Signalment:

Gross Description:

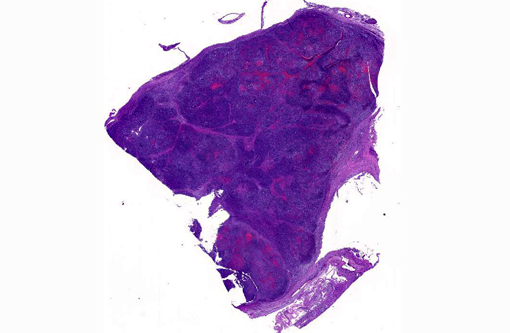

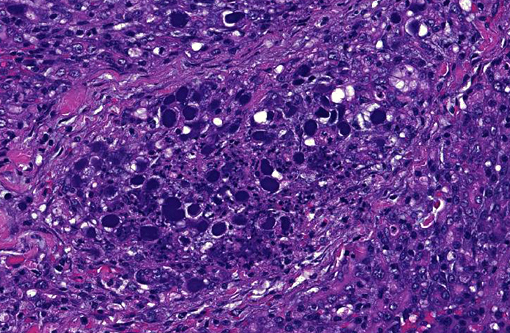

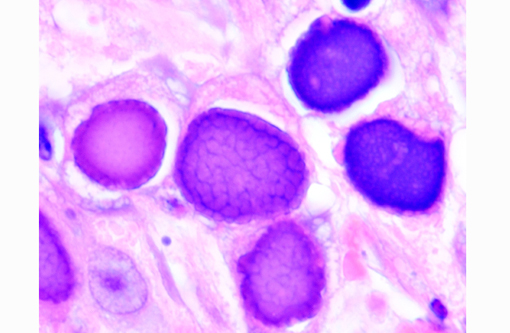

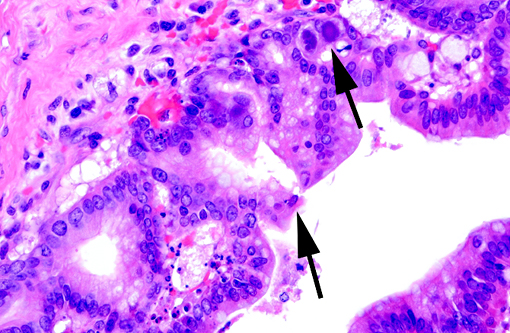

Histopathologic Description:

In addition, some lobules not completely necrotic demonstrate prominent regenerative hyperplasia with some atypia. Islet cell structures were infrequently observed and when visible, did not have evidence of primary viral cytopathic effect.

Although the organ was extensively effaced by this necrotizing process, there were small, patchy remaining areas of relatively normal appearing parenchyma (not generally seen in sections distributed). In some sections, overlying pancreatic capsule was markedly thickened and fibrotic, with infrequent fibrous adhesive tags.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Adenovirus has been isolated from a wide variety of tissues from healthy monkeys(6) and consensus suggests that these viruses usually exist in a latent state, only rarely causing disease,(3) although fatal adenoviral pneumonia has been encountered in a wide range of simian primates.(10) The immunofluorescent-demonstrated presence of duodenal adenovirus antigen was documented in two cases of monkeys with adenoviral pancreatitis and this, along with the common concurrent presence of clinical enteric disease suggests that pancreatic infection may occur from GI ascension through pancreatic ducts.(3) Adenovirus enteritis has been documented in SIV infected Rhesus monkeys.(6)

Necrotizing pancreatitis in animals is not typically associated with an infectious pathogenesis. Foals have been reported to have naturally occurring adenoviral pancreatitis, although this appears as part of a widespread infection with primary lung and other tissue involvement.(13) Experimental pancreatitis has been induced in mice with a wide variety of viruses including Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMC), Reovirus, Coxsackie B virus, Foot and Mouth Disease virus, Venezuelan Equine Encephalomyelitis virus and others.(5,7) Economou & Zissis and others have enumerated infectious causes of acute pancreatitis in humans,(1,4) including multiple viruses such as Mumps, Coxsackie B virus and Hepatitis B virus, although it appears that many of these associations are based on antibody titer presence, clinical presentation and the exclusion of other known causes.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Adenoviruses eject DNA from the viral capsid and into the nucleus, where subsequent DNA and protein synthesis create the distinctive inclusions and ultimately result in death of the cell. Ultrastructurally, the inclusions are composed of prominent paracrystalline arrays of virions and unassembled capsid proteins. Respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelial cells are the most common targets of viral replication; however, the epithelial cells of the conjunctiva, cornea, urinary bladder, and kidney, in addition to hepatocytes and pancreatic acinar cells, can also be infected. Although adenoviral inclusions are generally quite distinctive, they can resemble those of cytomegalovirus (herpesvirus) and SV40 (polyomavirus), which also cause significant cytomegaly and nucleomegaly.(14)

References:

1. Adler JB, Mazzotta SA, Barkin JS. Pancreatitis caused by measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (Case report). Pancreas. 1991;6:489-490.Â

2. Baskin GB, Murphey-Corb, M, Watson A, Martin LN. Necropsy findings in Rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with cultured Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV)/Delta. Vet Pathol. 1988;25:456-467.Â

3. Baskin GB, Soike KF. Adenovirus Enteritis in SIV-infected Rhesus monkeys. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1989;160(5):905-906.

4. Boyce JT, Giddens WE, Valerio M. Simian adenoviral pneumonia. Am J of Path. 1978;91(2):259-276.

5. Chandler FW, Callaway CS, Adams SR. Pancreatitis associated Adenovirus in a Rhesus monkey. Vet Pathol. 1974;11:165-171.

6. Chandler FW, McClure HM. Adenoviral Pancreatitis in Rhesus monkeys: current knowledge. Vet Pathol. 1982;19(Supp. 7):171-180.

7. Craighead JE, Kanich RE, Kessler JB. Lesions of the Islets of Langerhans in Encephalomyocarditis virus infected mice with diabetes mellitus-like disease. Am J of Path. 1974;74(2):287-294.

8. Daniel MD, Desrosiers RC, Letvin NL, King NW, Schmidt DK, Sehgal P, Hunt RD. Simian models for AIDS. Cancer Detection and Prevention Supplement. 1987;1:501-507.

9. Daniel MD, Letvin NL, Sehgal PK, Desrosiers RC, Hunt RD, Waldron LM. Induction of AIDS-like disease in macaque monkeys with T-Cell tropic retrovirus STLV-III. Science. 1985;230:71.

10. Economou M, Zissis M. Infectious cases of acute pancreatitis. Annals of Gastroenterology. 2000;13(2):98-101.

11. Martin BJ, Dysko RC, Chrisp CE. Pancreatitis associated with Simian Adenovirus 23 in a Rhesus monkey. Laboratory Animal Science. 1991;41(4):382-384.

12. McClure HM, Chandler FW, Hierholzer JC. Necrotizing pancreatitis due to Simian Adenovirus Type 31 in a Rhesus monkey. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1978;102:150-153.

13. McChesney AE, England JJ, Adcock JL, Stackhouse LL, Chow TL. Adenoviral infection in suckling Arabian foals. Vet Pathol. 1970;7:547-565.Â

14. Wachtman L, Mansfield K. Viral diseases of nonhuman primates. In: Abee CR, Mansfield K, Tardif S, Morris T, eds. Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2012:28-30.