Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 9

30 October 2019

Frederic Hoerr, DVM, MS, PhD

Veterinary Diagnostic Pathology, LLC

638 South Fort

Valley Road

Fort Valley, Virginia, 22652 USA

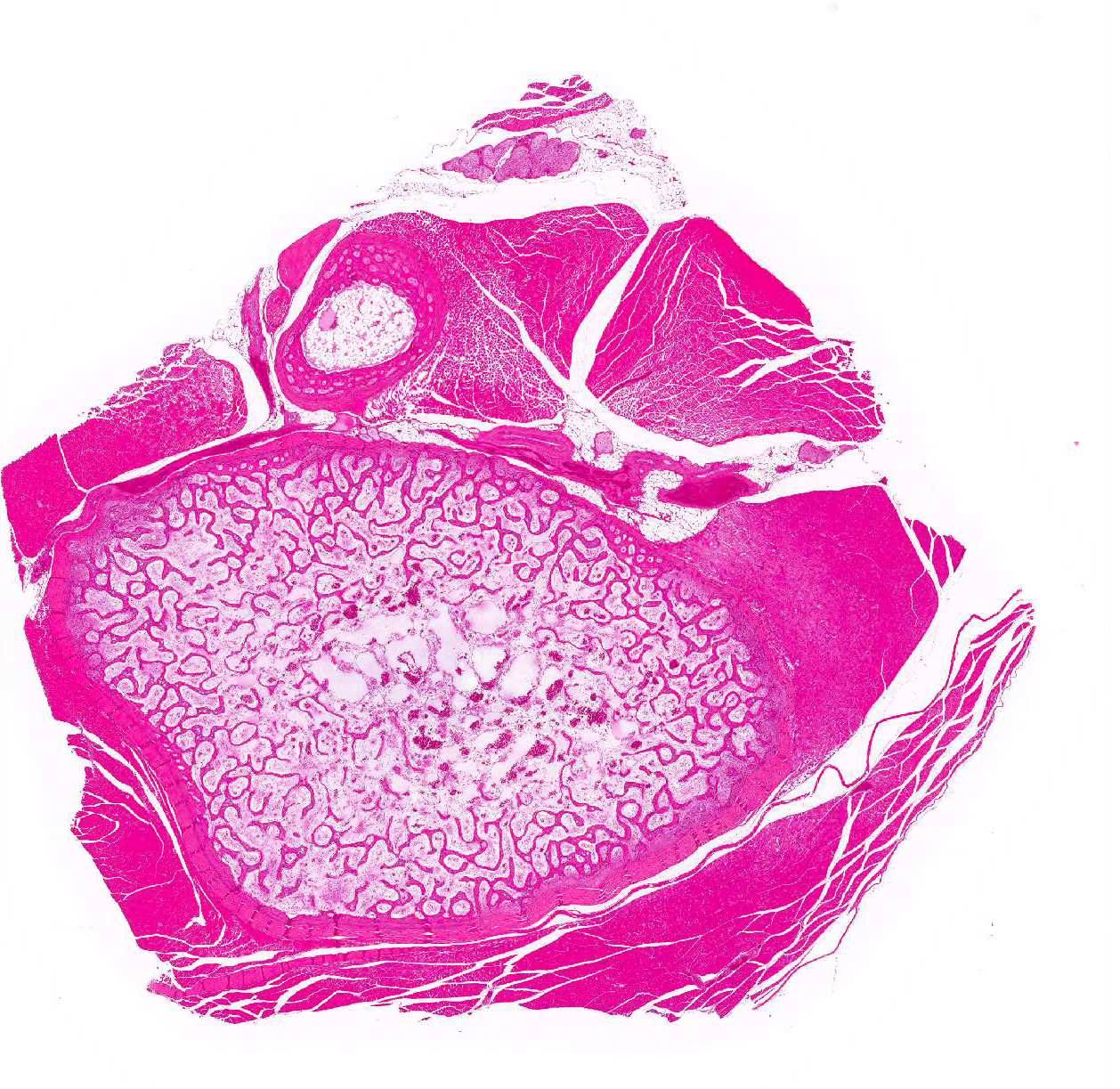

CASE II: 2018A (JPC 4134827).

Signalment: 14-day-old, female, SPF chicken (Gallus gallus)

History: A 1-day-old chick was inoculated intramuscularly with chicken anemia virus (CAV) that was isolated in Japan in 2017. The bird exhibited petechial hemorrhage of wings on 11 days post inoculation (DPI), depression and dropping wings on 12 DPI, and was found dead on 13 DPI.

