CASE 2: VP18063 (4134595-00)

Signalment:

Two-year-old, male, four-toed hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris)

History:

He had 10-day history of lethargy and anorexia. Abdominal ultrasonography showed splenomegaly, and chest X-ray imaging revealed decreased permeability in the lung fields. Corticosteroid and antibiotic therapies were continued for 4 days, but he died eight days later.

Gross Pathology:

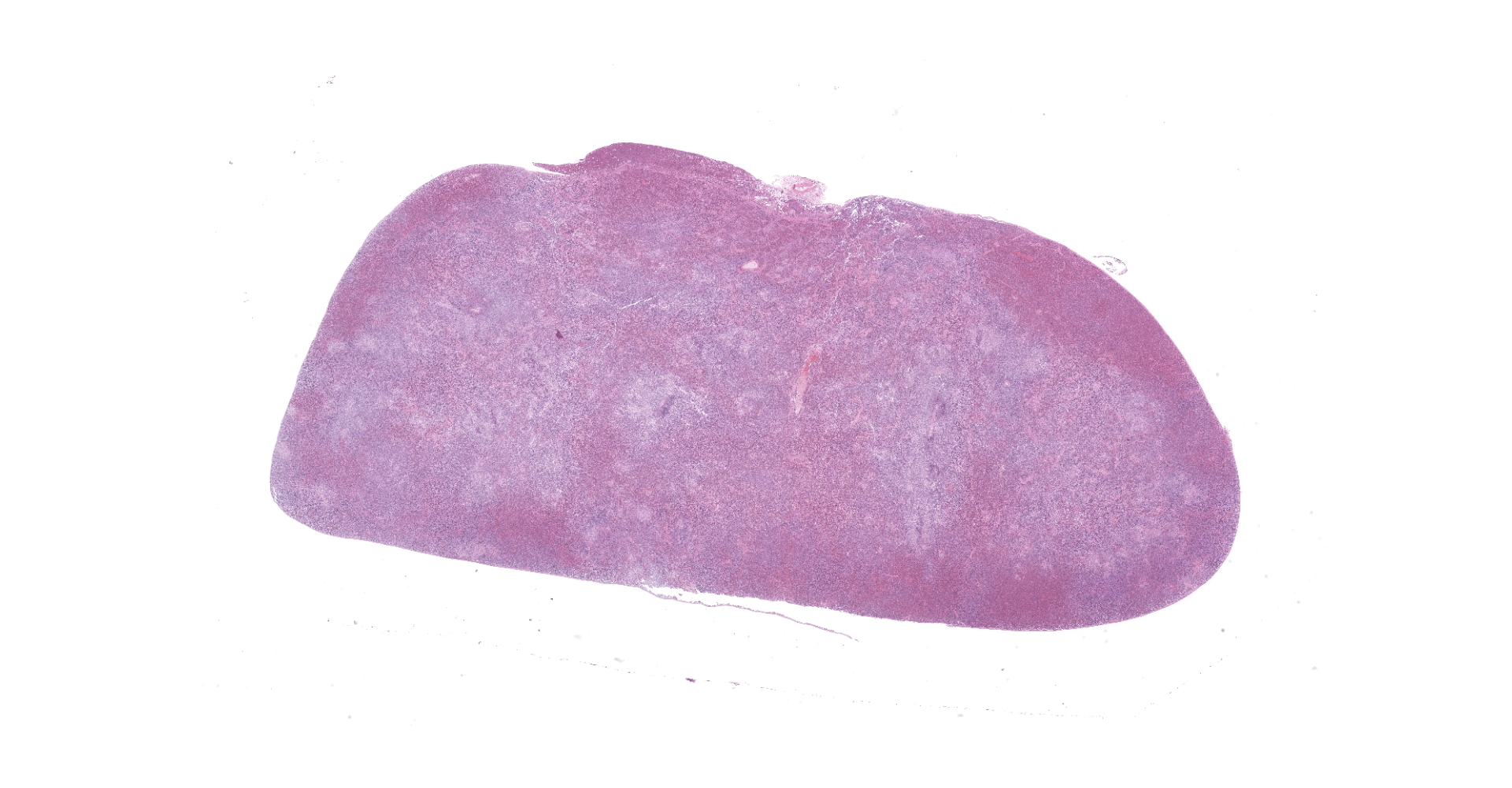

At necropsy, the hedgehog was thin and weighed 288 g (normal body weight is approximately 400 g). The left hindlimb was markedly swollen and on its distal end was a black scab. The spleen was discolored and markedly enlarged. The spleen, liver, and lung had multifocal, white foci of varying sizes (1 mm-4 mm). The left inguinal lymph node was moderately enlarged.

