Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 22

15 April, 2020

CASE III: 61726-1 (DVD) (JPC 4117676).

Signalment: 2-year-old, female Angolan Colobus monkey (Colobus angolensis palliatus)

History: This monkey was found down and unresponsive at morning check and transported to the hospital immediately. She had no significant history prior to this event, and keepers reported no recent cause for concern. On physical examination she was obtunded and ataxic, with decreased lung sounds on the left and mild crackles on the right. A small abrasion was present on the left ischial pad. On a CT scan, there was a severe, diffuse, nodular/bronchiolar pattern throughout the lungs with a left-sided alveolar pattern. No apparent soft tissue asymmetry was noted. The animal failed to respond to supportive care and was humanely euthanized later the same day due to poor prognosis.

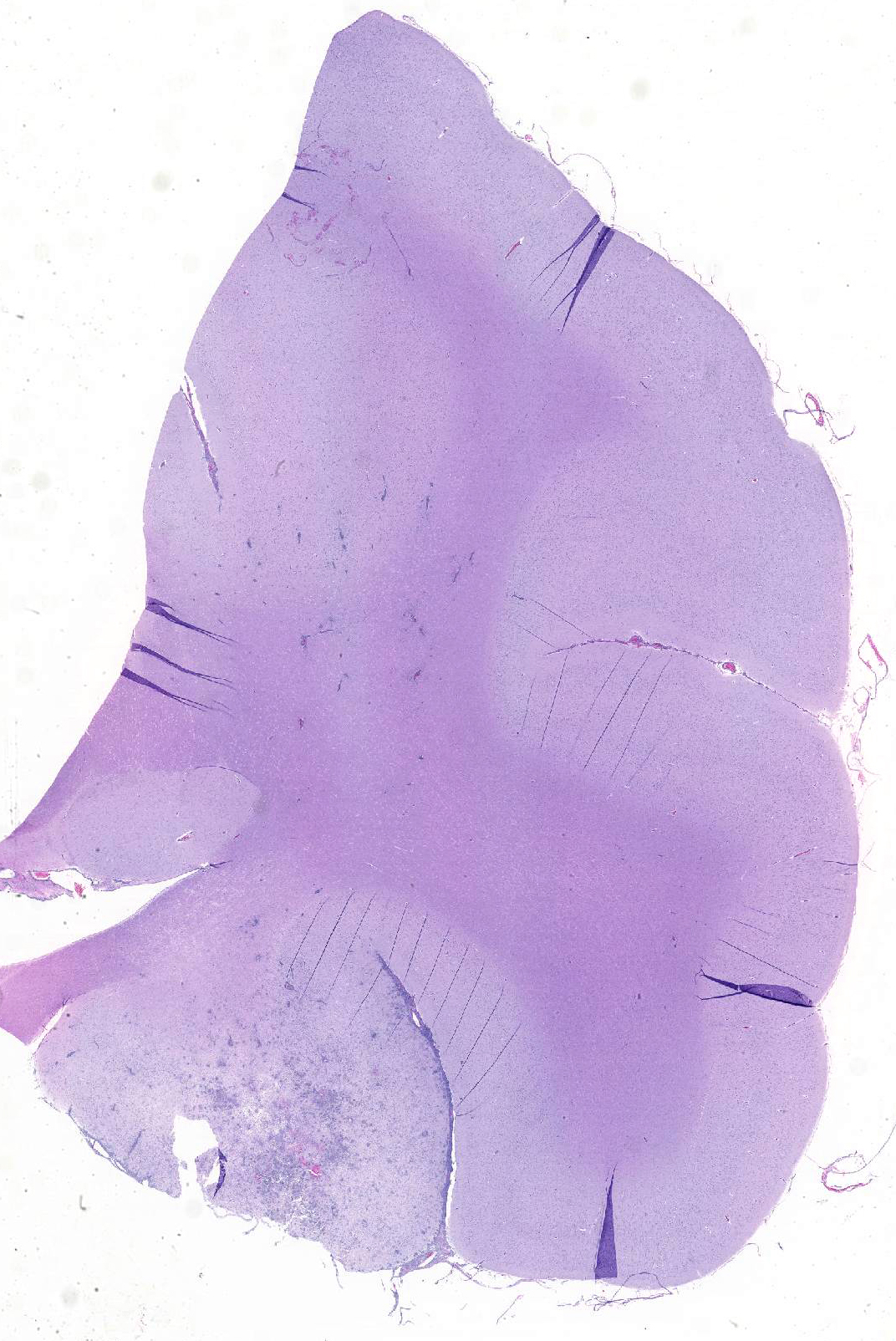

Gross Pathology: Postmortem examination revealed evidence of interstitial pneumonia, nephritis characterized by coalescing tan, red-rimmed nodules, and a prominent focus of hemorrhage in the rostral left cerebrum.

Laboratory results:

Clinical pathology:

- A CBC showed a mild non-regenerative anemia (HCT 30), thrombocytopenia (158,000/ul), and increased fibrinogen (400 mg/dl). A serum chemistry was unremarkable.

