Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 11

5 December, 2018

CASE I: P15/141 JPC 4066260)

Signalment: 2.5-year-old, Aubrac bull, Bos taurus

History: The bull presented to Veterinary Teaching Hospital with history of chronic skin lesions of unknown reason.

Gross Pathology: Multifocal areas of alopecia

Laboratory results: PCR positive for B. besnoiti, ELISA positive for B. besnoiti

Microscopic Description:

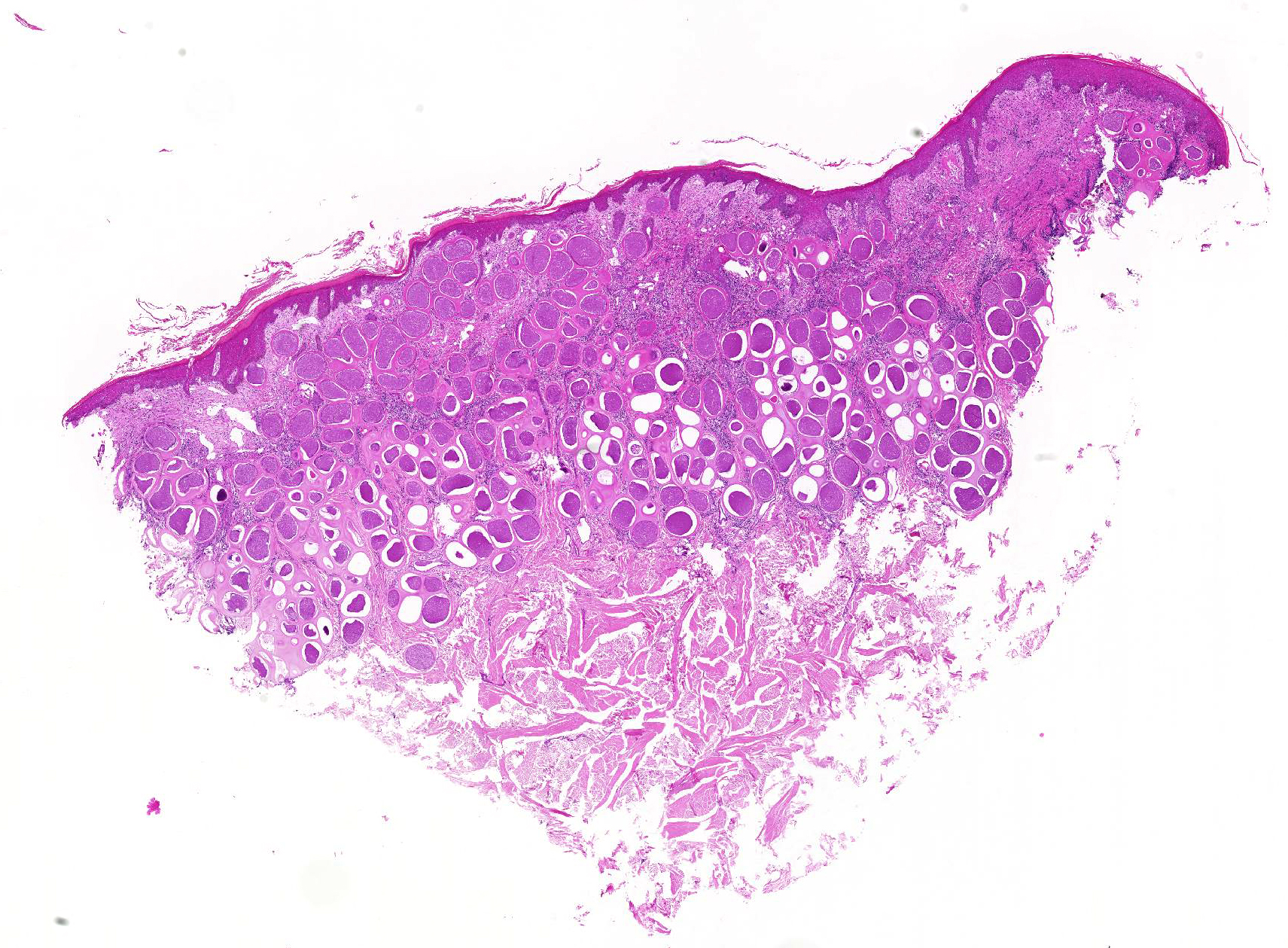

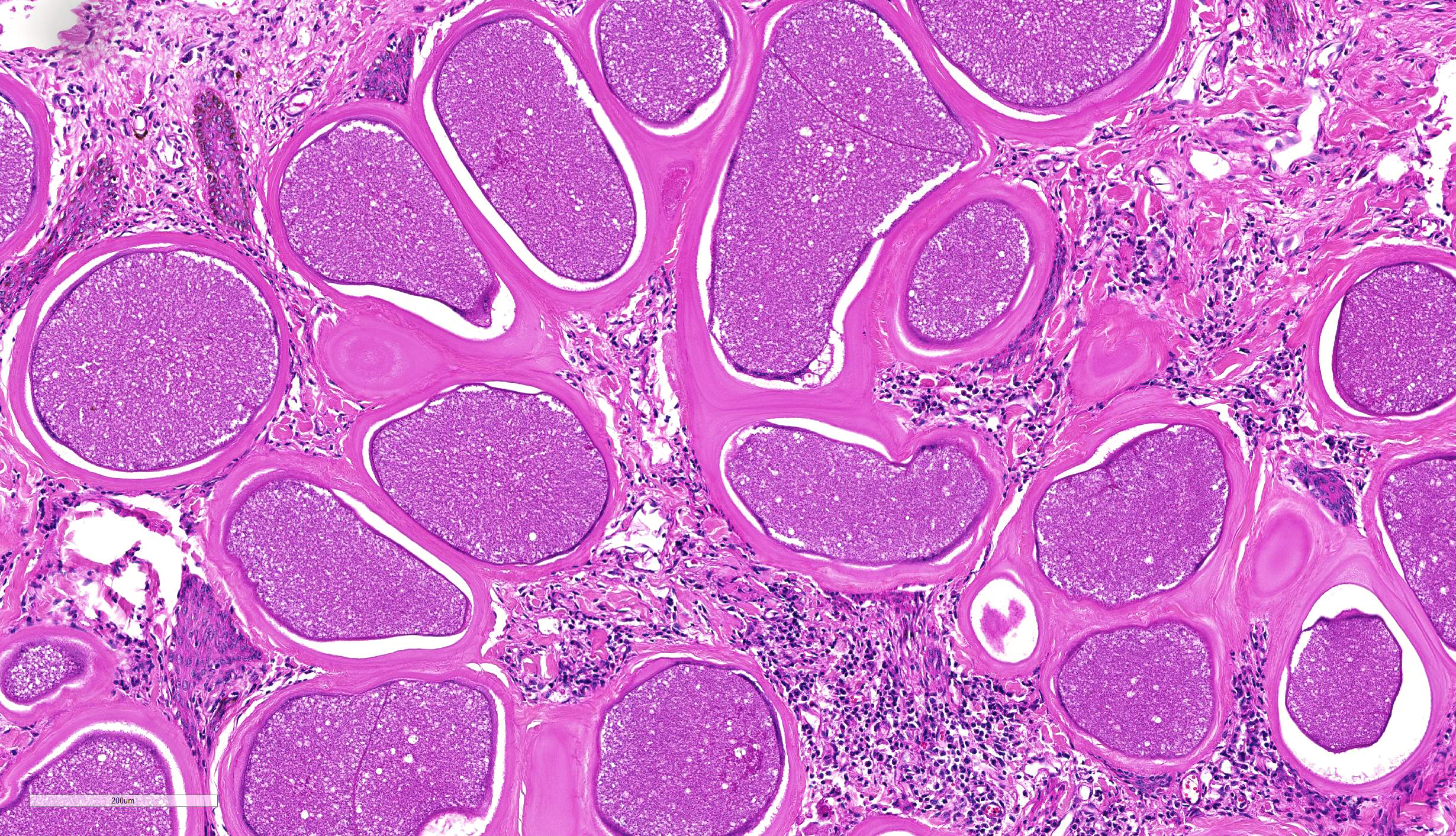

Haired skin. The epidermis displays low to moderate, diffuse, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, moderate, diffuse, epidermal hyperplasia characterized by acanthosis and irregular rete ridge formation, rare, multifocal, individual, intraepidermal macrophages, eosinophils and neutrophils (exocytosis), and rare, multifocal, discrete, shrunken, hypereosinophilic keratinocytes with pyknotic nuclei (apoptosis). The superficial dermis and a variable part of the adjacent deep dermis are markedly and diffusely expanded by a moderate, coalescing, perivascular, and nodular to diffuse infiltration of macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophilic granulocytes and to a locally variable extent also neutrophilic granulocytes, as well as a low to moderate, coalescing amount of bundles of fibroblasts and fibrocytes within a collagenous stroma (fibrosis). There is a marked coalescing to diffuse loss of follicular and adnexal structures (alopecia). Within the superficial and upper deep dermis are numerous round protozoal cysts characterized by a diameter of ~ 250 µm, a ~ 12 µm thick, distinctly bordered, pale eosinophilic, hyaline outer capsule, a subcapsular ~ 10 µm thick ring of eosinophilic