Laboratory results:

Peripheral blood smear: Peripheral blood smear showed prominent leukocytosis with a ratio of 11% stab cells (bands), 16% segmented neutrophils, 2% lymphocytes, 4% monocytes, and 67% eosinophils. Eosinophils were large (14?18 µm diameter) and round with abundant small, round, eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules. The nuclei were round to reniform and had coarse and aggregated chromatin pattern. Mature segmented eosinophils were sometimes observed.

PCR: Mycobacterium marinum was confirmed by broad-range PCR amplification of bacterial 16S rDNA and sequencing of paraffin tissues from the lung.

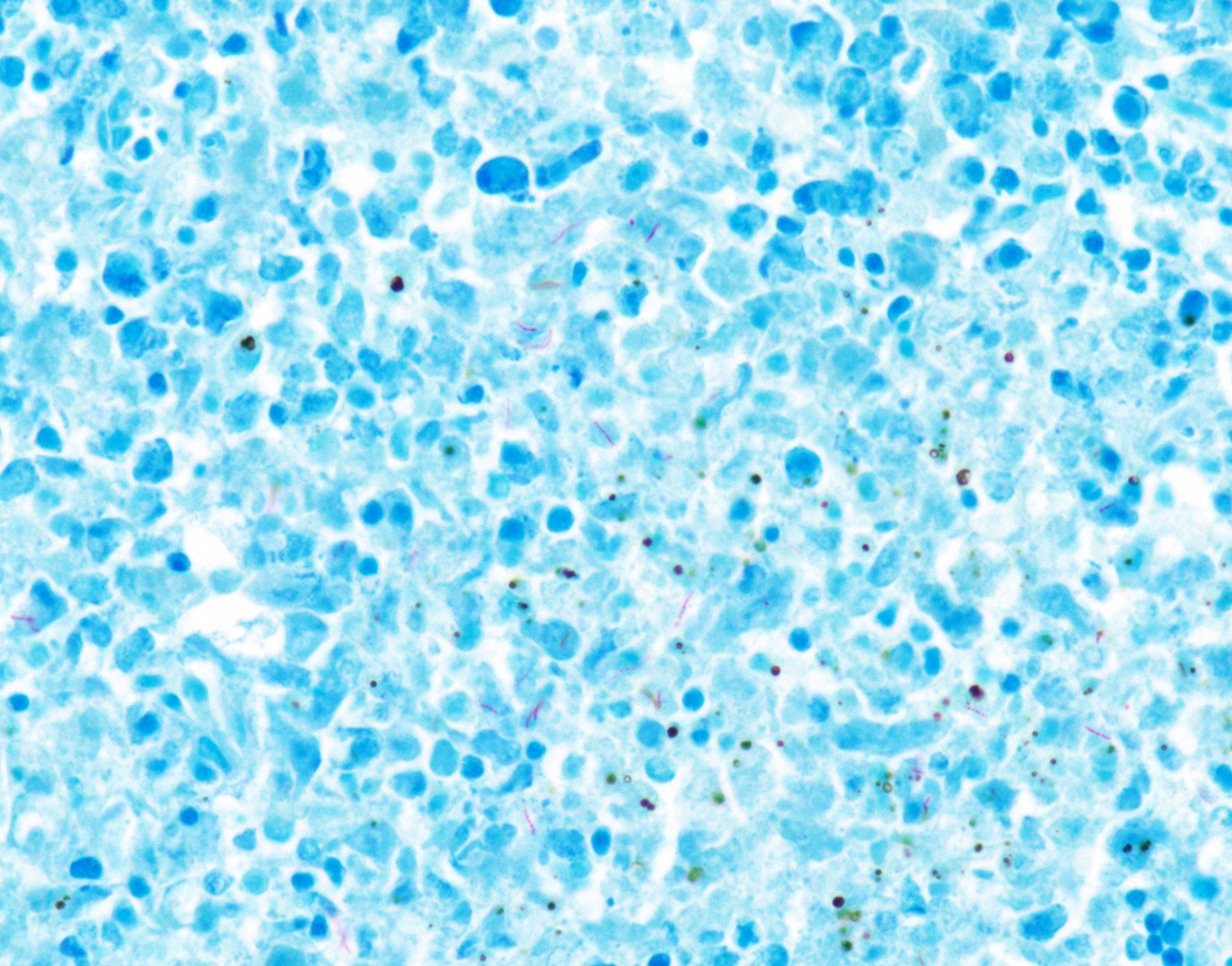

Special stain (Ziehl-Neelsen stain): Spleen, lung, liver, left inguinal lymph node, and distal end of left hindlimb: Moderate to large number of acid-fast bacilli were within the granulomatous lesion.

