Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 24

May 2nd, 2018

CASE III: 68197 (JPC 4084211)

Signalment: Nine-month-old, male, Meller’s chameleon (Trioceros melleri), reptile.

History: A cohort of five Meller’s chameleons (two male, three female) were group-housed in an outdoor zoological exhibit for approximately five months during the summer. One month prior to presentation, they were moved to an indoor enclosure for the winter. Routine complete blood cell count and serum chemistry panels performed two months prior to presentation were unremarkable.

All five animals died within a span of one month. The first mortality occurred without premonitory signs. One week later, three other individuals in the group presented with acute onset dehydration, lethargy and anorexia. Despite supportive care and environmental changes, these three individuals became moribund and were euthanized ten days after presentation. Two days later, the final group member exhibited intermittent mouth gaping, decreased appetite, and a cutaneous vesicle near the tail base. Blood work performed at that time showed hyperglycemia, hyperphosphatemia, and a leukocytosis with reactive heterophils and monocytes. Despite gavage feedings and treatment with famcylcovir, ceftazadime, subcutaneous fluids, and meloxicam the animal developed serous oculonasal discharge and multifocal oral and dermal petechiae, and was found dead 10 days after onset of clinical signs.

Gross Pathology: All animals presented in thin body condition. The first four animals did not have any other significant gross findings, while the fifth animal exhibited mild transudative coelomic effusion and petechial hemorrhages affecting the tongue and kidneys.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): Fixed liver tissue from the first chameleon and a pooled sample of fresh frozen liver from the following three chameleons were sent to the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research for Ranavirus qPCR testing. All samples were positive for Ranavirus. PCR and sequencing of the neurofilament-like and major capsid protein genes further identified the virus as a member of the Frog Virus 3 (FV3) group.