Gross Pathology: The bone marrow, spleen and kidney were pale. The thymus was atrophied. The liver was enlarged.

Laboratory results: CAV was reisolated from the liver of the inoculated bird.

Microscopic Description:

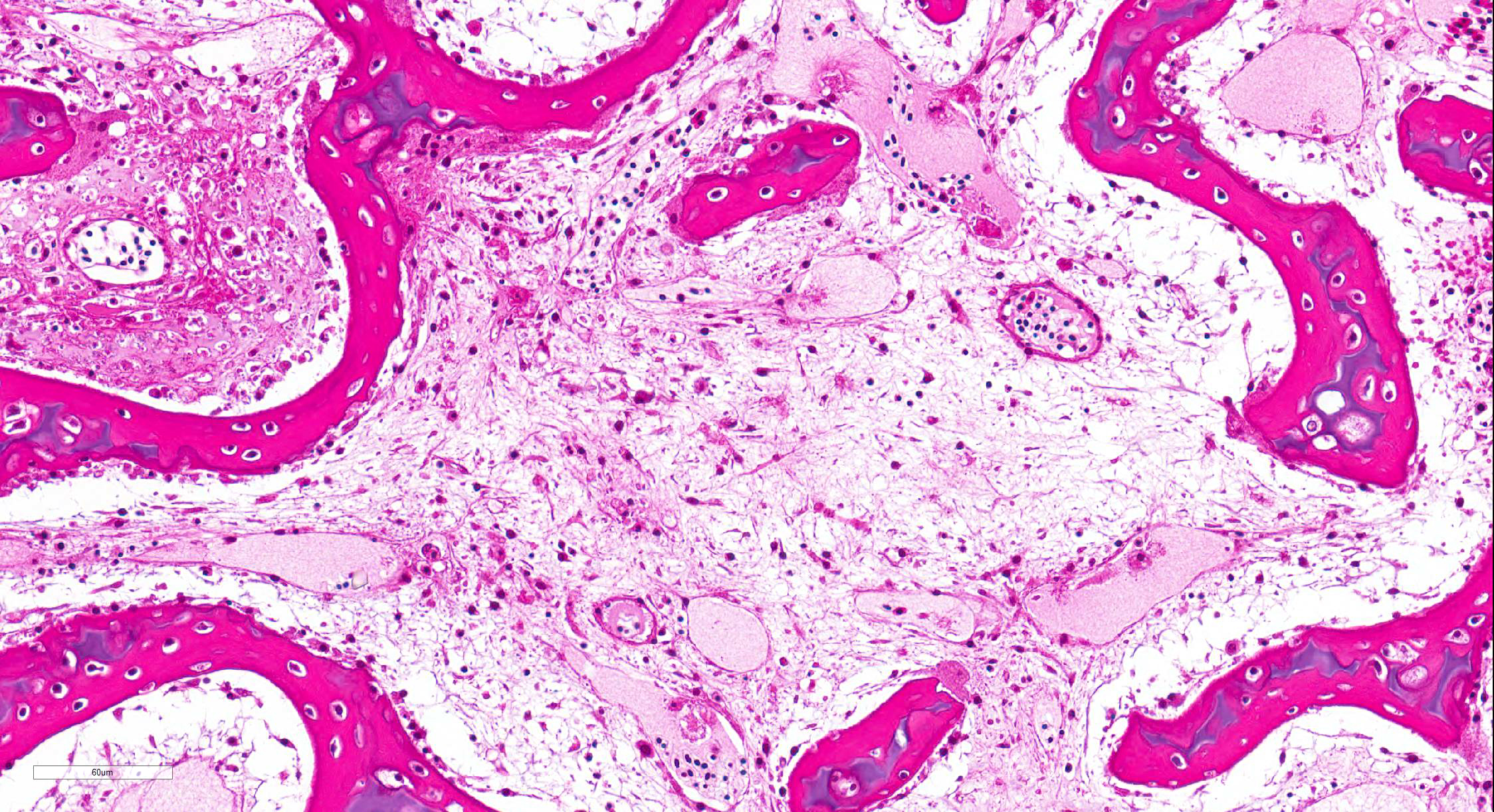

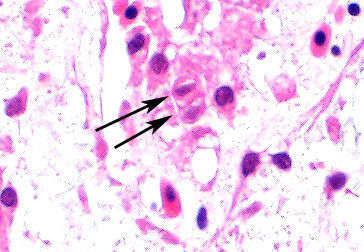

Bone marrow of tibiotarsus: Hematopoietic cells and erythrocytes were significantly decreased and were replaced by loose connective tissues. Low number of the large atypical cells were scattered in the extravascular spaces. Some of the atypical cells contained one to a few small eosinophilic nuclear inclusion bodies.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Bone marrow: Hypoplasia, severe, with occasional large atypical cells with small eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies.

