Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 4

Sept 19th, 2018

CASE I: N14-111 (JPC 4049562-00).

Signalment: Three-year-old castrated male, Scottish terrier cross canine

History: Presented with a history of renal failure and protein-losing nephropathy

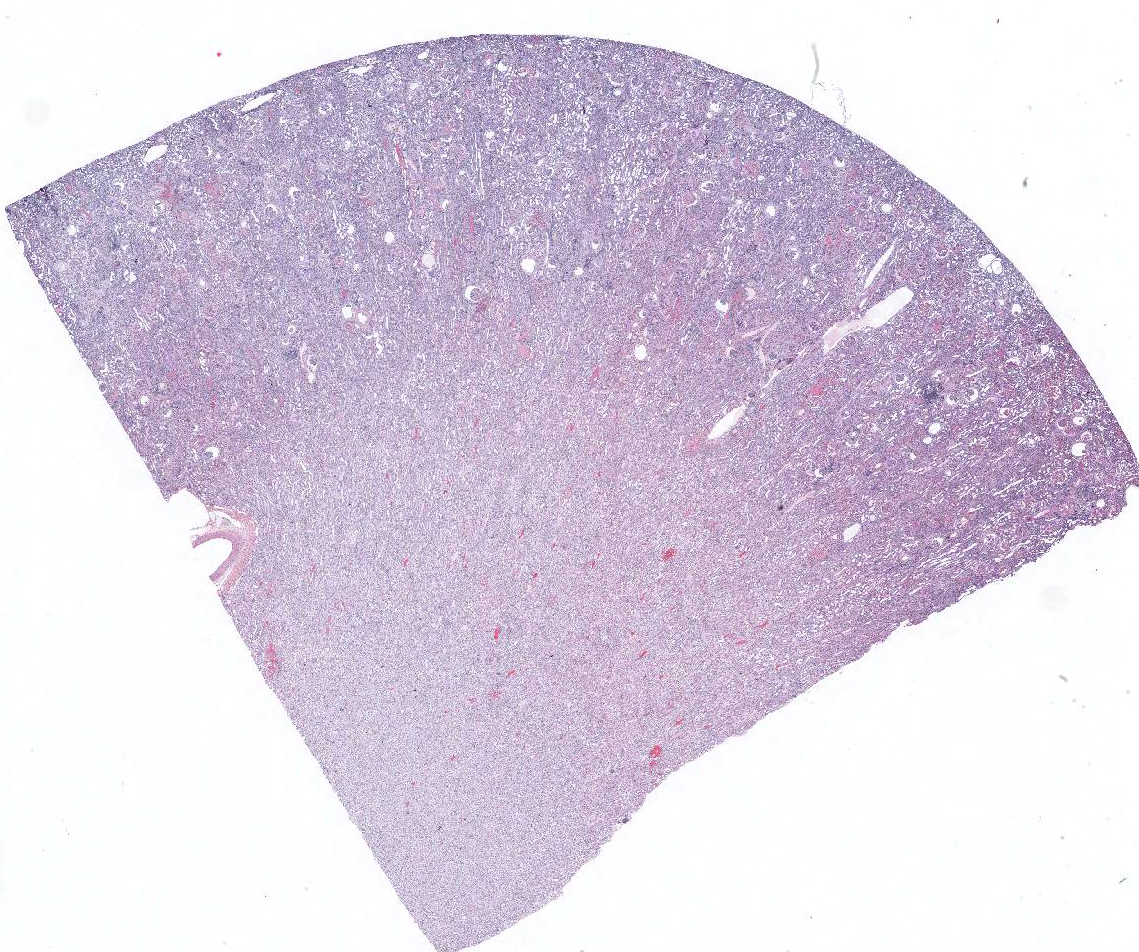

Gross Pathology: Enlarged pale kidneys with dozens of red pinpoint foci in the cortex.

Laboratory results: None.

