Signalment:

3.5-week-old, female, Angus calf (

Bos taurus).This calf was born on 2 February 2009 with no known complications. The patient was

lethargic post partum and was administered synthetic colostrum, florfenicol (6 mL), and ceftiofur hydrochloride.

The patient never improved and was transported to the referring veterinarian. The referring veterinarian felt there

was a liver abnormality based upon severe icterus and treated the calf with antimicrobials and vitamin injections.

The patient did not improve and was referred to Oklahoma State University. Physical exam at OSU revealed severe

icterus. Ultrasound revealed hepatomegaly and hyperechoic liver parenchyma, and the gallbladder could not be

located. A congenital biliary anomaly was suspected.

Gross Description:

The patient was in good body condition. The mucous membranes and sclerae were dark yellow.

Internally, the subcutaneous fat, retroperitoneal and pelvic canal fat, intra-abdominal fat, joint fluid, and

cerebrospinal fluid were deep yellow. The liver was enlarged with rounded margins and the capsular surface was

mottled red and yellow. The hepatic parenchyma was diffusely and markedly firm. The gallbladder was not present,

and while the duodenal papilla was present, a discernible bile duct was not observed to communicate with the

papilla. A 2.5 cm diameter focus of gelatinous yellow tissue was present in the region where the gallbladder was

expected to be located.

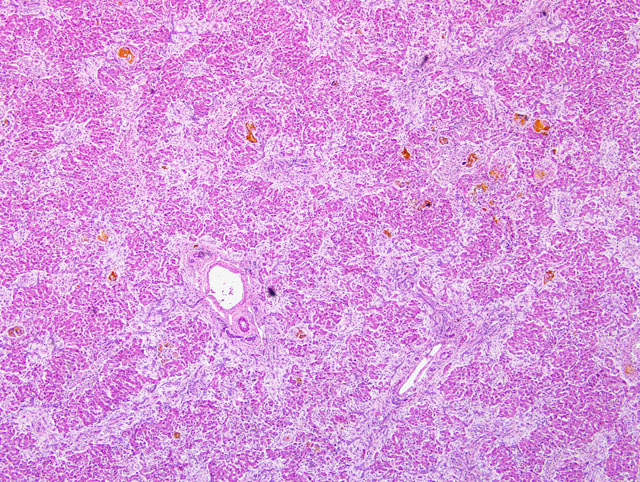

Histopathologic Description:

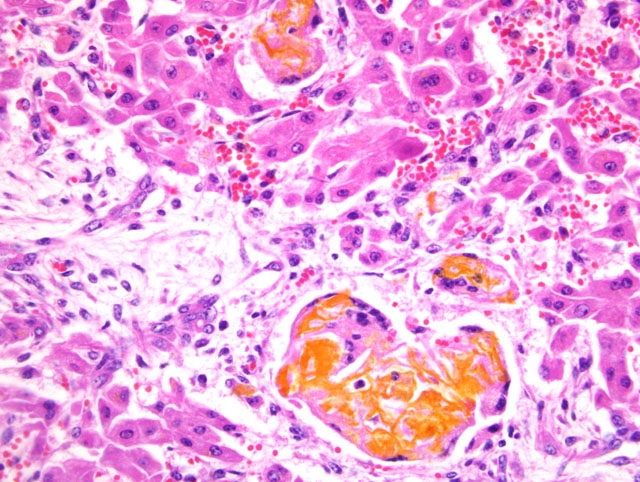

The normal lobular architecture of the liver is disrupted by tracts of proliferative,

branching and anastomosing, hyperplastic bile ducts surrounded by moderate to marked amounts of fibrous

connective tissue (confirmed with trichrome stain). These tracts extend between adjacent portal triads and often to

the central veins. Hepatocellular cords are separated into small islands by the bands of fibrous connective tissue and

hyperplastic bile ducts. Golden bile pigment (confirmed with Halls special stain) forms multiple lakes that often

replace hepatocytes and are scattered throughout the hepatic parenchyma. Bile pigment is also often present within

multinucleated giant cells.

The small tissue specimen from the region of the gallbladder is composed largely of fibrous connective tissue that

contains few bile duct profiles nested together peripheral to a larger, central, epithelial-lined ductal or aplastic

bladder-like structure. Scattered at the borders of the tissue are small amounts of smooth muscle.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Liver: Severe intrahepatic bile duct hyperplasia and periportal fibrosis

with marked hepatocellular loss and severe, multifocal cholestasis with bile lake formation.

2. Gallbladder and duct: Gallbladder aplasia with extrahepatic biliary atresia.

Condition:

Biliary atresia

Contributor Comment:

Congenital biliary atresia is discontinuity or obstruction of the biliary tree (extrahepatic

or intrahepatic) that results in severe icterus and liver damage in young patients. The disease is rare, though welldescribed

in people, and the defect occurs alone or in combination with other congenital defects. The condition has

been reported in several veterinary species including foals, lambs, calves, cats and dogs.(1,4-6) Whether or not

gallbladder agenesis/aplasia is included or encompassed within the diagnosis of biliary atresia is variable between

reports. Since it is well documented that biliary atresia can be intrahepatic or extrahepatic (or both) and occurs with

or without gallbladder lesions, it is probably best that the two conditions remain separate morphological diagnoses.

In reports from people and animals, livers have been described as macroscopically large or shrunken. The

histological lesion in the liver is more similar across species and characterized predominantly by portal and bridging

fibrosis with either an absence of bile ducts (intrahepatic atresia) or marked proliferation of bile ducts (in

extrahepatic atresia). There is marked cholestasis. The hepatic histological lesion is similar to that of calves with

congenital hepatic fibrosis syndrome; therefore, evaluation/verification of the gallbladder and bile duct is important

in the delineation of these syndromes.