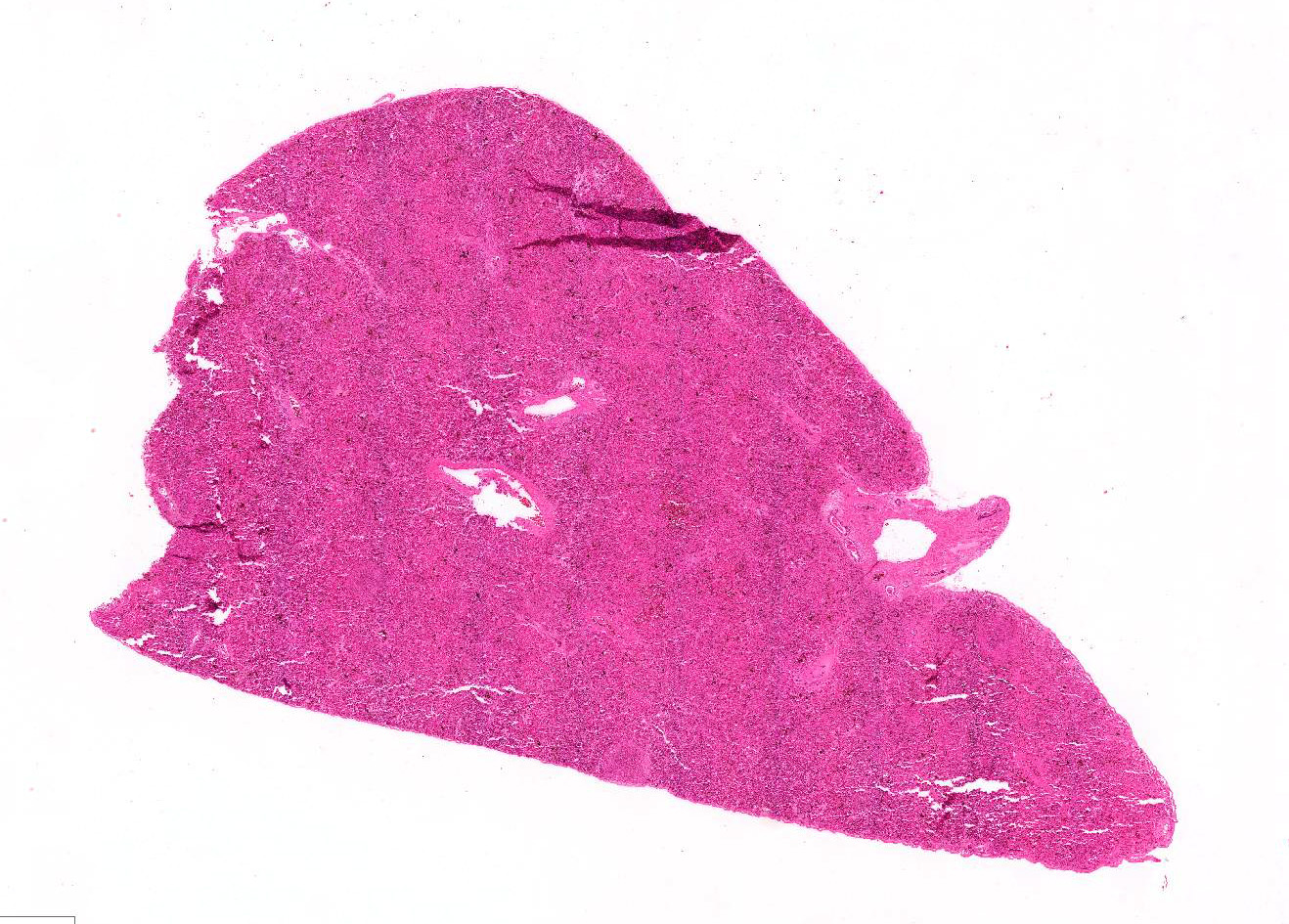

Microscopic Description:

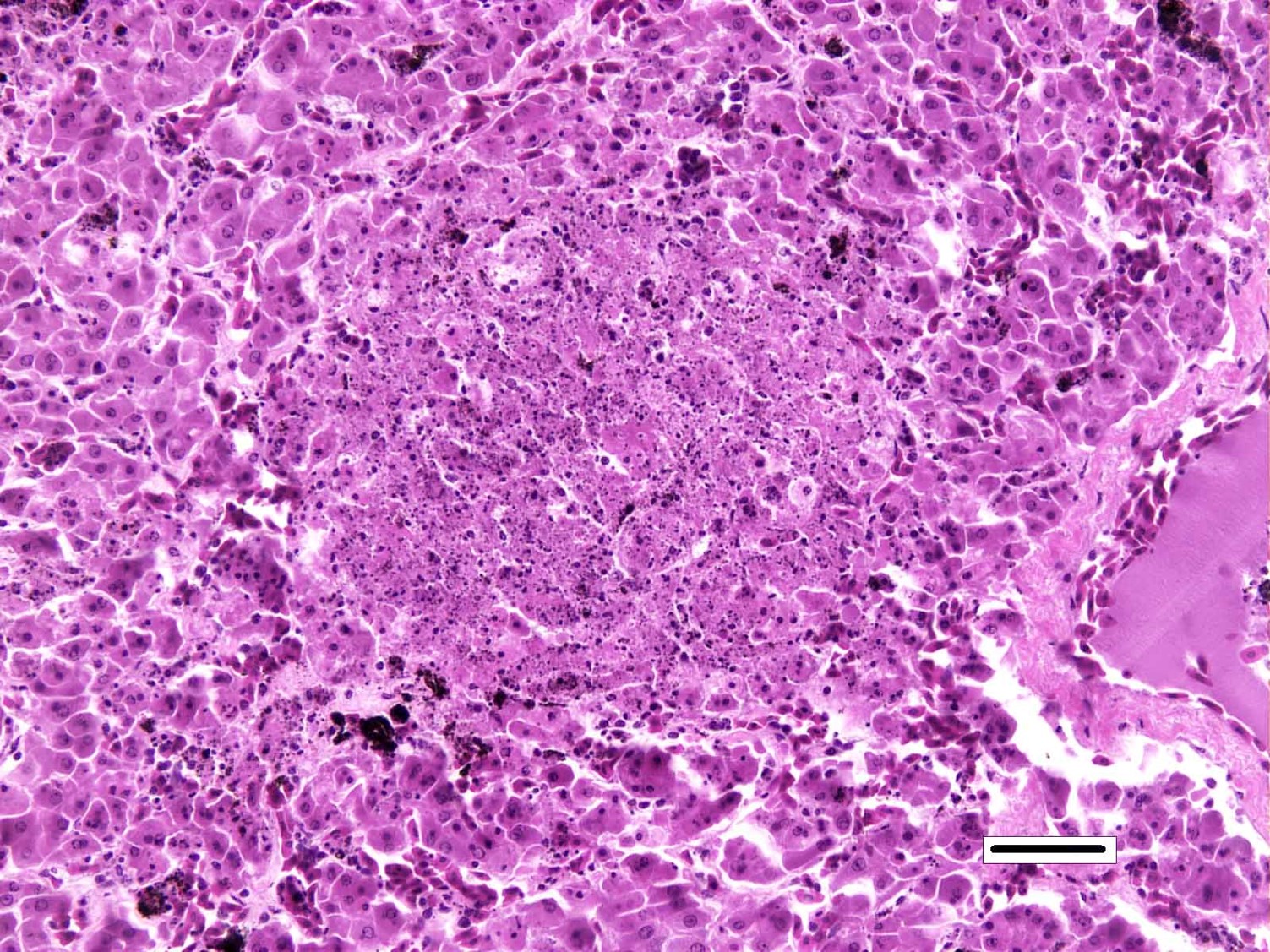

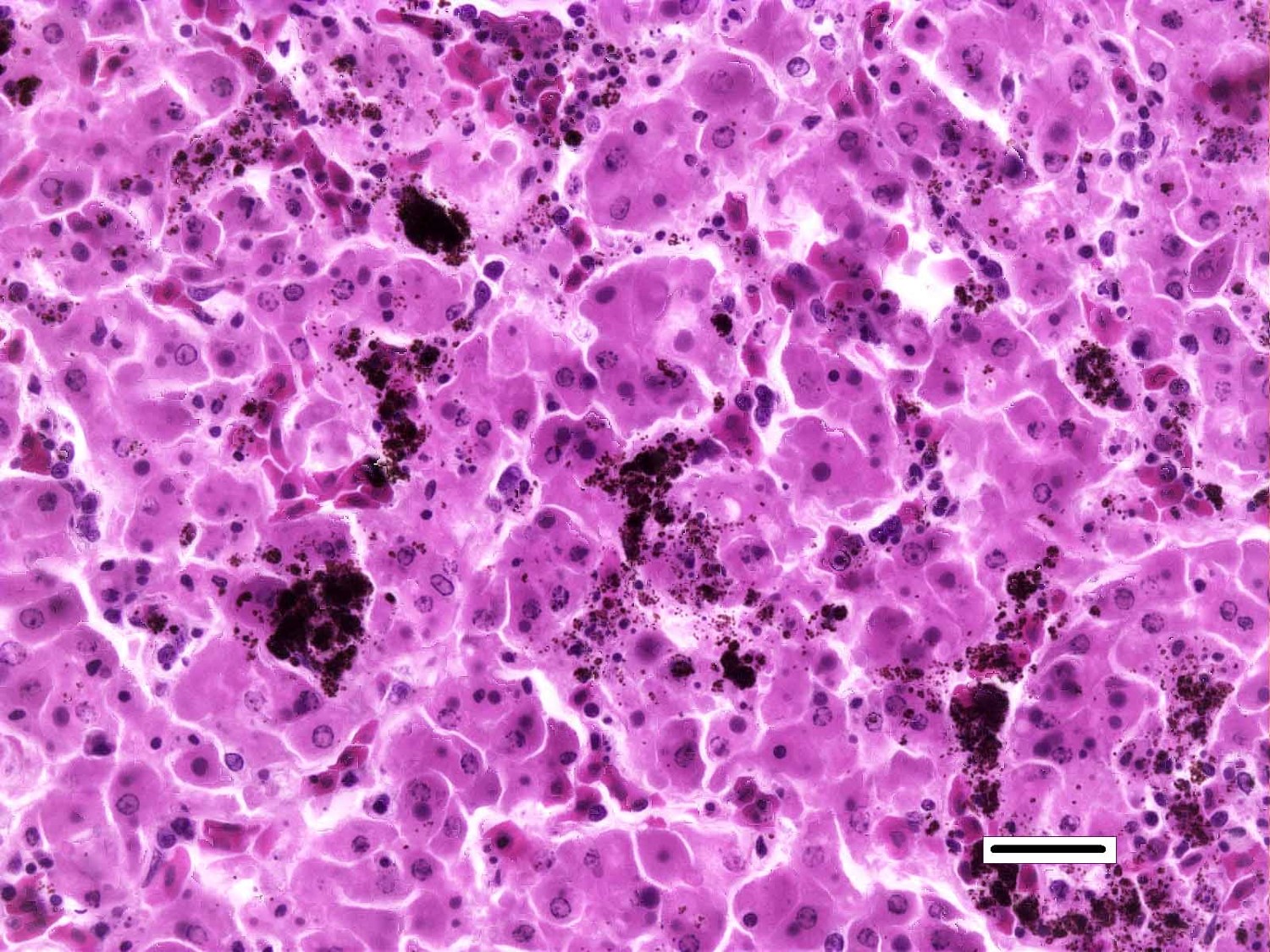

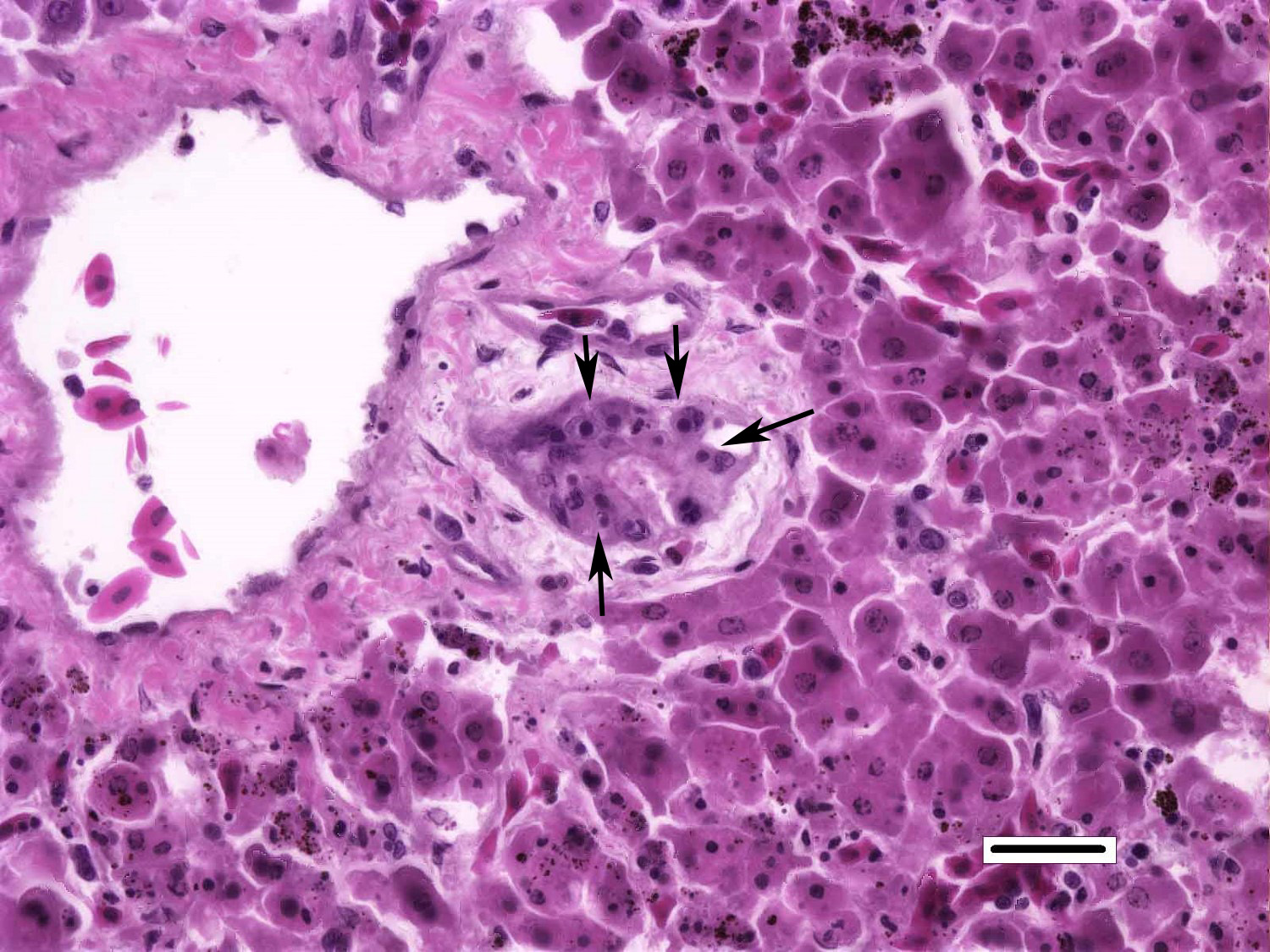

Liver: Randomly distributed throughout the hepatic parenchyma are numerous, variably-sized areas of necrosis characterized by disruption of chordal architecture and replacement by eosinophilic and karyorrhectic debris admixed with fibrin, mild hemorrhage, and dark brown to black granular material (presumptive melanomacrophage granules). Adjacent hepatocytes are often shrunken and hypereosinophilic with pyknotic to faded nuclei. Throughout the section, hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells frequently contain one to multiple, variably-sized, basophilic intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies. Biliary epithelial cells are also multifocally necrotic, and the periductular connective tissue is often mildly expanded by clear space (edema). Rarely, and with some section variation, the walls of small blood vessels are segmentally disrupted by necrotic cellular debris and brightly eosinophilic fibrillar material (fibrinoid necrosis). Aggregates of small (1-2μm) intravascular rod-shaped bacteria are also present in some sections.