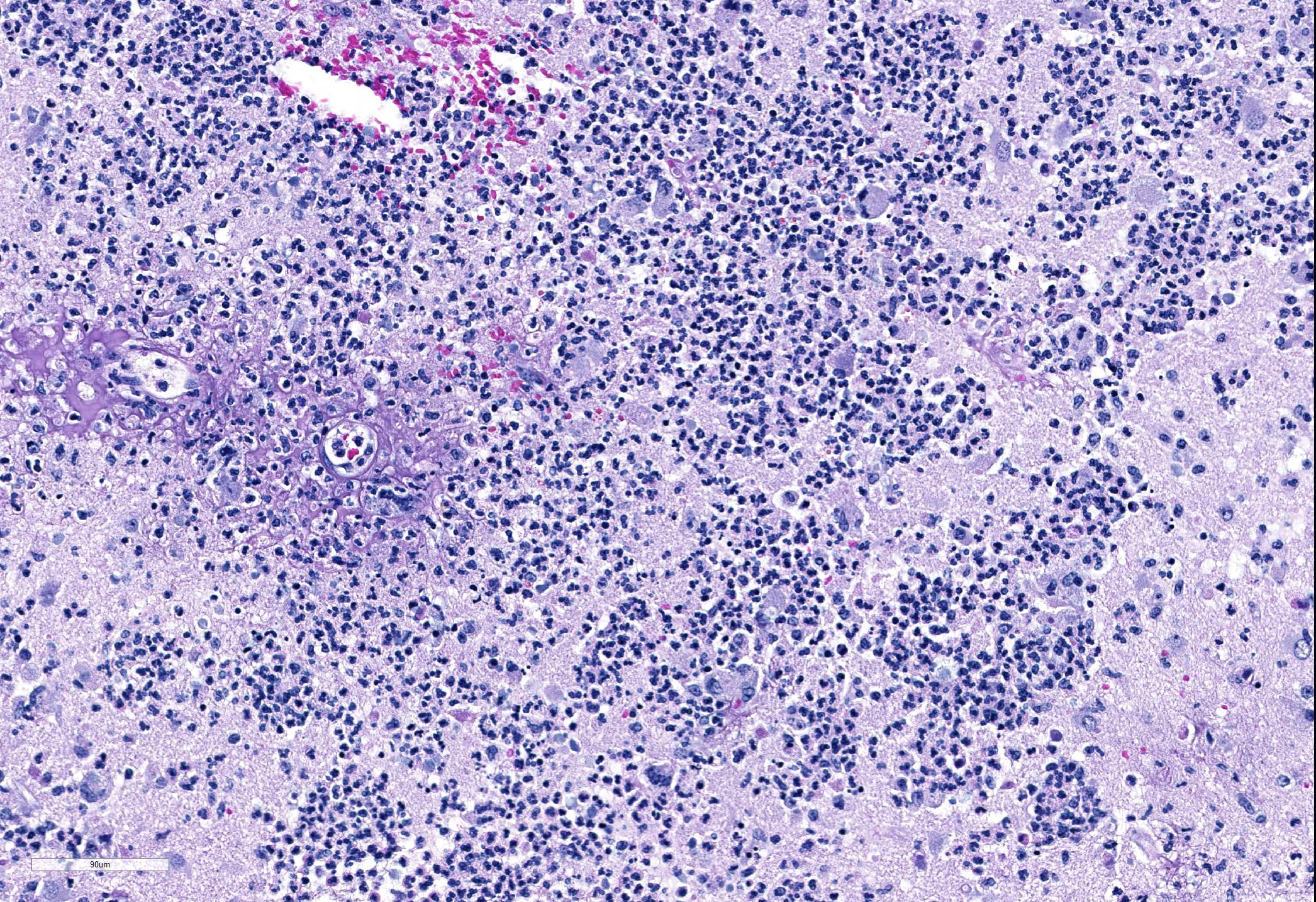

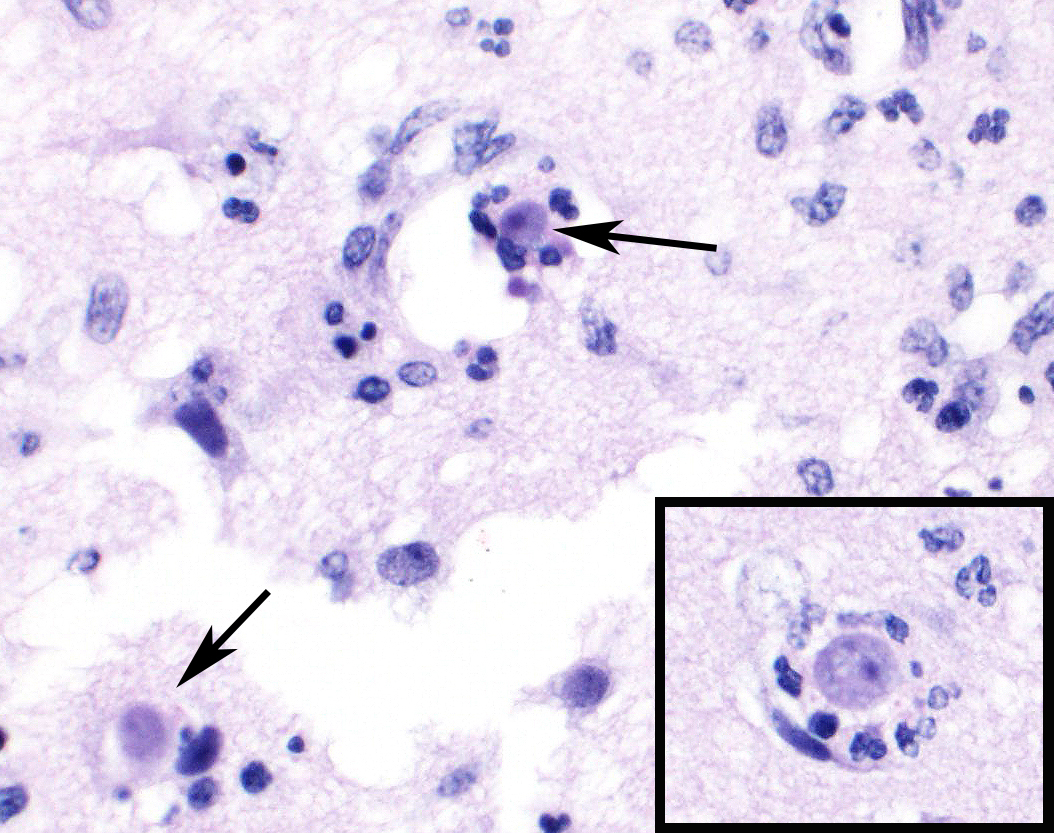

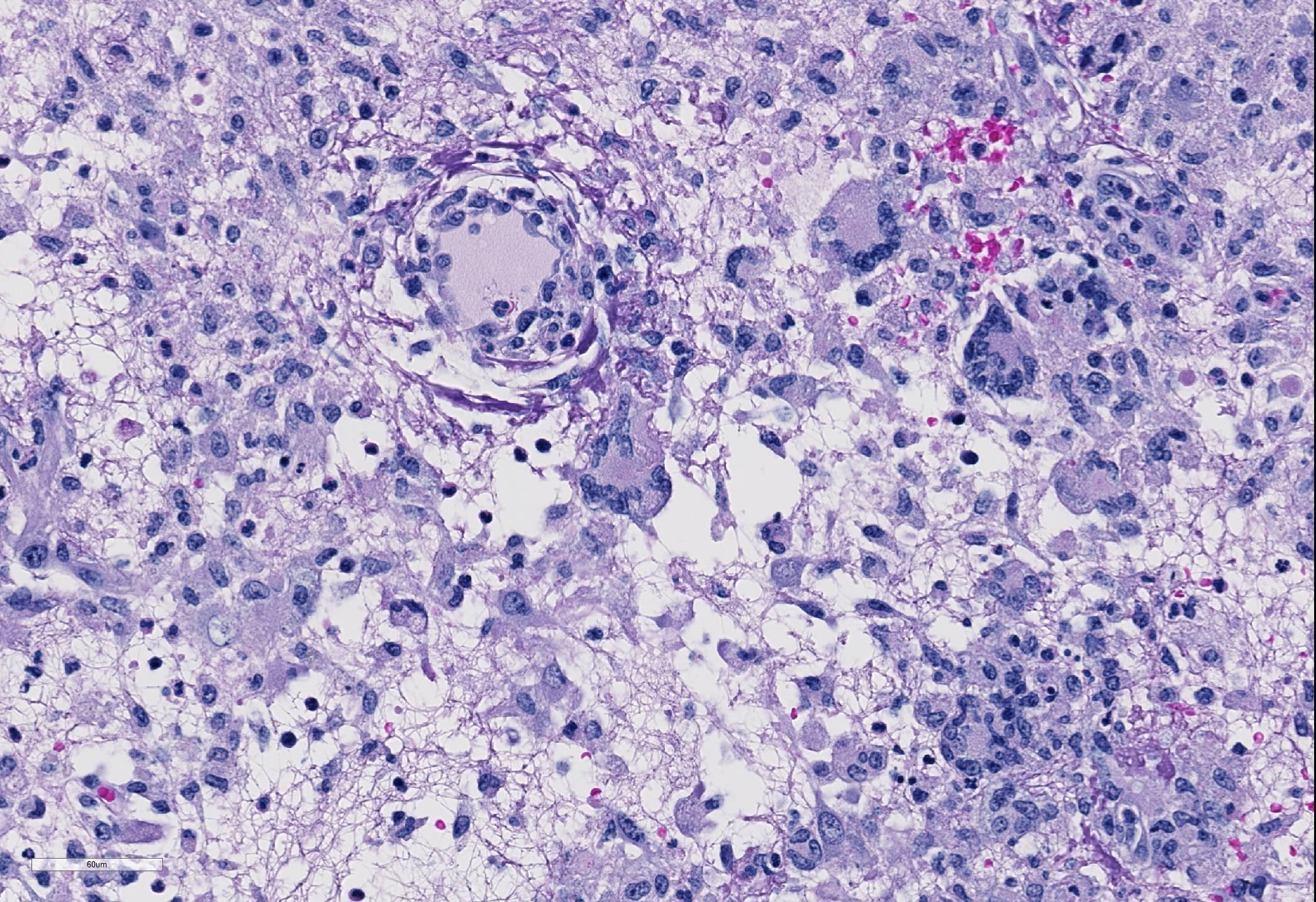

Microscopic Description: Cerebrum: Approximately 15-20% of the parenchyma, of which the majority is gray matter, is affected by multifocal to coalescing rarefaction, necrosis, and hemorrhage, and is infiltrated by large numbers of neutrophils with fewer histocytes and lymphocytes. Vessel walls in this region are frequently diffusely hyalinized, disrupted and expanded by eosinophilic fibrillar material and karyorrhectic debris (fibrinoid necrosis), and infiltrated by neutrophils (vasculitis). Moderate numbers of amoebic trophozoites measuring from 15-30 micrometers in diameter with a 4-6 micrometer karyosome (nucleus), up to three endosomes (nucleoli), and amphophilic, lacy to vacuolated cytoplasm are scattered throughout the inflamed region. There are increased numbers of glial cells (gliosis), and astrocytes have large nuclei with open chromatin (reactive astrocytosis). The meninges are expanded by large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes with fewer neutrophils. Vessels in surrounding parenchyma are surrounded by large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, which multifocally infiltrate vessel walls.

lmmunohistochemistry:

Balamuthia immunohistochemistry: positive

Acanthamoeba immunohistochemistry: negative

Naegleria immunohistochemistry: negative

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Brain, cerebrum: Severe, marked, regionally extensive, necrotizing, pyogranulomatous, meningoencephalitis with cavitation, fibrinoid vascular necrosis, vasculitis, and amoebae.