Contributor Comment: The chicken anemia virus (CAV) was first detected in Japan in 1979.18 CAV currently belongs to the Gyrovirus genus, Anelloviridae family.9 CAV is a non-enveloped, icosahedral virus measuring about 19 nm in diameters, with a circular, single-stranded DNA genome.4,13,18 Chickens are considered only natural hosts of CAV. CAV is ubiquitous in flocks around the world, and most flocks carry antibodies regardless of vaccination.10-12,20

CAV is mainly transmitted vertically through eggs and causes anemia, anorexia and lethargy to chicks.19,21 Hematocrit values decline less than 10% of normal in severe cases.3,16 Infection with CAV alone in chickens of 2-week-old or older is subclinical.16 If clinical signs develops in these chicks, immune depression is suspected.6

CAV targets hemocytoblasts in the bone marrow and T lymphoblasts in the thymus cortex, leading to hypoplasia of the bone marrow and atrophy of the thymus lobules.1,2 Damage to the bone marrow and the lymphatic tissues causes anemia, circulatory failure and low platelets, and which develop the pale colored viscera and hemorrhagic lesions. The liver swelling and atrophy of the bursa of Fabricius can also be seen.17,18

Histologic findings include depletion of hematopoietic tissues in the bone marrow and depletion of lymphocytes in the lymphoid tissues.17 Eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion bodies can be observed in the bone marrow and the thymus of the infected birds.5 The inclusion bodies are occasionally detected in the spleen, proventriculus, lung, kidney, bursa of Fabricius and skin.15 CAV infection needs to be differentiated from infectious bursal disease (IBD). Infection of highly pathogenic IBD virus make lesions similar to CAV infection in lymphoid tissues, bone marrow and skeletal muscle.7,8,14 However, in IBD infection, inclusion bodies are not observed.

Contributing Institution:

National Institute of Animal Health,

National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO)

3-1-5Kannondai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 3050856, Japan

(WSC ID95)

http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/english/niah/index.html

JPC Diagnosis: Tibia, bone marrow: Necrosis (1pt.) and

atrophy, (1pt.) diffuse, severe with numerous hematocytic and

osteoclastic intranuclear viral inclusions.

JPC Comment: Chicken anemia agent is a major cause of immunosuppression in young chickens on a global basis, and is often associated with other diseases, such as necrotic dermatitis, hemorrhagic syndrome, aplastic anemia syndrome, and blue wing disease.

This slide is an excellent representation of the changes

noted in experimental infections with this agent. Following injection with a

virulent strain of CAV, bone marrow cellularity begins to decrease

approximately between 4-8dpi.5,15 Large hematopoietic cells, larger

than normal pre-erythroblasts are present within the intra- and extravascular spaces.

These cells frequently contain intranuclear inclusions, as do degenerating hematopoietic

cells. From days 12-20, (the time period from which this particular slide was

collected), there is severe depletion of both erythropoietic and granulocytic

cells. Inclusions may be more common seen in osteoclasts during this period,

as few hemocytic precursors remain.5 Similar changes proceed apace

along this timeline within the thymus, bursa, and splenic white pulp as well.

Intranuclear inclusions may be seen within lymphocytes in all of these tissues.15

In surviving birds, the bone marrow and lymphoid begin to repopulate by day

16dpi and day 24 dpi, with tissue recovery by day 32dpi.15 In one

study, 35 of 50 (70%) of inoculated birds succumbed to the disease, mostly

between days 14 and 18.17

The importance of infection with chick anemia agent is far more than early and permanent immunosuppression in chicks infected within the first few days of life. Earlier in the day, the moderator had presented a lecture on immunosuppressive disease suggesting that a second wave of immunosuppression may be seen in animals infected with chick anemia agents at approximately 18 days of age due to profound thymic atrophy. If injected later, it may also potentiate the effects of other immunosuppressive agent, such as IBD, resulting in significant immunosuppression and related diseases (reovirus, respiratory disease, clostridiosis, E. coli, coccidosis) in affected birds from 18-35 days.

