Signalment:

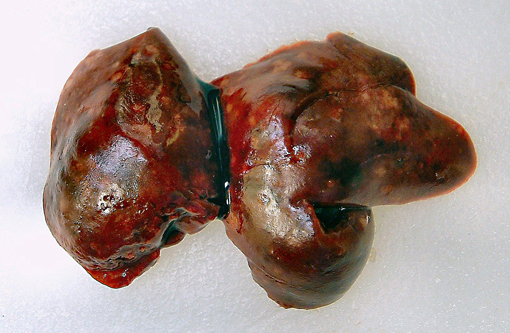

Gross Description:

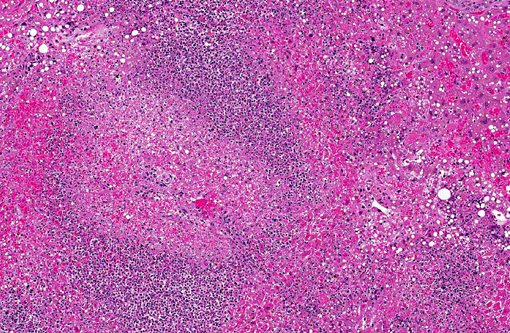

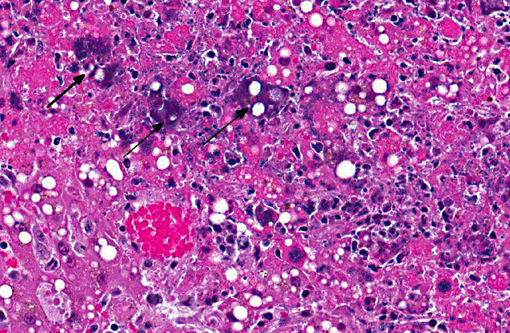

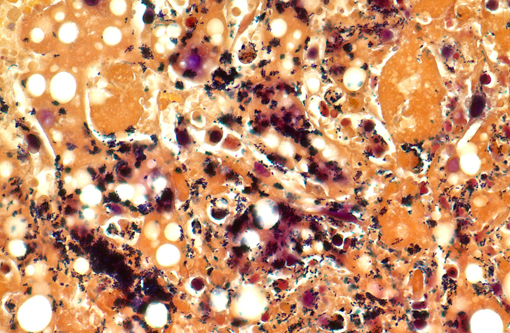

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Most incidents of listeriosis occur when the host ingests contaminated soil, water or food.(1,2,5,6,7) The bacterium is internalized into the host cell using the surface protein internalin, which interacts with E-cadherin on the host cells allowing the bacterium to cross the intestine, placenta, and blood-brain barrier.(1,2,5,7,9) Once inside the host cell, the bacterium lyse the phagocytic cell phagolysosome using a pore-forming protein called listeriolysin O and two phospholipases allowing it to gain access to the host cell cytoplasm. The bacterium then replicates within the host cell cytoplasm. Listeria has the ability to co-opt the host cell actin filaments using the bacterial surface protein ActA to help it migrate to the host cell membrane to induce pseudopod-like protrusions that can be transferred to another host cell. The host protection against Listeria appears to be mediated by IFN-γ production by NK cells and T-lymphocytes as host macrophages stimulated by IFN-γ phagocytose and kill Listeria while host macrophages that internalize Listeria coated by C3 become infected.(1)

Severe disease caused by Listeria monocytogenes tends to manifest as three distinct syndromes in both animals and humans: abortion after infection of the pregnant uterus, septicemia with visceral abscesses, and meningoencephalitis.(1,2,9) The syndromes, particularly the neurologic and genital forms of listeriosis, rarely occur at the same time.(2) Abortions occur most commonly in cattle and sheep, but have also been reported in women and other species.(1,2) Encephalitic listeriosis occurs most commonly in ruminants while people tend to develop suppurative meningitis.(1,2) All species seem to be susceptible to septicemia with Listeria.(5)

In abortions, Listeria crosses the placenta and most likely results in fetal septicemia.(6) The gross lesions in the fetus often include severe placentitis and multiple pinpoint yellow foci in multiple organs, which are most prominent in the liver. However, the gross fetal visceral lesions are easily obscured by postmortem decomposition. The microscopic lesions in the fetal organs consist of foci of necrosis filled with degenerate neutrophils and macrophages surrounded by bacteria. Necrotizing enterocolitis with intralesional bacteria may be present. Meningitis can also be seen in the fetus. The microscopic placental lesions include necrosis of the cotyledonary villi with a suppurative exudate and many bacteria.

The neurologic form of listeriosis in ruminants is most often the result of feeding contaminated silage.(2,5,7,9) The bacteria travel via the trigeminal nerve and other sensory nerves to the brainstem possibly gaining entry to the nerves through wounds in the oral cavity. There usually are no gross lesions associated with neurologic listeriosis in ruminants. The microscopic lesions are limited to the brainstem. The microscopic lesions can range from small early lesions of accumulations of glial cells to severe encephalitis with macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and the formation of the characteristic microabscesses. Bacteria can be seen in some lesions.

The septicemic form of listeriosis most often occurs in neonates and young animals, but can occur in adult animals.(1,2,8,9) The gross and microscopic lesions consist of multifocal necrosis and microabscesses that can contain bacteria.(2) These lesions occur most frequently in the liver. Although the source of the bacterium is often not identified in septicemic cases, potential sources include contamination of the pregnant uterus by Listeria during gestation and the bacterium crossing the intestine after the animal ingesting contaminated soil, water or food.

In the fall of 2011 in multiple states including Colorado and New Mexico, a total of 146 persons were sickened, 30 people died, and one woman miscarried after eating cantaloupe contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes.(3) The sugar glider in this case was known to eat cantaloupe in its diet. Listeria monocytogenes has 11 different serotypes that can be distinguished from one another using molecular techniques. Using pulse field gel electrophoresis, the serotype of the L. monocytogenes isolated from the sugar glider was not the same as the serotype of the L. monocytogenes isolated from the cantaloupe associated with the listeriosis outbreak in people. Nevertheless, this case illustrates the One Health concept of the potential of infectious agents to infect veterinary species and humans that are sharing the same environment and ingesting the same food and water.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007: 405-408.

3. Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/listeria/outbreaks/cantaloupes-jensen-farms/120811/index.html. December 8, 2011 (Final Update). Accessed June 11, 2012.Â

4. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Rabbit. In: Percy DH, Barthold SW, eds. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell; 2007: 278-280.

5. Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Leonard FC, FitzPatrick ES, Fanning S, Hartigan PJ. Listeria species. In: Quinn PJ, Markey BK, Leonard FC, FitzPatrick ES, Fanning S, Hartigan PJ, eds. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011: 217-221.

6. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:492-493.

7. Walker RL. Listeria. In: Hirsh DC, MacLachlan NJ, Walker RL, eds. Veterinary Microbiology.2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell; 2004:185-189.

8. Warner SL, Boggs J, Lee JK, et al. Clinical, pathological, and genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes causing sepsis and necrotizing typhlocolitis and hepatitis in a foal. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012; 24(3):581-586.

9. Zachary JF. Nervous System. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012: 845-846.