WSC 22-23

Conference 14

Case IV:

Signalment:

An adult, male castrated, Golden Retriever, Canis lupus familiaris, dog.

History:

The dog presented with reluctance to move and severe pain localized in the cervical spine. Proprioception was decreased in all four legs. MRI showed lytic changes in C2, C7 and T2 vertebral bodies with extension to adjacent musculature and compression of corresponding spinal cord segments. A neoplastic process was suspected and the dog was euthanized due to poor prognosis.

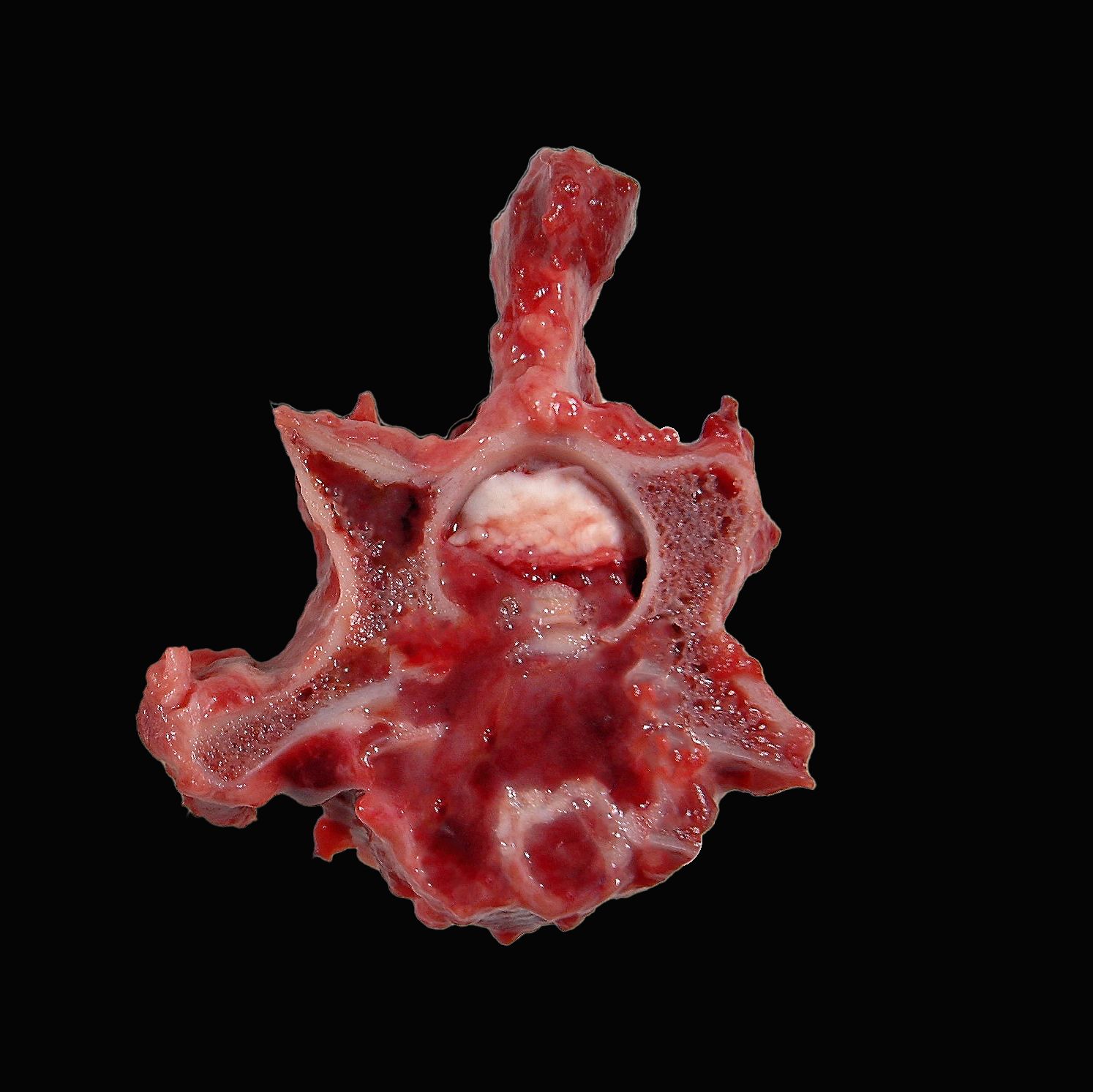

Gross Pathology:

Extending from C2 to T2, the bone marrow of the vertebral bodies, and less frequently the lamina and transverse processes, was gelatinous, dark red to grey-tan and porous with complete effacement of the trabecular bone. Frequently, the process destroyed the cortical bone infiltrating the epaxial and hypaxial muscles and/or protruding into the spinal canal compressing the spinal cord and nerve roots.