Contributor?s Comment: Infections with free-living amoeba are an emerging disease in both human and animal populations. The major differentials for free-living amoeba infecting animal and human tissues include Balamuthia sp, Acanthamoeba sp, and Naegleria fowleri. These three organisms can be difficult to distinguish from each other based on light microscopy alone except for a few distinguishing features. The distinguishing feature of Naegleria fowleri, is that it does not form cysts in the brain, whereas Balamuthia sp. and Acanthamoeba sp. do.8

Acanthamoeba and Balamuthia are very similar morphologically and can be difficult to diagnose without additional diagnostics such as immunohistochemistry or PCR. One feature that may assist in distinguishing between the two is that Balamuthia can have multiple nucleoli within its trophozoite stage, whereas Acanthamoeba only has one nucleolus. Also, Balamuthia trophozoites are slightly larger and tend to be more pleomorphic than Acanthamoeba trophozoites.5 The size of the amoeba (trophozoites 15-30 micrometers in greatest dimension) along with the occasional presence of multiple endosomes or nucleoli in this case is consistent with Balamuthia mandrillaris, which was subsequently confirmed by immunohistochemistry.

Balamuthia mandrillaris was first discovered in a 3-year old female mandrill baboon

(Mandrillus sphinx) from the San Diego Zoo Safari Park that died of amoebic encephalitis in 1986. The species name mandrillaris comes from this index case.7 Since the first case, additional sporadic cases have been identified at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park over the years.5 In addition, the agent was subsequently found to be an important human pathogen, explaining a number of historical human cases of amoebic encephalitis that failed to stain with antibodies against Acanthamoeba and Naegleria..1

Balamuthia mandrillaris is a soil-dwelling organism. The pathogenesis of the infection remains uncertain, but open skin lesions are thought to be a risk factor in human cases.6 The animal in this case did have an abrasion on an ischial pad, which could have been a portal of entry. Exposure to blowing dust, mud puddles, or other soilcontaminated water are thought to be additional potential risk factors.4 These infections are not transmissible and are not zoonotic. Individuals infected with free-living amoeba tend to be immunocompromised in some way, with a number of human patients being infected with AIDS6; however, immunocompromise is not required for infection. Morbidity is overall low, but mortality is relatively high with human and animal infections.4

Common organ systems infected in humans include skin and the central nervous system. Lesions are typically granulomatous and necrotizing. Unlike other free-living amoeba, Balamuthia mandrillaris can cause disseminated chronic infections that are indistinguishable from metastatic neoplasia.1 Overall, free-living amoeba infections are important to have as a differential for various presentations in both animal and human patients.

Contributing Institution:

San Diego Zoo Global

Disease Investigations

P.O. Box 120551

San Diego, CA 92112-0551

https://institute.sandiegozoo.org/disease-investigations

JPC Diagnosis: Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing and pyogranulomatous, focally extensive, severe with vasculitis, thrombosis, gliosis, and numerous amebae

JPC Comment: Free-living amebae are ubiquitous

protozoans in the environment, of which four generally are considered

pathogenic for humans and animals: Acanthamoeba, Balamuthia mandrillaris,

Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia pedata.1,3 As a

group, they may act as vectors for a wide range of pathogenic bacilli, as well

as hosts for a range of viruses, including coxsackieviruses and adenoviridae

pathogenic for humans. Other viruses, the so-called giant viruses, may act as

endocytobionts, including representatives of the Mimi-, Moumo-

and Megaviridae, as well as Pandoviridae. Human infections

with free-living amebae, while uncommon, are especially problematic due to

their high mortality, non-specific symptoms, and lack of effective treatment.

