Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 20

20 March, 2019

CASE IV: C9969-15 (JPC 4070611).

Signalment: 11 year old, male, castrated, Labrador retriever, Canis lupus familiaris, canine

History: The dog presented to referring veterinarians with hematuria and dysuria. A cystotomy was performed and calculi were removed. Several months later Rudy presented again with hematuria. He would also dribble small spots of blood from the preputial opening when not urinating. Otherwise, the dog was bright, alert and responsive. The dog was referred to the Atlantic Veterinary College teaching hospital for further work-up. A urethroscopy was performed. Approximately 1 cm from the tip of the penis and extending approximately 2 cm further up the urethra, the mucosal surface was roughened with irregular frond-like structures extending into the narrowed lumen. Small pinch biopsies were taken of the abnormal mucosal surface. A diagnosis of urethral urothelial (or transitional) cell carcinoma was made. A partial penile amputation and an urethrostomy at the level of the bulbourethral gland was performed. The amputated portion of the penis was submitted for histopathology.

Gross Pathology: A 7.5 cm long section of the distal penis (including the glans and the distal body of the penis) is submitted for examination. The length of the urethra was opened. The mucosal lining of the distal 3 cm of the urethra was mildly roughened. Several cross-sections through the entire penis were examined.

Laboratory results Presurgical complete blood count and serum biochemistry; mild abnormalities included:

| • ¢ RBC | 5.26 x 1012 /L | (normal range: 5.7 - 8.4 1012/L) |

| • ¢ Hemoglobin | 127 g/L | (normal range: 135 - 198 g/L) |

| • ¢ Hematocrit | 0.364 L/L | (normal range: 0.40 - 0.56 L/L) |

| • § ALT | 93 U/L | (normal range: 13 - 69 U/L) |

Mild anemia was attributed to mild, chronic blood loss. Mildly increased ALT may represent mild hepatocellular leakage or possibly normal variation in this individual.

Microscopic Description:

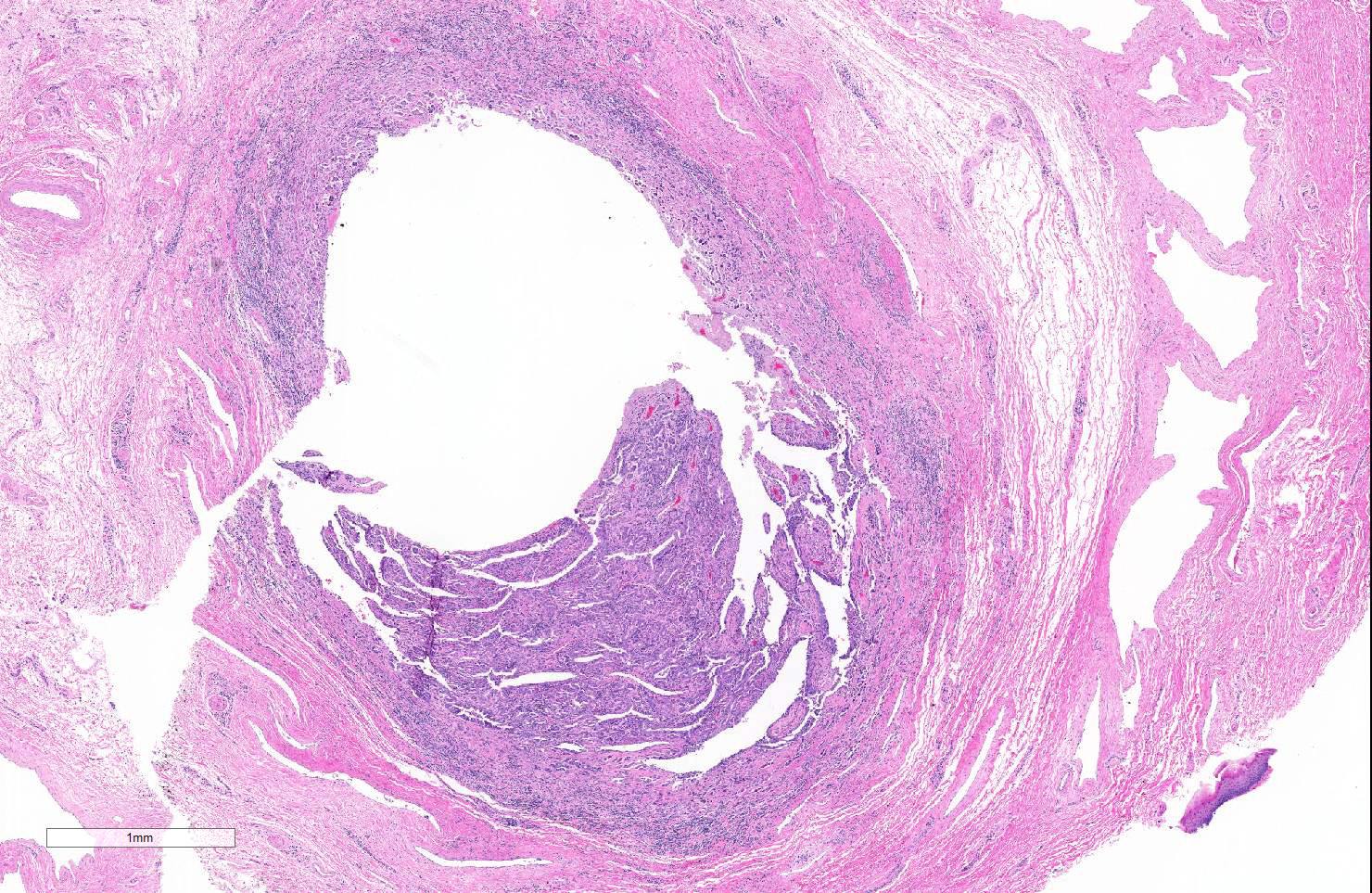

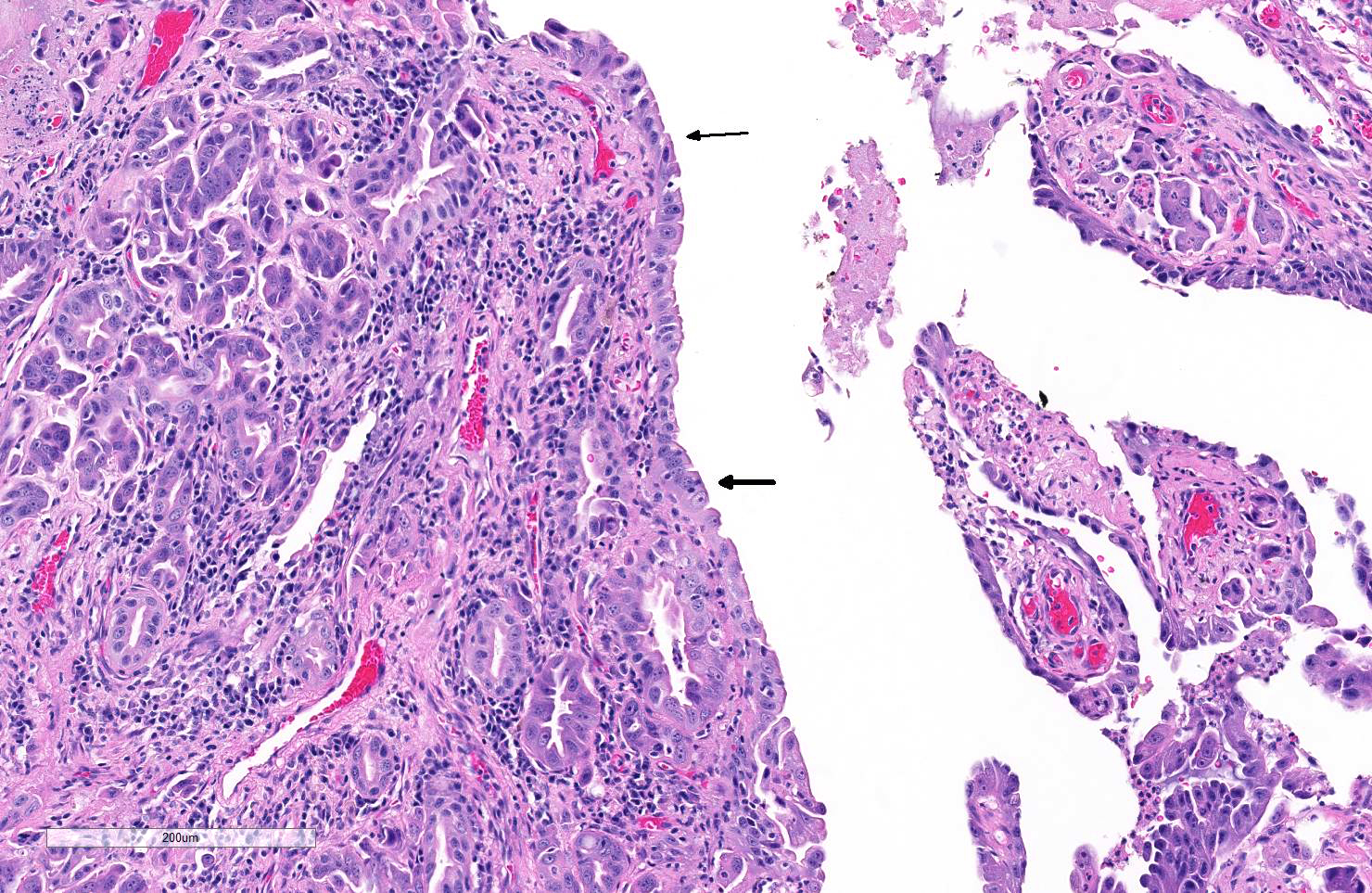

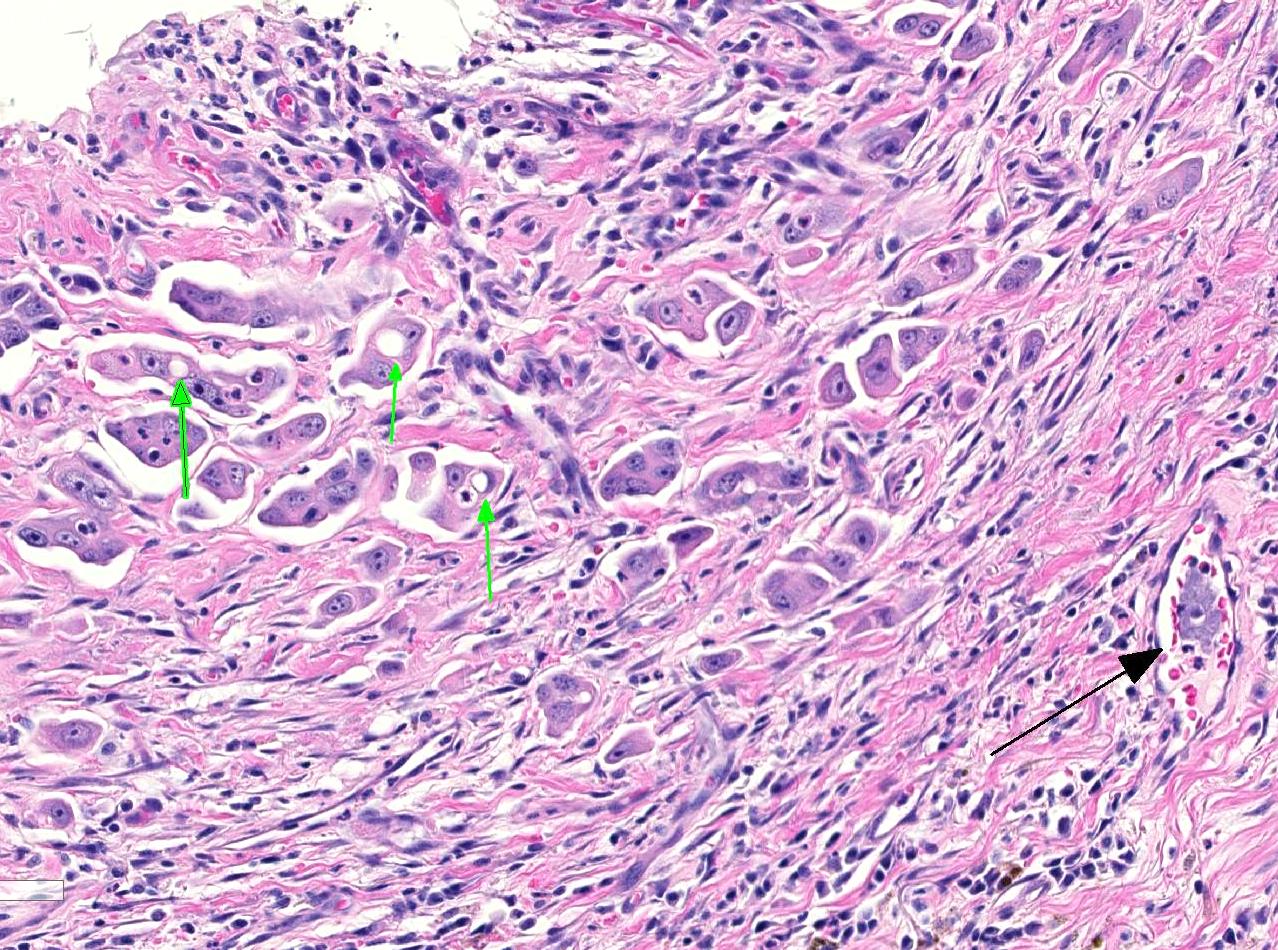

Microscopically, the urethral lumen is narrowed and the mucosa is irregularly thickened by an infiltrative, poorly defined epithelial tumor composed of many small nests, occasional small acini and few small papillary projections covered by large polygonal neoplastic epithelial cells. These infiltrates are supported by small amounts of dense fibrous stroma containing mild to moderate infiltrates of plasma cells, neutrophils, fewer lymphocytes and macrophages. The mucosal lining is extensively ulcerated and occasionally covered by small amounts of proteinaceous debris. Several layers of pleomorphic neoplastic epithelial cells partially line the urethral lumen in areas. Small clusters and scattered individual polygonal tumor cells frequently breach the mucosal basement membrane and infiltrate the underlying submucosa