Laboratory Results:

Complete blood count revealed mild anemia and serum biochemistry was unremarkable.

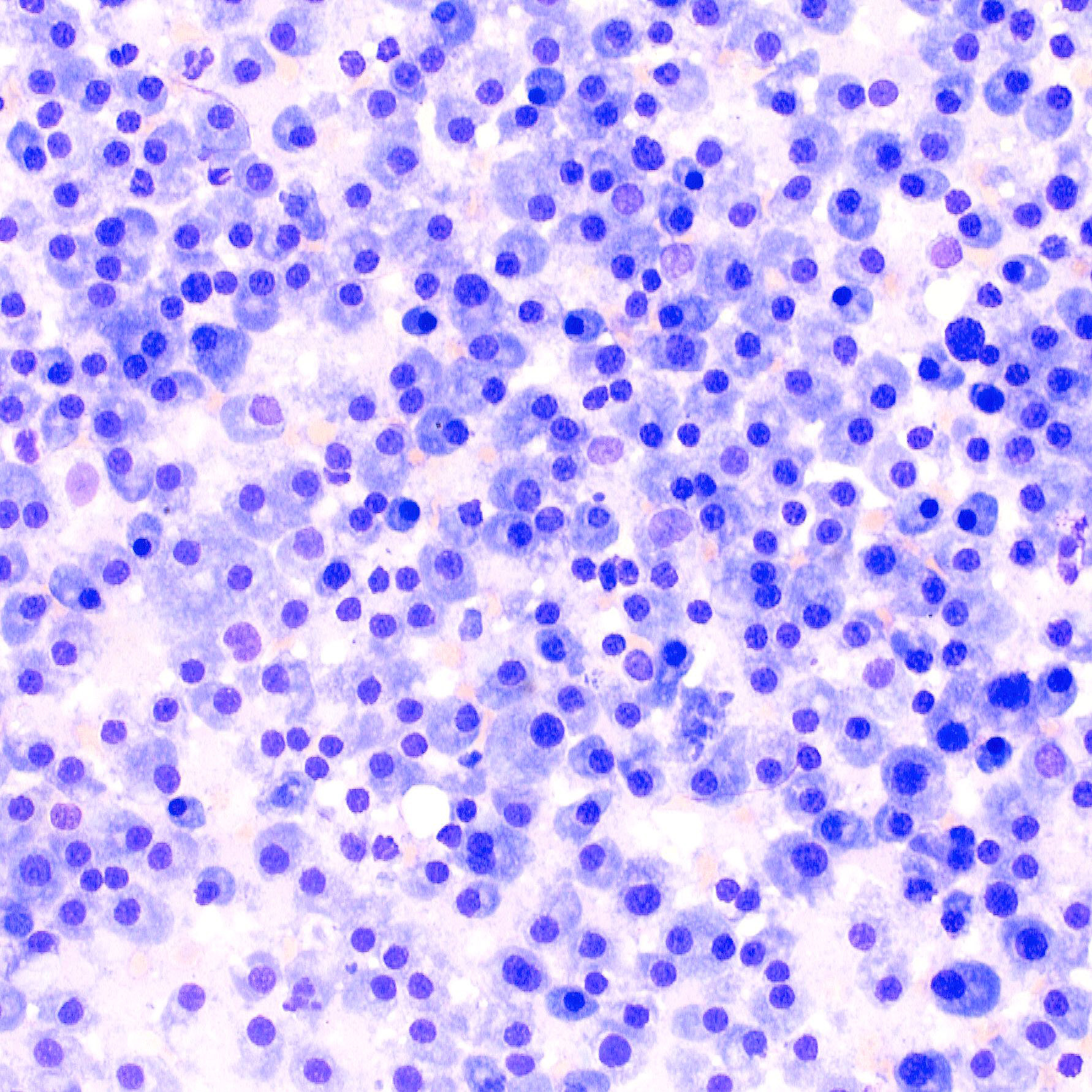

Cytologic smear from affected bone marrow of T2: The cytologic smear consists primarily of round cells (neoplastic plasma cells) with moderate amounts of basophilic cytoplasm, round eccentric nuclei and perinuclear white halo. Neoplastic plasma cells show mild to moderate anisokaryosis and anisocytosis and are occasionally binucleated. Mitoses are rare.