Balamuthia mandrillaris is also a cause of granulomatous amebic

encephalitis which usually results from hematogenous spread from soil-contaminated

wounds and which ranges in duration between Acanthamoeba and Naegleria

(discussed below). A recent review of human cases from the CDC?s free-living

ameba registry identified 109 cases in the US within the last forty years3

with 99% resulting in encephalitis; 6% had skin lesions as well. 68% of cases

were male, with people of Hispanic ethnicity most frequently affected, and

California, Texas, and Arizona had the most cases. Immunosuppressed patients

accounted for less than 40% of this study. Due to the non-specific clinical

signs and laboratory diagnostics, only 25% of patients received an antemortem

diagnosis of Balamuthia infection.3

In humans, Balamuthia is thought to enter by inhalation or cutaneous

wounds; hematogenous spread is supported by the tendency for trophozoites to

cluster around vessels, as well as its propensity to infect multiple organs.

In 2009, organ transplantation was identified as another method of transmission

with kidney recipients of a donor that died of Balamuthia encephalitis.3

Acanthamoeba appear to be most often associated with

disease in humans and animals, with 18 distinct genotypes based on nuclear

small-subunit ribosomal DNA rather than morphology. The most common condition

associated with infection in humans is a chronic keratitis, seen in

immunocompetent patients associated with improper handling of contact lenses,

exposure to contaminated water, or trauma. Risk factors of contact lens users

include the use of all-in-one solutions, showering while wearing contact

lenses, and poor contact lens hygiene.4 Other species of free-living

amoeba which may have been identified in cases of keratitis include Hartmanella,

Vahlkamphiae, and Allovahlkampfiae spelae.4

Granulomatous amebic encephalitis is a well-documented syndrome in humans

resulting from hematogenous spread, often from the lower respiratory tract or

skin lesions. It shows a chronic fatal progression with luckily only 150

documented cases worldwide.4 Due to its hematogenous origins,

areas of granulomatous inflammation are seen throughout all parts of the

brain. Cutaneous acanthamoebiasis is also an uncommon opportunistic condition

primarily seen in immunosuppressed patients, resulting in erythematous sores

and skin ulcers.4

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is another rare

fatal disease in humans caused by Naegleria fowleri. This condition

generally occurs in healthy children and adults swimming or bathing in in warm

freshwater ponds. Infective amebae migrate along olfactory nerves from the

nose to the brain; fatal infection proceeds rapidly and is almost always fatal.

Due to this unique entry portal, areas of lytic necrosis are clustered at the

base of the brain, hypothalamus, pons, and occasionally seen in posterior areas

such as the medulla oblongata.4

References:

1.Balczun C, Scheid PL. Free-living amoebae as hosts for and vectors of intracellular microorganisms with public health significance. Viruses 2017; 9:^%, doi 10-3390/v9040065.

2. Bravo FG, Alvarez PJ, Gotuzzo E. Balamuthia mandrillaris infection of the

skin and central nervous system: an emerging disease of concern to many specialties in medicine. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011 Apr;24(2):112-7.

3. Cope JR, Landa J, Nether cut H, Collier SA, Glaser C, Moser M, Puttagunta R, Yoder JS, Ali IK, Roy S. Th epidemiology and clinical features of Balamuthia mandrillaris disease in the United States, 1974-2016. Clin Inf Dis 2019, 68(11):1815-1822.

4. Krol-Turminska K, Olender A. Human infections caused by free-living

amoebae. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017 May 11 ;24(2):254-260.

5. Rideout BA, Gardiner CH, Stalis IH, et al. Fatal infections with Balamuthia mandril/aris (a free-living amoeba) in gorillas and other Old World primates. Vet Pa tho I. 1997 Jan;34( 1 ): 15-22.

6. Trabelsi H, Dendana F, Sellami A, et al. Pathogenic free-living amoebae: epidemiology and clinical review. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2012 Dec;60(6):399-405.

7. Visvesvara GS, Martinez AJ, Schuster FL, et al. Leptomyxid ameba, a new agent of amebic meningoencephalitis in humans and animals. J Clin Microbial. 1990 Dec;28(12):2750-6.

8. Visvesvara GS, Moura H, Schuster FL. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoeba: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS lmmunol Med Microbial 2007; 50:1-26.