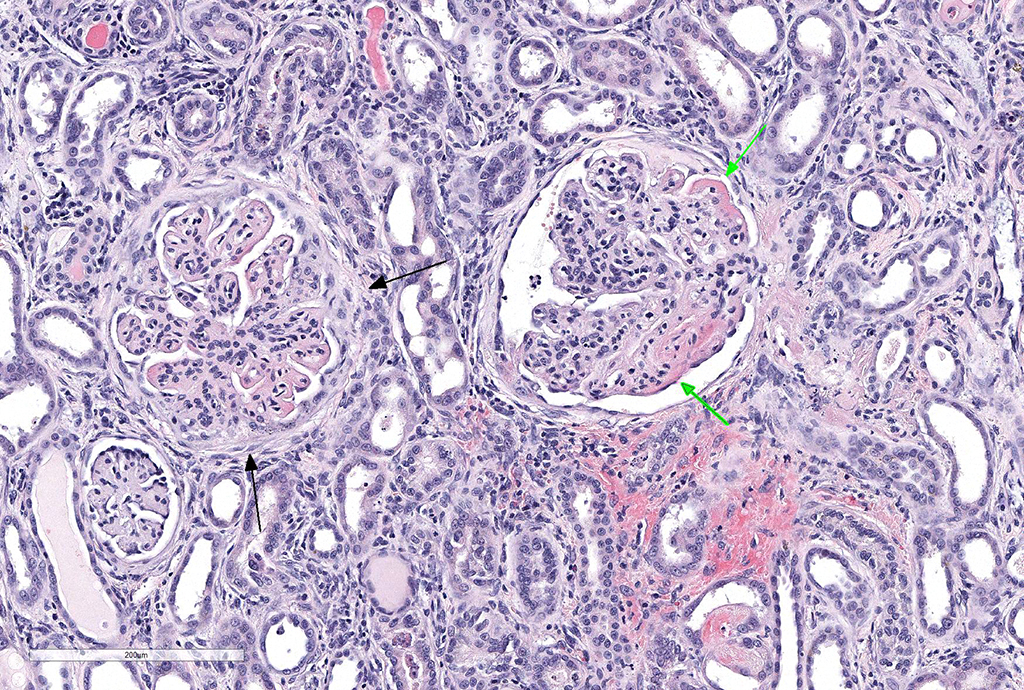

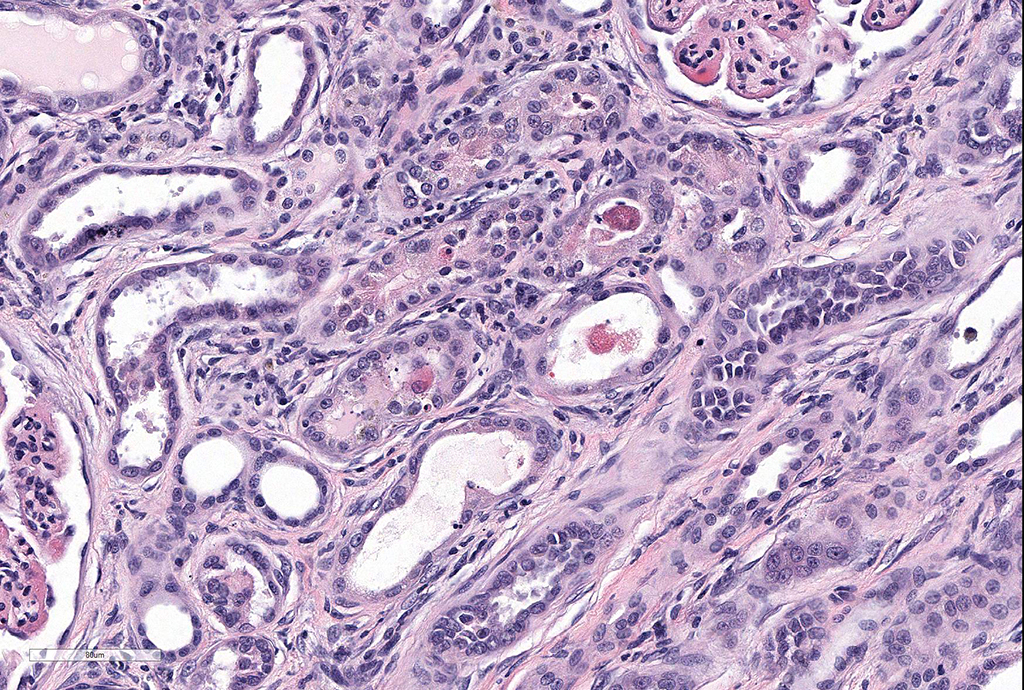

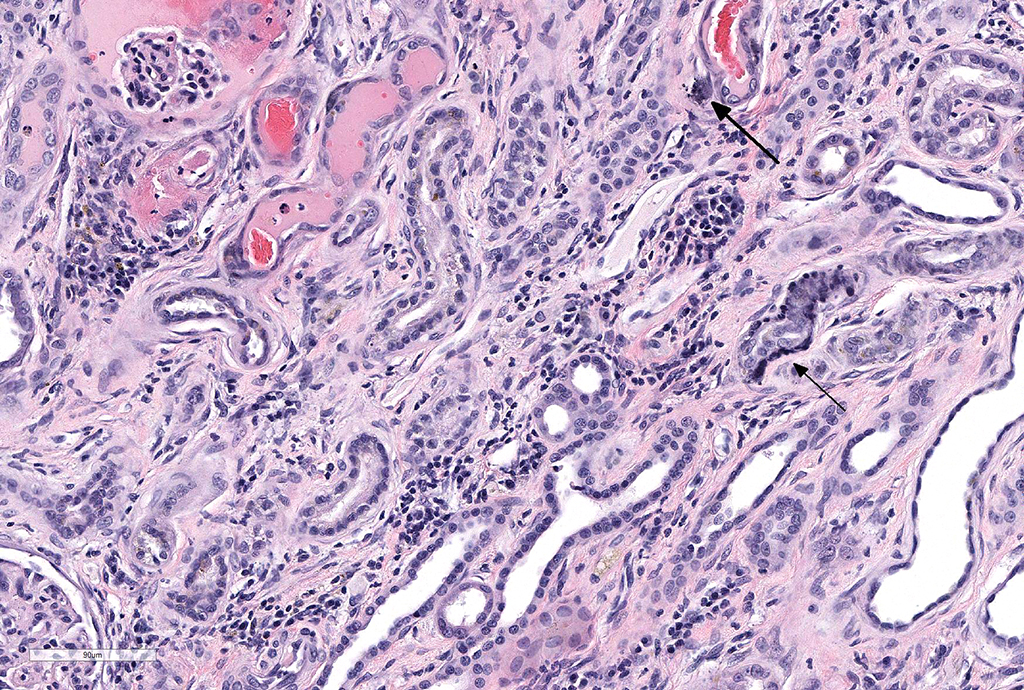

Microscopic Description: Kidney: Diffusely, glomeruli fill Bowman’s space and are segmented. They are globally hypercellular with markedly increased mesangial matrix, typically with obliteration of capillary lumina. Synechiae are present multifocally. Tufts occasionally contain karyorrhectic debris, intravascular or intramesangial leukocytes, or exhibit exudation of fibrin and/or proteinaceous fluid into Bowman’s space. Podocytes and parietal epithelial cells are frequently hypertrophied. There is multifocal, mild to moderate periglomerular fibrosis. Diffusely, tubules vary from dilated and lined by attenuated to regenerating epithelium to lined by swollen, vacuolated epithelial cells undergoing hydropic degeneration and necrosis with cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia, nuclear pyknosis, and cellular sloughing. Many tubules contain proteinaceous fluid or casts with fewer containing cellular casts. Occasional tubules are mineralized. The interstitium multifocally contains moderate numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells with mild interstitial fibrosis. Rare arterioles exhibit fibrinoid necrosis and are surrounded by hemorrhage and fibrin (too infrequent to be a point in these slides).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses: 1. Marked, diffuse, global, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with moderate tubular proteinosis

- Moderate, multifocal, lymphoplasmacytic, interstitial nephritis

- Moderate, multifocal, tubular necrosis, degeneration, and regeneration