cytoplasm containing multiple fusiform nuclei, and a central round vacuole containing myriads of densely packed, ~ 4 µm in diameter, distinctly bordered, crescent-shaped bradyzoites with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and a central, hyperchromatic nucleus. The dermal collagenous stroma, adjacent to the cysts show a mild, laminar zone of shrinkage and hypereosinophilia (compression atrophy).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Haired skin. Dermatitis nodular to diffuse, granulomatous and eosinophilic, chronic, coalescing, moderate with numerous intradermal, intracellular, apicomplexan cysts (etiology consistent with Besnoitia besnoiti), adjacent laminar compression atrophy, dermal fibrosis, alopecia, epidermal hyperplasia and orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis.

Contributor’s Comment: Etiology: The apicomplexan protozoan parasite Besnoitia besnoiti (B. besnoiti; Family: Sarcocystidae) is the etiologic agent of bovine besnoitiosis (Synonyms: bovine cutaneous globidiosis, bovine cutaneous sarcosporidiosis, elephant skin disease of cattle) and has been described first by Cadéac in 1884.1 The closely related Besnoitia species B. caprae, B. bennetti and B. tarandi induce a comparable disease mainly in goats, equids and wild ruminants, respectively (Table 1).11

Besnoitiosis is an endemic disease in the southern part of Europe, the subtropical areas of Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, but has also been reported as an emerging disease in the central and northern part of Europe.1,5,7,8 In endemic areas seroprevalence rates are ~ 50% whereas the incidence of clinical cases of 1-10% per year, as well as the mortality rate of less than 1% are obviously low. Prevalence and incidence may be higher in areas where the disease is emerging.1,11