The etiology of biliary atresia in man and animals is debatable. Most follow two pathways of either congenital

defects in morphogenesis or post-formation destruction (whether prenatal or postnatal), usually blamed on infection/

inflammation.(1,2) Defects in morphogenesis are suspected to be either inherited or secondary to gestational toxin

exposure.(2,5) Post-formation inflammatory destruction of the biliary tree has been blamed on viral infections and

immune-mediated destruction in people and severe biliary ascarid invasion with subsequent inflammation and

blockage in the dog.(2,6)

JPC Diagnosis:

Liver: Bridging fibrosis, diffuse, marked, with biliary hyperplasia, hepatocellular loss,

canalicular cholestasis and bile granulomas.

Conference Comment:

We are grateful to the contributor for furnishing this very instructive case. As is customary

at the AFIP, conference participants were denied prior access to the submitted history, necropsy findings, and gross

image; while creating a rather artificial handicap, the method provides for a rich educational opportunity, primarily

by reducing bias and thus stimulating discussion. Uniformly, conference participants strongly suspected a toxic

etiology in this case based upon the diffuse distribution of the lesions. More specifically, participants interpreted the

prominent bridging fibrosis and loss of hepatocytes as consistent with chronic hepatointoxication. The striking

lesions attributable to cholestasis (i.e. bile lakes and granulomas; ectatic, albeit usually empty, bile canaliculi; and

biliary hyperplasia) led many participants to precisely implicate toxins that target the biliary epithelium, such as the

mycotoxin sporidesmin and the plant

Tribulus terrestris, which causes a toxicosis known as geeldikkop in sheep.

Careful examination of the specimen, however, reveals compelling evidence against both of these toxins, such as the

paucity of inflammation, besides that which is associated with bile lakes (bile granulomas). Sporidesmin, produced

by the fungus

Pithomyces chartarum, concentrates in the bile, directly irritating the connective tissues of the portal

tracts and bile ducts, and at high concentrations, causes biliary epithelial necrosis; the result is acute cholangitis or

cholangiohepatitis. Although generally mild, the inflammation in sporidesmin toxicosis is typically more severe

than that present in this case. Moreover, sporidesmin causes extensive necrosis of bile duct epithelium with

sloughing of necrotic debris into the lumen, features lacking in this case. Saponins of the plant

Tribulus terrestris

are likely responsible for geeldikkop (yellow bighead) in sheep, which is distinguished grossly by the presence of

white, semifluid, crystalline material in the cystic and larger intrahepatic bile ducts. Histologically, hepatocyte

vacuolation and Kupffer cell hyperplasia are characteristic of the acute toxicosis, whereas crystalline material within

the bile ducts and hepatocytes is more obvious in chronic intoxication; none of these is a feature of the present case.

(7)

This exercise underscores the value of resisting the temptation to commit to just one category of etiology (e.g., toxic,

infectious, congenital, degenerative, neoplastic, etc.) without first giving due deliberation to the other potential

categories that may produce a similar constellation of microscopic lesions. The clinical history and gross findings

substantially amplify the index of suspicion for a congenital abnormality in this case. That said, the cause of biliary

atresia remains enigmatic, and indeed the condition may represent a common phenotypic result of a number of

different causes, including inherited defects and/or in utero intoxication targeting the biliary epithelium. In support

of the latter, the pyrrolizidine alkaloid-containing plant,

Senecio sp., has been implicated as the cause of

in utero

liver damage in calves whose dams ingested the plant during pregnancy.(3) Intriguingly, a 1988 outbreak of

congenital biliary atresia in lambs and calves in New South Wales, Australia, occurred at the same site as a similar

outbreak in lambs in 1964. Epidemiologic evidence, including the simultaneous occurrence in both calves and

lambs in the second outbreak, argued against an inherited defect, and signified that the lesion may have stemmed

from a toxic or infectious insult to the developing fetuses that produced choledysgenesis and biliary atresia

in utero;

although several suspect weeds were investigated, a specific etiology was not confirmed.(5)

This case was reviewed in consultation with the AFIP Department of Hepatic Pathology, which noted remarkable

histomorphological similarities with cases of biliary atresia in human neonates. Although only rarely reported in

other species, biliary atresia in humans is the most common cause of neonatal cholestasis and the most common

indication for pediatric liver transplantation; yet, its cause remains obscure, with evidence put forth in support of

five possible mechanisms: 1) viral infection, 2) environmental toxin exposure, 3) immunologic/inflammatory

dysregulation, 4) defective biliary tract morphogenesis, and 5) defective fetal/prenatal circulation.(2)

References:

1. Bastianello SS, Nesbit JW: The pathology of a case of biliary atresia in a foal. J S Afr Vet Assoc

58:89-92, 1987

2. Bezerra JA: Potential etiologies of biliary atresia. Pediatr Transplantation

9:646-651, 2005

3. Fowler ME: Pyrrolizidine alkaloid poisoning in calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc

152:1131-1137, 1968

4. Hampson ECGM, Filippich LJ, Kelly WR, Evans K: Congenital biliary atresia in a cat: a case report. J Small

Anim Pract

28:39-48, 1987

5. Harper P, Plant JW, Unger DB: Congential biliary atresia and jaundice in lambs and calves. Aust Vet J

67:18-22,

1990

6. Schulze C, Rothuizen J, van Sluijs FJ, Hazewinkel HA, van den Ingh TSGAM: Extrahepatic biliary atresia in a

border collie. J Small Anim Pract

41:27-30, 2000

7. Stalker MJ, Hayes MA: Liver and biliary system: toxic hepatic disease.Â

In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers

Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 372-378. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia,

PA, 2007