Contributor’s Comment: Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi is one of the most common tick-borne diseases in the world. The organism is a spirochete, is transmitted by Ixodes ticks and lives extracellularly near collagen and fibroblasts usually causing little inflammation in most hosts. Lyme nephritis, which is the most serious form of Lyme disease in dogs is incompletely understood, as recent evidence has shown that there is no consistent evidence of the presence of B. burgdorferi in the renal tissue of dogs with Lyme nephritis. Koch’s postulates have not been satisfied and there is no experimental model to study the disease.

As compared with cases of arthritis, fewer dogs (<1-2%) with Lyme-positive status develop severe acute progressive and often fatal protein-losing nephropathy. Labradors, Golden Retrievers and younger dogs are predisposed. Unlike leptospirosis, Lyme nephritis is not due to renal invasion by the spirochete but rather due to immune-mediated glomerulonephritis with Lyme-specific antigen-antibody deposition.5,7 The microscopic findings of the kidney from Lyme-positive dogs with severe proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and kidney failure exhibit membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis with subendothelial C3, IgG and IgM deposits, diffuse tubular necrosis/regeneration and lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis.3 The breed predisposition, younger age of onset and histopathologic findings are different when compared to previously described types of glomerulonephritis. It is thought that the secondary tubular changes may be due to hypertension and efferent arteriole vasoconstriction, tubular hypoxia or toxic proteins in the glomerular filtrate. Very few if any organisms are found by silver stain or PCR in kidneys of dogs with Lyme nephritis. However, Lyme antigen, DNA and occasionally organisms have been found in tubular cells and in urine.5,7

JPC Diagnosis: Kidney: Glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative, diffuse and global, severe, with synechia and crescent formation, tubular epithelial necrosis, thrombotic microangiopathy of vascular poles, and moderate lymphoplasmacytic interstitial nephritis.

