Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

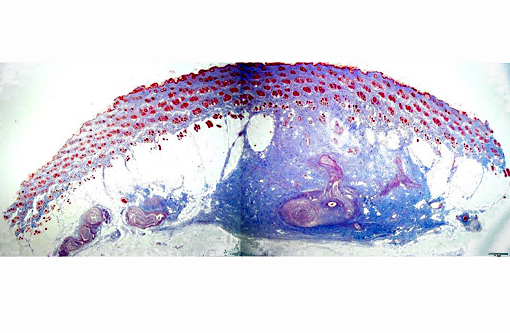

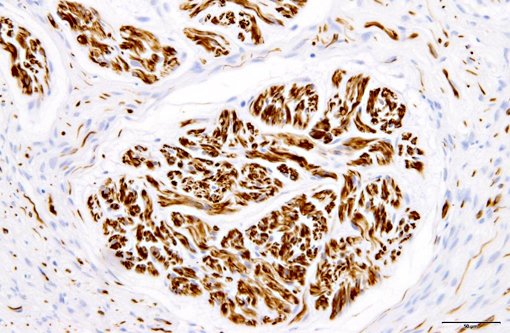

Immunohistochemically, nerve fascicles include neurofilament-positive axons with GFAP-positive Schwann cells. Hyperplastic perineurium is positive for type 4 collagen and nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR). Small nerve fibers, which are positive for GFAP and PGP9.5, are included in hyperplastic perineurium. These lesions show no significant proliferative activity based on Ki-67 staining.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Traumatic neuroma is a reactive and non-neoplastic proliferative nerve disease to injury or surgery at the proximal end of an injured peripheral nerve.(6,16) In the dog, it has been reported following tail docking.(7) Microscopically, small nerve fascicles including axons with their investiture of myelin, Schwann cells, and fibroblasts proliferate with abundant fibrous stroma.(16) Many axons were seen in a parallel distribution within fascicles.(4) Ascertaining the presence of axons by immunohistochemical examination is useful in distinguishing non-neoplastic neuroma from neoplasms such as Schwanoma and neurofibroma.(2)

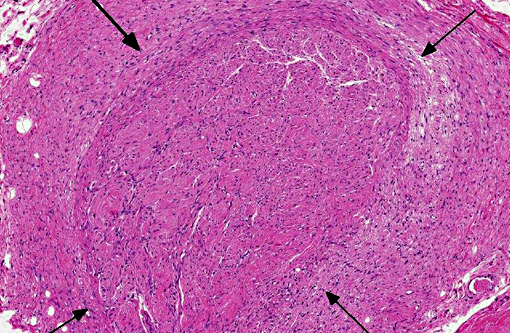

Mortons neuroma (localized interdigital neuritis) is not a true tumor and one subtype of traumatic neuroma caused by chronic or repeated mild trauma to the region. The lesion is commonly seen in the interdigital plantar nerve of third and fourth toes in women.(13,16) Histologically, proliferative changes characterize traumatic neuromas, whereas degenerative changes are the hallmark of Mortons neuroma. As the lesion progresses, the fibrosis becomes marked and envelops the epineurium and perineurium in a concentric fashion and even extends into the surrounding tissue.(8,16) Similarly, when hands are injured due to vibration from hand held power tools, demyelination and perineurial and endoneural fibrosis can develop in the nerves in fingers and wrists.(14)

The present case needs to be differentiated from a neoplasm because the histological features of hyperplastic perineurium with fibrosis are similar to Schwannoma, neurofibroma and perineurioma. Schwannoma or neurofibroma with plexiform pattern most closely resembled the present case.(13,16) With continued growth in these tumors, the fascicular components infiltrate surrounding soft tissue. The pathological features are similar to the present case at first. Schwannoma is composed of mainly Schwann cells with characteristic patterns and containing few axons. Neurofibroma consists of a mixture of Schwann cells, axons and fibroblasts, and the number of axons is very low.(13,15) Perineuroma has multiple forms: intraneural, extraneural, sclerosing, reticular, and hybrid features with neurofibroma or schwannoma.(16) Intraneural perineurioma is composed of concentric layers of perineurial cells ensheathing an axon and Schwann cell. Extraneural perineurioma is an extremely elongated spindle cell lesion arranged in parallel bundles. In the present case, perineurial cells do not proliferate inside nerve fascicles, but increase in the margin of nerve fascicles, which is a normal site. Additionally, many nerve fibers randomly proliferate in hyperplastic perineurium.

