass. In one of the sections there are multifocal necrotic areas infiltrated by neutrophils. Multifocally in the tumor and associated with vessels, there are infiltration of numerous well-differentiated lymphocytes and some plasma cells. Peri-tumoral brain tissue was compressed with edema, multifocal hemorrhages and prominent vessels.

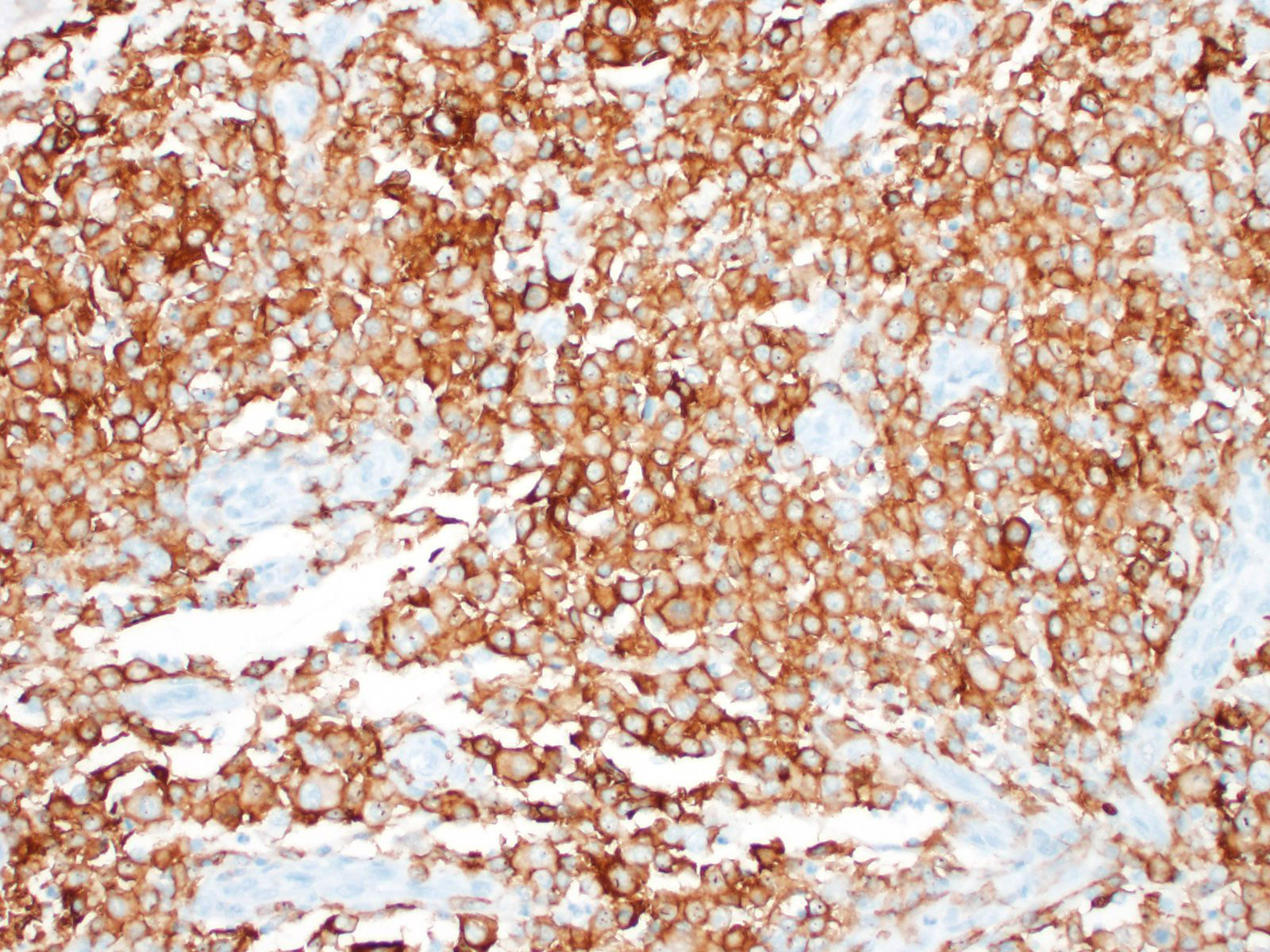

Immunohistochemical investigation showed that the tumor cells were CD18 positive. The lymphocyte population was composed of both CD3 and CD79 positive cells, thus a mixture of T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes.

