Signalment:

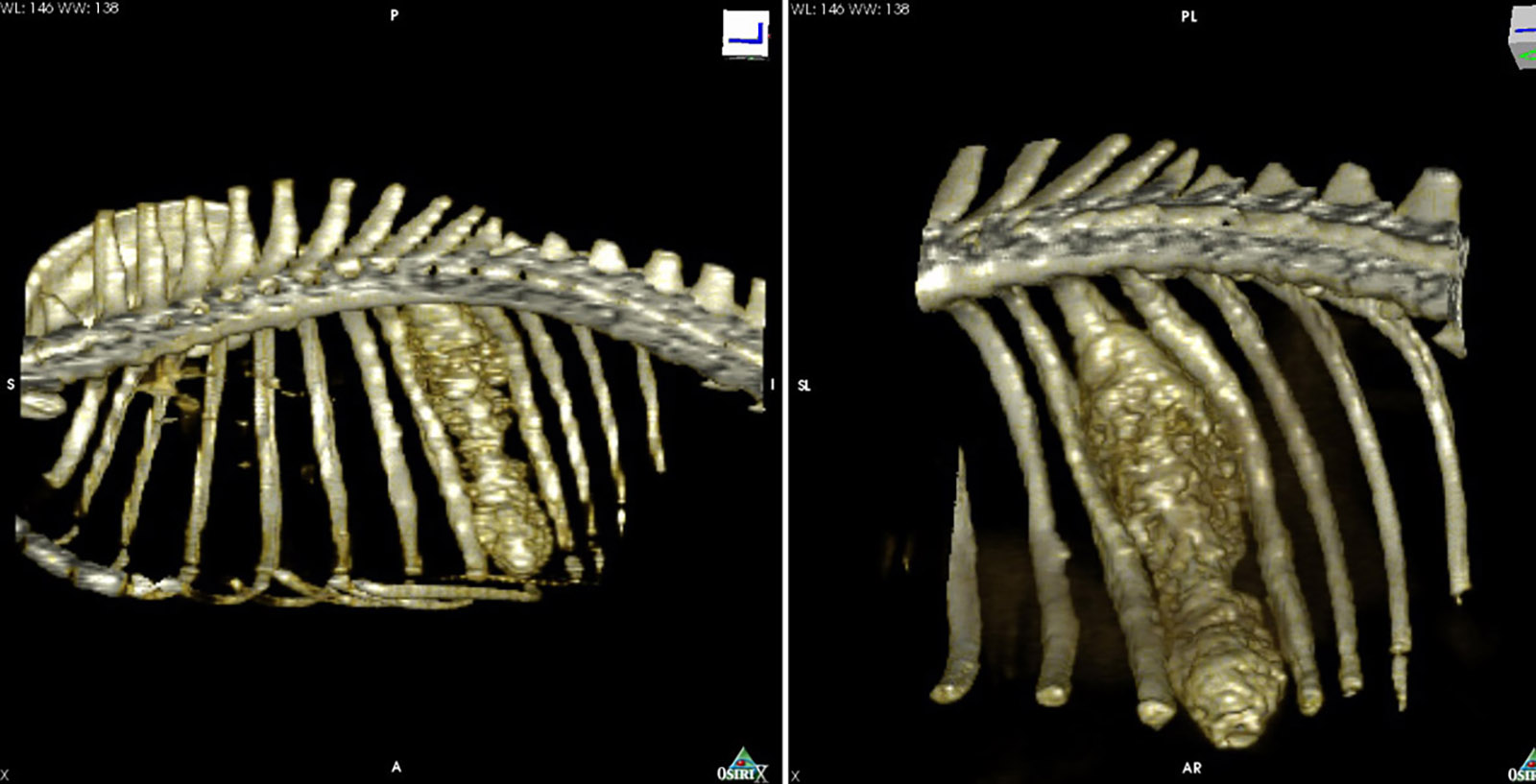

Immunosuppressant therapy was discontinued, but later resumed because of severe thrombocytopenia. A few weeks later, the dog presented with a 15cm diameter swelling on the side of the chest. The swelling appeared to be due to a subcutaneous abscess. The abscess was drained but recurred, at which point surgical debridement was performed. During this procedure, a connection to the rib was identified. The mass was evaluated by CT and resected. Material was submitted for bacterial culture and Corynebacterium spp and Nocardia farcinica were isolated. Eventually, the dog recovered, his CBC normalized, and he is now reportedly in good health.