Human perineurial cells are immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), but negative for S-100.(4,11,13,16,17) GFAP and S100 commonly stain Schwann cells. Thus, immunostaining for these proteins is always used to distinguish between perineurial cell and Schwann cells. However, in canine perineurioma, the tumor cells are negative for EMA.(10) The basement membrane between perineurial cells are positive for type 4 collagen and laminin.(16) Additionally, positive staining for type 4 collagen and NGFR can help identify nerve origin.(3,4) Thus, our results indicate that immunohistochemistry for type 4 collagen and NGFR might be useful for identifying perineurial cells of the dog.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Neuroma development following trauma, most commonly observed subsequently to tail-docking or digital neurectomy in horses, is presumed to arise when the normal regenerative growth of a disrupted nerve fiber encounters a physical obstruction such as scar tissue.(7) This results in a haphazard arrangement of axons and disorganized microfascicular architecture, observed in this case as numerous Schwann cells and few axons haphazardly arranged and surrounded by a variably thick fibrotic perineurium.

The classification of a non-neoplastic lesion implies the proliferating cell population still possesses control over its growth cycle and/or stability of its genome. This is an opportunity for the reader to review the hallmarks of neoplasia and independently consider whether any of these may apply in this case. The following six hallmarks are acquired in succession and lead to cells becoming neoplastic and eventually malignant: sustained proliferative signaling, evasion of growth suppressors, resisting cell death, enabling replicative immortality, induction of angiogenesis and the activation of invasion and/or metastasis. Recently, two further hallmarks have been added: the reprogramming of energy metabolism and evasion of the immune response. Two characteristics described as crucial to the acquisition of these hallmarks are genomic instability and tumor-promoting inflammation. When mutations are permanently acquired in the genome, the cell may develop a selective advantage that enables its outgrowth and eventual dominance in the local environment that may be fueled by growth and survival factors supplied by secondary inflammatory cells.(9)

Conference participants reviewed the most common neural tumors of domestic animals. Schwannomas, which originate from a single nerve and extend in conjunction with but external to it, facilitates its involvement with plexus arrangements such as the brachial plexus and other common sites including the heart base, spinal nerve roots and the tongue.(12) Neurofibromatosis is a well-recognized variant of Schwannomas observed in cattle in which multiple sites are involved. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors are of controversial origin, but often found on the distal limbs of dogs and graded according to soft tissue sarcoma criteria.(5) Ganglioneuromas are rare tumors reported in many species and are composed of ganglion and glial cells. Ganglioneuroblastomas are similar but are composed of poorly differentiated ganglion cells with more atypic.(12)

References:

1. Antunes SL, Chimelli L, Jardim MR, et al. Histopathological examination of nerve samples from pure neural leprosy patients: Obtaining maximum information to improve diagnostic efficiency. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(2):246-253.

2. Arishima H, Takeuchi H, Tsunetoshi K, Kodera T, Kitai R, Kikuta K. Intraoperative and pathological findings of intramedullary amputation neuroma associated with spinal ependymoma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2013;30:196-200.

3. Chijiwa K, Uchida K, Tateyama S. Immunohistochemical evaluation of canine peripheral nerve sheath tumors and other soft tissue sarcomas. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:307-318.

4. Chrysomali E, Papanicolaou SI, Dekker NP, Regezi JA. Benign neural tumors of the oral cavity: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:381-390.

5. Dennis MM, McSporran KD, Bacon NJ, Schulman FY, Foster RA, Powers BE. Prognostic factors for cutaneous and subcutaneous soft tissue sarcomas in dogs. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):73-84.

6. Ginn PE, Mansell JL, Rakich PM. Neoplastic and reactive disease of the skin and mammary glands. In: Jubb & Kennedy Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. St Louis, MO: Sanders Elserver; 2006:761-767.

7. Gross TL, Carr SH. Amputation neuroma of docked tails in dogs. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:61-62.

8. Guiloff RJ, Scadding JW, Klenerman L. Morton's metatarsalgia. Clinical, electrophysiological and histological observations. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:586-591.

9. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674.

10. Higgins RJ, Dickinson PJ, Jimenez DF, Bollen AW, Lecouteur RA. Canine intraneural perineurioma. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:50-54.

11. Hirose T, Tani T, Shimada T, Ishizawa K, Shimada S, Sano T. Immunohistochemical demonstration of EMA/Glut1-positive perineurial cells and CD34-positive fibroblastic cells in peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:293-298.

12. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Jubb & Kennedy Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1. St Louis, MO: Sanders Elsevier; 2006:455.

13. Rosai J. Tumors and tumor-like conditions of periperal nerves. In: Rosai and Ackerman's Surgical Pathology. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2004:2263-2271.

14. Stromberg T, Dahlin LB, Brun A, Lundborg G. Structural nerve changes at wrist level in workers exposed to vibration. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:307-311.

15. Swanson HH. Traumatic neuromas: a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1961;14:317-326.

16. Weiss SW, Goldblum GJ. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2013:784-854.

17. Yamaguchi U, Hasegawa T, Hirose T, et al. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathological study of five cases and diagnostic utility of immunohistochemical staining for GLUT1. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:159-163.