B. besnoiti is commonly believed to have a heteroxenous life cycle, however until today only homoxenous transmission from intermediate to intermediate host has been shown experimentally. The most important intermediate host are cattle, but wildebeest, kudu and impala are also affected.11 The epidemiological importance of wild ruminants in northern Europe is currently unknown. Although roe deer and red deer can be seropositive in areas of endemic bovine besnoitiosis, the strong cross reactivity of B. besnoiti, B. tarandi and B. bennetti prevents differentiation of these species employing serological methods.6 Although many authors have suggested that the final host of B. besnoiti could be the domestic cat or wild carnivores, attempts to proof this hypothesis have been unsuccessful so far.10 Therefore the final host of B. besnoiti remains currently unknown, as is true for most other species of the genus Besnoitia (Table 1). Whether transmission from the currently unknown definitive host to the intermediate host occurs in via oocytes shed in the feces remains unknown. In contrast, horizontal mechanical transfer between intermediate hosts by blood-sucking insects including tsetse flies (Glossina brevipalpis), tabanids (Tabanocella denticornis, Atylotus nigromaculatus, Haematopota albihirta), mosquitoes (Culex simpsoni, Culex spp.) and stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) has been experimentally proven and is suggested to be an important mode of transmission.5 Furthermore, transmission by other arthropods, iatrogenic transfer and direct contact including sexual transfer are possible other routes of transmission.1

