Signalment:

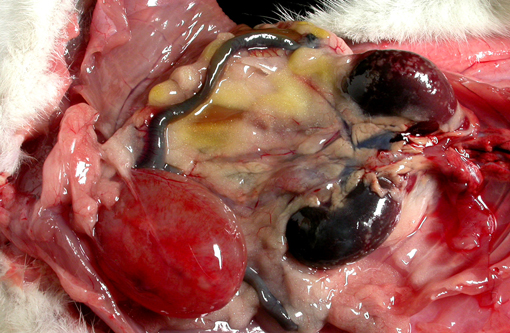

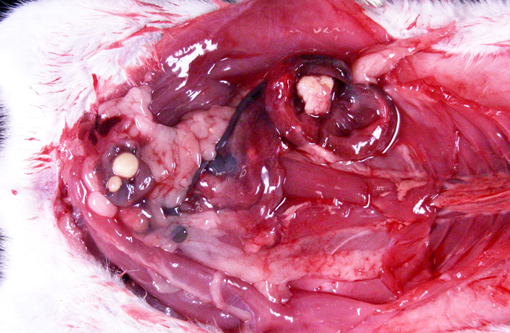

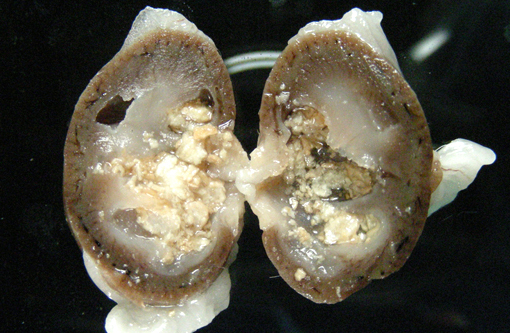

Gross Description:

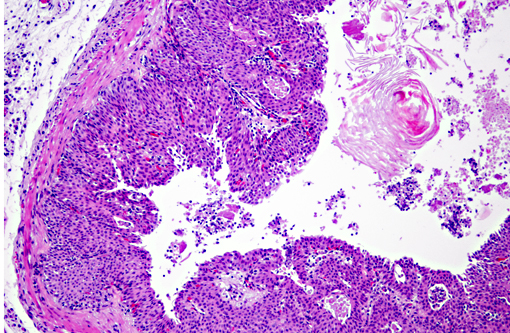

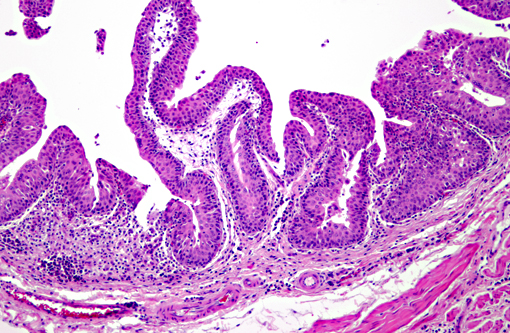

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Vitamin A regulates epithelial cell growth and differentiation, enables production of visual pigment, is necessary for normal function of the immune system, and influences skeletal development(8). When rats are fed diets that contain no vitamin A, the most commonly reported clinical signs of deficiency are weight loss, corneal keratinization and ulceration, respiratory or skin disease, and salivary gland enlargement.(1) An 80% mortality rate due to inanition or bacterial infection of the skin or respiratory tract is expected after 15 weeks.(1) In the present case, the rats received some vitamin A, albeit in inadequate quantities. The restriction of the lesions to the transitional epithelium in these rats suggests that the transitional epithelium is the most susceptible to squamous metaplasia due to moderate vitamin deficiency(6). The squamous metaplasia of the transitional epithelium then predisposed to the development of ascending bacterial infections and urolith and nephrolith formation.

While squamous metaplasia of the transitional epithelium lining the renal pelvis can occur secondary to bacterial infection, the metaplasia visible within the present case was considered an excessive reaction to an ascending bacterial pyelonephritis.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Vitamin A deficiency leads to impaired epithelial differentiation through an unknown mechanism, and leads to reduction in mucus-secreting cells, squamous metaplasia of the respiratory and genitourinary epithelium, and hyperkeratosis(4). Hypovitaminosis A also leads to retarded osteoclastic resorption of endosteal bone, and lesions are varied depending on species affected, stage of growth, and severity of the deficiency(7). Vitamin A deficiency also leads to the arrest of spermatogenesis at the spermatid phase in all species, especially in cattle, rats, and chickens, and causes abnormal estrous cycles, congenital anomalies, and fetal resorption. Hypovitaminosis A affects immune function, as vitamin A is thought to stimulate T-cells directly through 14-hydroxyretinol. During infection, synthesis of the negative acute phase protein, retinol-binding protein, is down-regulated, decreasing availability of vitamin A(4).

In dogs, vitamin A deficiency results in hyperkeratosis of sebaceous gland ducts; vitamin A-responsive dermatosis in cocker spaniels is characterized by marked follicular keratosis of the chest and abdomen(2). In male calves, vitamin A deficiency results in stenosis of the optic foramen and atrophy of the optic nerve, leading to blindness. Squamous metaplasia of the parotid gland is a pathognomonic lesion of hypovitaminosis A in cattle(9). In guinea pigs and rats, vitamin A deficiency results in inadequate differentiation and organization of odontoblasts, leading to irregular dentin formation and enamel hypoplasia(5).

References:

2. Hargis AM, Ginn PA. The integument. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:1066.

3. Jones TC, Hunt RD, King NW: Nutritional deficiencies. In: Veterinary Pathology, 6th ed, pp. 781-783, Maple Valley Press, Baltimore, MD 1997

4. Meyers RK, McGavin MD, Zachary JF. Cellular adaptations, injury, and death: morphologic, biochemical, and genetic bases. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:29-30.

5. McDowell EM, Shores RL, Spangler EF, Wenk ML, De Luca LM. Anomalous growth of rat incisor teeth during chronic intermittent vitamin A deficiency. J Nutr. 1987 Jul;117(7):1265-74.

6. Munday JS, McKinnon H, Aberdein D, Collett MG, Parton K, Thompson KG: Cystitis, pyelonephritis, and urolithiasis in rats accidentally fed a diet deficient in vitamin A. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 48: 790-794, 2009

7. Thompson K. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. vol. 1 Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:55-56.

8. Weber F: Biochemical mechanisms of vitamin A action. Proc Nutr Soc 42: 31-41, 1983

9. Zachary JF. Nervous system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012:865.