CASE 3: P17-2052 (4101144-00)

Signalment:

13-year-old, female, Schnauzer, Canis lupus familiaris, dog

History:

The dog presented a diagnosis of intracranial neoplasia (extra-axial lesion in the olfactory and right frontal lobe area). The patient suffered from seizures and due to the worsening of clinical signs the dog was humanely euthanized and submitted for postmortem examination.

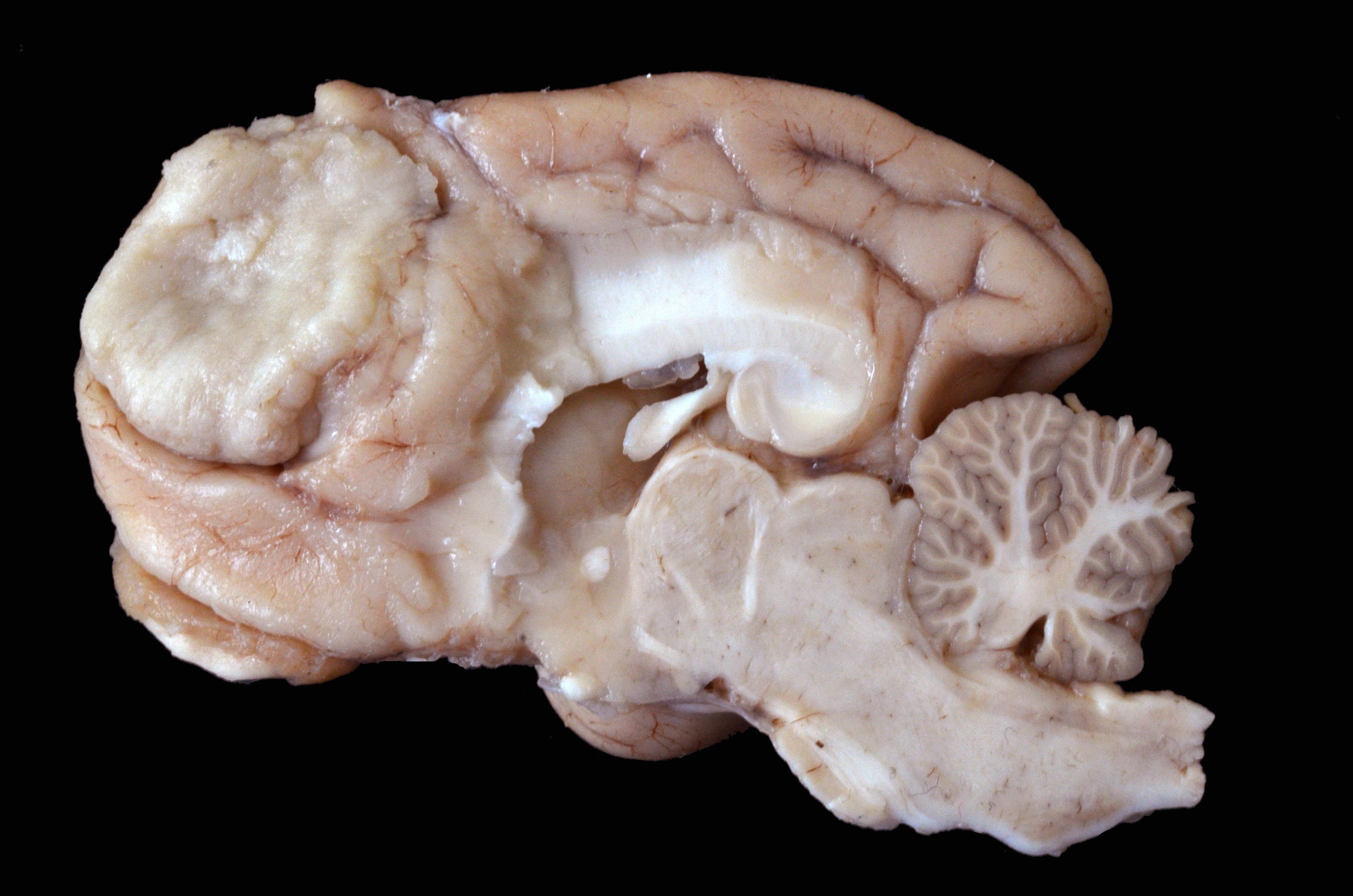

Gross Pathology:

Arising from the right frontal lobe and at the base of the right olfactory bulb, an irregular, firm, white, partially delimited mass with an irregular, surface measuring 1.9 x 1.2 x 2.7 cm was observed. The left frontal lobe was slightly concave by compression of the neoplasm. On cross-sections, the tissue was found occupying and partially replacing both the gray and white matter and its inner surface was well delineated, white to gray, and solid with multiple whitish areas of mineralization.

Other relevant findings were observed in the reproductive tract, where numerous cysts arising from both ovaries were present, as well, as marked endometrial cystic hyperplasia from both uterine horns.

Laboratory results:

None

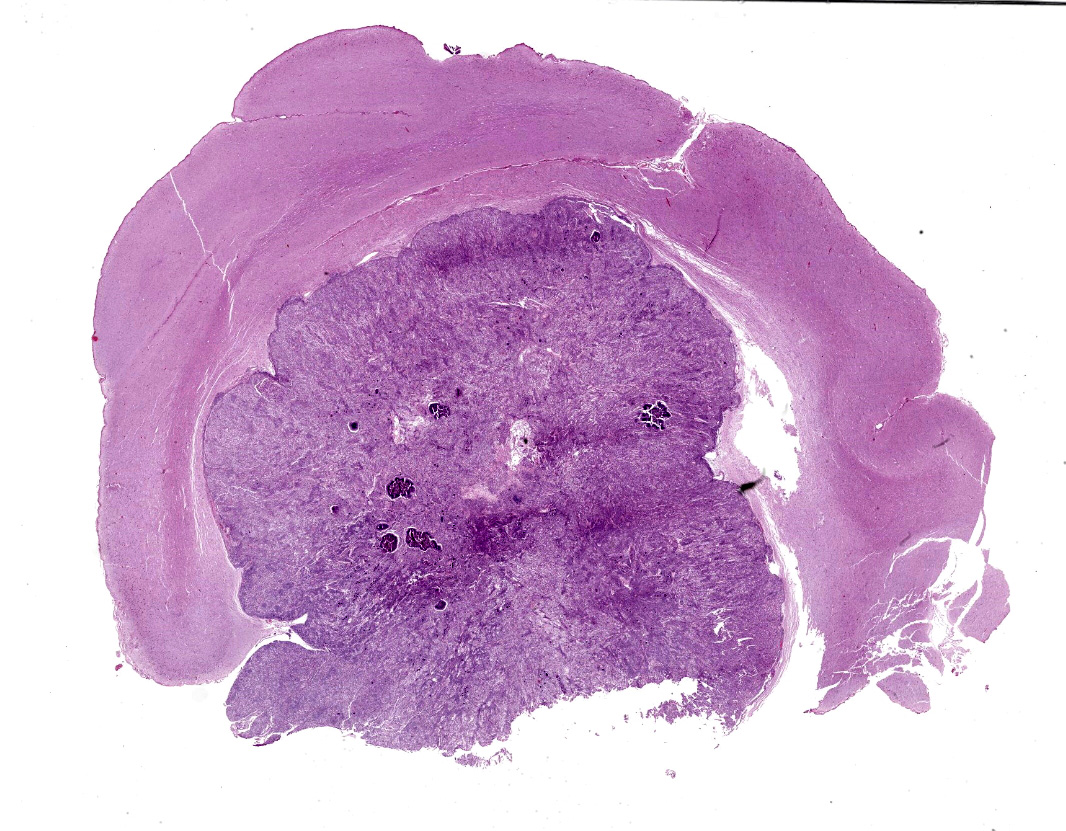

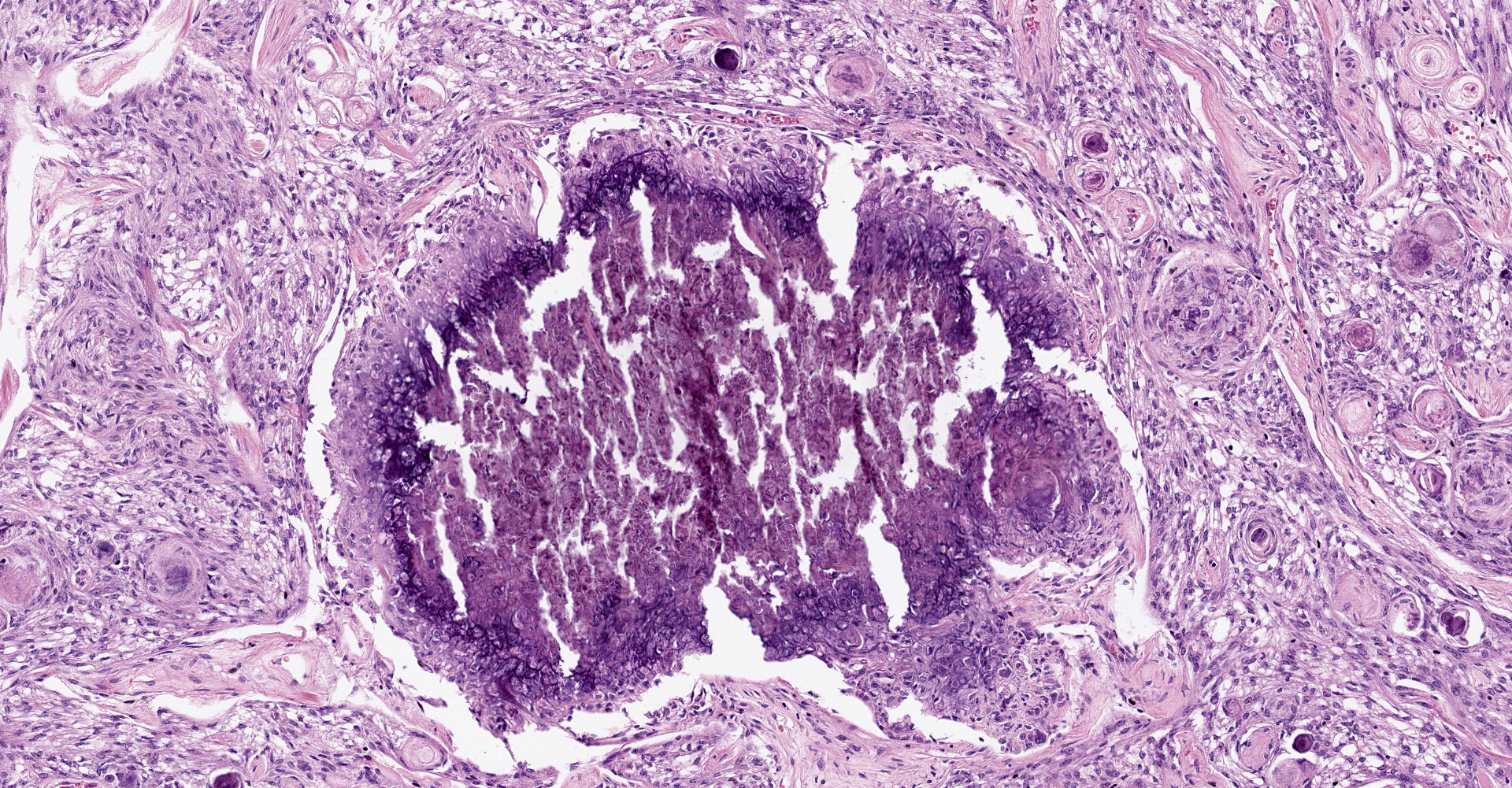

Microscopic description:

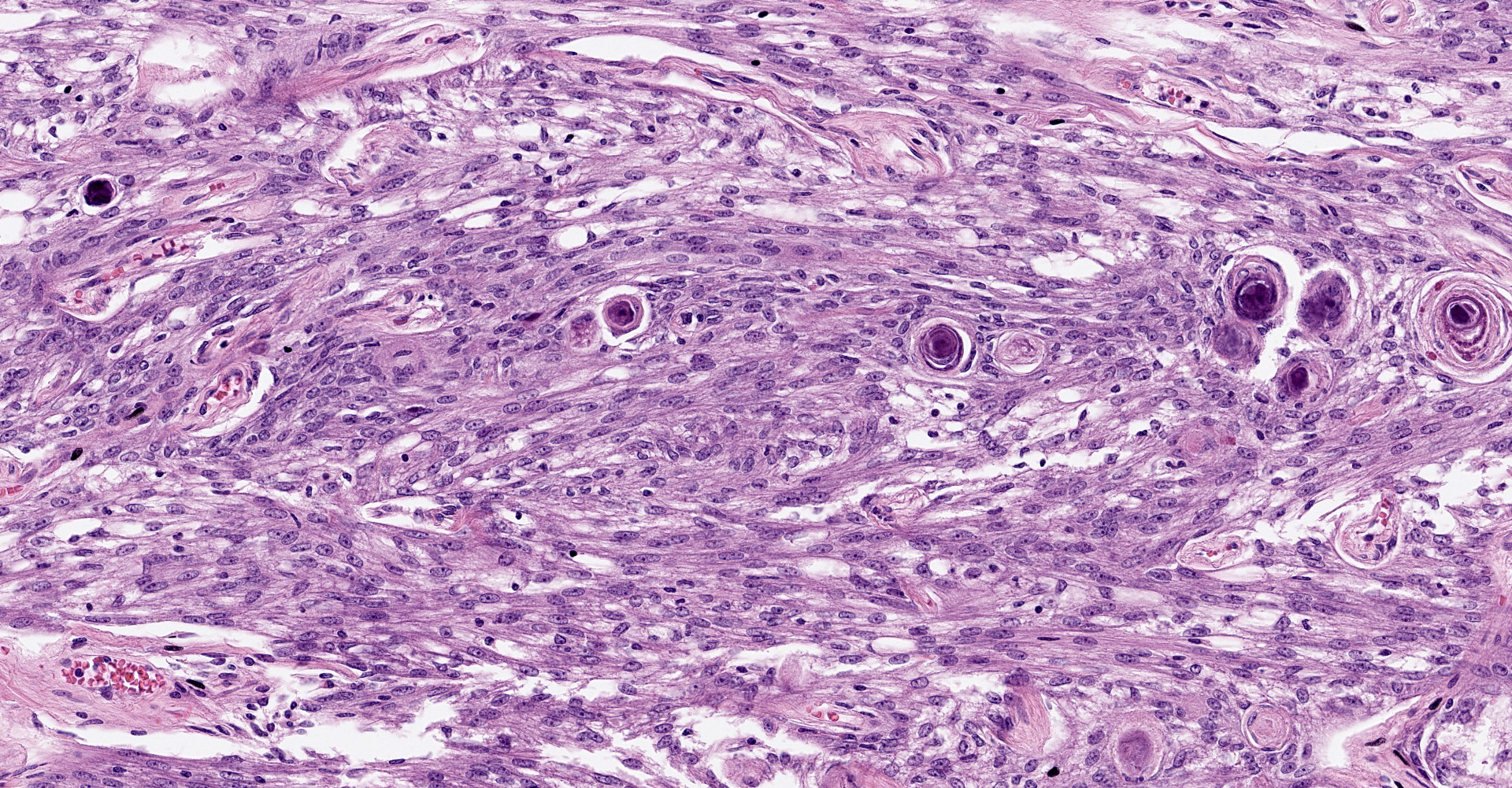

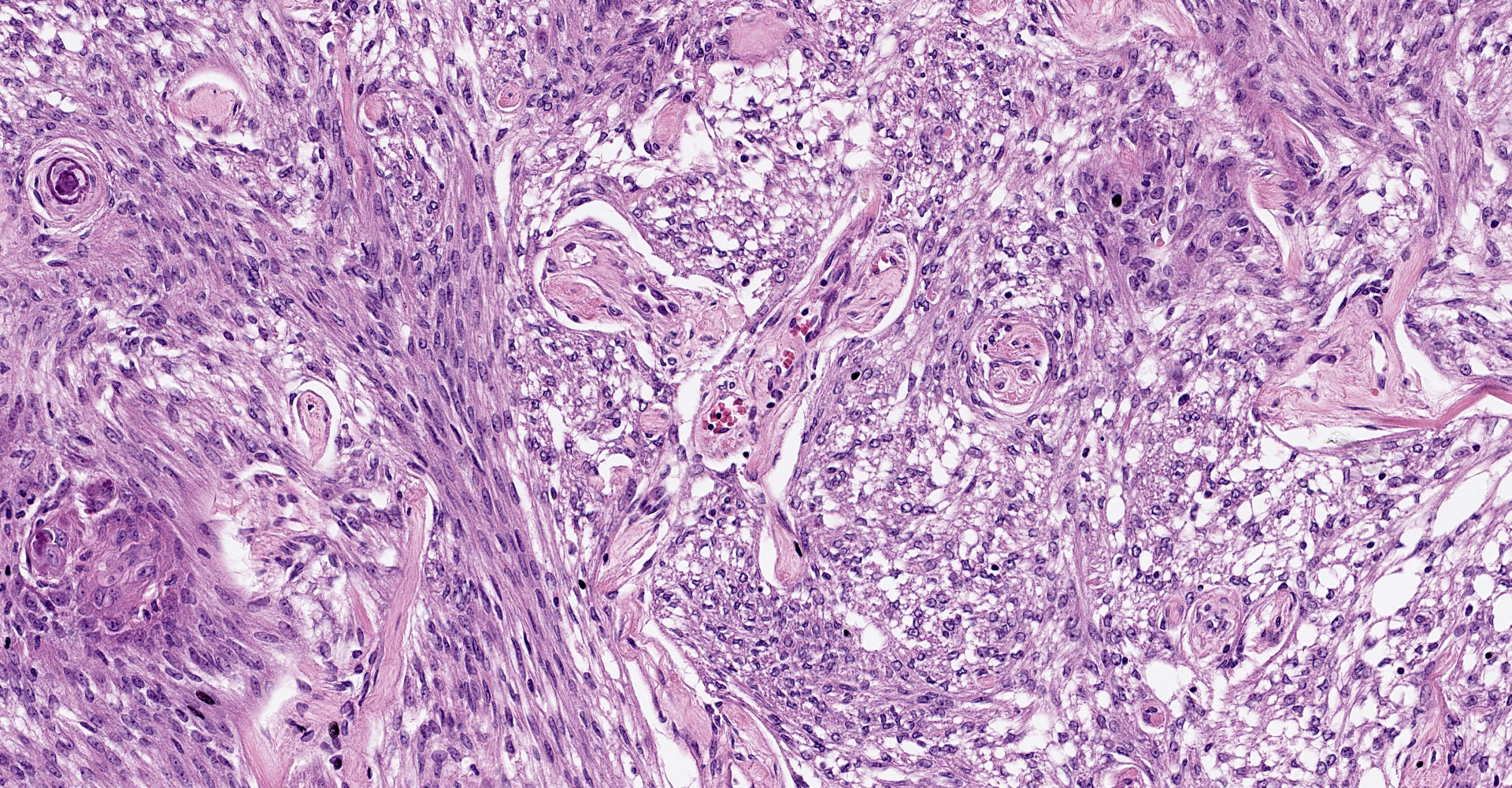

Brain, right frontal lobe: Histologically, there is a proliferation of a well circumscribed, densely cellular neoplasm supported by a thin fibrovascular stroma into nests of closely packed predominantly epithelioid cells or spindle to polygonal cells arranged in loosely interlacing streams and numerous whorls. Neoplastic cells have variably distinct borders with varying amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm, oval to spindle-shaped vesicular nuclei with finely stippled chromatin and predominantly one large distinct nucleolus. Mitoses are rare with less than one mitotic figure per high power field. There is moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. In the core of some whorls, there are multiple basophilic and concentric concretions consistent with areas of mineralization (Psamomma bodies), as well as areas with dystrophic mineralization.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Brain, right frontal lobe: Psammomatous meningioma.

