Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

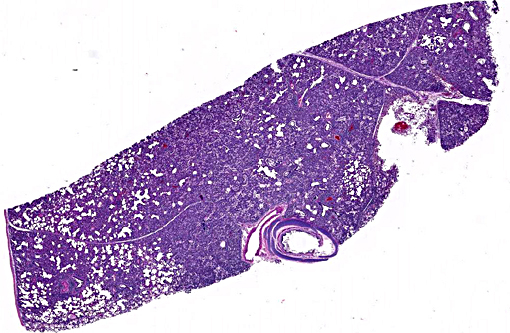

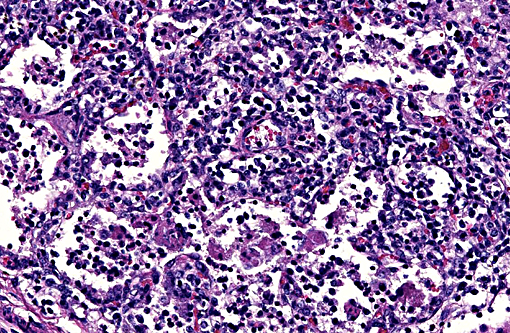

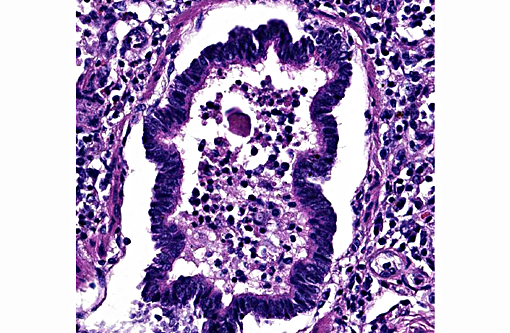

Lung: Diffusely, the interstitium is moderately to markedly expanded by predominantly macrophages, lesser lymphocytes and plasma cells, and few neutrophils. Alveolar lumina are markedly distended with fibrin and proteinaceous karyorrhectic cellular debris, numerous viable and degenerate neutrophils, macrophages, and lesser lymphocytes and plasma cells. Greater than 80% of alveolar walls are necrotic characterized by loss or replacement with fibrinoid necrosis. There is also scattered type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. In severely affected areas, bronchiolar lumina contain moderate amounts of fibrillar to homogenous eosinophilic material (fibrin and protein) with karyorrhectic necrotic cellular debris and neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells (Fig. 3). Occasional vessels contain fibrin thrombi. There is BALT hyperplasia and interstitial congestion in less inflamed areas.

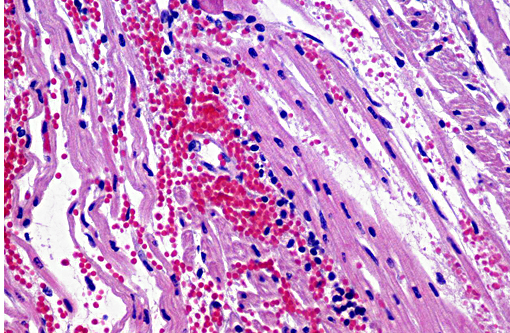

Heart: The subendocardium contains a locally extensive area of myocardial hemorrhage with a mild infiltrate of lymphocytes (Fig. 4). Within this area and the adjacent myocardium there is myofiber separation due to expansion of the interstitial space (edema). There is moderate perivascular edema around multiple epicardial vessels.

Haired skin: There is mild to moderate superficial perivascular edema and infiltrates of small number of lymphocytes and plasma cells. There is moderate to marked orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. The stratum corneum is lined by few small accumulations of ovoid 2x3 micrometer, pale basophilic yeasts (Candida sp.). There are few small accumulations of coccoid bacteria that are often in pairs or small clusters (Streptococcus and/or Staphylococcus sp.). These organisms are often associated with small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Severe diffuse lymphohistiocytic and necrotizing interstitial pneumonia, etiology PRRSV.

Lung: Mild to moderate multifocal suppurative bronchointerstitial pneumonia.

Heart: Mild focally extensive lymphocytic and hemorrhagic myocarditis.

Lymph node and Peyer's patches: Severe diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia.

Haired skin: Moderate to severe diffuse orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with intracorneal yeasts and bacteria and mild suppurative crusting.

Haired skin: Mild superficial perivascular lymphoplasmacytic dermatitis.

Lab Results:

Virology: Lung tissue was positive for PRSSV by PCR. Samples were negative for Swine influenza virus and pseudorabies virus.

