CASE IV:

Signalment:

4-month-old, female intact, Mustela putorius furo, ferret.

History:

A mass was noted in the caudal abdomen and the ferret was euthanized. Coronavirus was suspected.

Gross Pathology:

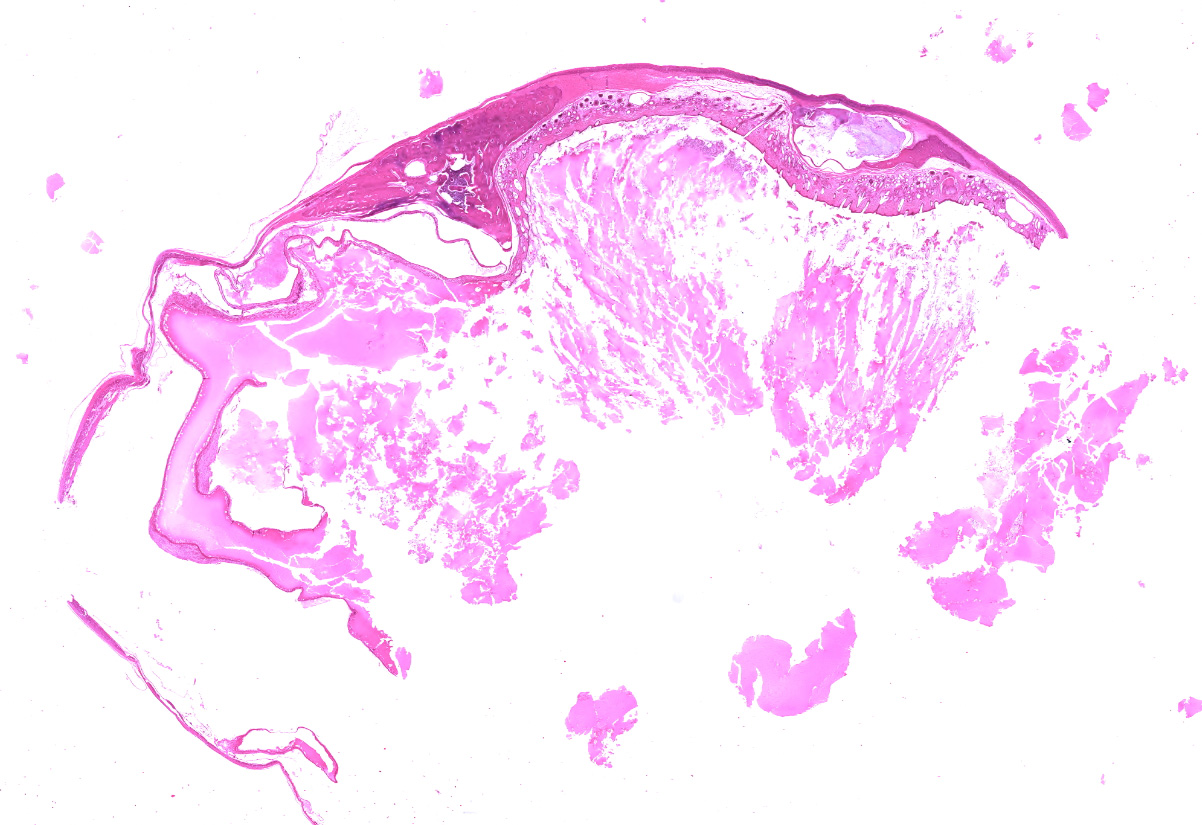

The adrenal gland is markedly enlarged (up to 3x). The normal parenchyma is extensively replaced by multiple cysts filled with serous fluid, regions of haired skin, and bone/cartilage, which markedly compress a thin rim of adrenal cortex.

Laboratory Results:

None submitted.