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

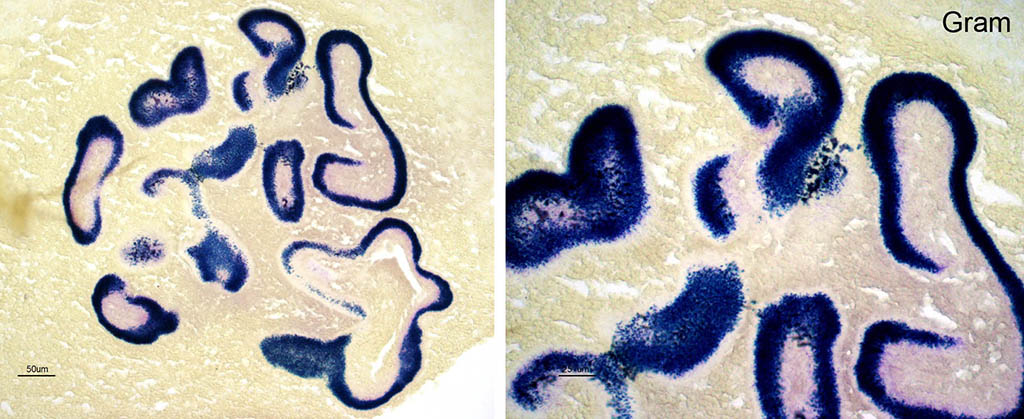

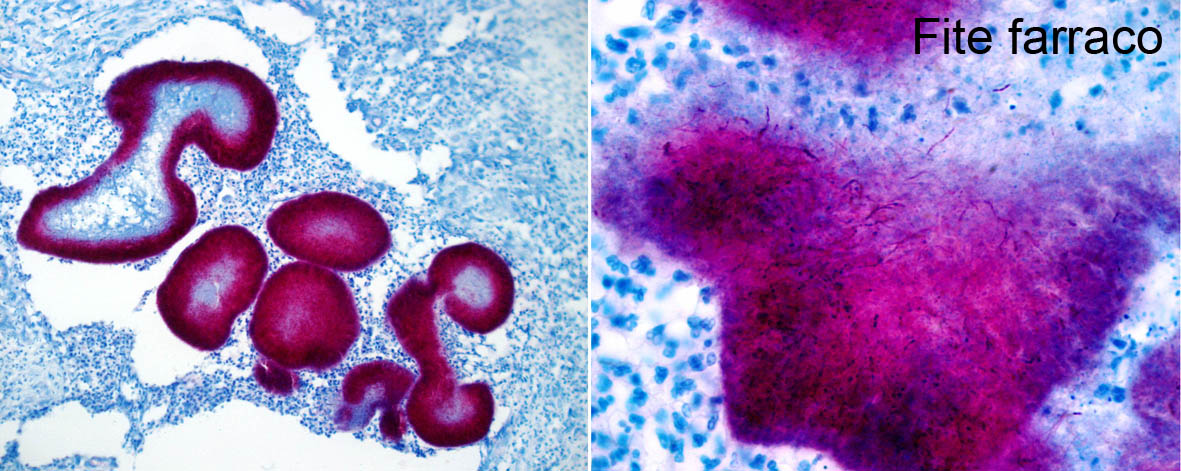

On special stains, the bacteria are gram positive and strongly stain with a modified acid fast stain, Fite-Faraco, and inconsistently with Ziehl Neelsen (ZN). In the modified ZN stain, long filamentous and beaded organisms are easily seen.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Actinobacteria are gram-positive, terrestrial, or aquatic bacteria which constitute one of the dominant bacterial phyla. Most Actinobacteria of medical significance belong to the order Actinomycetales. Due to their filamentous appearance, these organisms were thought to be fungi for many years but were later shown to be higher bacteria.3,7 Actinomyces and Nocardia are the most common Actinomycetes which cause disease. 7 Organisms in the genus Nocardia are aerobic, gram-positive and partially acid fast saprophytes with a worldwide distribution. They commonly occur in soil and decaying organic matter and may cause opportunistic infection. N. asteroides is the species most commonly implicated in disease and has been recovered from lesions in humans, dogs, cats, cattle, goats, horses, pigs, marine mammals and fish.6 Cattle and dogs are the most commonly affected animals, but these infections are sporadic. 3 Infection is not contagious and affected animals do not constitute a public health hazard. 7 Failure to distinguish properly between Nocardia and Actinomyces in earlier reports has caused confusion in the literature regarding nocardiosis in animals. 3

Typically, nocardial infection originates from organisms introduced into skin wounds or aspirated into the respiratory tract, leading to superficial skin lesions, and necrotizing pneumonia, respectively. 3,7 Infections may remain localized at the site of introduction but there is a tendency for the organisms to spread either by direct extension or vascular invasion and hematogenous dissemination. 4,7 There is evidence that strains within the same species vary markedly in their virulence. 4 Cell-mediated immunity and neutrophils appear to be of critical importance in defense against these bacteria. 6,7 In dogs, infections are more common in the young (<1-year-old), which may be due to increased exposure or to reduced resistance. 7