The assembled participants discussed the difficulty of discerning the intranuclear inclusions in this disease. There was general agreement that they were in hemocytoblasts and osteoclasts, but agreement on what were inclusions and what were degenerating nuclei was more difficult to come by.

References:

1. Adair BM, McNeilly F, McConnell CD, McNulty MS. Characterization of surface markers present on cells infected by chicken anemia virus in experimentally infected chickens. Avian Dis. 1993; 37:943-950.

2. Adair BM. Immunopathogenesis of chicken anemia virus infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2000; 24:247-255.

3. Campbell TW, Ellis C. Appendices. In: Avian & exotic animal hematology & cytology. 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:246.

4. Goryo M, Suwa T, Matsumoto S, Umemura T, Itakura C. Serial propagation and purification of chicken anaemia agent in MDCC-MSBI cell line. Avian Pathol. 1987; 16:149-163.

5. Goryo M, Suwa T, Umemura T, Itakura C, Yamashiro S. Histopathology of chicks inoculated with chicken anaemia agent (MSB1-TK5803 strain). Avian Pathol. 1989; 18:73-89.

6. Imai K, Mase M, Tsukamoto K, Hihara H, Yuasa N. Persistent infection with chicken anaemia virus and some effects of highly virulent infectious bursal disease virus infection on its persistency. Res Vet Sci. 1999; 67:233-238.

7. Inoue M, Fukuda M, Miyano K. Thymic lesions in chicken infected with infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Dis. 1994; 38:839-846.

8. Inoue M, Fujita A, Maeda K. Lysis of myelocytes in chickens infected with infectious bursal disease virus. Vet Pathol. 1999; 36:146-151.

9. International committee on taxonomy of viruses

10. McNulty MS, Connor TJ, McNeilly F, Kirkpatrick KS, McFerran JB. A serological survey of domestic poultry in the United Kingdom for antibody to chicken anaemia agent. Avian Pathol. 1988; 17:315-324.

11. McNulty MS, Connor TJ, McNeilly F. A survey of specific pathogen-free chicken flocks for antibodies to chicken anaemia agent, avian nephritis virus and group a rotavirus. Avian Pathol. 1989; 18:215-220.

12. McNulty MS, Connor TJ, McNeilly F, Spackman D. Chicken anemia agent in the United States: isolation of the virus and detection of antibody in broiler breeder flocks. Avian Dis. 1989; 33:691-694.

13. McNulty MS, Curran WL, Todd D, Mackie DP. Chicken anemia agent: an electron microscopic study. Avian Dis. 1990; 34:736-743.

14. Nunoya T, Otaki Y, Tajima M, Hiraga M, Saito T. Occurrence of acute infectious bursal disease with high mortality in Japan and pathogenicity of field isolates in specific-pathogen-free chickens. Avian Dis. 1992; 36:597-609.

15. Smyth JA, Moffett DA, McNulty MS, Todd D, Mackie DP. A sequential histopathologic and immunocytochemical study of chicken anemia virus infection at one day of age. Avian Dis. 1993; 37:324-338.

16. Takagi S, Goryo M, Okada K. Pathogenicity for chicks of six isolation of chicken anemia virus (CAV) isolated in the past two years ('93 '94). J Jpn Soc Poulf Dis. 1996; 32:90-97.

17. Taniguchi T, Yuasa N, Maeda M, Horiuchi T. Hematopathological changes in dead and moribund chicks induced by chicken anemia agent. Natl Inst Anim Health Q (Tokyo). 1982; 22:61-69.

18. Yuasa N, Taniguchi T, Yoshida I. Isolation and some characteristics of an agent inducing anemia in chicks. Avian Dis. 1979; 23: 366-385.

19. Yuasa N, Yoshida I. Experimental egg transmission of chicken anemia agent. Natl Inst Anim Health Q (Tokyo). 1983; 23:99-100.

20. Yuasa N, Imai K, Tezuka H. Survey of antibody against chicken anaemia agent (CAA) by an indirect immunofluorescent antibody technique in breeder flocks in Japan. Avian Pathol. 1985; 14:521-530.

21. Yuasa N, Imai K. Pathogenicity and antigenicity of eleven isolates of chicken anaemia agent (CAA). Avian Pathol. 1986; 15:639-645.