In enlarged lymph nodes and the ruptured splenic tumor, there was an infiltrative growth of medium sized, relatively homogeneous lymphoid cells that effaced normal tissue architecture, diagnosed as lymphoma.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Brain: histiocytic sarcoma

Contributor's comment:

The present case is an example of localized, primary central nervous system (CNS) histiocytic sarcoma in a 9 years old female Flat Coated Retriever dog.

Histiocytic sarcoma is a malignant tumor. It is one of several histiocytic diseases that may occur in dogs and cats, a group of proliferative diseases that include lesions thought to be reactive inflammatory lesions, and benign and malignant tumors. The diseases are divided in two groups based on cell of origin; diseases of Langerhans cell (LC) origin and diseases of interstitial dendritic cell (DC) or macrophage origin. The first group, the diseases of LC origin, include canine cutaneous histiocytoma, canine cutaneous LC histiocytosis and feline pulmonary LC histiocytosis. The second group, of DC or macrophage origin, is again divided in two groups; the histiocytic sarcoma complex which includes several distinctive histiocytic sarcoma syndromes, and the canine reactive histiocytosis which include cutaneous histiocytosis and systemic histiocytosis.6

Histiocytic sarcomas are histologically composed of sheets of large, pleomorphic, mononuclear and multinucleated giant cells usually with marked atypia. Some lesions may also consist of spindle shaped cells, either alone or mixed with the other cell type. CNS histiocytic sarcoma also commonly contain large numbers of mixed inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells).6 All of these morphologic criteria were met in the present case and the tumor cells were confirmed CD18 positive by immunohistochemistry.

The Flat Coated Retriever is one breed predisposed to histiocytic sarcomas, other predisposed breeds are the Bernese Mountain dogs, Rottweilers and Golden Retrievers, however the disease may occur in any breed.6 Miniature Schnauzers have also been suggested to be predisposed to the disease.4

Histiocytic sarcomas may be localized or disseminated. The primary lesion may be solitary or multiple within an organ, and may occur in many different organs, e.g. spleen, lymph node, bone marrow, CNS, skin and subcutis, and periarticular or articular tissues.6

CNS involvement in histiocytic sarcoma may arise as a primary location or as a result of metastasis from another location.6 Although DCs, the cells of origin, may be present in diseased brain tissue, they are not present in normal steady state brain parenchyma, however they do exist in the meninges and choroid plexus.2 The CNS histiocytic sarcoma usually present as a subdural focal mass, however diffuse meningeal infiltrates may also occur.6 Although the brain tumor in the present case extended deep into the brain tissue, it infiltrated (and likely originated from) the leptomeninges. In some slides, neoplastic meningeal infiltrates extended deep in sulci next to the tumor.

As reviewed by Moore in 2014, CNS histiocytic sarcomas has not been shown to metastasize extracranially.6 In a case series describing histiocytic sarcoma with CNS involvement in 19 dogs, 15 of the dogs had histiocytic sarcoma restricted to the CNS and in 4 dogs the CNS involvement was considered as a part of a disseminated multiorgan process.5 Another study examined the histochemical and immunohistochemical characteristics of primary intracranial canine histiocytic sarcomas of 23 dogs.10 All cases were considered to be the localized form, although the study was based on only 3 autopsies while the remaining 20 dogs were diagnosed using biopsy material. Tumors located in the brain may be found in different areas of the brain,5,10 and in the spinal cord, they may be located in any spinal cord segment.5 There are also case reports describing CNS histiocytic sarcoma together with solitary pulmonary lesions.1,3

The dog also had moderate lymphadenomegaly and a ruptured mass in the spleen, the latter being the origin of hemoabdomen. These latter lesions had a morphology consistent with lymphoma, and it was concluded that the dog had two tumor types, both a primary localized CNS histiocytic sarcoma and a multicentric lymphoma in the spleen and lymph nodes. No metastasis from the brain lesions consistent with malignant histiocytes could be detected in any other tissues examined histologically. The lymphocytic infiltration in the brain tumor was a mixture of B- and T-lymphocytes, interpreted as reactive lymphocytic infiltration, and not metastasis of lymphoma from the lymph nodes or spleen to the CNS.