Conference Comment: The contributor provides a concise summary of much as is known about the renal effects of Lyme borreliosis in dogs. Retrievers are predisposed but many breeds are affected in endemic areas.2 Renal disease has been reported to occur in less than 2% of dogs of serologically positive for Lyme disease; approximately 30% of patients with Lyme disease had concurrent or prior lameness.2 Antigen-antibody complexes against bacterial outer surface proteins (OSP) OspA, OSpB, and flagellin are thought to be causative for glomerular disease.2

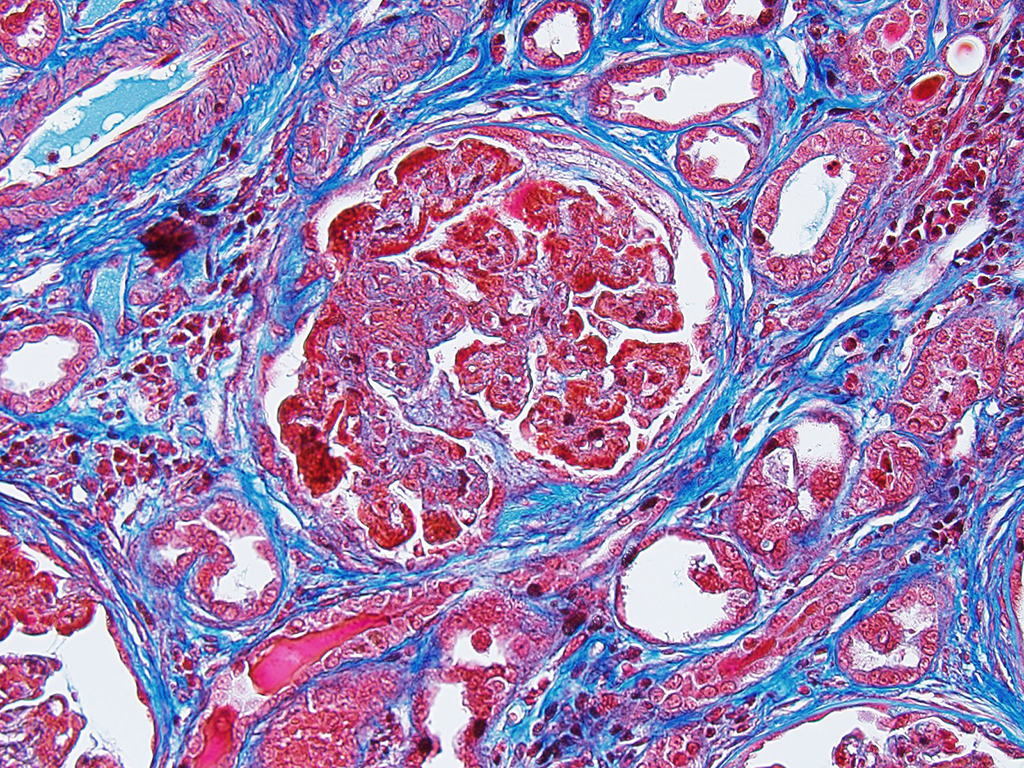

Lyme disease and other chronic infectious agents most often result in membranoproliferative patterns of glomerulonephritis (MPGN) in the dog. From the recent online atlas published by the moderator and other members of the WSAVA study group on renal standardization (https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/vetrenalpathatlas/chapter/membranoproliferative-glomerulonephritis/): “…In the MPGN pattern, lesion progression is not straightforward. The lesions are dependent on the duration/magnitude of immune complex deposition and the severity of the resultant inflammatory response (inflammatory cells and inflammatory mediators). Features that should be assessed include: a) Hypercellularity – this dimension involves the number, location, and types of cells that are present in the glomeruli in excess of what is expected in normal glomeruli, as well as evidence of cellular injury (e.g., pyknotic debris); b) capillary wall remodeling – this dimension invoves the degree and extensiveness of changes in the structures that compose the peripheral capillary wall; namely wall thickening, doule contours of the GBM, cellular interpositioning; and c) sclerosis – this dimension involves the degree and extent of changes that are thought to be irreversible, namely synechia and segmental or global sclerosis.”1

Equine borreliosis due to B. burgdorferi is an emerging disease in many parts of the world. The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine has recently published a consensus statement about B. burgdorferi infection in horses in North America.4 Documented syndromes in the horse attributed to B. burgdorferi infection include neuroborreliosis, uveitis, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.4 Although other cases exhibiting lameness and stiffness have been identified in horses, these are often not well documented. Diagnosis of Lyme disease in the horse requires cytology or histopathology of infected fluid or tissue as well as antigen detection.4