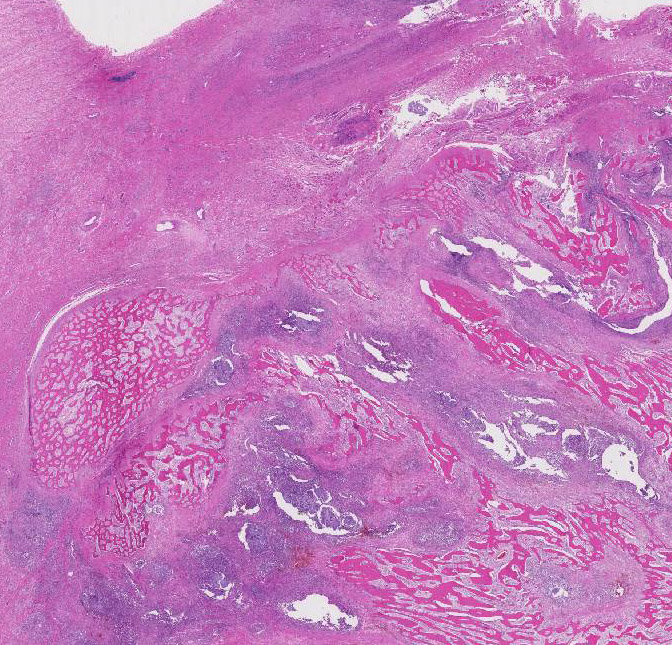

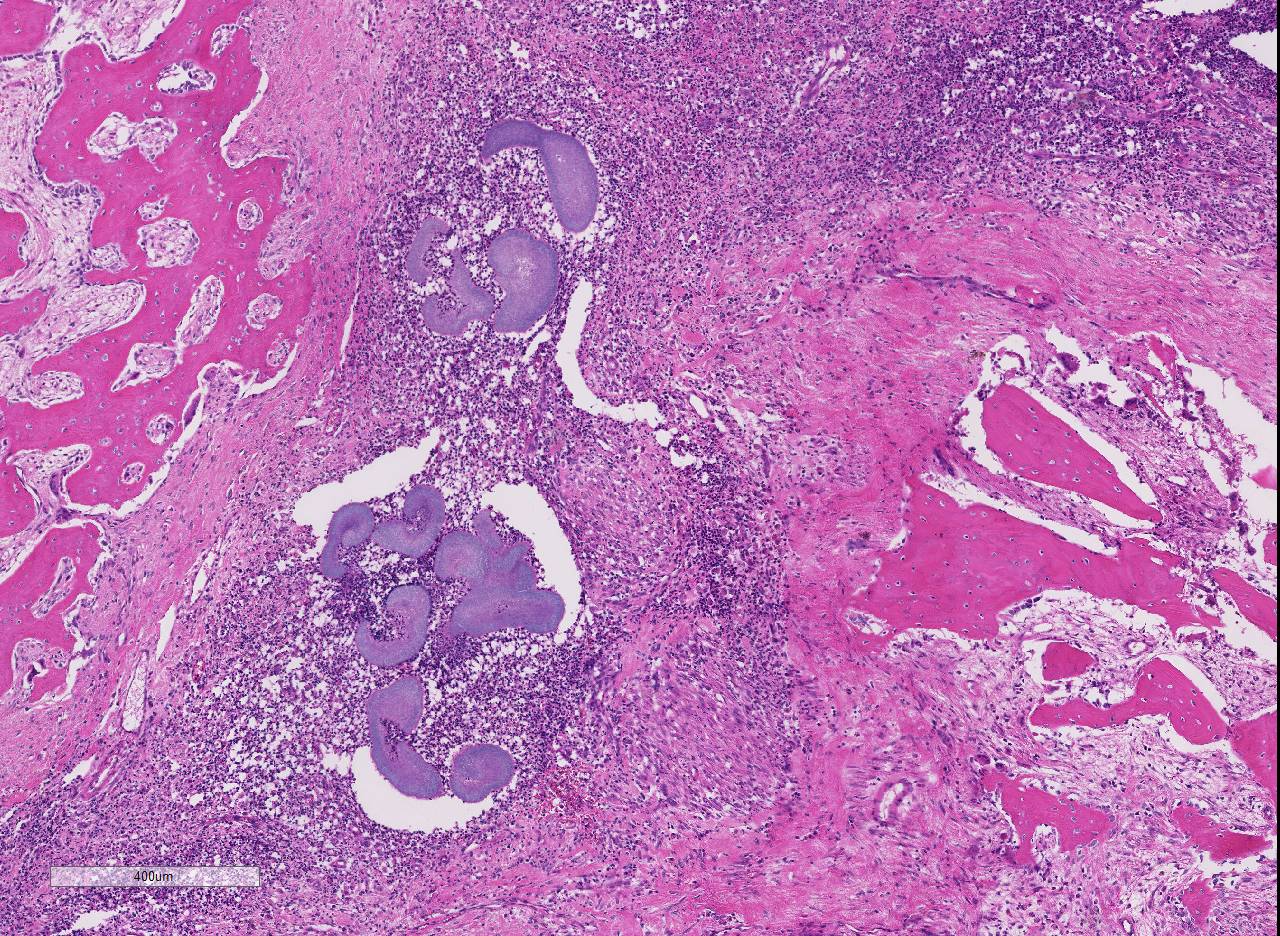

The typical gross cutaneous lesions caused by infection with filamentous bacteria (Actinomyces and Nocardia) consist of abscesses, cellulitis, draining fistulous tracts, and dense fibrous masses. 7 Lesions progress slowly by local extension. The exudate is variable and can contain white, yellow, tan or gray sulfur granules.4,7 Histologically, pyogranulomatous inflammation is commonly seen. 4,7 The sulfur granules consist of masses of organisms, which may be bordered by clubbed corona of brightly eosinophilic Splendore-Hoeppli material.4,7 It has been reported that the shape of this material is characteristic for the agent involved.1 Nocardia spp. have a limited tendency to clump together, thus they typically do not form granules. 4,7 However, in some cases, nocardial lesions are morphologically indistinguishable from those induced by Actinomyces7 , as appears to be the case here. In gram-stained sections, the bacteria are seen as branched and beaded filaments up to 1µm wide. Fragmentation of the filaments produces coccobacillary forms. The beaded appearance is due to alternating gram-positive and gram-negative regions in the filament and is more evident in Nocardia spp. Actinomyces are acid-fast negative with most acid-fast stains. Many, but not all, Nocardia spp. stains strongly with modified Ziehl-Neelsen. Some acid-fast negative Nocardia spp. cannot be differentiated from Actinomyces in sections, and culture is required. 7

The cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules are progressive and may extend to involve underlying bone, as appears to have occurred in this case. The lesion is similar to lumpy jaw in cattle, a classic example of actinomycotic mycetoma. In this condition, traumatic implantation of Actinomyces bovis in the mandibular