Microscopic Description:

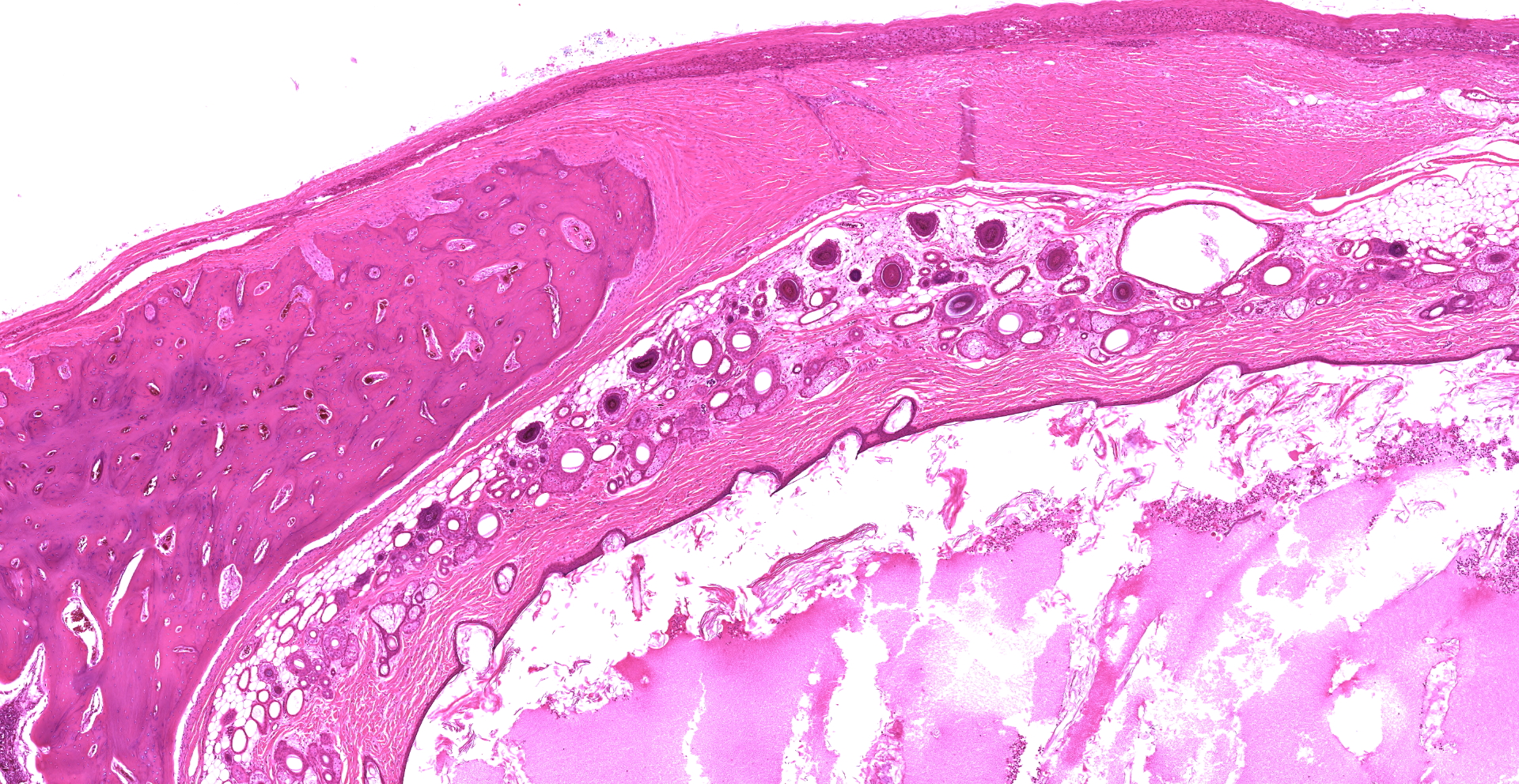

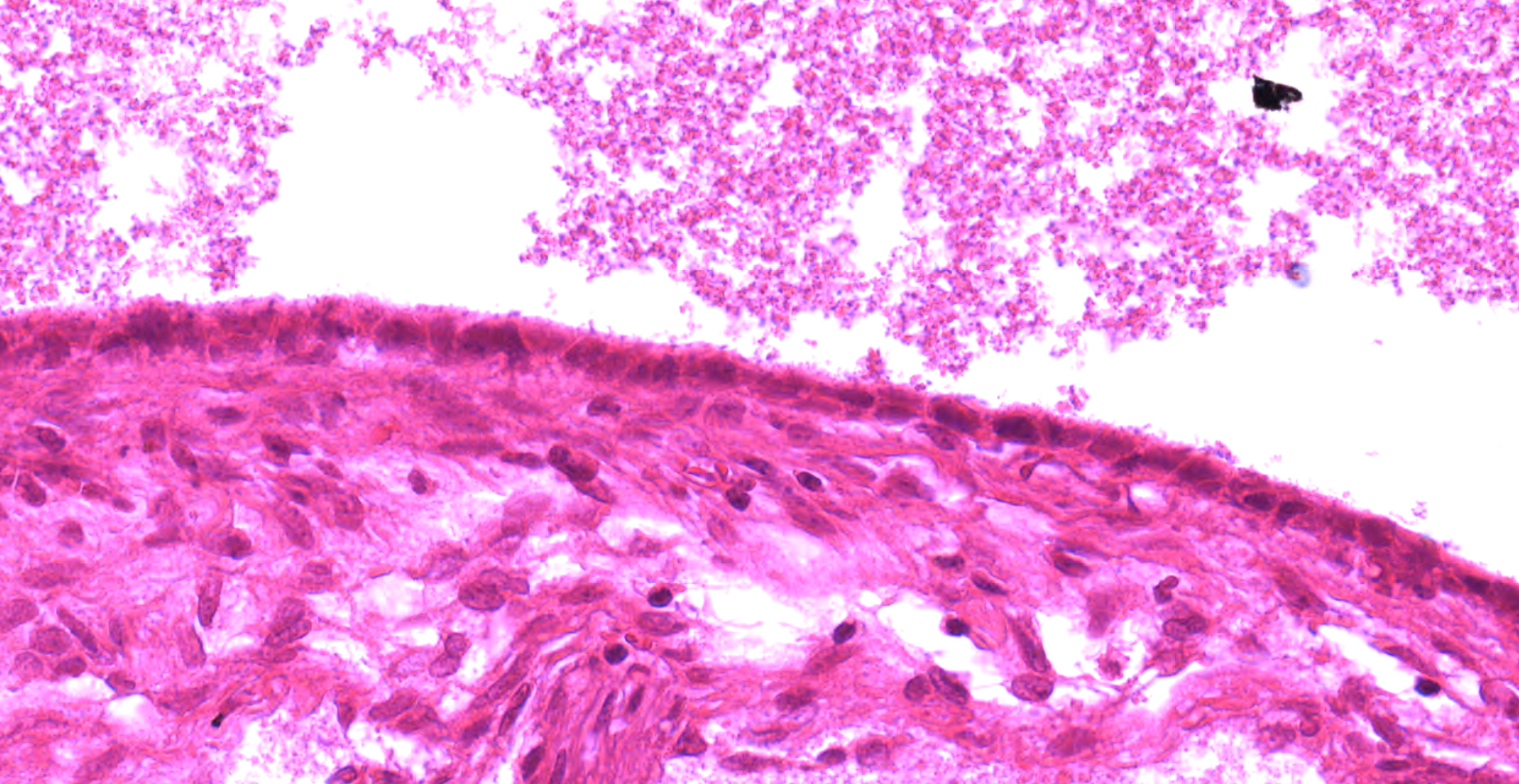

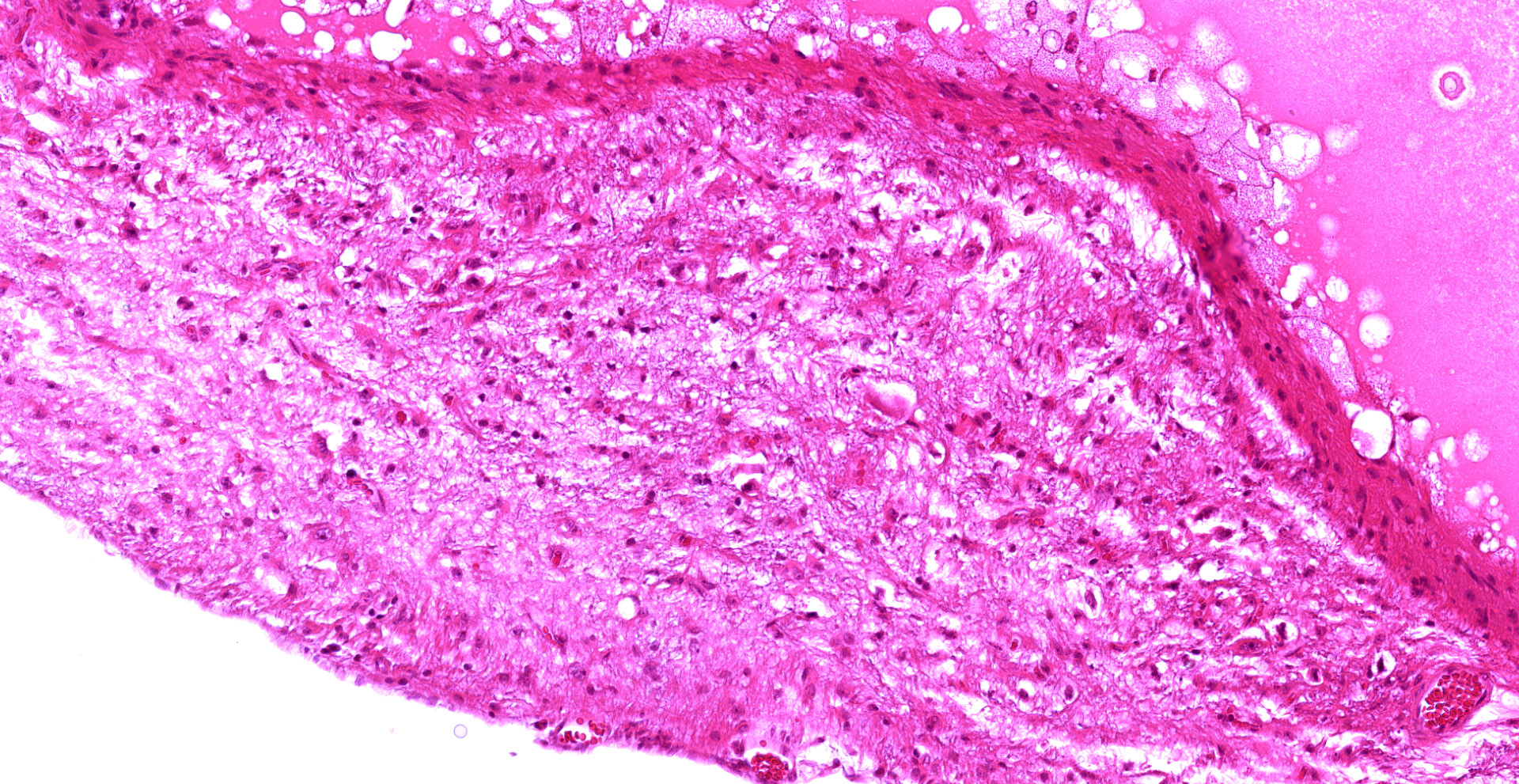

The adrenal gland is extensively effaced and replaced by a well demarcated, expansile, encapsulated population of neoplastic cells derived from the ectoderm, mesoderm, and (suspected) endoderm. Ectodermal components occupy 60% of the mass and consist of attenuated stratified squamous epithelium that lines a large cystic space filled with lamellated keratin, eosinophilic fluid, degenerate neutrophils, and foamy macrophages. The underlying dermis contains dilated hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and dilated apocrine glands overlying sheets of well-differentiated adipose tissue. A second type of cyst occupying 10% of the mass is lined by an attenuated simple columnar to cuboidal ciliated epithelium with rare goblet cells and is filled with eosinophilic and basophilic flocculent material, foamy macrophages, and karyorrhectic debris. This mass markedly compresses a thin rim of remnant adrenocortical cells characterized by sheets of eosinophilic foamy polygonal cells with central round nuclei. Mesodermal components occupy 30% of the mass and consist of large islands of mature trabecular bone lined by a single layer of osteoblasts surrounded by bone marrow, rare partially mineralized islands of cartilage, and dense fibrous connective tissue.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Adrenal: teratoma, ferret (Mustela putorius furo)

