Signalment:

Gross Description:

Nutrient status: The frog was severely emaciated.

Integument: The skin on the ventrum, as well as proximally on the hind legs, was diffusely reddened and, mainly on the ventrum, severely eroded. The right forelimb, distal from the elbow, was swollen and had a focal poorly demarcated thickening (1-2 mm) measuring 1 x 0.4 cm dorsally; this involved the subcutis and the underlying musculature which was diffusely discolored yellow (with multifocal yellow crumbly material deposits).

Coelomic cavity: the liver was interspersed with multiple, round, variably sized (0.5-2 mm in diameter) yellowish soft masses that had sometimes a creamy center. All other organs were macroscopically unremarkable.

Histopathologic Description:

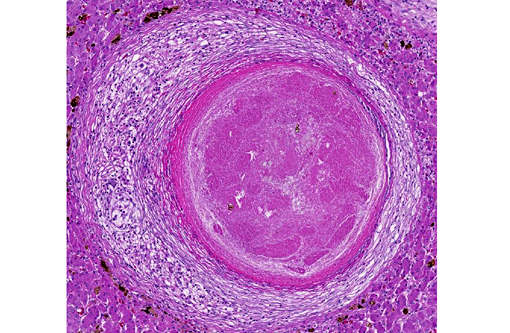

Liver: Randomly distributed there are multiple 1 mm diameter granulomas consisting of central eosinophilic granular material (focal caseous necrosis) surrounded by macrophages and proliferating fibroblasts, forming a thin irregular to thick fibrous wall. Within the granulomas, multinucleated giant cells of the foreign body type (with all nuclei aligned circular at the border of the cells) and of the Langhans type (with randomly arranged nuclei), as well as lymphocytes, are visible. Mainly in the necrotic areas, but also in lesser numbers randomly distributed in the surrounding fibrous wall, there are roundish structures (10-15 μm in +â-+) that are sometimes centrally septated (binary fission) and sometimes grouped in clusters of 2-5. The wall of these structures is brownish-gold with a total thickness of about 1 μm (structures interpreted as fungal sclerotic cells = Medlar bodies). Hyphal structures were not found.

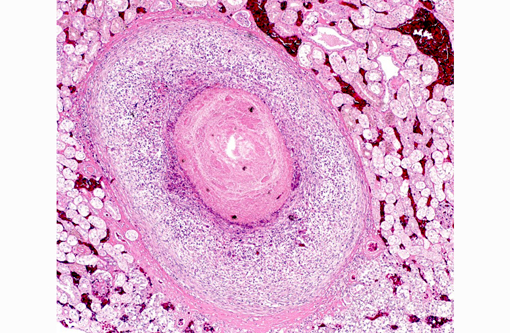

Kidneys (not submitted): Granulomas as described above were found.

Skeletal musculature (not submitted): Multifocally extensive muscular degeneration is present, characterized by loss of cross striations and hypereosinophilia of the cytoplasm. Within the degenerate musculature, small clusters of sclerotic bodies are present embedded within extensive granulomas.

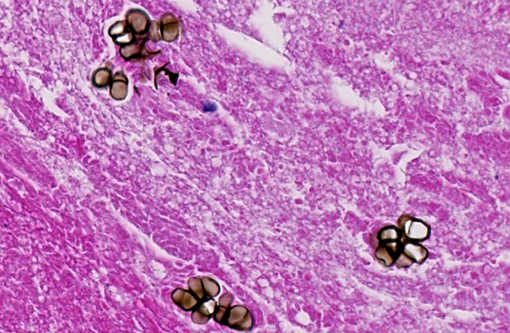

Skin (not submitted): Multifocal extensive and deep ulcerations are observed with embedded pigmented fungi in small amounts.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver: Hepatitis severe, multifocal, (necrotizing and) granulomatous, with presence of fungal pigmented sclerotic bodies and multinucleated giant cells (foreign and Langhans type)

Kidney, coeloma and musculature: Interstitial nephritis, coelomitis and myositis, severe, multifocal, (necrotizing) and granulomatous, with presence of fungal pigmented sclerotic bodies and multinucleated giant cells (foreign and Langhans type)

Skin: Dermatitis, severe, ulcerative and necrotizing, multifocal to confluent, with presence of pigmented fungal structures and secondary severe bacterial colonisation

Musculature: Hyaline muscle fiber degeneration, dystrophic calcification and necrosis, mild to moderate and multifocal

Lab Results:

Ziehl-Neelsen staining: No acid fast bacteria were visible.