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Liver, necrosis, multifocal to coalescing, acute, moderate, with intracytoplasmic viral inclusion bodies and intravascular bacteria

Contributor’s Comment: Death in these chameleons is attributed to systemic ranaviral infection. Ranaviruses are increasingly recognized pathogens of fish and amphibians, which have contributed to infection, disease, and die-offs worldwide.3 As such, ranaviral infection in amphibians is reportable to the World Organization for Animal Health.12 In reptiles, ranavirus infections are well documented in turtles and tortoises, with sporadic reports in snakes and lizard species.13 While other iridoviruses have been previously isolated from chameleons7, to the author’s knowledge this is the first documented case of ranavirus-related disease in chameleons. To date, ranavirus infection of mammals and birds has not been reported.

The Ranavirus genus belongs to the family Iridoviridae, which are large viruses (120-300 nm) with double stranded DNA and an icosahedral capsid containing a lipid component.9 There are six species within the Ranavirus genus, the most well-characterized being Frog Virus 3 (FV3).5

In chelonians, ranavirus infection has been associated with sudden death, cervical / palpebral edema, and necroulcerative stomatitis / esophagitis. Histologic lesions generally include fibrinoid vasculitis, hepatic and splenic necrosis, enteritis, and pneumonia.2,6,9 Reports in snakes are rare; one report in a group of green pythons described nasal mucosal ulceration, hepatic necrosis, and necrotizing pharyngitis.4 Ranavirus has been detected in a total of 8 lizard species, with signs ranging from no overt disease to granulomatous dermatitis, necroulcerative glossitis, and hepatic necrosis.1,10,13 A recent report on ranaviral disease in lizards indicates that ranaviral infection may be an important differential diagnosis for skin lesions in lizards.13 In all hosts, subtle lesions of ranaviral infection may be obscured by secondary bacterial or fungal infection, especially when cytoplasmic inclusions are rare or inapprarent.11