Contributor's Comment:

Teratomas are germ cell neoplasms derived from at least two of the three embryonic germ layers: the ectoderm (that gives rise to epithelia, adnexa, and the nervous system), the mesoderm (connective tissue, musculoskeletal, urogenital, and cardiovascular system) and the endoderm (gastrointestinal epithelium, respiratory glandular epithelium, liver, and pancreas).1 In domestic animals, the majority of teratomas occur in the gonads but interestingly in ferrets, teratomas most commonly arise within the adrenal gland.5 In one report of adrenal teratomas in four ferrets, the majority of neoplasms contained tissues form all three germ cell layers including bone, bone marrow, cartilage, teeth, haired skin, brain tissue, peripheral nerves, respiratory epithelium, and gut epithelium. They reported that teratomas were rarely bilateral and rarely metastasized to the mesenteric lymph node.14 The histogenesis of extra-gonadal teratomas is unclear; however, neoplastic cells are thought to arise from diploid pluripotent precursor cells.13 In addition to ferrets, adrenal teratomas have been reported in humans, an ox, and a rat.6,7,11

In the ferret, gross differentials for an adrenal mass include (from most to least common): adrenocortical hyperplasia, carcinoma, adenoma, pheochromocytoma, leiomyoma/sarcoma, spindle cell sarcoma, and neuroblastoma.2 Adrenal teratomas are not hormonally active. They are therefore, easy to clinically differentiate from adrenocortical tumors and/or hyperplasia, which produce excess estrogen and estrogen precursors. The excess estrogen induces the telltale signs of adrenal-associated endocrinopathy including bilaterally symmetric truncal alopecia, pruritis, vulvar swelling, inappropriate sexual behavior (neutered males), and dysuria (males).9 Histologically, while differentiating between adrenocortical hyperplasia vs carcinoma vs adenoma is challenging, distinguishing these entities from teratomas is straightforward.

In this case, while there is clear differentiation into ectodermal and mesodermal components, suspected endodermal components are limited to the dilated cyst lined by ciliated columnar to cuboidal epithelium with goblet cells, which may represent some form of respiratory epithelium. Given that only two germ cell layers are confirmed in this case, a differential diagnosis to consider is a dermoid cyst. Dermoid cysts are defined as mature teratomas composed predominantly of a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium variably filled with lamellated keratin and associated with hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands. Less prominent components of the mass may include bone, cartilage, fat, or muscle.8 Teratoma remained the favored diagnosis in this case given that adrenal teratomas are a well-established entity in ferrets; adrenal dermoid cysts are

rarely reported in the literature and have not been described in the ferret.

Contributing Institution:

Michigan State University

JPC

Diagnosis:

Adrenal gland: Teratoma.

JPC Comment:

This case represents a classic presentation of this entity in ferrets, while the gonads are the most commonly affected location in other domestic species.

Reports of neoplasms likely to be teratomas (or dermoid cysts) have been found in ancient literature, with the earliest likely description of a teratoma being found on a Babylonian cuneiform papyrus dating to 2,000 B.C. Galen also described a lesion likely a dermoid cyst during the first century A.D. The first unequivocal description of an ovarian dermoid cyst was published by Johannes Scultetus in 1659, describing the results of an autopsy of a woman with an ovarian tumor. However, Leblanc first used the term "dermoid cyst" while describing a lesion in the base of a horse's skull, emphasizing its gross resemblance to skin. The first to describe the microscopic features of dermoid cysts was Kohlrausch in 1843, who noted their histologic resemblance to skin. The term "teratoma" (teras; Greek for "monster") was first introduced by Rudolf Virchow in 1863, in the first edition on his

book on tumors. As noted by the contributor, both terms are still in use today, with dermoid cysts restricted to dermal and epidermal elements (both composed of ectoderm) while teratomas also comprise mesodermal and endodermal elements.10