Contributor's comment:

This case had a classic presentation and microscopic features for canine meningioma. In dogs, intracranial meningiomas account for 33% to 49% of all primary brain tumors and are the most common central nervous system (CNS) tumor in this species.1,4,8,9 They occur predominantly beyond middle age, and there is no gender predilection in contrast to their human counterparts, where their presentation in females is more common.4 Most meningiomas are benign. In dogs, they are more common in the brain than in the spinal cord and their development in retrobulbar sites is uncommon. The intracranial meningiomas have favored localizations. They are regularly attached to the dura mater and commonly found in the region of the olfactory bulb and frontal lobes, as observed in this case. Other locations include below the brain stem, the midline attached to the falx cerebri, or the tentorium cerebelli or an intraventricular location associated with choroid plexus.1,4 Their attachment to the dura or leptomeninges may be broad, narrow or total (forming plaque-like masses).4 The main initial clinical sign associated with forebrain meningiomas in dogs is seizures, opposed to cats, where the most common initial clinical signs are lethargy and behavior changes.1 Canine meningiomas show a remarkable biological similarity to their human counterparts, therefore, the grading system in humans (WHO classification system), is commonly used to classify these tumors. The histological subtypes are summarized in table 1. Mixtures of the various forms are common.4 Besides the histologic subtypes, the WHO CNS classification includes a grading scheme that is a malignancy scale based on specific cytological features. In humans, WHO grade is one component of a combination of criteria used to predict a response to therapy and outcome. Other criteria include the age of the patient, neurologic performance status, tumor location, radiological features such as contrast enhancement, extent of surgical resection, proliferation indices, and genetic alterations. For each tumor entity, combinations of these parameters contribute to an overall estimate of prognosis.4,6,7

Canine meningiomas are commonly immunoreactive to vimentin intermediate filaments, cytokeratin and E-cadherin, while being immune-negative to GFAP.

In one study in dogs, incidence of atypical meningiomas was higher compared to their counterparts in humans. Psammomatous meningioma (PMs) had an incidence of 3.5% of the total meningiomas and there were no associations among tumor subtypes or grades or features in magnetic resonance imaging, but microscopically parenchymal edema primarily affecting the white matter was a common feature.8

|

WHO grade |

Histologic subtypes |

Criteria |

|

Grade 1 subtype

"Benign" |

1. Meningothelial 2. Fibrous (fibroblastic) 3. Transitional (mixed) 4. Psammomatous 5. Angiomatous 6. Microcystic 7. Secretory |

Criteria not met for grades 2 or 3. |

|

Grade 2 subtype

"Atypical" |

1. Chordoid 2. Clear cell 3. Atypical |

Mitotic count of at least 4 mitoses/10 HPF Loss of normal architecture (whorls or fascicles) and patternless cell sheets Small cell formation with a high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio Nuclear atypia or macronuclei Hypercellularity Spontaneous necrosis Brain invasion |

|

Grade 3 subtype

"Anaplastic" |

1. Papillary 2. Rhabdoid Anaplastic |

Extreme cellular anaplasia Mitotic count of > 20 mitoses/10 HPF Abnormal mitotic figures Necrosis Brain invasion

|

In humans, intracranial PMs are also a rare subtype of meningioma with low tendency toward growth and recurrence. Intraspinal PMs are more common than intracranial PMs. Most intracranial PMs exhibit highly calcified imaging characteristics, which can be detected by computed tomography. Calcification of intraspinal PM complicates the operative procedure, because of adhesions to the spinal cord, hard tumor consistency and neurovascular

structure encasement.5 These features have not been reported in canine or feline meningiomas. Psammoma bodies (PBs) are concentric lamellated calcified concretions, observed most commonly in several neoplasms like meningioma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, and papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma of ovary and other non-neoplastic lesions. Their formation remains poorly understood, but two major hypotheses have been described. The first one attributes the formation of PBs to degeneration and necrosis of neoplastic cells and subsequent dystrophic calcification. In the second one, PBs formation is considered an active biologic process involving secretion of collagen and membrane bound vesicles in alternate layers by neoplastic cells and the calcification of vesicles, ultimately leading to degeneration/death of tumor cells and growth retardation of the neoplasm that may also serve as a barrier against its spread.3

Contributing Institution:

Departamento de Patología

Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México

Mexico city, Mexico

http://fmvz.unam.mx/fmvz/departamentos/patologia/acerca.html

JPC diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Meningioma, grade 1, microcystic, with psammoma bodies, and chondroid and osseous metaplasia.