Rapid asexual intracellular proliferation of B. besnoiti tachyzoites occurs mainly within the intermediate host´s endothelial cells during the acute phase after the first infection. This leads to vasculitis and thrombosis of capillaries and smaller veins, especially within the dermis, and subsequent generalized subcutaneous edema.2,8 One to two weeks after the onset of the acute phase, the infection reaches the subacute to chronic stage which is characterized by evolving intracellular tissue cysts containing myriads of bradyzoites within vimentin-positive, MAC387-negative, mesenchymal cells (suggested to be fibroblasts or myofibroblasts), especially within the dermis and submucosa, as well as various other tissues.8 A detailed description of the sequential steps of tissue cyst formation can be found in Langenmayer et al. (2015).8

The clinical disease can be subdivided into two phases. The acute phase (“anasarca phase”) of bovine besnoitiosis occurs 11-13 days after infection and lasts for 6-10 days, and is characterized by fever, subcutaneous edema, lymphadenitis, conjunctivitis, nasal discharge, salivation, laminitis and depression.2,8

In contrast, the chronic phase (scleroderma phase) is characterized by macroscopically detectable tissue cysts in connective tissues, especially the pathognomonic pin-head sized cysts in the dermis and submucosa of conjunctiva, nasal cavity and vagina, as well as lichenification, hyperkeratosis and alopecia.5,8

Overt clinical disease most often affects 2- to 4-year old adults and chronically infected animals may partially recover but are thought to remain infected for the rest of their lifes.1 Although only a small percentage of less than 1% of the affected cattle die, bovine besnoitiosis may lead to major economic losses due to weight loss and decreased milk production, abortion, male infertility, and reduced value of the hides. Currently there are no therapeutic treatment options available. An attenuated live vaccine is available in some countries for prophylaxis.

Macroscopic changes in the acute phase of besnoitiosis are rather unspecific and include coalescing to generalized subcutaneous edema (anasarca), multifocal to coalescing, lymphohistioplasmacytic and eosinophilic perivascular dermatitis, dermal hemorrhages, generalized swelling of lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), and swollen testicles (orchitis).2,8 The characteristic tissue cysts start to develop in the subacute stage concurrent with the decline of dermal edema. The tissue cysts become clearly macroscopically visible as pin-head sized, pearl white tissue cysts with a diameter of up to 1 mm within the conjunctiva and mucous membranes of the vagina, nose, pharynx and upper respiratory tract in the chronic phase of besnoitiosis.8 The dermis exhibits multifocal to coalescing palpable indurations with a diameter of initially 3-5 mm and later up to 1 cm, especially at the teats, eyelids, neck and limbs, as well as hypotrichosis, alopecia, seborrhea, lichenification and partially erosions, exudations and crusts. Other affected tissues include the connective tissue of the subcutis, intermuscular fascia, mesentery and scrotum.2,4,5

Histologically, crescent-shaped 6-7,5 x 2,5-3,9 µm sized B. besnoiti tachyzoites with eosinophilic cytoplasm and a round basophilic nucleus may be visible within endothelial cells, blood and lymph vessels, and extracellular spaces during the acute stage. Notably, these tachyzoites are indistinguishable from Neospora caninum or Toxoplasma gondii by light microscopy.2,4,8