During the Middle Ages, teratomas were thought to arise due to sins of the flesh, which is unsurprising given their often striking gross features. This notion was further supported in that the lesion often resembled a deformed fetus, strengthening suspicion that teratomas were the result of wicked sins such as fornification with the devil, sexual fantasies and dreams, and witchcraft. One account describes "?a male child developed so completely in the thigh of its father, ?as to permit being brought into the world alive by an operation at the end of nine months." The report went on to discuss the need for baptism in such cases. Multiple theories have subsequently arisen over the following centuries to their cause, including a prerequisite of sexual relations, consumption of human teeth and bones, in situ pregnancies induced by misery and disgrace, a parasitic fetus, and parthenogenesis.10

In companion animals, teratomas are most commonly benign but can also be malignant with distant metastasis of one or more of the components. The histogenesis of these neoplasms likely varies depending on the site of origin. Gonadal teratomas thought to develop from parthenogenetic development

of haploid post-meiotic germ cells or diploid premeiotic germ cells whereas extragonadal

teratomas likely originate from undifferentiated diploid pluripotent progenitor cells. Although the incidence of extragonadal teratomas is very low, they are not restricted to the adrenal gland. Non-adrenal extragonadal teratomas are typically congenital, found along the midline, and have been reported in humans, ducks, rabbits, rats, mice, an ox, a kitten, a sheep, a calf, and a blue heron.14

Interestingly, the first case of malignant testicular teratoma (i.e. testicular teratocarcinoma) in a ferret was recently reported in a 7 month old ferret that initially presented for an enlarged left testicle. The testicular mass was later found to be a teratoma with all three germ cell lines. The ferret subsequently developed an abdominal mass initially suspected to be an adrenocortical tumor and was euthanized following a decline in health over the following weeks. Upon histologic examination of the tissues, metastasis of the poorly differentiated epithelial component were identified in multiple tissues, including the urinary bladder, ureters, prostate, pelvic fat, abdominal and thoracic lymph nodes, kidney, and lung.3

Participants discussed the multitude of tissues derived from the embryonic germ cell layers, which were previously outlined in 2013 WSC#8, case 3 and are reflected in Table 1.

|

Table 14,12 |

||

|

Ectoderm |

Mesoderm |

Endoderm |

|

|

|

References:

- Agnew DW, MacLachlan NJ. Tumors of the genital systems. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2017:690-698.

- Avallone G, Forlani A, Tecilla M, et al. Neoplastic diseases in the domestic ferret (Mustela putorius furo) in Italy: classification and tissue distribution of 856 cases (2000-2010). BMC Vet Res 2016, 12(1):275.

- Fiddes KR, Murray J, Williams BH. Testicular Teratocarcinoma in a Ferret (Mustela putorius furo). J Comp Pathol. 2020;181:63-67.

- Foster RA. Male reproductive system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017:1210-1211.

- Fox JG, Muthupalani S, Kiupel M, Williams B. Neoplastic diseases. In: Fox JG, Marini RP, eds. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2014:595.

- Ladds PW, Russell P, Foster RA: Adrenal teratoma in an ox. Aust Vet J 67:464?465, 1990.

- Lam KY, Lo CY. Teratoma in the region of the adrenal gland: a unique entity masquerading as lipomatous adrenal tumor. Surgery 126:90?94, 1999.

- Mensi DW. Cytologic findings in two cases of dermoid cysts with malignant transformation. Diagnostic Cytopathology 2011, 39(12):919-923.

- Miller CL, Marini RP, Fox JG. Diseases of the Endocrine System. In: Fox JG, Marini RP, eds. Biology and Diseases of the Ferret. 3rd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2014:377-380.

- Pantoja E, Noy MA, Axtmayer RW, Colon FE, Pelegrina I. Ovarian dermoids and their complications. Comprehensive historical review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1975 Jan;30(1):1-20.

- Schardein JL, Fitzgerald GE. Teratoma in a Wistar rat. Lab Anim Sci 27:114, 1977

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:377-378.

- Wagner H, Baretton GB, Scheiderbanger K, Nerlich A, Bise K, Lohrs U. Sex chromosome determination in extragonadal teratomas by interphase cytogenetics: clues to histogenesis. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 17:401?412, 1997.

- Williams BH, Yantis LD, Craig SL et al. Adrenal teratoma in four domestic ferrets (Mustela putorio furo). Path. 2001, 38:328-331.