Signalment:

Gross Description:

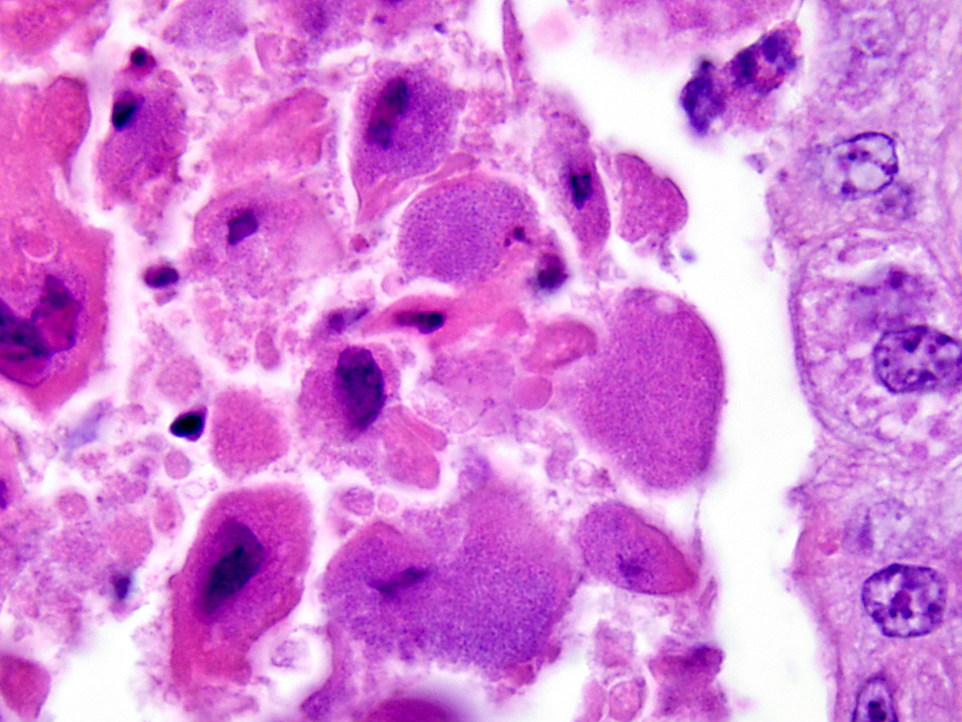

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Brucellosis is caused by small gram-negative bacilli of the genus Brucella; these bacteria are facultative intracellular organisms. The organism lacks many of the typical virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria and how the organism resists phagocytic degradation and is able to replicate within professional and non-professional phagocytes is poorly understood. There are multiple species within the genus and include: B. abortus biovars 1-9 (cattle), B. sues biovars 1-5 (swine), B. obis (sheep), B. melitensis biovars 1-3 (sheep and goats), B. can is (dog), B. neotomae (rodents), and species that infect pinnipeds and cetaceans. B. abortus, B. sues and B. melitensis are further subdivided into biovars but contrary to the species name, these organisms can also cause disease in numerous other domestic and wild animal hosts and these are the common species infecting man. B. can is and marine Brucella species have also rarely been associated with disease in man, whereas B. obis and B. neotomae are recognized to only infect sheep and rodents, respectively.

Brucellosis in animals is characterized by third trimester abortion with necrotizing placentitis, retained placentas and metritis, weak calves, mastitis, arthritis/hygromas/bursitis, and in males, orchitis/epididymitis and seminal vesiculitis. The disease in susceptible domestic animal populations has significant economic consequences due to calf loss, infertility, decreased milk production and disease regulatory consequences. Infected animals can eventually become resistant but could still act as intermittent shedders that serve as a reservoir of infection within the herd. Transmission is usually through ingestion or contamination of mucous membranes after exposure to infected fetuses, fetal membranes or contaminated body fluids. Venereal transmission occurs with B. suis, B. obis and B.canis but is uncommon with B. abortus or B. melintensis. Abortions also can occur after vaccination of pregnant females with live vaccine strains.