The B. besnoiti tissue cysts of the chronic phase exhibit a diameter of up to 600 µm, and a characteristic double-walled morphology which allows differentiation from the similar cysts of Sarcocystis spp. and Eimeria spp.11 The outer 10-12 µm, pale eosinophilic, hyaline cyst wall is comprised of host-derived collagenous material and its outer surface blends irregularly into the surrounding connective tissue. The inner cyst wall is a thin pale gray-bluish band with distinct histochemical staining characteristics in between the outer cyst wall and the outer cell membrane of the host cell. The outer cyst wall stains blue with Masson´s trichrome and pale white with Giemsa stain, whereas the inner cyst wall stains pale white with Masson´s trichrome stain and deeply violet with Giemsa stain.8 The large host cell is multinucleated and forms a peripheral rim of cytoplasm, which in turn encompasses the central parasitophorous vacuole. The parasitophorous vacuole is filled with thousands of 6,0-7,5 x 1,9-2,3 µm sized bradyzoites.2 The cysts are often surrounded by a granulomatous and eosinophilic, nodular to diffuse dermatitis with fibrosis, compression atrophy of adnexa, and hyperkeratosis.4,7 Occasional multinucleated giant cells of the foreign body type can be present in the inflammatory infiltrate.8 Other lesions include focal or multifocal myositis, keratitis, periostitis, endosteitis, lymphadenitis, pneumonia, periorchitis, orchitis, epididymitis, arteritis, perineuritis, and laminitis.4,8

A comprehensive ultrastructural description of the tachyzoites, bradyzoites and tissue cysts in bovine besnoitiosis has been published recently.9

The gold standard for the diagnosis of bovine besnoitiosis seems to be the histologic demonstration of the pathognomonic Besnoitia spp. tissue cysts. Obvious microscopic differentials for B. besnoiti include the indistinguishable cysts other species of the genus Besnoitia as well as the confusable cysts of Sarcocystis spp., Eimeria spp., and the sporangia of the fungal agents Rhinosporidium seeberi, Emmonsia crescens, Sporothrix schenkii, Coccidioides immitis and Loboa loboi.3

Immunohistochemistry can be used to differentiate B. besnoiti bradyzoites and cysts from those of Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum and, although with minor cross reactivity, also Sarcocystis spp.8 Due to the serological cross reactivity of the various species of the genus Besnoitia, it seems reasonable that it is also not possible to differentiate between these species using immunohistochemistry.6 Therefore molecular genetic methods are the method of choice if a diagnosis at the species level is needed.11

Table 1. Species of the genus Besnoitia and their main hosts.

|

Species name |

Main intermediate host |

Main final host |

|---|---|---|

|

Besnoitia besnoiti |

Cattle, kudu, blue wildebeest, impala |

? |

|

Besnoitia caprae |

Goat |

? |

|

Besnoitia tarandi |

Reindeer, caribou, mule deer, roe deer, muskox |

? |

|

Besnoitia bennetti |

Horse, donkey, mule, (zebra) |

? |

|

Besnoitia jellisoni |

Mouse, rat, other rodents |

? |

|

Besnoitia akodoni |

Montane grass mouse |

? |

|

Besnoitia oryctofelisi |

Rabbit |

Cat |

|

Besnoitia darlingi |

Virginia opossum |

Cat |

|

Babesia neotomofelis |

Southern planes woodrat |

Cat |

|

Besnoitia wallacei |

? |

Cat |

Data based on the review of Olias et al. (2011).11

Contributing Institution:

Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany (www.fli.bund.de)

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin: Dermatitis, lymphoplasmacytic, histiocytic, and eosinophilic, diffuse, moderate, with numerous apicomplexan cysts and mild diffuse epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided a thorough discussion of this disease which is currently considered of great economic importance in cattle in Europe. Historically, the disease was first described by Cadeac in 1884 and named “Telephanitiasis el l”anasarque du bouef.’ Although initially misdiagnosed by Besnoit (a professor of veterinary medicine in Toulouse) and Robin as a species of Sarcocystis (S. besnoiti) in 1912, and in 1916, Franco and Borges proposed the name Besnoitia besnoiti. The disease is gone by many names, including bovine subcutaneous globidiosis, bovine cutaneous cervical spongiosis, and elephant skin disease of cattle.