mucosa progresses to involve the mandibular bone.7 In cattle, N. asteroides can also cause granulomatous mastitis when contaminated drugs for the treatment or prevention of mastitis are introduced through the teat canal. This condition may also occur in outbreaks.2 As noted above, a second relatively common site of infection with filamentous bacteria (Nocardia, Actinomyces and Bacteroides) in dogs and cats is the thoracic cavity, causing pyogranulomatous pleuritis with intrathoracic accumulation of blood-stained pus and reactive mesothelial cells, so-called tomato soup. This is no longer considered pathognomonic of nocardial infection.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Conference participants briefly discussed the pathogenesis of the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. As mentioned above, Splendore-Hoeppli reaction is typically the brightly eosinophilic, radiating, club-shaped, material around bacterial colonies in histologic sections. 2,5,7 This material is composed of antigen-antibody complexes, tissue debris, and fibrin. Although the exact nature of this reaction is unknown, it is thought to be a localized immune response to an antigen-antibody deposition related to fungi, parasites, bacteria or inert materials. The characteristic formation of the Splendore-Hoeppli reaction around infectious agents or biologically inert materials is likely the bodys attempt to contain the injurious agent on the part of the host. However, it also likely prevents phagocytosis and intracellular killing of the agent leading to prolonged damage or infection. 5