where they are accompanied by mild multifocal infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, few neutrophils, few small foci of hemorrhage and occasional macrophages rarely laden with hemosiderin. Neoplastic epithelial cells have medium to large, ovoid, nuclei with finely stippled chromatin, one to several, prominent nucleoli and moderate to large amounts of poorly defined, cytoplasm. Anisokaryosis is moderate to severe. Mitotic figures are present (7 per 10 HPF). Small clusters of neutrophils admixed with a few sloughed tumor cells are noted in the urethral lumen. Rarely, small clusters of polygonal cells resembling tumor cells are present within lymphatics and veins within the submucosa, the corpus spongiosum and the pars longo glandis (not present in all sections). The ovoid, discrete aggregate of dense, poorly cellular, collagen dorsal to the urethra represents the distal end of the os penis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Penis:

- Urethral urothelial (or transitional) cell carcinoma

- Mild to moderate, lymphoplasmacytic and neutrophilic, erosive, chronic, urethritis

Contributor’s Comment: The cause of hematuria and persistent blood dribbling from the penis of this dog was a urothelial (or transitional) cell carcinoma arising within the distal urethra. Ultrasound performed at the time of surgery revealed no abnormalities in the urinary bladder and no evidence of abdominal or retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement. Thoracic radiographs were also unremarkable. Occasional small microscopic clusters of putative tumor cells were noted within vascular structures in these sections. Despite the latter finding, 2 years after partial penile amputation and complete removal of the tumor, this dog is still alive and has exhibited no clinical signs indicative of metastatic disease (per recent discussion with the rDVM).