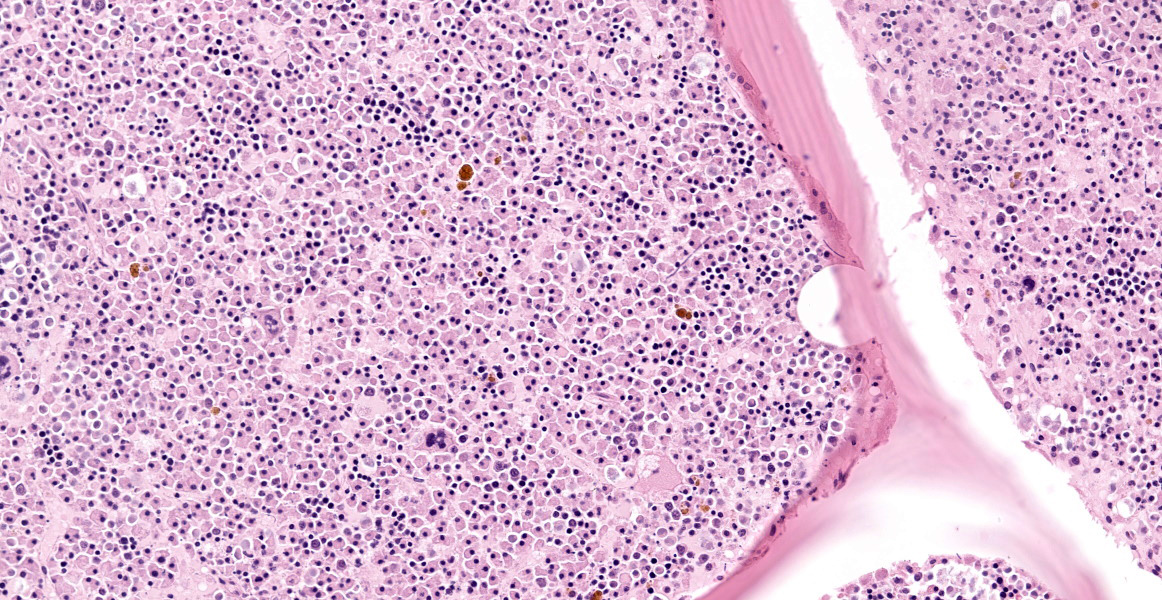

Microscopic Description:

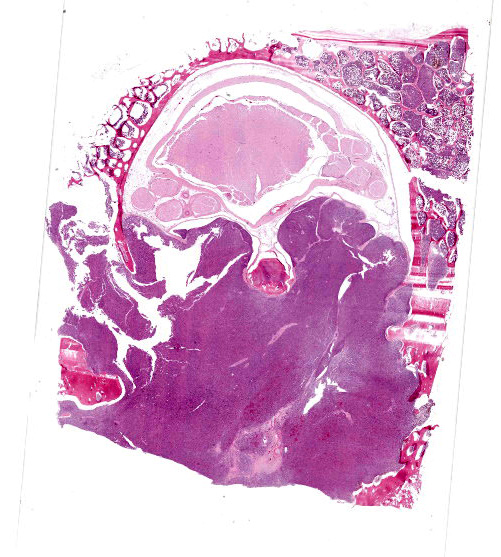

Vertebra (T2) and corresponding spinal canal and spinal cord:

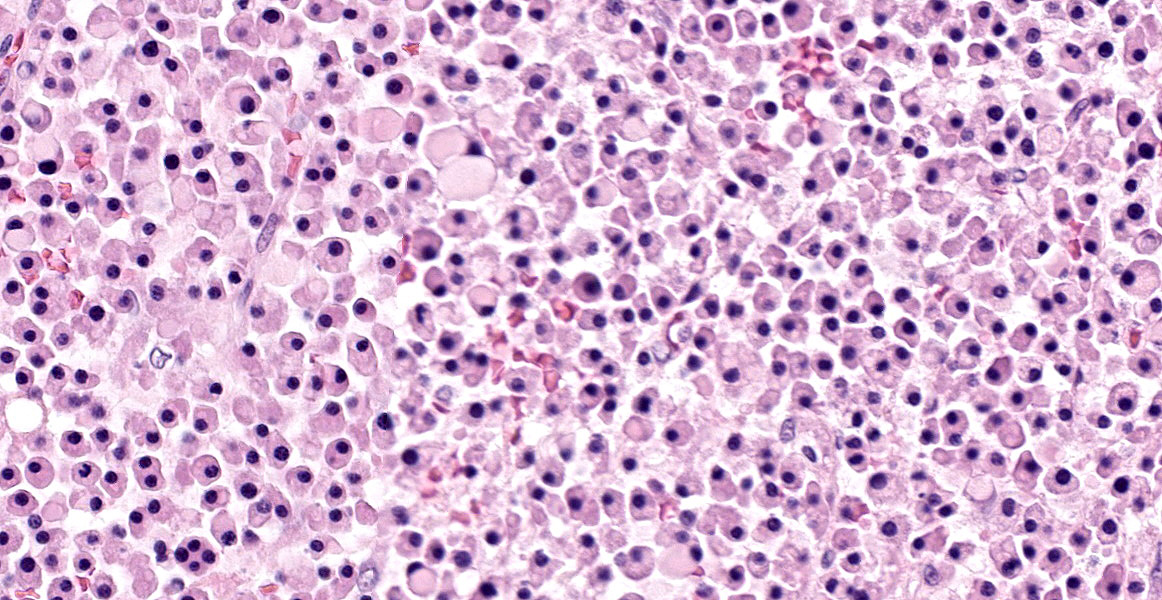

Up to 70% of the medullary cavity is effaced by an unencapsulated, poorly demarcated, infiltrative and densely cellular neoplastic process composed of round cells arranged in sheets laying on small amounts of pre-existing fibrovascular stroma. Neoplastic cells have distinct cell borders, moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm with occasional perinuclear white halo, round to oval, hyperchromatic, eccentric nuclei with up to one basophilic nucleoli. Some cells show large intracytoplasmic pale eosinophilic, homogenous vacuoles pushing the nucleus to the periphery and there are occasional binucleated cells. Mitoses are up to 2 per HPF. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild to moderate. Necrotic foci composed of eosinophilic cellular debris and karyorrhectic/pyknotic nuclei are observed multifocally. Up to 60 % of trabecular and cortical bone are lytic and/or necrotic and replaced by dense sheets of neoplastic cells and hemorrhages.

Spinal cord (T2): Multifocally, affecting the white matter of the lateral and ventral funiculi, small numbers of axons show evidence of axonal degeneration characterized by dilated myelin sheaths containing glassy, eosinophilic, swollen axons (spheroids) accompanied by increased numbers of activated astrocytes with enlarged, vesicular nucleus (astrocytosis), few astrocytes with large amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nucleus (gemistocytes) and activated microglia.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Vertebra (T2): Multiple myeloma with osteolysis and infiltration towards the spinal canal

Spinal cord, T2, white matter: axonal degeneration (ventrolateral funiculi), multifocal, mild, with dilated myelin sheaths and spheroids

Contributor’s Comment:

This case represents a classical case of multiple myeloma (MM) affecting the cervical and thoracic vertebrae with multicentric osteolysis and extension towards the spinal canal. MM is a malignant tumor originating from clonal proliferation of plasma cells within the bone marrow. In domestic animals, MM is most commonly reported in dogs, less frequently in cats and occasionally in horses. In dogs, it accounts for approximately 0,5 % of all malignant tumors.2,11 It is usually diagnosed in middle-aged to old dogs and rarely affects young individuals.2,11,12 The predilection sites include the vertebrae, ribs, femur, humerus and pelvis, all of which have active hematopoiesis.2,10,11 The clinical signs are unspecific unless there is tumor-associated bone fracture and spinal cord or nerve roots compression. Generally, affected dogs present with lethargy, weight loss, anorexia, vomiting and fever.7

The diagnosis of MM in dogs follows the criteria used for human MM, which is based on detecting ≥2 features including 1) bone marrow with >5 % or >20% of neoplastic plasma cells, 2) lytic bone lesions, 3) presence of clonal immune-globulin paraproteins in the serum (monoclonal gammopathy) and 4) presence of free light-chain immunoglobulins (fLC) in urine (Bence-Jones proteinuria).5,7,12 Additional clinical findings can include anemia, hyperviscocity syndrome, bleeding disorders and hypercalcemia.11 Increased numbers of plasma cells in the bone marrow can be also a feature of infectious diseases including ehrlichiosis and leishmaniasis, which should be taken into consideration if other features of MM are not evidenced.11

Gross findings in the affected bone are characterized by discrete, irregular, soft to gelatinous, pink-grey foci of tumor tissue replacing trabecular and cortical bone. Secondary pathological fractures may be evidenced.2,11

Histologically MM is characterized by dense colonies of well differentiated, monoclonal plasma cells or large, anaplastic plasma cells with high mitotic index, which replace normal hematopoietic and adipose tissue. Multiple myeloma oncogene 1/interferon regulatory factor 4 (MUM1/IRF-4) immunohistochemistry can be used for confirmation of plasma cell tumors in dogs and cats, but is often unnecessary due to distinctive histological features of MM.2,11 Infiltration to the bone with osteolysis is a typical finding mediated by cytokines produced by neoplastic plasma cells leading to decreased numbers of osteoblasts, suppression of their activity and increased numbers of activated osteoclasts. The excess of osteoclastic activity will cause destruction of bone tissue.1,11

