Signalment:

Gross Description:

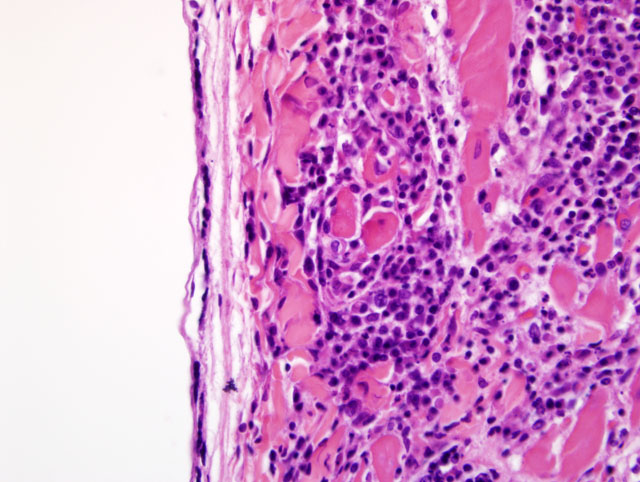

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Contributors Comment: Differential diagnoses for lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic myocarditis in dogs include a long list of potential infectious and parasitic pathogens. Viral pathogens include canine parvovirus 2, canine morbillivirus, canine and porcine herpesviruses, and West Nile Virus.(11) Canine morbillivirus is more likely to cause degenerative changes than the mononuclear inflammation seen in this case.Â

Bacterial causes can include a multitude of organisms which may eventually cause chronic mononuclear cell infiltration and myocardial degeneration; however, in most cases there is a significant suppurative component. Some of the more commonly reported organisms include Citrobacter spp. and Bartonella spp. (4,6) Borellia burdorferi is the most commonly reported spirochete capable of causing myocarditis in dogs.Â

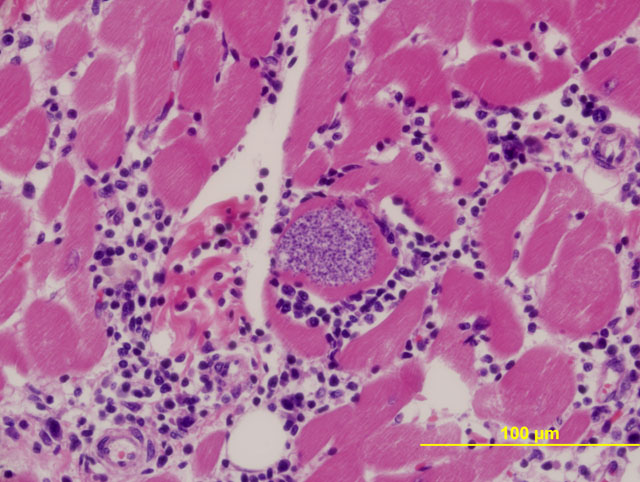

Fungal myocarditis has been reported in dogs associated with Cryptococcus neoformans, Coccidioides immitis, Blastomyces dermatidis, and Aspergillus terreus. Parasitic causes of myocarditis are also frequently reported and include Angiostrogylus vasorum (an eosinophilic component would be expected), and numerous protozoa. With the lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation seen in this case, protozoal myocarditis was considered the top differential. Reported causes of protozoal myocarditis include Toxoplasma gondii, Hepatozoan canis, Neospora canis, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Trypanosoma brucei.Â

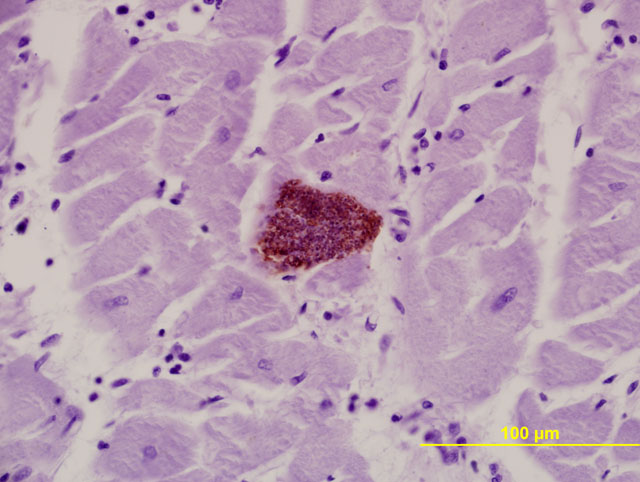

Immunohistochemical stains are available for the aforementioned protozoa. The morphology of protozoal amastigotes (with prominent kinetoplasts), intracardiomyocyte pseudocyst formation, and positive immunohistochemical staining for T. cruzi led to diagnosis of trypanosomiasis in this case.Â