Neuroborreliosis in horses parallels a similar syndrome in humans which generally results in a triad of meningitis, cranial or peripheral neuritis and radiculitis; while clinical signs may be extremely variable, the histologic lesions seen in the horse are unique in equine neuropathology.4 Gross lesions are limited to meninges and include opacification, yellowish discoloration, and plaques of hyperemia and edema.6 Microscopically, horses display variable infiltration of the leptomeninges as well as perivasculitis and segmental vasculitis.6 Lymphohistiocytic infiltrates predominate but neutrophilic, eosinophilic, and plasmacytic inflammation is also seen inflammatory cells may infiltrate cranial nerves and ganglia resulting in Wallerian degeneration and spheroid formation.6 Five reports of equine uveitis are present in the veterinary literature.4 Of these, 3/5 infected horses also displayed neurologic signs and neural inflammation.4 Organisms were detected within the leptomeninges and vitreous of the eye through the use of Warthin-Starry stains as well as PCR performed on shavings from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections.4

Cutaneous pseudolymphoma is a rare condition associated with B. burgdorferi infection in the horse, but has also been replicated in experimentally infected colonies.4 Papular to nodular lesions occurring most often at the site of the tick bite and florid mixed lymphoid hyperplasia are microscopically suggestive of lymphoma in these cases. PCR performed on these lesions will be positive for B. burgdorferi.4

The moderator discussed a number of potential ruleouts for immune-complex glomerulonephritis in the dog, including Dirofilaria immitis infection (which does not always present as a MPGN), tick-borne diseases, The glomerular lesions seen with leishmaniasis are similar to that seen in this case. The moderator identified the widespread single cell necrosis in occurring in many tubules as a prominent feature in this particular condition, but also suggested that tubulointerstitial nephritis is not particularly specific for Lyme disease (as has been previously published) and many cases of very active MPGN may result in tubular necrosis resulting from concurrent simultaneous deposition of immune complexes in peritubular capillaries.

The moderator identified the hypercellularity in the glomeruli as being both endocapillary and in the mesangium. A Masson’s trichrome run at the JPC on this case highlighted large bright red, often coalescing immune complexes within the subendothelial locations. (“Wire loops” is a term used in human medicine for the appearance of thickened capillary wall due to large coalescing immune complexes.)

The moderator also discussed the changes noted in approximately 20% of the vascular poles, which often display necrosis and intramural protein and erythrocytes (suggestive of possible concurrent hypertension in this patient.) As well as the two potential ways that crescents can form – from rupture of glomerular capillaries or less commonly, due to the rupture of Bowman’s capsule.

Contributing Institution:

Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Biomedical Sciences

200 Westboro Road

North Grafton

MA 01536

References:

- Cianciolo R, Brown CM, Mohr C, Mabity M, Van der Lugt J, McLeland S, Aresu L, Benali S, Spangler B, Amerman H, Lees G. In Atlas of Renal Lesions in Proteinuric Dogs. https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/vetrenalpathatlas/chapter/membranoproliferative-glomerulonephritis/

- Cianciolo RE and Mohr FC. Urinary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th 2016; St. Louis MO, Elsevier Press, vol 2, p. 411-412.

- Dambach DM, Smith CA, Lewis RM, Van Winkle TJ. Morphologic, Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural characterization of a distinctive renal lesion in dogs putatively associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection: 49 Cases (1987-1992). Vet Pathol. 1997; 34:85-96

- Divers TJ, Gardner RB, Madigan JE, Witonsky SG, Bertone JJ, Swinebroad EL, Schutzer SE, Johnson. Borrelia burgdorferi infection and Lyme disease in North American Horses: A consensus statement. Vet Intern Med 2018:617-683.

- Hutton TA, Goldstein RE, Njaa BL, Atwater DZ, Chang YF, Simpson KW. Search for Borrelia burgdorferi in kidneys of dogs with suspected “Lyme Nephritis”. J Vet Intern Med. 2008; 22(4):860-5

- Johnston LK, Engiles, JB, Aceto H, Bucchner-Maxwell V, Divers T, Gardiner R%, Levine, R, Shceere N, Tewai D, Tomlinson J Johnson AL. Retrospective evaluation of horses diagnosed with neuroborreliosis on postmortem examination: 16 cases (2004–2015). J Vet Intern Med 2016; 30:1305-1312.

- Littman MP. Lyme nephritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2013; 23(2):163-73