Primary urethral tumors are very rare in dogs. The vast majority of these tumors are malignant and most are urothelial cell carcinomas. Females are generally thought more commonly affected than males. The cause is unknown but a variety of chemical carcinogens have been associated with the development of lower urinary tract tumors in dogs.2 An association between chronic urethritis and urothelial tumors in females has also been shown.1 The latter is interesting as this male dog, also had a chronic history of urinary struvite calculi. Urothelial cell carcinomas in the lower urinary tract generally occur in older dogs which often present with hematuria and dysuria. References generally report that metastasis is seen in approximately 30% of cases; regional lymph nodes are the most common site. Approximately 1/3 of dogs with urethral tumors also have urothelial cell carcinomas in the urinary bladder. When present in both sites, affected dogs tend to have a much poorer prognosis and significantly shorter survival times.1,2 One retrospective study on canine lower urinary tract tumors reported that the longest survival times (median of 365 days) were achieved in dogs with no evidence of metastasis at the time of surgery, that had a solitary carcinoma located in either the urinary bladder or the urethra, and in which complete resection was achieved.2

Contributing Institution:

Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island / www.upei.ca

JPC Diagnosis: Penile urethra: Transitional cell carcinoma

JPC Comment: Transitional cell (or urothelial carcinoma)as account for approximately 2% of cancer in the dog. It is the most common neoplasm of the bladder, and the majority are high-grade neoplasms. It is primarily seen in older dogs between the ages of 9 and 11, and most tumors are considered high-grade neoplasms. Scottish terriers have an increased breed predisposition being 18-20X more likely to develop this tumor than other breeds. The trigone is the site of most tumor development, although the prostatic urethra and lower areas of the urethra (as seen in this case) are also commonly affected. Grossly, most neoplasms in the bladder are solitary, although they may cover a large region of the bladder making resection impossible. 1

Histologically, most tumors are readily diagnosed histologically, especially if an adequate sample is obtained. One of the more diagnostic features is the presence of Melamed-Wolinska bodies, which impart a signet ring appearance to neoplastic cells and are commonly seen in these tumors. These bodies often stain positively for uroplakin (a commonly used immunohistochemical marker for TCC).1

Tumor growth patterns often impact on grading schemes. While most neoplasms are infiltrative indicating a high-grade, non-infiltrative neoplasms (carcinoma in situ) is occasionally seen or seen at the periphery of infiltrative lesions. Tumors may also be papillary or non-papillary, although this particular feature has not been identified as predictive of future behavior. 1

Invasive TCC is also extremely prone to widespread metastasis with studies demonstrating a 50-90% rate, most often to the lungs and lymph nodes. Approximately 75% are staged at T2 under the TNM system , and an addition 20% at stage 2 with invasion of adjacent organs or tissues. Cutaneous metastasis has been reported to occur in up to 10% of cases. While the presence of urethral involvement does not appear to be significantly related to the presence or absence of metastatic disease, concurrent presence of TCC within the bladder and urethra is associated with the shortest survival times.1

As the prostatic urethra is a common site of urothelial carcinoma and local invasion, the diagnosis of prostatic carcinoma should likely include immunohistochemistry for uroplakin to rule out other forms of carcinoma. Uroplakin (uroplakin III) is an excellent marker for urothelium but may be positive in normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic urothelium. In the dog, staining is seen primarily at the surface of cell membranes in the dog and is often not uniform throughout neoplasms.1 Other immunohistochemical markers that have been shown to have utility in the diagnosis and prognosis for human and canine TCCs include cytokeratin 7 and cyclooxygenase-2. It should be noted that there is often a loss of uroplakin and cytokeratin expression in high-grade carcinomas, especially infiltrative tumors. 3

References:

- Meuten DJ, and Meuten TLK. Tumors of the Urinary System. In: Meuton DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals, 5th ed. Ames, Iowa; Wiley Blackwell; 2017:

- Norris AM, Laing EJ, Valli VE, et al. Canine bladder and urethral tumors: A retrospective study of 115 cases (1980-1985). J Vet Int Med. 1992: 145-153.

- Sledge DG, Patrick DJ, Fitzgerald SD, Xie Y, Kiupel M. Difference in expression of uroplakin III, cytokeratin 7, and cyclooxygenase-2 in canine proliferative urothelial lesions of the urinary bladder. Vet Pathol 2015; 2(1):74-82