CASE 4: H15-877 (4073704-00)

Signalment:

5-day old pig, breed and gender unspecified, Sus scrofa, porcine

History:

Commercial, fully integrated pig farm with a neonatal diarrhoea problem ongoing for 2-3 weeks. 25% of (mainly gilt) litters affected. 100% morbidity within litters and approximately 20% mortality. Five very recently dead piglets submitted for necropsy.

Gross Pathology:

Carcasses well preserved with adequate body fat reserves. Stomachs filled with milk. Fluid yellow intestinal and colonic contents. Mild mesocolonic oedema. No gross changes noted in intestinal, cecal or colonic mucosa. Other body systems unremarkable.

Laboratory results:

ELISA for Clostridium difficile toxins A and B positive on colonic contents. No pathogenic bacteria isolated from intestinal contents. ELISA for Clostridium perfringens toxins negative. PCR for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, porcine delta corona virus, transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus negative. Polyacrylimide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) for rotaviruses negative.

Microscopic description:

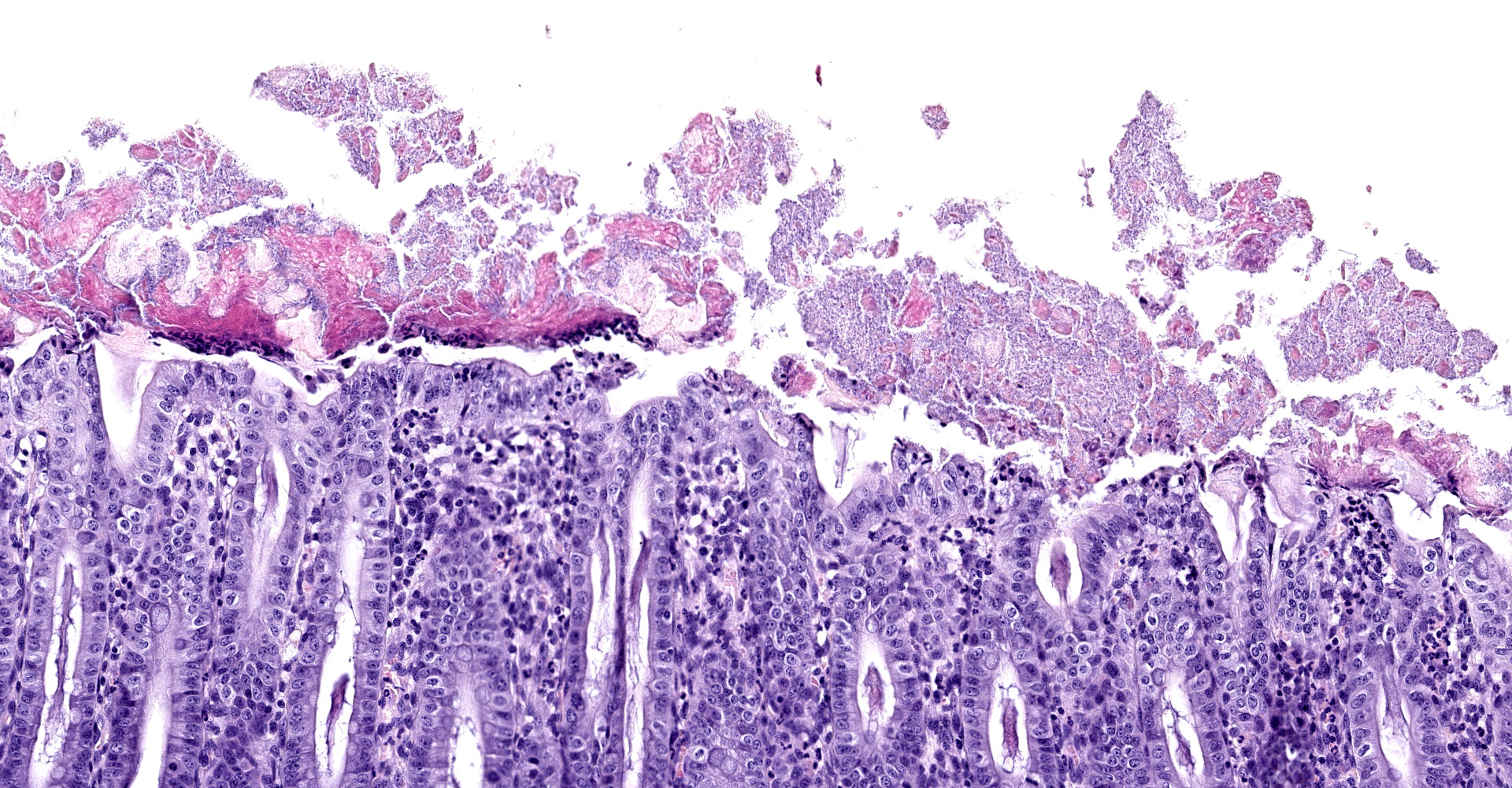

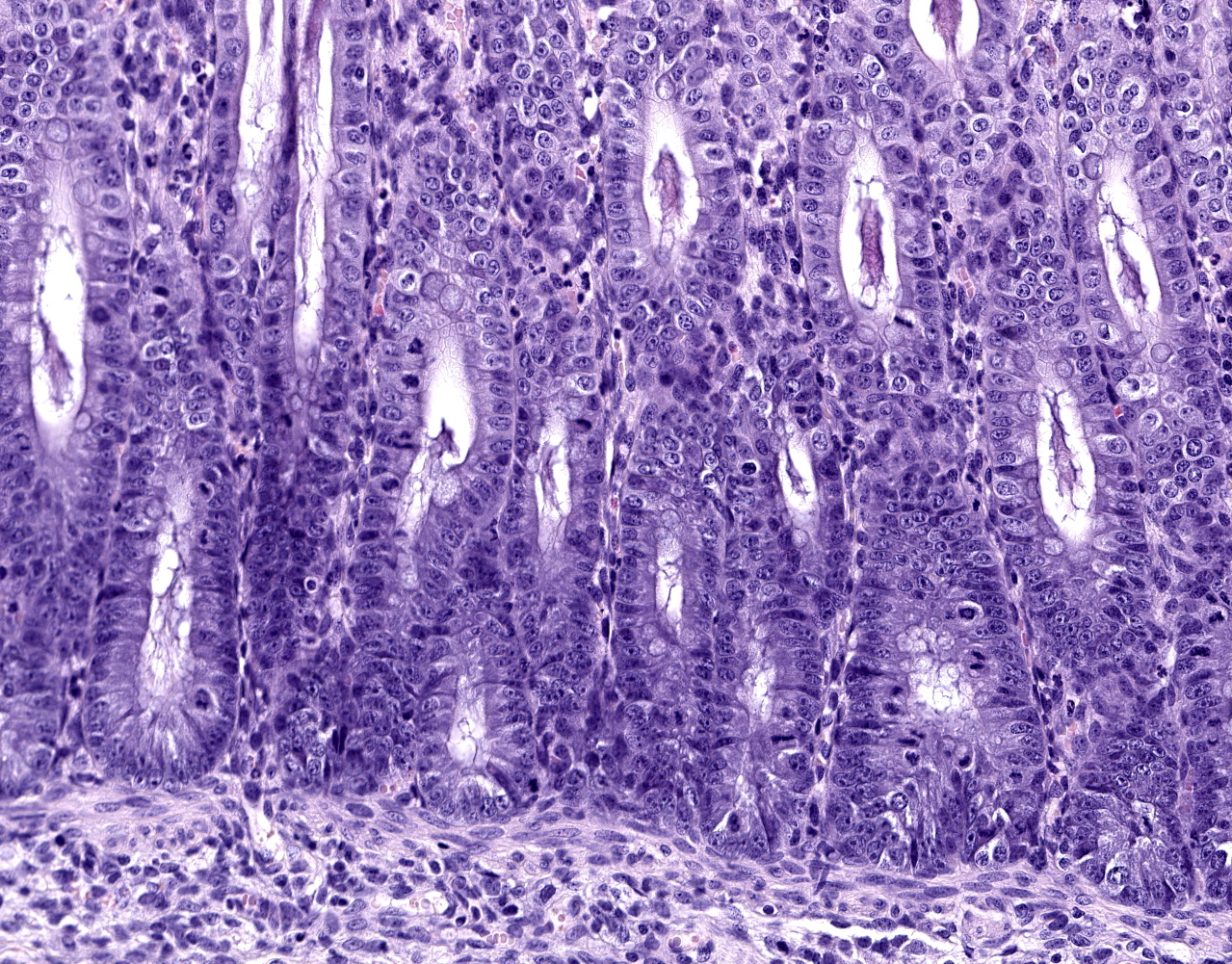

Caecum and spiral colon: There is some variation in sections. Multifocally there is superficial erosion/ulceration of epithelium with exudation of neutrophils into the subjacent lamina propria and spilling of neutrophils, and in some sections fibrin, into the lumen ('volcano' lesions). Within lumens are multifocal mixed aggregates of bacteria (long bacilli and cocci). Mild, multifocal to coalescing oedema of superficial lamina propria and mild mesocolonic oedema.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Cecum and colon: Typhlocolitis, fibrinopurulent, erosive, necrotizing, acute, superficial, multifocal, moderate.

Contributor's comment:

Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive spore-forming anaerobic enteropathogen of humans and animals.4 Porcine neonatal Clostridium difficile-associated disease (CDAD) typically affects animals 1-7 days of age and has recently emerged as a major cause of diarrhoea in young piglets in North America and Europe. The clinical history typically includes early-onset diarrhoea, rarely respiratory distress, and sudden death. There may be oedema of the mesocolon and the colon may have pasty-to-watery yellowish content.5 Hydrothorax, ascites and scrotal oedema have also been described.8 Mucosal lesions of pigs are limited to the cecum and colon. These are typically mild, but vary from grossly inapparent, multifocal necrosis of surface epithelial cells to transmural necrosis. Pigs with spontaneous disease have microerosion/ulceration with effusion of fibrin and neutrophils into the lumen, so-called 'volcano ulcers'. Suppuration of the colonic lamina propria is the common microscopic lesion, with colonic serosal and mesenteric oedema with accompanying infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells and neutrophils. Segmental erosion of colonic mucosal epithelium is common, and volcano lesions may be evident.5