The chameleons in this report presented predominately with non-specific clinical signs or sudden death. One animal presented with petechial hemorrhage and multifocal papular epidermitis progressing to vesicle formation and ulceration. The most significant microscopic findings in these cases were multifocal necrosis, most notably affecting the spleen, liver, kidney, adrenal tissues, and nasal cavity. Moderate to abundant numbers of basophilic intracytoplasmic intrahepatocytic and intrahistiocytic viral inclusions were present in the liver and nasal cavity, respectively. While stomatitis was not appreciated in this cohort, all animals exhibited varying degrees of necrotizing rhinitis with secondary bacterial and, in one animal, fungal infection. Occasional intravascular bacterial colonies were also observed in the liver of the submitted chameleon, suggestive of intercurrent bacteremia/septicemia.

Antemortem diagnostic tests for ranavirus include identification of basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions in leukocytes, PCR of blood or oral / cloacal swabs, or ELISA of plasma. Postmortem diagnostic tests include necropsy and histologic identification of basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions, virus isolation, PCR of affected tissues, and electron microscopy. Immunohistochemistry has been demonstrated in research settings, but is not available commercially10. Molecular testing for ranavirus is becoming more readily available, however many tests rely on reactivity with the highly conserved major capsid protein (MCP), which identifies the Ranavirus genus, but is not reliable for speciation. For these chameleons, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) targeting the ranavirus MCP gene was followed by sequencing of the MCP and neurofilament-like genes, which further identified the virus as a member of the Frog Virus 3 (FV3) group.

In summary, ranavirus is an emerging disease of fish, amphibians, and reptiles that exhibits high morbidity and mortality. It is becoming increasingly recognized as a pathogen of lizards and thus, should be considered a differential in lizards that present with sudden death, rhinitis, skin lesions, and splenic / hepatic necrosis.

JPC Diagnosis: Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, diffuse, severe with numerous intracytoplasmic viral inclusions, Meller’s chameleon (Trioceros melleri), reptile.

Conference Comment: The family Iridoviridae contain viruses which affect a very broad host range (arthropods, fish, amphibians, and reptiles) and produce numerous disorders to include systemic necrosis (genera Ranavirus and Megalocyticirus), and non-neoplastic skin lesions (genera Lymphocystivirus). On electron microscopy, iridoviruses form paracrystalline arrays within the cytoplasm which can be seen microscopically as prominent basophilic intracytoplasmic viral inclusions. Iridovirus virions are structurally similar to those of Asfarviridae (the causative agent of African swine fever) and functionally, as there is a limited amount of initial replication which occurs in the nucleus, followed by more extensive replication in the cytoplasm later in the disease.8

There are two known strains of ranaviruses in amphibians, ranavirus type I (Frog virus-3) and ranavirus type III (tadpole edema virus).14

Frog virus-3 (FV-3, the etiologic agent in this case), the first ranavirus identified, was originally isolated from leopard frogs infected with ranid herpesvirus-1 (Lucke’s renal adenocarcinoma). Despite the initial presumption of ranaviruses being a “benign” infectious agent, it became evident that their pathogenicity could cause a wide spectrum of diseases, ranging from cutaneous hemorrhage and necrosis to diffuse necrosis of numerous visceral organs; the aforementioned etiological agent is responsible for mass die-offs in North American frogs. Tadpoles are the most susceptible, but most wild amphibian populations are at risk of widespread epizootics. Affected tadpoles present initially with gross lesions resembling redleg, a common presentation of Gram-negative septicemia.

