Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 13

January 3rd, 2018

CASE II: K13-8163-B (JPC 4070254).

Signalment: 8 year-old castrated male Saint Bernard, Canis familiaris, canine.

History: Firm, non-pruritic, non-seasonal, longer than a year infiltrative disease within the eye; discrete symmetrical, 1-5 cm (an enucleated globe was received for histopathologic evaluation).

Gross Pathology: None.

Laboratory results:

None provided.

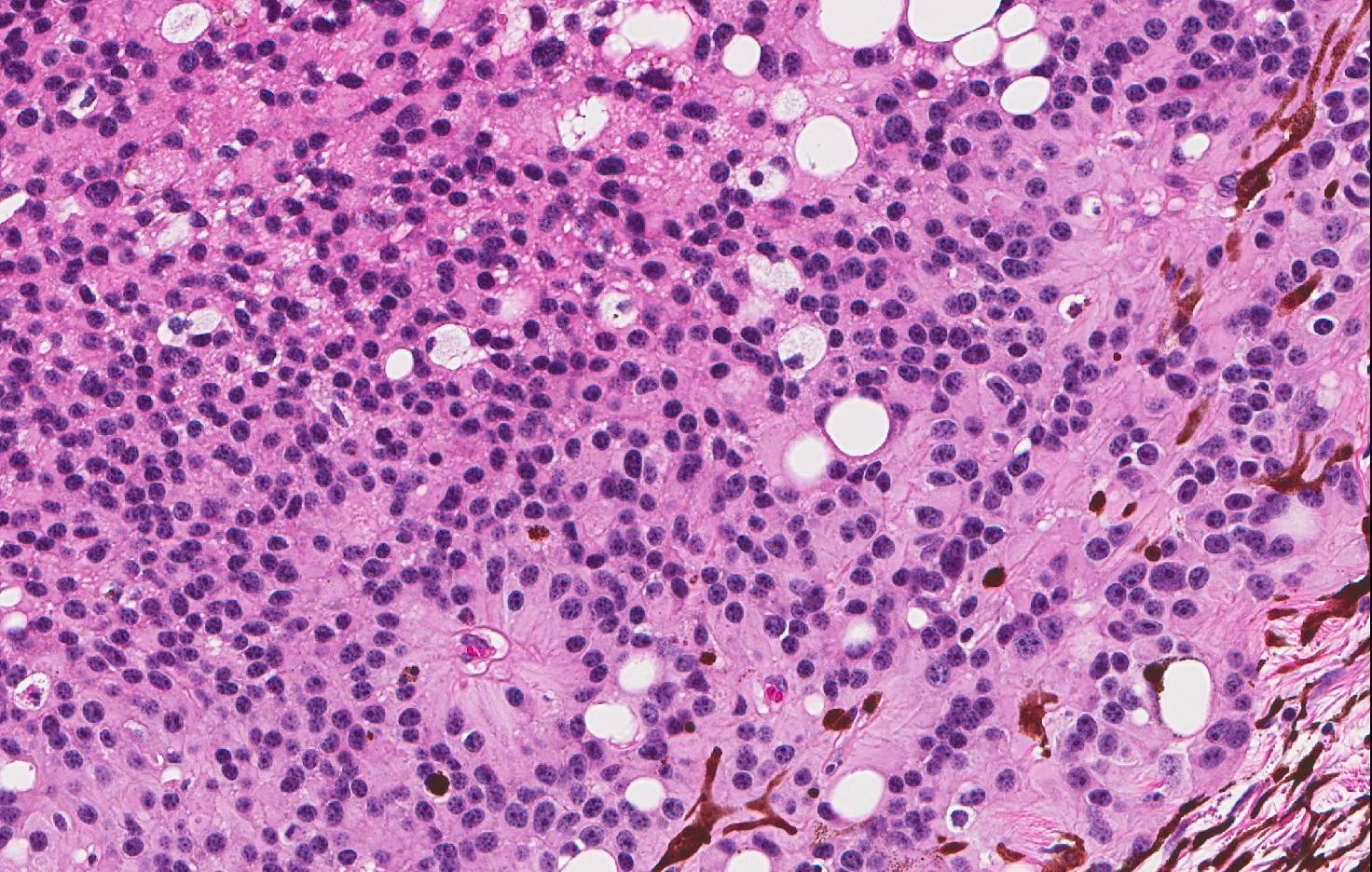

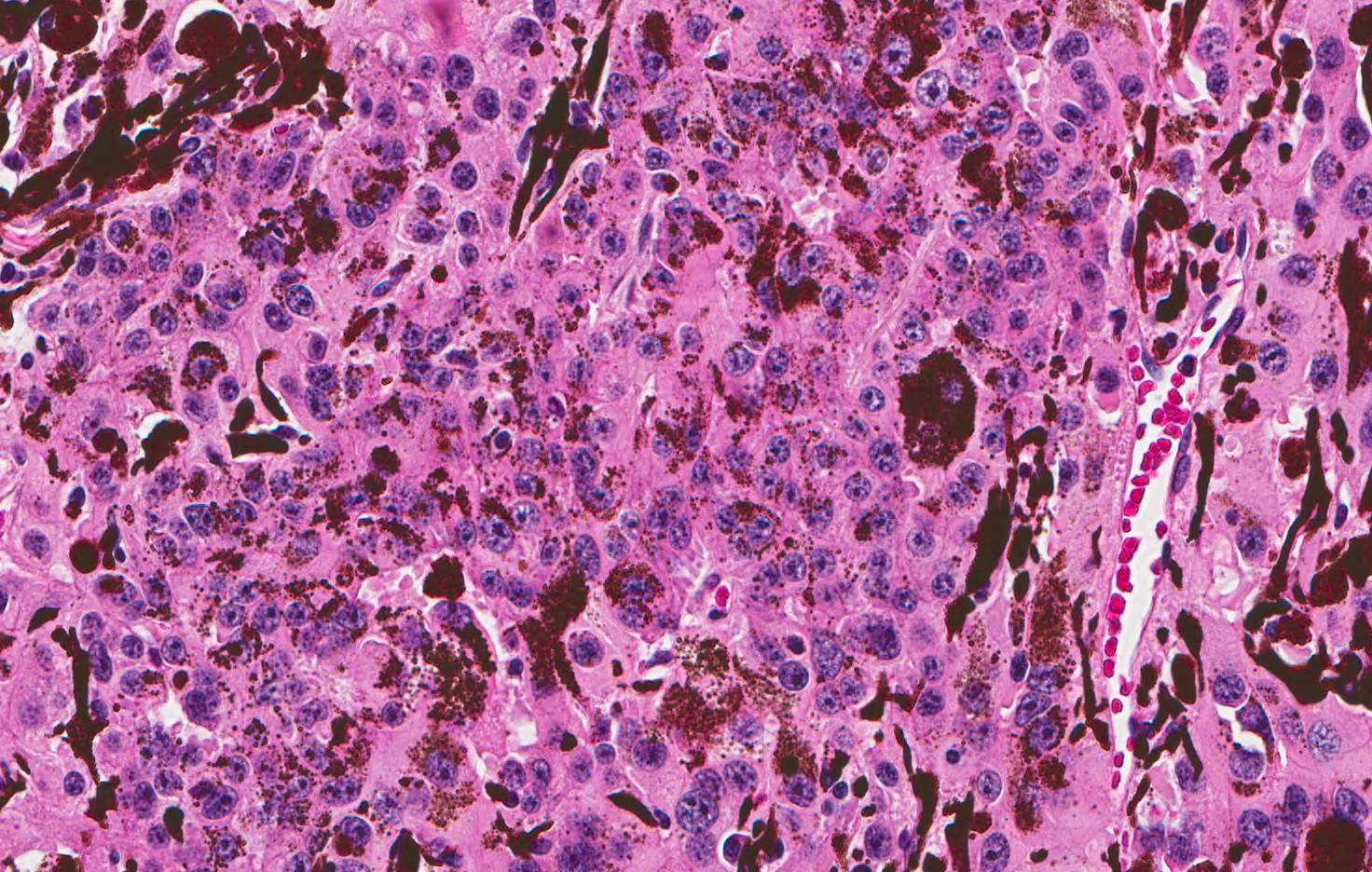

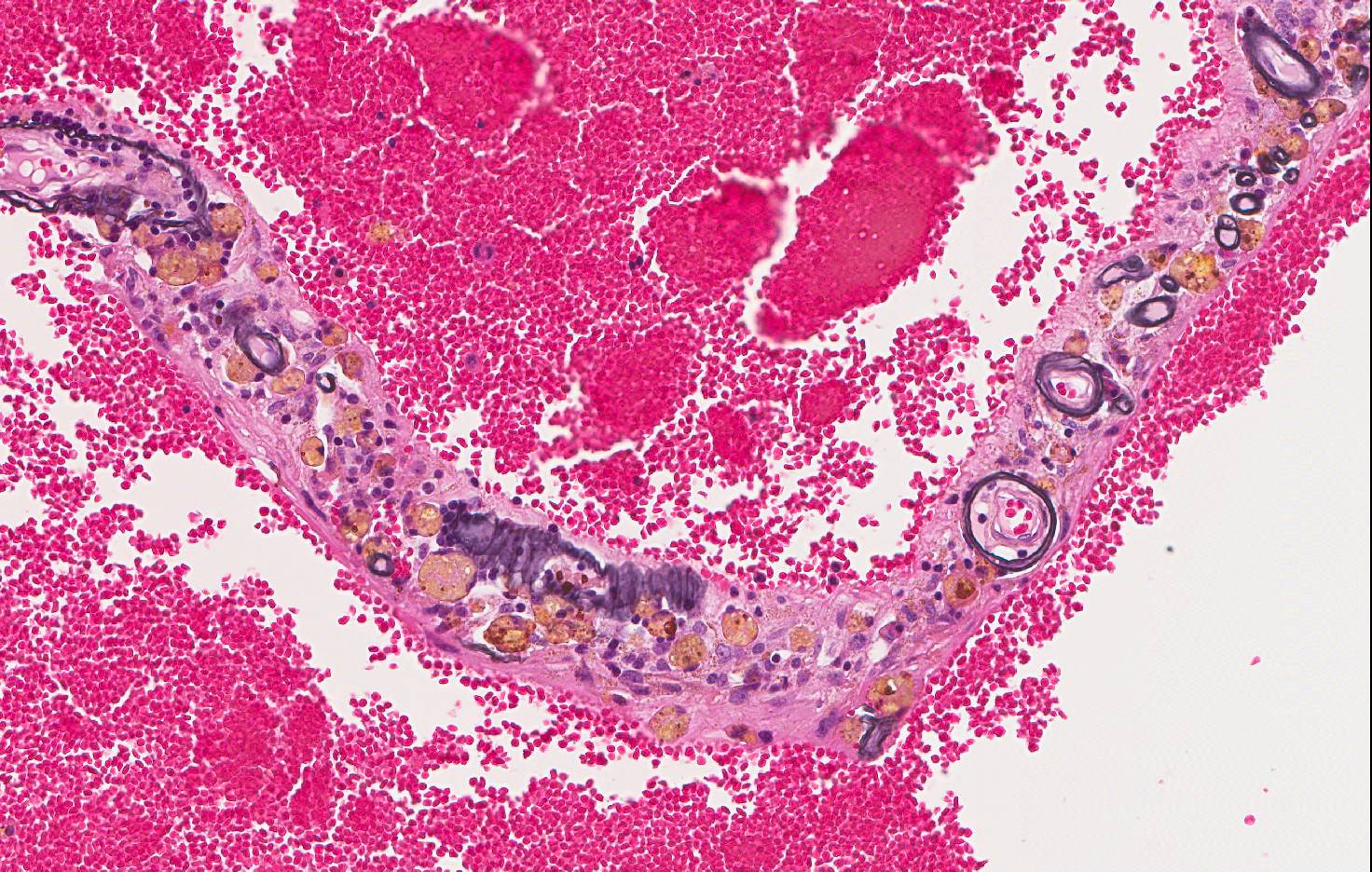

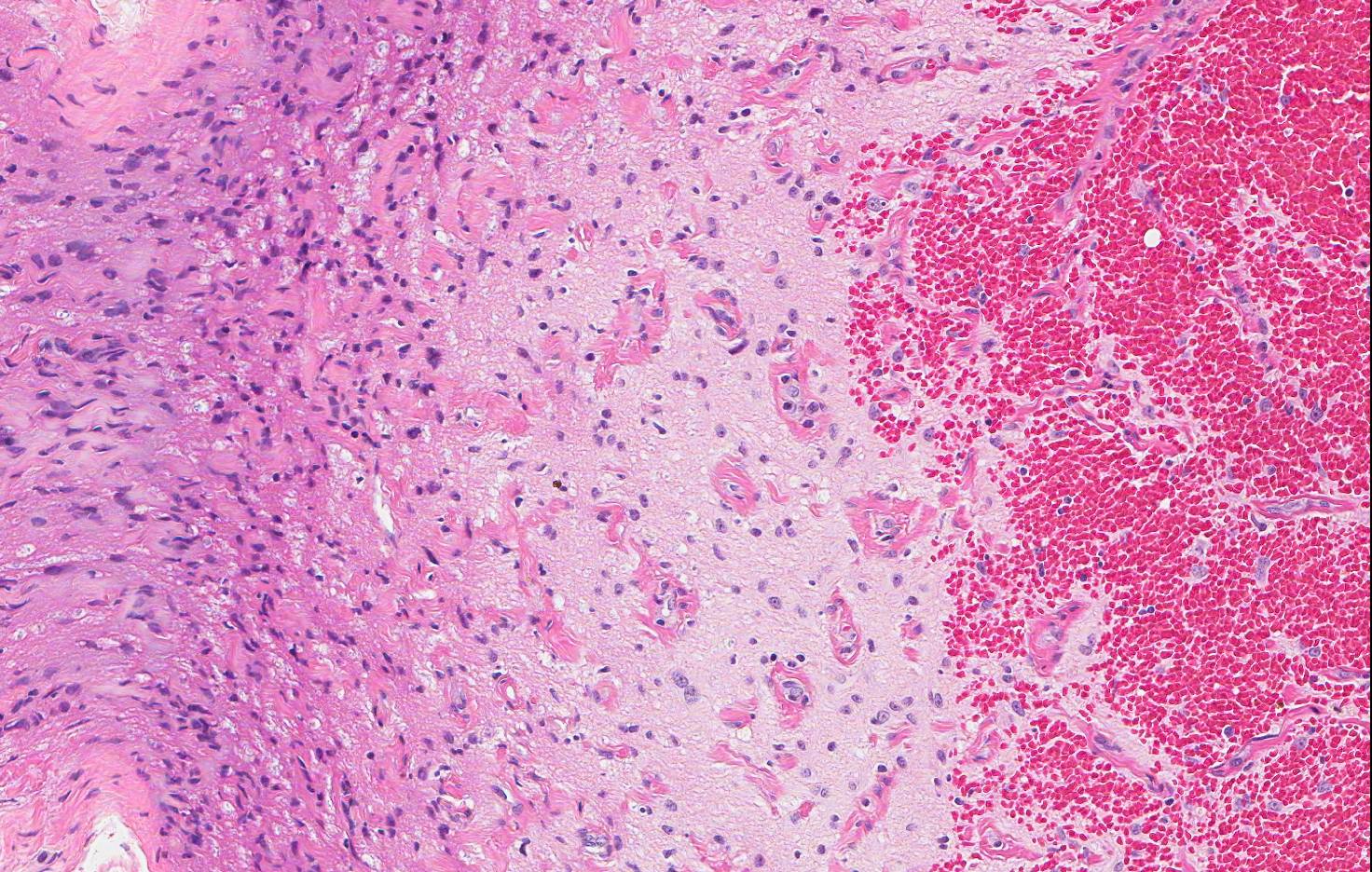

Microscopic Description: The slide contains a partial cross section of a canine globe. The globe has an unencapsulated mass arising from the ciliary body within the anterior uveal tract between the iris and lens. The mass is composed of tightly packed sheets and cords of polygonal cells and supported by a very fine vascular stroma. Neoplastic