JPC comment:

The contributor summarizes canine meningioma well. While most canine meningiomas are grade I (56%), numerous cases are grade II (46%). Approximately 1% are documented as grade III meningiomas. Though varying in histologic patterns, many meningiomas exhibit early loss of tumor suppressor genes NF2, 4.1B, and TSLC1.2

Additional considerations for cases of meningeal disease may include meningeal sarcomatosis. While it usually presents in the lumbar spinal cord and is infiltrative rather than expansile, neoplastic cells are pleomorphic, may extend the length of the spinal cord and be found circumferentially in the arachnoid space. In contrast to a meningioma, these neoplastic cells most often stain negative for cytokeratin.2

In the dog, boxers and golden retrievers have a higher incidence of meningioma, but this tumor has also been reported frequently in cats, and in horses, cattle, pigs, and wildlife to a lesser extent.4 Meningiomas have been reported in Bactrian camels, the short beaked common dolphin, as well as a collared brown lemur.11 Less frequent than the previously described types of meningiomas, granular cell meningiomas have been described in humans and domestic animals. In addition to intracranial meningiomas, extracranial meningiomas have been reported in dogs and humans, with the spinal cord, orbital, paranasal, and cutaneous locations most common. In an investigation of two cases of canine cutaneous meningioma, neoplastic cells were immunopositive for vimentin, but immunonegative for cytokeratin, and neurofilament, and scattered immunopositivity for S-100.9 This may showcase the degree to which neoplastic cell protein expression depends on the microenvironment.

Standardization of neoplasm reporting provides an opportunity for the profession to truly perform more accurate statistical analyses and determine whether our current grading frameworks correlate with clinical outcomes, or whether they require revision. During discussion, the moderator emphasized that saying "less than 1 mitotic figure per?" does not represent an accurate, discrete fact about the neoplasm. If no mitotic figures are observed, state that in the report. There may be slight variation between pathologists, as it is unlikely they will evaluate the exact same 2.37 mm2 area, but variations should be small. The canine meningioma grading scheme is derived from human literature and is outdated.

References:

- Adamo PF, Forrest L, Dubielzig R, Canine and Feline Meningiomas: Diagnosis,Treatment, and Prognosis. Compendium. 2014; 951-956.

2. Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie, MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol I. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2016:396-398, 494.

- Das DK. Psammoma Body: A Product of Dystrophic Calcification or of a Biologically Active Process That Aims at Limiting the Growth and Spread of Tumor? Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2009; 37(7); 534-541.

- Higgins RJ., Bollen AW, Dickinson PJ, Sisó-Llonch S.: Tumors of the Nervous System. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals, ed. Meuten DJ, 5th ed., pp. 864-869. John Wiley & Sons Inc., Iowa, Ames, 2017.

- Lin Z, Zhao M, Ren X, Wang J, Li Z, Chen X , Wang Y, Li X, Wang C, Jiang Z. Clinical Features, Radiologic Findings, and Surgical Outcomes of 65 Intracranial Psammomatous Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2017; 100:395-406.

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol (Berlin) 2007;114:97?109.

- Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Deimling A, Figarella?Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016.

- Sturges BK, Dickinson PJ, Bollen AW, Koblik PD, Kass PH, Kortz GD, Vernau KM, Knipe MF., LeCouteur RA, Higgins RJ. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Histological Classification of Intracranial Meningiomas in 112 Dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:586?595.

- Summers B, Cummings J, deLahunta A: Tumors of the central nervous system, in Summers BA, Cummings JF, de Lahunta A (eds): Veterinary Neuropathology. St Louis, Mosby, 1995, pp 351?401.

- Teixiera LBC, Pinkerton ME, Dubielzig RR. Periocular extracranial cutaneous meningiomas in two dogs. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2014;26(4):575-579.

- Terio KA, McAloose D, St. Leger J, eds. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. 2018; 193, 550, 339.e12.