Identification of the tissue as costal bone in this section was difficult for all conference participants. As a result, participants discussed effective strategies for differentiating reactive new bone formation from neoplastic bone disease, given the lack of normal tissue architecture. The conference moderator instructed that first one must look for evidence of the parent bone structural elements such as osteons within complex mature lamellar bone to differentiate new bone formation from osseous metaplasia. Next, to differentiate reactive bone from neoplastic bone, one must look at the characteristics and orientation of the osteoblasts. Given that osteoblasts are terminally differentiated products of mesenchymal stem cells, there should be no mitotic activity within this cell population.8 Additionally, in reactive bone formation, osteoblasts form highly organized groups connected by gap junctions allowing the cells to function in a well-regulated manner. In tumor bone, neoplastic mesenchymal cells are haphazardly arranged and produce an osteoid matrix without the regularity and regimentation present in reactive bone osteoblasts.

References:

2. Foster RA. Female Reproductive System. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease . 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1124- 1125.

3. Gyles CL. Nocardia, Actinomyces, and Dermatophilus. In: Carlton L, Thoen CO, ed. Pathogenesis of bacterial infections in Animals. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1993:124-6.

4. Hargis, Ann M, Ginn, Pamela E: The Integument. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1034.

5. Hussein MR. Mucocutaneous Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon. J Cutan Pathol. 2008; 35(11):979-988.

6. MacNeill AL, Steeil JC, Dossin O, Hoien-Dalen PS, Maddox CW. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia abscessus in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol. 2010; 39:381-5.

7. Mauldin E, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier; 2016:637-638.

8. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999; 284:143-7.