cells have indistinct cell borders, moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval nuclei with finely stippled chromatin. Pseudorosettes and occasional large bone formation are present. There is moderate anisokaryosis and anisocytosis. Mitotic figures are 7 in 5 HPF. There are variably-sized cavitated spaces containing blood or eosinophilic material and melanophages throughout the mass. The mass is not invading the sclera but is filling the iridocorneal angle and displacing the lens posteriorly. There is abundant hemorrhage filling the posterior and anterior chamber occasional associated to hematin-laden macrophages and fibrosis. The retina exhibits atrophy of the nerve fiber and ganglion cell layers. The lens has few eosinophilic spherical globules (Morgagnian globules) and bladder cells within subcortical areas. The special stain PAS reveals a complex network of delicate PAS positive basement membranes surrounding groups of neoplastic cells.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

- Eye: Pigmented iridociliary adenoma.

- Eye: Secondary glaucoma and retinal atrophy with cataractous change.

Contributor’s Comment: Histopathological features are most consistent with a benign iridociliary adenoma in this case. The tumor is considered benign because is not invading the sclera or choroid, and lacks cellular pleomorphism. Iridociliary adenomas and adenocarcinomas arise from the pigmented or non-pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body and iris, which are of neuroectoderm origin.2,7 They are the second most common primary intraocular tumor of dogs, occasionally seen in cats and infrequently seen in other species.2,5 In general, morphologic patterns for iridociliary epithelial tumors include papillary, solid, palisading ribbons or ribbon-cord, tubular, cystic and anaplastic. The most common secondary abnormality detected with these tumors is glaucoma.5 However; other complications include uveitis, cataract, loss of vision and, less frequently, retinal detachment, lens luxation and corneal decompensation.1 Although, iridociliary adenocarcinomas are extremely rare and usually do not metastasize, metastasis is a late stage phenomenon and unlikely in the absent of extensive scleral invasion.8 Iridociliary epithelial tumors, benign and malignant, can be diagnosed based on histopathological features; however, adenomas were indistinguishable from adenocarcinomas by biopsy in one study.1 Additionally, these tumors almost always retain abundant basement membrane production that can be accentuated with PAS staining.3 An unique characteristic is the positive staining for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin in adenomas.6 The cells also stain for S-100 and neuron-specific enolase.6 On the other hand, the malignant version is vimentin and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 positive.8