Brucellosis in man has multiple synonyms such as undulant fever and Malta fever. In countries where the disease is common, infection in man is normally acquired by ingestion of contaminated dairy products or exposure to infected animal reproductive tissues and fluids. Infection can result from exposure to the agent after ingestion, inhalation, through open wounds, accidental injection when vaccinating animals, and congenitally from infected mothers. Effective animal disease control programs and pasteurization of dairy products are major contributors in the low rates of human infections in modern societies. Laboratory personnel, veterinarians and agricultural and slaughterhouse workers are at higher risk for acquiring infections. Laboratory personnel are extremely vulnerable and can readily be exposed if safety precautions are not utilized. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (CDC BMBL) recommends strict adherence to BSL-3 safety practices in conjunction with sound laboratory techniques when culturing the organism. The infectious dose for man varies depending on the species. In man, only 1-10 CFU of B. melitensis can cause disease. Reported infectious doses for immune-competent people with the following species are: B. sues (1000-10,000 CFU), B. abortus (100,000 CFU) and B. can is (greater that 1,000,000 CFU).

Acute disease in man usually results in incapacitating flu-like illness, cyclic fevers, gastrointestinal upsets, epididymitis/orchitis, and in severe cases, CNS or endocardial disease. Chronic infections can manifest as chronic fatigue-like syndromes, depression, arthritis, endocarditis, hepatitis, cholecystitis, meningitis, uveitis, and osteomyelitis. Mortality rate is less than 5%. Treatment involves long term antibiotic therapy and currently, there is no human vaccine.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Fetal death and abortion are attributed to placental disruption and endotoxemia; fibrinous bronchopneumonia, pleuritis and pericarditis are seen in the fetus. In addition to Arcanobacterium pyogenes, B. abortus is the most common cause of bacterial fetal pneumonia. The bacterial infection induces hypoxia through placental inflammation, and this disruption of the placenta induces a breathing response in the fetus, and death is due to aspiration of the amniotic fluid.(3,5,14) Typical gross placental lesions include extensive cotyledonary necrosis; intercotyledonary edema with a tough, yellow to gray, leathery surface; necrosis and inflammation of the placental arcades; and inflammation of the maternal septa, leading to placental interlocking and retained placenta.(5) Brucella abortus is also commonly associated with bursitis in horses, known colloquially as poll evil and fistulous withers.(13)

References:

2. Beja-Pereira A, Bricker B, et al. DNA genotyping suggests that recent brucellosis outbreak in Greater Yellowstone Area originated from elk. J Wild Dis. 2009;45:1174-1177.

3. Foster RA. Female reproductive system and mammary gland. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis for Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:531.

4. Kreeger TJ, Cook WE, et al. Brucellosis in captive Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) caused by Brucella abortus biovar 4. J Wild Dis. 2004;40:311-315.

5. Lopez A. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleurae. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis for Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:1113.

6. Meyer M, Meagher M. Brucellosis in free ranging bison (Bison bison) in Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Wood Buffalo National Parks: a review. Letter to editor. J Wild Dis. 1997;31:579-598.

7. Olsen SC, Holland SD. Safety of revaccination of pregnant bison with Brucella abortus strain RB51. J Wild Dis. 2003;39:824-829.

8. Rhyan JC, Gidlewski T, et al. Pathology of brucellosis in bison from Yellowstone National Park. J Wild Dis. 2001;37:101-109.

9. Rhyan JC, Holland SD, et al. Seminal vesiculitis and orchitis caused by Brucella abortus biovar 1 in young bison bulls from South Dakota. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1997;9:368-374.

10. Rhyan JC, Quinn WJ, et al. Abortion caused by Brucella abortus biovar 1 in free ranging bison (Bison bison) from Yellowstone National Park. J Wild Dis. 1994;30:445-446.

11. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:484-9, 490-516.Â

12. Tessaro SV, Forbes LB. Experimental Brucella abortus infection in wolves. J Wild Dis. 2004;40:60-65.

13. Thompson K. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:172-3.

14. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infection. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis for Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:189-90, 198.