While the definitive host of B besnoiti remains unproven, domestic and wild felines have been shown to be the definitive host for Besnoitia species of rodents. A recent publication by Verma et al. has identified the bobcat (Lynx rufus) as the definitive host of B. darlingi, a species which parasitizes the opossum.

While orchitis and a marked decrease in fertility in bulls has been well documented this disease, chronically infected cows may still become pregnant, and give birth, with no reports to date of vertical transmission of B. besnoiti. Subsequent rearing is problematic, as the disease causes a negative impact on milk production, as well as the calf’s nursing opening painful wounds on infected teats.2 Another clinical finding in chronic cases of disease in cattle include laminitis, likely as a result of interference with dermal vasculature and pressure put on epidermal laminae by the presence of tissue cysts. Inappropriate weight bearing ultimately results in rotation of P3 and the development of sole ulcers.5

On a microscopic level, the composition of the two cysts walls, the inner cyst wall (which lies outside the host cell membrane), and the hyalin outer cyst wall (composed of type I collagen as evidenced by a deep blue staining on a Masson’s trichrome and orange birefringence on picrosirius red), was recently described by Langenmeyer et al. The pale white staining of the ICW on Masson’s and a blue-green color in picrosirius red/Alcian blue strongly suggests that the ICW is composed of elements of the extracellular matrix. This interesting histochemical discovery further supports myofibroblasts as the cell of origin for tissue cysts as myofibroblasts are capable of producing both extracellular matrix components as well as type I collagen.

To date, no member of the genus Besnoitia have been demonstrated to elicit disease in humans.

References:

- Alvarez-Garcia G, Frey CF, Mora LM, Schares G: A century of bovine besnoitiosis: an unknown disease re-emerging in Europe. Trends Parasitol 2013:29(8):407-415.

- Cortes H, Leitao A, Gottstein B, Hemphill A: A review on bovine besnoitiosis: a disease with economic impact in herd health management, caused by Besnoitia besnoiti (Franco and Borges, ). Parasitology 2014:141(11):1406-1417.

- Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1998.

- Ginn PE, Mensett JEKL, Rukich PM: Skin and appedages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer´s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5 ed.: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: 556-781.

- Gollnick NS, Scharr JC, Schares G, Langenmayer MC: Natural Besnoitia besnoiti infections in cattle: chronology of disease progression. BMC Vet Res 2015:11(1):35.

- Gutierrez-Exposito D, Ortega-Mora LM, Marco I, Boadella M, Gortazar C, San Miguel-Ayanz JM, et al.: First serosurvey of Besnoitia spp. infection in wild European ruminants in Spain. Vet Parasitol 2013:197(3-4):557-564.

- Hornok S, Fedak A, Baska F, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Basso W: Bovine besnoitiosis emerging in Central-Eastern Europe, Hungary. Parasit Vectors 2014:7:20.

- Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Majzoub-Altweck M, Scharr JC, Schares G, Hermanns W: Naturally acquired bovine besnoitiosis: histological and immunohistochemical findings in acute, subacute, and chronic disease. Vet Pathol 2015:52(3):476-488.

- Langenmayer MC, Gollnick NS, Scharr JC, Schares G, Herrmann DC, Majzoub-Altweck M, et al.: Besnoitia besnoiti infection in cattle and mice: ultrastructural pathology in acute and chronic besnoitiosis. Parasitol Res 2015:114(3):955-963.

- Millan J, Sobrino R, Rodriguez A, Oleaga A, Gortazar C, Schares G: Large-scale serosurvey of Besnoitia besnoiti in free-living carnivores in Spain. Vet Parasitol 2012:190(1-2):241-245.

- Olias P, Schade B, Mehlhorn H: Molecular pathology, taxonomy and epidemiology of Besnoitia species (Protozoa: Sarcocystidae). Infect Genet Evol 2011:11(7):1564-1576.

- Verma SK, Cerquieria-Cezar CK, Murata FHA, Loavallo MJ, Rosenthal BM, Dubey JP. Bobcats (Lynx rufus) are natural definitive hosts of Besnoitia darlingi. Vet Parasitol 2017; 248:84-89.