Chagas disease is endemic to the southeastern United States and is considered an important differential for dogs with sudden death.(10) Widespread myocarditis can result in potentially fatal arrhythmias and/or cardiac contractile failure which can lead to peracute heart failure. One of the interesting features of the myocarditis and myocardial degeneration/necrosis seen in Chagas disease is that the most intense areas of inflammation and cardiomyocyte change are often unassociated with the parasite. Several studies have looked at the immunopathogenesis of Chagas disease and conclude that myocarditis may be a result of cell-mediated immune and/or autoimmune responses along with a microangiopathy.(1,2,5,9)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

T. cruzi, the cause of Chagas disease, is an extremely important disease in not only the southern United States, but also throughout Central and South America. It has been estimated that up to 10 million people in Central and South America have Chagas, a majority of which are unaware they are infected. Chagas disease is spread by insects from the Triatomidae family. These insects are also known as assassin bugs or kissing bugs. These bugs like to hide in the walls of mud huts to emerge at night for a blood meal. They feed near the oral or ocular mucous membranes, ingest a blood meal, and simultaneously defecate on their unfortunate victim. The person or animal bitten will scratch this area and introduce the trypomastigote form of T. cruzi into a mucous membrane or wound, and the organism enters the host. The trypomastigotes follow the blood stream to the heart, where they enter a cell and become amastigotes. This form multiplies by binary fission. Pseudocysts can be seen in cardiac myocytes at this stage. These cysts eventually rupture, releasing trypomastigotes. Trypomastigotes are taken up in the blood by the kissing bug, and in the intestinal tract the organism transforms into the epimastigote form. Once the organism travels to the rectal mucosa of the kissing bug, transformation back to the trypomastigote form occurs and the cycle continues.(3,7,8,9,12)

There is an acute phase of Chagas disease, characterized by nonspecific signs including fever, fatigue, diarrhea, and vomiting. Romanas sign, a characteristic swelling around the eye near the bite wound, is well recognized manifestation of this disease. The vast majority of people recover in 4-8 weeks. Several years later, a chronic phase develops in around 30% of those infected and manifests most commonly as a cardiomyopathy, or problems with the gastrointestinal system to include megaesophagus and megacolon. Less commonly it causes neurologic disease.(3,12)

Trypanosoma cruzi is a kinetoplastid, intracellular protozoan parasite. Ultrastructurally, the kinetoplast, which is a DNA-containing cytoplasmic organelle, can be used to identify protozoans. In Trypanosoma infections, the amastigotes have a kinetoplast that is parallel to the nucleus, whereas in Leishmania, the kinetoplast is smaller and is perpendicular to the nucleus. Other protozoans found in the heart, such as Toxoplasma and Neospora, do not have kinetoplasts.(7)

References:

2. Andrade ZA, Andrade SG, Correa R, Sadigursky M, Ferrans VJ: Myocardial changes in acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection ultrastructural evidence of immune damage and the role of microangiopathy. Am J Pathol, 144(6):1403-1411, 1994

3. Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML, Alcaraz A: Protozoans. In: Georgis Parasitology for Veterinarians, 8th ed., pp. 83-87. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2003

4. Breitschwerdt EB, Atkins CE, Brown TT, Kordick DL, Snyder PS. Bartonella vinsonii subsp. Berkhoffii and related members of the alpha subdivision of the Protobacteria in dogs with cardiac arrhythmias, endocarditis, or myocarditis. J of Clin Microbiol, 37(11):3618-3626, 1999

5. Caliari MV, de Lana M, Caja RAF, Carniero CM, Bahia MT, Santos CAB, Magalhaes GA, Sampaio IBM, Tafuri WL: Immunohistochemical studies in acute and chronic canine chagasic cardiomyopathy. Virchows Arch, 441:69-76, 2002

6. Cassidy JP, Callahan JJ, McCarthy G, OMahony MC: Myocarditis in sibling boxer puppies associated with Citrobacter koseri infection. Vet Pathol, 39:393-395, 2002

7. Cheville NF: Ultrastructural Pathology, pp. 716-721. Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa, 1994

8. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed., pp. 3-5. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1998

9. Golgher D, Gazzinelli RT: Innate and acquired immunity in the pathogenesis of chagas disease. Autoimmunity, 37(5):399-409, 2004

10. Kjos SA, Snowden KF, Craig TM, Lewis B, Ronald N, Olson JK: Distribution and characterization of canine Chagas disease in Texas. Vet Parasitol, 152:249-256, 2008

11. Lichtensteiger CA, Heinz-Taheny K, Osborne TS, Novak RJ, Lewis BA, Firth ML: West Nile Virus encephalitis and myocarditis in Wolf and Dog. Emerg Infect Dis, 9(10):1303-1306, 2003

12. McAdam AJ, Sharpe AH: Infectious disease. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, ed. Kumar V, Abbas AK, and Fausto N, 7th ed., pp. 405-406. Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, 2005