With ranavirus infections, the most severe lesions are in the kidneys, characterized by glomerular endothelial necrosis and hemorrhage with multifocal tubular necrosis, mild hemoglobin nephrosis, and free melanosomes within glomeruli. Additionally, there are extensive areas of hemorrhage and necrosis in the stomach and periportal to lobar necrosis in the liver. Basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies are present within glandular epithelial cells in the stomach and hepatocytes.14

Tadpole edema virus (TEV), an acute fatal infection of wild tadpoles of bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana), bufonids (Bufo americanus, Bufo woodhousei fowleri), and pelobatids (Scaphiopus intermontana) has similar gross and microscopic findings to FV-3. 14

Table 1: Viruses in the family Iridoviridae8

|

Genus |

Virus |

|

Iridovirus |

Invertebrate iridescent virus-6, 1, 2, 9, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 29, 30, 31 |

|

Chloriridovirus |

Invertebrate iridescent virus-3 |

|

Ranavirus |

Frog virus-3 (tadpole edema virus, tiger frog virus) Ambystoma tigrinum virus (regina ranavirus) Bohle iridovirus Epizootic hematopoietic necrosis virus European catfish virus (European sheatfish virus) Santee-Cooper ranavirus (largemouth bass virus, doctor fish virus, guppy virus-6) Singapore grouper iridovirus, Grouper iridovirus |

|

Megalocytivirus |

Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus |

|

Lymphocystivirus |

Lymphocystis disease virus-1 |

|

Unclassified |

White sturgeon iridovirus; Erythrocytic necrosis virus |

Conference participants debated at length regarding the presence of bacteria in vessels and sinusoids and concluded that, although ranavirus commonly occurs in conjunction with other agents, the bacteria was most likely not part of the pathogenesis and excluded it from the morphologic diagnosis.

Contributing Institution:

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Department of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology

733 N. Broadway, Suite 811

Baltimore, MD 21205

http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/mcp/

References:

- de Matos AP, Caeiro MF, Papp T, Matos BA, Correia AC, Marschang RE. New viruses from Lacerta monticola (Serra da Estrela, Portugal): further evidence for a new group of nucleo-cytoplasmic large deoxyriboviruses. Microsc Microanal. 2011;17(1):101-108.

- DeVoe R. GK, Elmore S, Rotstein D, Lewbart G, Guy J. Ranavirus-associated morbidity and mortality in a group of captive Eastern box turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina). J Zoo Wildl Med. 2004;35(4):534-543.

- Gray MJ, Chinchar VG. Introduction: history and future of Ranaviruses. In: Gray J, Chinchar, G., ed. Ranaviruses, Lethal Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates. 1st Ed.: Springer International Publishing; 2015: 1-7.

- Hyatt AD, Williamson M, Coupar B, et al. First identification of a Ranavirus from green pythons (Chondropython viridis). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2002;38(2):239-252.

- Jancovich JK, Steckler NK, Waltzek TB. Ranavirus taxonomy and phylogeny. In: Gray J, Chinchar, G., ed. Ranaviruses, Lethal Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates. 1st Ed.: Springer International Publishing; 2015: 59-70.

- Johnson AJ, Pessier AP, Wellehan JF, Childress A, Norton TM, Stedman NL, et al. Ranavirus infection of free-ranging and captive box turtles and tortoises in the United States. J Wildl Dis. 2008;44(4):851-863.

- Just F, Ahne W, Blahak S. Occurrence of an invertebrate iridescent-like virus (Iridoviridae) in reptiles. J Vet Med B. 2001;48:685-694.

- MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ. Fenner’s Veterinary Virology. 5th San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2017:182-188.

- Marschang RE. Viruses infecting reptiles. 2011;3(11):2087-2126.

- Marschang RE, Braun S, Becher P. Isolations of a Ranavirus from a gecko (Uroplatus fimbriatus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2005;45(2):295-300.

- Miller DL, Pessier AP, Hick P, Whittington RJ. Comparative pathology of Ranaviruses and diagnostic techniques. In: Gray J, Chinchar, G., ed. Ranaviruses, Lethal Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates: Springer International Publishing; 2015: 171-208.

- Schloegel LM, Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Speare R, Hill B. Two amphibian diseases, chytridiomycosis and ranaviral disease, are now globally notifiable to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE): an assessment. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2010;92(3):101-108.

- Stohr AC, Blahak S, Heckers KO, Wiechert J, Behncke H, Mathes K, et al. Ranavirus infections associated with skin lesions in lizards. Vet Res. 2013;44:

- Wright KM, Whitaker BR. Amphibian Medicine and Captive Husbandry. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company; 2001:418-420.