Metastasis to visceral organs is rarely reported in dogs with the spleen being the most common site. This feature differs from MM in cats, in which metastasis to abdominal organs including spleen, liver, and lymph nodes is frequently observed.4,6,11 Overall, MM can be additionally accompanied by renal disease or amyloidosis, since light-chain immunoglobulins produced by the neoplastic plasma cells can be deposited in the glomerular membrane resulting in glomerulonephritis, or form amyloid to be deposited in the glomeruli, spleen or liver.3,4,11 In this case, histological changes observed in the adjacent spinal cord including dilation of the myelin sheaths and spheroid formation are secondary to compression caused by the tumor mass protruding into the spinal canal.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Biosciences

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine

University of Helsinki

https://www.helsinki.fi/en/faculty-veterinary-medicine/research/veterinary-biosciences

JPC Diagnosis:

Vertebra and spinal canal: Myeloma.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of this classic condition seen in both human and veterinary medicine. All veterinarians and veterinary pathologists are familiar with the condition Bence Jones proteinuria and its neoplastic cause; fewer have knowledge of Dr. Henry Bence Jones and his initial characterization of the phenomenon which bears his name. Dr. Bence Jones was a British physician of the mid-19th century whose initial research focused on chemical chemistry, specifically the analysis of cysteine oxide stones and proteins. He later specialized in the composition of urine in health and disease. Thomas Alexander McBean was a patient afflicted by bone pain and peripheral edema (and who is now known to have suffered from multiple myeloma). His urine contained a protein that produced peculiar results when analyzed using standard laboratory testing at the time. The patient’s attending physicians sent a sample to Dr. Bence Jones. After further testing, he dubbed the protein “hydrated deutoxide of albumin” and published the first reports on this unique urinary protein. Bence Jones proteins are now considered to be the first tumor marker discovered, and Dr. Bence Jones the first chemical pathologist.8

A recent report described a case of erythrophagocytic multiple myeloma, which is incredibly rare in dogs and cats and slightly more common in humans.7 A 5 year old female spayed golden retriever dog presented for a severe nonregenerative anemia and thrombocytopenia, and abundant neoplastic plasma cells which occasionally exhibited erythrophagocytosis were observed in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow.7 Anemia in the patient was likely due to erythrophagia; however, dogs with multiple myeloma commonly have anemia due to erythrocyte destruction in hyperviscosity syndrome, myelophthisis, blood loss, or anemia of chronic disease, so these may have also contributed to the anemia.7 This week’s moderator also explain that anemia is a common presenting complaint in human patients with multiple myeloma.

References:

- Brigle K, Rogers B. Pathobiology and Diagnosis of Multiple Myeloma. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33(3).

- Craig LE, Dittmer KE., Thompson KG. Bones and joints. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:123.

- Kim DY, Taylor HW, Eades SC, Cho DY. Systemic AL amyloidosis associated with multiple myeloma in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2005;42(1).

- Mellor PJ, Haugland S, Smith KC, et al. Histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and cytologic analysis of feline myeloma-related disorders: Further evidence for primary extramedullary development in the cat. Vet Pathol. 2008;45(2).

- Moore AR, Harris A, Jeffries C, Avery PR, Vickery K. Retrospective evaluation of the use of the International Myeloma Working Group response criteria in dogs with secretory multiple myeloma. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35(1).

- Patel RT, Caceres A, French AF, McManus PM. Multiple myeloma in 16 cats: A retrospective study. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34(4).

- Romanelli P, Recordati C, Rigamonti P, Bertazzolo W. Erythrophagocytic multiple myeloma in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. Published online May 21, 2022. doi:10.1177/10406387221092299

- Sewpersad S, Pillay TS. Historical perspectives in clinical pathology: Bence Jones protein – early urine chemistry and the impact on modern day diagnostics. J Clin Pathol. 2020; 0:1-4.

- Sung S, Lim S, Oh H, Kim K, Choi Y, Lee K. Atypical radiographic features of multiple myeloma in a dog: A case report. Vet Med. 2017;62(9).

- Thompson KG, Dittmer KE. Tumors of bone. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in domestic animals. 5th ed. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons; 2017:412,513.

- Wachowiak IJ, Moore AR, Avery A, et al. Atypical multiple myeloma in 3 young dogs. Vet Pathol. Published online April 11, 2022. doi:10.1177/03009858221087637