CDAD occurs opportunistically when the niche usually occupied by endogenous intestinal flora is disrupted, either by a change in diet or by antimicrobial treatment.6 C. difficile produces two major toxins. Toxin A (TcdA) and Toxin B (TcdB) that act synergistically to cause apoptosis of mucosal epithelial cells and disruption of actin filaments that results in loss of cell-to-cell contact and increased paracellular permeability of mucosae. Toxins A and B have other effects, notably initiation of an inflammatory cascade that can result in increased damage to host tissues and exudation of fluid.4 The requirements for development of CDAD are disruption of normal intestinal or colonic flora, presence of the organism in the environment and the production of toxins.6

The standard diagnosis for porcine CDAD is detection of TcdA and TcdB in faeces or colonic content, generally using commercially available enzyme immunoassays. Cultivation of C. difficile is difficult and because it can be found in healthy pigs, its isolation may have little diagnostic relevance.5 CDAD develops spontaneously in a variety of other species including horses, hares, non-human primates, domestic dogs, domestic cats, ostriches, and black-tailed prairie dogs.4 C. difficile is also one of the most important nosocomial pathogens of humans, primarily associated with intestinal dysbiosis following antibiosis. In recent years the epidemiology of the disease in human patients is changing with more community acquired infections and the emergence of strains in humans that are common in domestic animals. The pathogen is thus now being considered a potential zoonosis.6

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Sciences Centre

School of Veterinary Medicine

University College Dublin

Belfield, Dublin 2, Ireland

JPC diagnosis:

Colon: Colitis, erosive and neutrophilic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate, with edema and crypt hyperplasia.

JPC comment:

This pathogen, now named Clostridioides difficile, remains a significant pathogen in human and veterinary populations. In 2011, there were approximately 453,000 human C. difficile infections in the United States. While the distribution of different virulent ribotypes has changed with the use of differing antibiotic classes in different parts of the world, incidence of ribotype 78 C. difficile infection has been increasing since 2005. This virulent strain primarily affects pigs and calves, but also infects humans, and there has been an association between pig farms and human infection documented in the Netherlands.2

Contamination of food destined for human consumption remains a problem around the world. A study in Japan tested commercially available foods at supermarkets and found C. difficile contamination in 3.3% of free vegetables, 6.7% of chicken meat, 3.6% of chicken liver, 0.5% of pork meat, and 1.6% of beef meat sampled. Additionally, the presence of Toxin A, Toxin B, and binary toxin (CDT) was detected in samples, as well as some isolates being resistant to common antibiotics. The rates of contamination in this study were comparatively low compared to the United States and should provide ample motivation for thorough food inspections.7

While the most common method of contracting disease is an alteration of the gut flora, usually through antibiotic use. However, exposure and transmission has not been well investigated. A great number of spores are likely in most contaminated environments, but they may not all be perpetuated by pigs. A survey of pigs and rodents collected across two farms revealed the mice and rats were capable of carrying C. difficile, with a prevalence between 25-50%. Further research is necessary to determine the extent of rodent transmission or persistence of C. difficile infections in pigs.1

While there is no commercially available vaccine against this agent, an alternative treatment has been explored. Following work performed in laboratory rodents, the non-toxigenic strain of C. difficile Z31 was administered to 1-day old piglets, with subsequent fecal analysis 24 hours later. Administration of the Z31 strain statistically significantly reduced C. difficile infection, as compared to controls. In the animals that did develop disease, the intensity of diarrhea was reduced. This may represent a valid preventive for the pig industry.3

References:

- de Oliviera CA, Gabardo MdP, Guedes RMC, et al. Rodents are carriers of Clostridioides difficile strains similar to those isolated from piglets. Anaerobe. 2018;51:61-63.

- Guh AY, Kutty PK. Clostridioides difficile infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):ITC49-ITC64.

- Junior CAO, Silva ROS, Lage AP, et al. Non-toxigenic strain of Clostridioides difficile Z31 reduces the occurrence of C. difficile infection (CDI) in one-day-old piglets on a commercial pig farm. Veterinary Microbiology. 2019;231:1-6.

- Keel MK, Songer JG. The comparative pathology of Clostridium difficile?associated disease. Vet Pathol. 43:225?240, 2006.

- Songer JG, Uzal FA. Clostridial enteric infections in pigs. J Vet Diagn Invest.17: 528, 2005.

- Squire MM, Riley TV. Clostridium difficile infection in humans and piglets: a 'one health' opportunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 365:299-314, 2012.

- Usui M, Maruko A, Harada M, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Clostridioides difficile isolates froim retail food products (vegetables and meats) in Japan. Anaerobe. 2020;61:102132.

- Waters EH, Orr JP, Clark EG, Schaufele CM. Typhlocolitis caused by Clostridium difficile in suckling piglets. J Vet Diagn Invest. 10:104?108, 1998.