Culture and Sensitivity: Streptococcus progenies was isolated from the lung. The isolate was susceptible to carbenicillin, and not susceptible to tobramycin, norfloxacin, vancomycin, gentamycin, sulfa/trimethoprim and erythromycin.Nutritional analysis for vitamin E levels in the liver were normal. Trace nutrient analysis of the liver revealed adequate levels of selenium, zinc and copper. Iron levels were slightly elevated at 674 micrograms/gram (normal reference interval is 300-600). Cobalt and molybdenum were also analyzed, but reference values for pigs were unavailable.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

There are 2 clinical manifestations of PRRS: A reproductive phase and a respiratory phase. The reproductive form of the disease typically lasts 1-4 months, and is characterized by increased numbers of stillborn and mummified fetuses, late term abortion, and weak-born piglets. Anorexia and agalactia are also often present further contributing to preweaning mortality. Suckling piglets characteristically develop a thumping respiratory pattern. The respiratory form of the disease is characterized by a chronic interstitial pneumonia clinically associated with dyspnea with no associated cough. Post-weaning pigs are primarily affected and have a significant reduction in daily weight gain and increased mortality up to 10-25%.1 Secondary bacterial infections are common. Histologically, the virus results in a severe necrotizing interstitial pneumonia with sparing of the bronchiolar epithelium. Alveolar septa are thickened by infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages, which also infiltrate the alveolar lumina, along with small numbers of neutrophils. Scattered alveoli will contain karyorrhectic cellular debris. There may be variable type II pneumocyte hyperplasia. Lymphoid hyperplasia is a characteristic feature of PRRSV infection, along with scattered apoptosis of follicular lymphocytes. Perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages may be present in several organs including the nasal mucosa, heart, kidney, and brain.

This virus is very contagious among pigs, and is transmitted via several routes of exposure including parenteral, intranasal, intramuscular, oral, vaginal and intrauterine. The virus replicates in monocyte-derived cells and is shed in blood, semen and oral fluids. Subclinical carriers are common, attributing to the endemic nature of the disease and difficulty in eradication once it has been introduced into a herd.(5)

In this case, the suppurative bronchointerstitial pneumonia is secondary to opportunistic bacterial invasion. Streptococcus progenies was isolated from the lung in this case. This is a human pathogen, warranting consideration of this being a potential zooanthroponosis or a possible contaminant. The lesions in the heart are likely a sequela to the PRRS virus. Another differential to rule out for this lesion is encephalomyocarditis virus. This animal had a rough hair coat and areas of alopecia, which were histologically associated with hyperkeratosis and intracorneal coccoid bacteria and yeasts, suggestive of Candida sp. Similar mycotic agents and numerous rod bacteria were also present in the lumen of the intestine. The overgrowth of yeasts and bacteria is likely due to an immunosuppressive state of the animal secondary to viral infection. Prolonged antibiotic use can also cause a similar overgrowth of yeast.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, necrotizing, subacute, diffuse, marked with type II pneumocyte hyperplasia.

2. Lung: Bronchopneumonia, neutrophilic, acute, multifocal, moderate.

Conference Comment:

The PRRS virus results in significant economic losses in the swine industry worldwide, with annual cost estimates around $600 million in the United States alone. It is a species specific virus that has a high mutation rate, which may result in outbreaks in previously vaccinated herds. As mentioned above, routes of transmission and shedding are diverse and duration of infection and shedding may vary depending on virus strain. Additionally, prolonged infection is a key feature of the virus, as with other arteriviruses.(3)

Clinically, PRRS disease typically occurs in clinical stages, the first beginning with viral infection and replication in alveolar macrophages followed by spread to alveolar pneumocytes, most likely via leukocyte trafficking. The virus appears to have a predilection for infection of macrophages. The presence of infected alveolar macrophages results in alveolar damage and acute interstitial pneumonia. Degeneration and necrosis of pneumocytes occur as a result of the acute inflammatory response. Being an enveloped virus, the agent is able to infect the cell without causing cell death. However, both infected and non-infected macrophages release proinflammatory cytokines, recruiting additional inflammatory cells, and causing significant tissue damage. Histologically, the results of the cytokine cascade are seen as alveoli filled with inflammatory cells and debris, as observed in this pig case. Infected macrophages drain to regional lymph nodes where they infect lymphocytes and other macrophages, resulting in clinically large, firm, grossly edematous nodes. In the second clinical stage of disease, the virus spreads to other organ systems and becomes a persistent infection. This typically results in more generalized infection of lymph nodes and the reproductive organs, among other tissues such as tonsil and spleen.

At the molecular level, the PRRS virus is able to prevent infected macrophages/monocytes from functioning properly during phagocytosis, antigen presentation and cytokine release, thus hampering the immune response.(4) Specifically, infection results in impaired expression of cytokines such as TNFα, IL-12 and IFNγ.(2) Additionally, the virus increases the release of IL-10 from infected cells, which is immunosuppressive, affecting both the innate and adaptive immune response.(4)

References:

1. Cahn CM, Line S. The Merck Veterinary Manual. 10th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc.; 2010:661-663.

2. Garcia-Nicolas O, Quereda JJ, Gomez-Laguna J et al. Cytokines transcript levels in lung and lymphoid organs during genotype 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014;160(1-2):26-40.

3. Perez AM, Davies PR, Goodell CK. Lessons learned and knowledge gaps about the epidemiology and control of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in North America. JAVMA. 2015;246(12):1304-1317.

4. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of Microbial infection. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:214-215.

5. Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, et al. Diseases of Swine. 10th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2012: 461-480.