PAS staining: The fungal structures were positive but the brownish color obliterated the PAS staining.

A fungal culture was not performed and the PCR of paraffin embedded liver was negative for any fungus.

A parasitologic analysis of the feces was negative.

The bacteriological analysis of the coeloma (swab) demonstrated a mild content of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens, Enterobacter sp., and Acinetobacter sp., all considered most likely as contaminants.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

These ubiquitous fungi are mainly inoculated by trauma. In warm blooded animals (most often humans and rarely other mammals like cats, horses and dogs), the subcutaneous skin is focally affected, growing slowly to warts or verrucous plaques; only seldom and very late in the disease they may disseminate into lymphatics and blood vessels. The most important complications are damage of the lymphatic system and malignant transformation of the epidermis in the affected regions. The pathogenesis of this disease in cold blooded animals differs from the mammalian cases and is usually systemic, involving mainly skin and internal organs; it has been observed mainly in frogs(6) and toads(2,7) but is also present in other amphibians and in reptiles like marine radiate tortoises.(8) Predisposing factors include any kind of stress in animals as, for example, removal from their natural habitat or competition for food with subsequent bite wounds.

Macroscopically, usually ulcerating and non-ulcerating gray to yellow nodules (up to 5mm) are present in the skin (mainly belly, head and legs) and other organs such as liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, body fat, ovaries, brain, spleen, bone marrow. Histologically, these nodules present as granulomas, with central coagulative to caseous necrosis, many multinucleated giant cells, epithelioid cells and dark brown roundish and thick walled fungal structures, also called sclerotic cells, or Medlar bodies, that frequently undergo equatorial septation (replication by binary fission) and lie extracellularly in small clusters or are phagocytosed by giant cells; more seldom, septated hyphae and pseudohyphae are found. In some cases (e.g. the madagascan radiate tortoise(7)), the lesion presents histologically as an abscess with a central core of heterophils and many dark brown sclerotic bodies surrounded by giant cells, lymphocytes and fibroblasts.

The detection of septate sclerotic bodies is pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis. A phaeohyphomycosis, also caused by dematiaceous fungi, can be excluded morphologically because they form broad septate hyphae.

Different therapy protocols exist in humans depending on the fungal agent, location and extent of the lesion. In amphibians and reptiles, the best protocol seems to be amputation. It is only possible if performed during early stages when the infection is limited to the skin; other treatments like antifungal drugs have been reported to be ineffective.(2,6) Because of its zoonotic potential, careful handling of affected animals is advised.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Other dematiaceous fungi include those which cause phaeohyphomycosis. These typically exist in tissue as hyphae rather than the distinct sclerotic bodies of chromoblastomycosis species. Sclerotic bodies are the result of cell division by binary fission, in contrast to most fungal pathogens that replicate through budding.(3)

Important differentials to consider for granulomas in frogs include Mycobacterium marinum and Brucella spp., as both may have some overlap with histopathology. Chromoblastomycosis is a relatively common condition in amphibians and can result in severe systemic disease and frequently death, with the most often targeted organs being the skin, liver, lungs and kidneys. Encephalitis and meningitis has also been reported in these species.(2) Chromoblastomycosis can cause outbreaks in stressed colonies and strict quarantine guidelines must be adhered to due to its transmissibility between animals and humans.(6)

References:

1. Ahmeen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Tropical Doctor. 2010;40:65-67.

2. Bube A, Burkhardt E, Weiss R. Spontaneous Chromoblastomycosis in the Marine Toad (Bufo marinus). Journal of Comparative Pathology1992;106:73-77.

3. Dixon DM, Polak-Wyss A. The medically important dematiaceous fungi and their identification. Mycoses. 1991;34(1-2):1-18.

4. Guedes Salgado Claudio. Fungal x host interactions in chromoblastomycosis, what we have learned from animal models what is yet to be solved. Virulence. 2010;I(I):3-5.

5. McAdam AJ, Milner DA, Sharpe, AH. Infectious diseases. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:388.

6. Miller E, Montali R, Ramsay E. Rideout B. Disseminated Chromoblastomycosis in a colony of ornate-horned frogs (Ceratophirs Ornata). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 1992;23(4): 433-438.

7. Velasquez LF, Restrepo MA. Chromomycosis in the toad (Bufo marinus) and a comparison of the ethiologic agent with fungi causing human chromomycosis. Sabouradia. 1975;13:1-9.

8. Verseput MP. Chromoblastomycosis in a Madagascan Radiate Tortoise, Geochelone Radiata. The Journal of Herpetological Association of Africa. 1990;38(1):14-15.