As a differential diagnosis, another lesion consisting of histiocytic cells together with other inflammatory cells that may present as a single space-occupying lesion is the focal form of granulomatous meningoencephalitis (GME). This form of GME is most commonly located within the white matter of the cerebrum, cerebellum, caudal brainstem or cervical spinal cord, but may also be observed in grey matter. The leptomeninges and choroid plexus may also be involved.7 It remains controversial whether the focal form of GME represents an immunoproliferative process or a neoplasia.11 The severe atypia in the present case, however, lead to the diagnosis of a cerebral histiocytic sarcoma rather than the focal form of GME.

Contributing Institution:

Norwegian University of Life Sciences

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

PO Box 8146 Dep

0033 Oslo

Norway

JPC diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Histiocytic sarcoma, flat coated retriever, canine.

JPC comment:

The contributor summarizes the topic succinctly, and correctly highlights many important points about the disease. In the human literature, there have been very few cases of primary CNS histiocytic sarcoma, with all histiocytic sarcomas comprising less than 1% of all hematolymphoid neoplasms.12 According to the most recent WHO classification of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues (2017), a diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma may be made only when there is expression of one or more histiocytic markers, which include CD163, CD68, or lysozyme, with concurrent lack of expression of CD1a, langerin (Langerhan cells), CD21, CD35 (follicular dendritic cells), CD13, or MPO (myeloid cells).9 While veterinary diagnoses of histiocytic sarcomas are not in doubt, rarely is immunohistochemical staining performed to rule out other neoplasms of histiocytic origin.

The most recent case report of primary CNS histiocytic sarcoma in humans described a diffuse leptomeningeal neoplasm, filling the subarachnoid space of the brain and spinal cord, with few foci of infiltration into neuroparenchyma. This case had no lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or cutaneous lesions, increasing the likelihood that this histiocytic sarcoma arose in the leptomeninges as a primary pathology.12

The contributor posited one potential differential diagnosis (GME), but others may include Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Rosai-Dorfman disease, and juvenile xanthogranuloma. Histiocytes in Langerhans cell histiocytosis typically exhibit minimal nuclear atypia, are positive for CD1a, and are accompanied by eosinophilic infiltration. Rosai-Dorfman disease is characterized by emperipolesis, infiltration by numerous plasma cells, and histiocytes with abundant amphophilic cytoplasm, round nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Juvenile xanthogranuloma, there is significant lipidization of histiocytes, also with minimal atypia. Other neoplasms that can be distinguished from histiocytic sarcoma through morphology and immunohistochemistry include glioblastoma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma.8

References:

- Barrot AC, Bédard A, Dunn M. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion in a dog with a histiocytic sarcoma. Can Vet J. 2017;58:713-715.

- D'Agostino PM, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Anandasabapathy N, Bulloch K. Brain dendritic cells: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:599-614.

- Hicks J, Barber R, Childs B, Kirejczyk SGM, Uhl EW. Canine histiocytic sarcoma presenting as a target lesion on brain magnetic resonance imaging and as a solitary pulmonary mass. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1111/vru.12502

- Lenz JA, Furrow E, Craig LE, Cannon CM. Histiocytic sarcoma in 14 miniature schnauzers ? a new breed predisposition? J Small Anim Pract. 2017;58: 461-467.

- Mariani CL, Jennings MK, Olby NJ, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma with central nervous system involvement in dogs: 19 cases (2006?2012). J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:607-613.

- Moore PF. A Review of histiocytic diseases of dogs and cats. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:167-184.

- O'Neill EJ, Merrett D, Jones B. Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis in dogs: A review. Ir Vet J. 2005;58:86-92.

8. So H, Kim SA, Yoon DH, et al. Primary histiocytic sarcoma of the central nervous system. Cancer Res Treat. 2015;47(2):322-328.

9. Swerdlow SH, Campo

E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J (Eds):

WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues

(Revised 4th edition). IARC: Lyon 2017.

- Thongtharb A, Uchida K, Chambers JK, Kagawa Y, Nakayama H. Histological and immunohistochemical studies on primary intracranial canine histiocytic sarcomas. J Vet Med Sci. 2016;78:593-599.

- Vandevelde M, Higgins RJ, Oevermann A. Inflammatory diseases. In: Vandevelde M, Higgins RJ, Oevermann A eds. Veterinary neuropathology, essentials of theory and practice. 1st ed. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2012:48-80.

- Zanelli M, Ragazzi M, Marchetti G, et al. Primary histiocytic sarcoma presenting as diffuse leptomeningeal disease: Case description and review of the literature. Neuropathology. 2017;37(6):517-525.