JPC Diagnosis:

- Globe: Pigmented iridociliary adenoma with drainage angle occlusion, hyphema and subretinal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment and atrophy, Saint Bernard, canine.

- Retina, vessels: Ferrugination, multifocal, severe.

Conference Comment: Iridociliary epithelial tumors are of neuroectodermal origin and arise from the epithelial cells of either the iris or ciliary body. Primary iridociliary epithelial tumors generally exhibit one of the following criteria: noninvasive growth of epithelial cells that extends into the aqueous adjacent to the iris or ciliary body, pigmented epithelial cells, or thick basement membrane structures on the cell surface.

The incidence of benign (adenoma) and malignant (adenocarcinoma) iridociliary epithelial tumors are about equal; however, ocular melanomas are about twice as common as iridociliary tumors and are the most frequent primary intraocular tumor in the dog. Adenomas are easier to distinguish from melanomas because they are often limited to the ciliary body, whereas, adenocarcinomas, like melanomas, are characterized by a more invasive growth pattern, may extend through the iris base or pupil and are potentially metastatic. The typical microscopic growth patterns of iridociliary adenoma and adenocarcinoma are described by the contributor above. The key microscopic difference between the two depends on extension into the sclera and the presence of anaplasia. If present, these features support a diagnosis of iridociliary adenocarcinoma.

Interestingly, these tumors often appear non-pigmented grossly, regardless of the extent of microscopic pigmentation. In addition to the immunohistochemical characteristics noted above, Alcian blue can often be used to identify hyaluronic acid secretions, which are commonly associated with cells of iridociliary epithelial origin.4 Historically, tumors of the ciliary body have been induced in laboratory beagles via intravenous injection of 226Ra and 228Ra. These tumors were not identified as of neural crest origin, ruling out melanoma, and were assumed to represent unique radium-induced neoplasms arising from the pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body.4

The conference moderator also discussed the significance of the location of new vessels within the corneal stroma. Vascularization of the deep corneal stroma (as seen in this case) tends to be associated with intraocular disease, while more external vessel formation is typically due to corneal trauma. Additionally, a prominent cyclitic membrane was noted by conference participants, arising from the ciliary body and extending to the posterior aspect of the lens. Finally, conference participants discussed the extensive hemorrhage within the posterior segment of the eye. Although the reason for this is unclear, some participants postulated that the patient was hypertensive, while others suggested the possibility of trauma to a non-sighted eye. Of note, within the retinal remnant vessel walls often appear deeply basophilic and are highlighted with Prussian-blue stain, which suggests accumulation of iron-containing material, a process known as “ferrugination”. This could be associated with the chronic hemorrhage noted above.

Contributing Institution:

State of Tennessee

Department of Agriculture

Consumer and Industry Services

Kord Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory

References:

- Beckwith-Cohen B, Bentley E, Dubielzig RR. Outcome of iridociliary epithelial tumour biopsies in dogs: a retrospective study. Vet Record. 2015;176(6):147. doi:10.1136/vr.102638

- Dubielzig RR. Tumors of the eye. In: Meuten DJ, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. Ames, IA: Iowa State Press; 2002:749-750.

- Dubielzig RR, Steinberg H, Gavin H, Deehr A. J, Fisher B. Iridociliary epithelial tumors in 100 dogs and 17 cats: a morphological study. Ophthal. 1998;1:223-231.

- Hendrix D. Diseases and surgery of the canine anterior uvea. In: Gelatt KN, Gilger BC, Kern TJ, eds. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 5th Vol. 2. Ames, IA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013:1181-1182.

- Njaa B, Wilcock B. The ear and eye. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1229-1230.

- Wilcock B. Eye and ear In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007:542.

- Wilcock B, Dubielzig RR, Render JA. Histological Classification of Ocular and Otic Tumors of Domestic Animals. Second series. Vol IX. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/ American Registry of Pathology; 2002:25.

- Zarfoss MK. and Dubielzig RR. Metastatic iridociliary adenocarcinoma in a Labrador retriever. Vet Path. 2007;44:672-676.