Immunohistochemistry: Spleen, lung, liver, left inguinal lymph node, and distal end of left hindlimb: Immunohistochemistry using rabbit polyclonal Mycobacterium bovis antibody confirmed the presence of intracellular and extracellular bacilli.

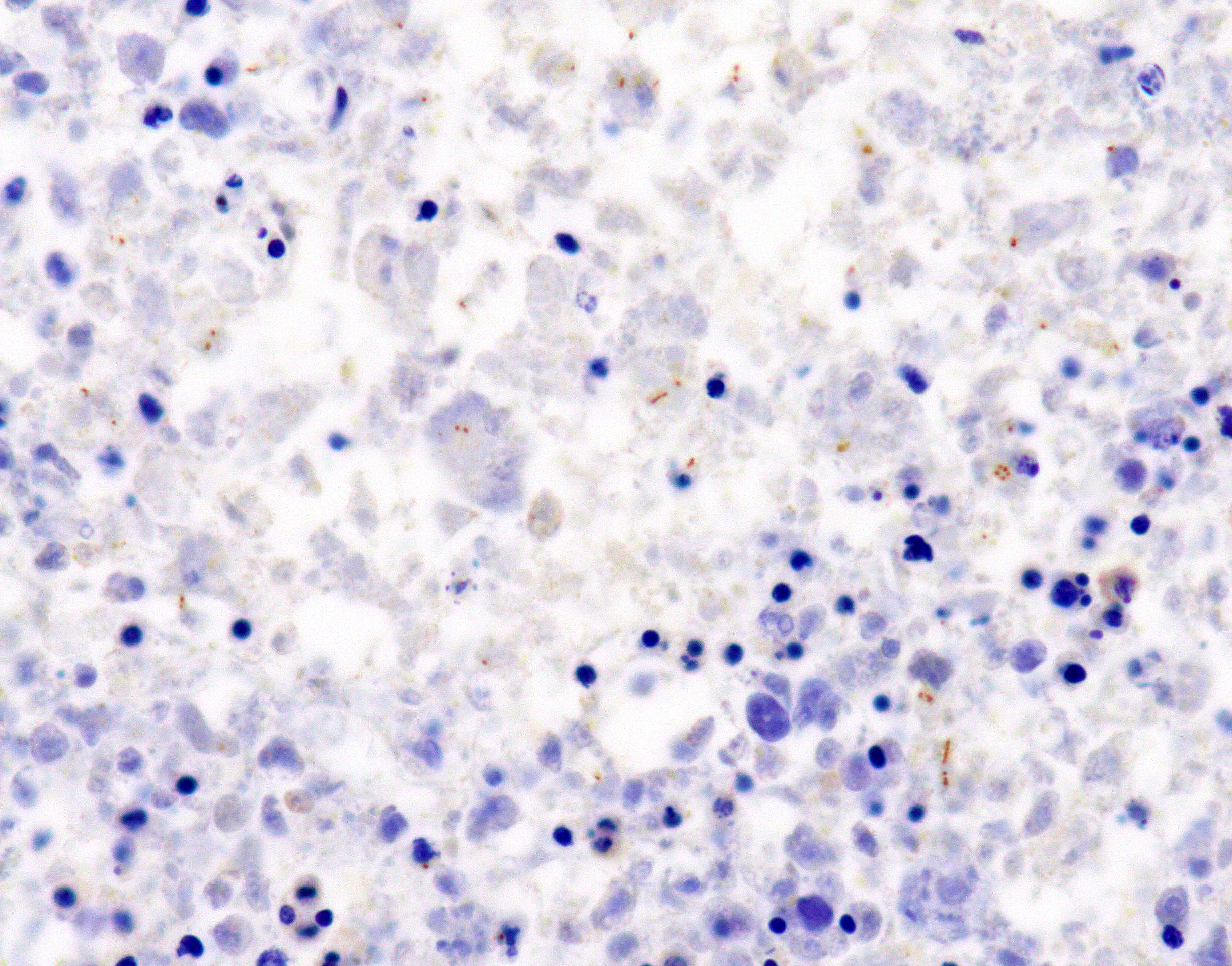

Microscopic description:

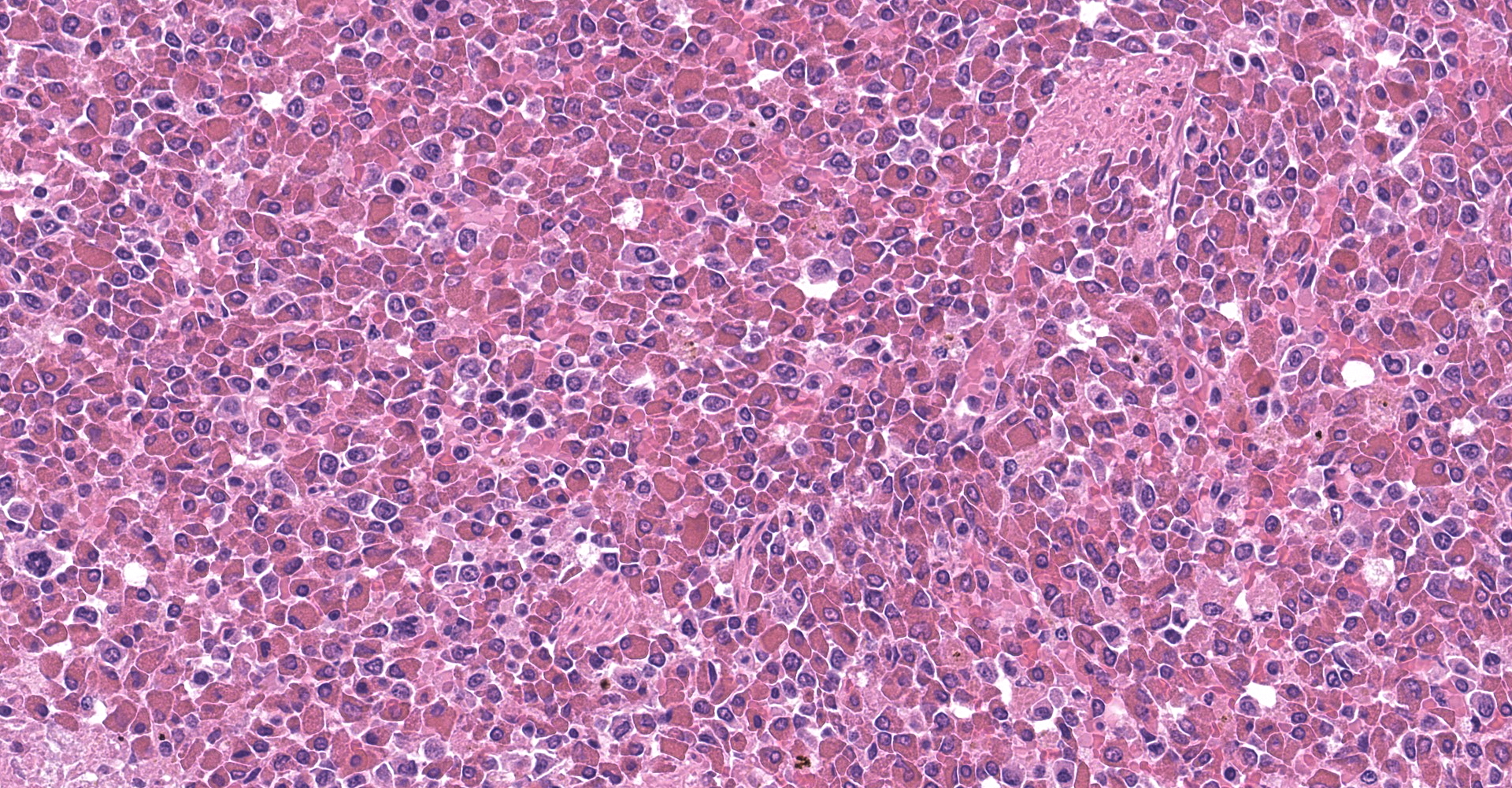

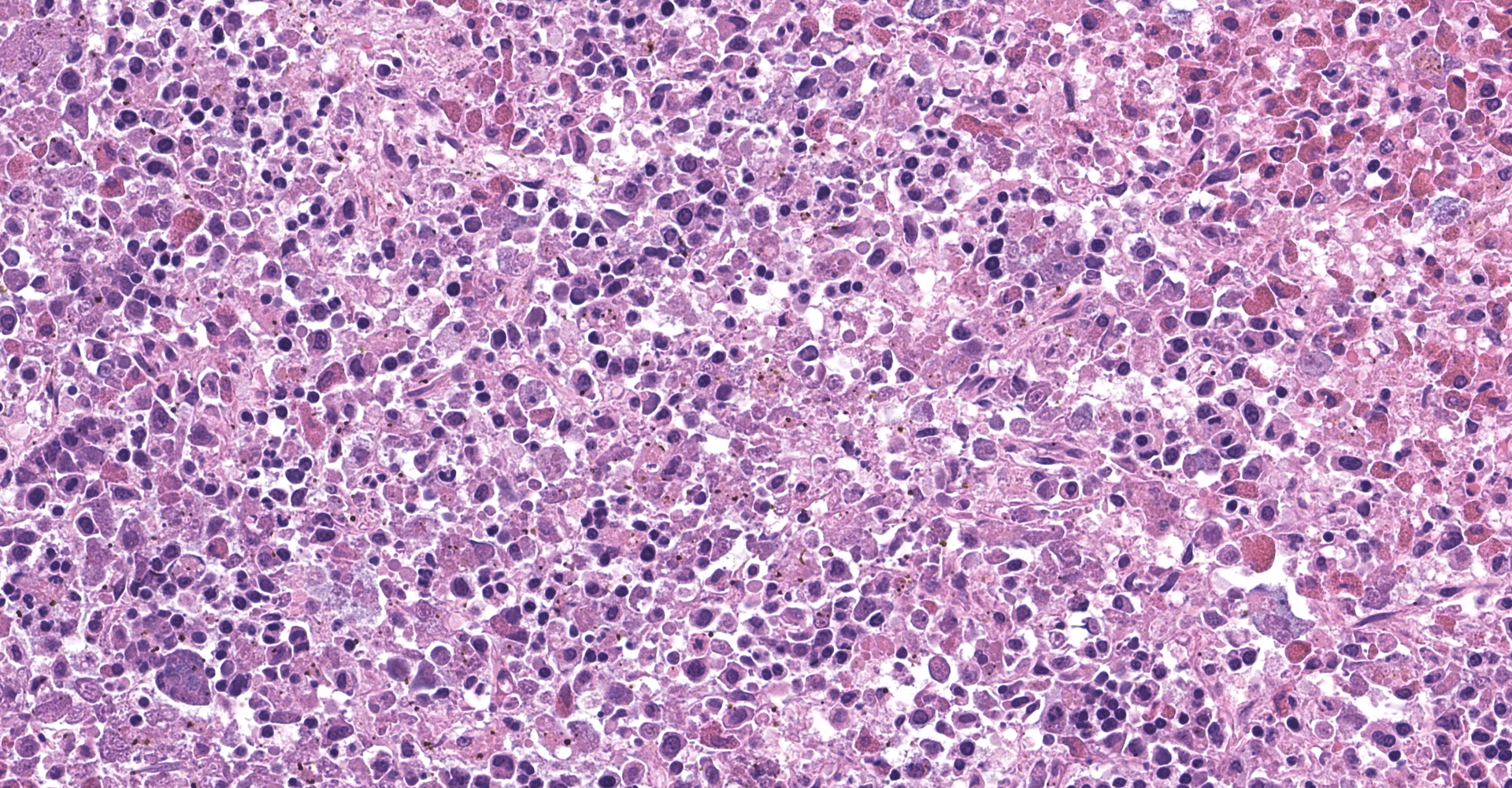

Spleen: The splenic parenchyma was effaced by diffusely infiltrated round cells and multifocal-to-coalescing necrotizing granulomatous lesions infiltrated with macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils. The infiltrated round cells were of intermediate size with distinct cell borders and had moderate amount of cytoplasm composed of abundant eosinophilic granules. The eosinophils had round, hyperchromatic nuclei with diameters ranging from 4 to 6 microns, and sometimes showed reniform or two-lobed nuclei. Mitotic figures were rare. Eosinophils infiltrated the splenic trabeculae and around trabecular arteries, and partially, in the extracapsular region. Rarely, poorly stained bacilli were observed within macrophages and necrotizing area in the granulomatous lesion. Erythroid and myeloid precursors and megakaryocytes were diffusely scattered (extramedullary hematopoiesis).

Lung, liver, left inguinal lymph node, and distal end of left hindlimb (not submitted): Eosinophil infiltration observed around the vessels and granulomatous lesions of the spleen were similarly observed in the lung, liver, left inguinal lymph node, and distal end of the left hindlimb.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

1. Spleen: Eosinophilic leukemia.

2. Spleen: Splenitis, necrotizing granulomatous, multifocal to coalescing, with intracellular and extracellular bacilli.

3. Spleen: extramedullary hematopoiesis.

Contributor's comment:

Histopathologic lesions in the spleen showed eosinophilic leukemia and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, suggesting involvement of a pathogen. Mycobacterium marinum was confirmed by PCR, Ziehl-Neelsen stain, and immunohistochemistry.

Eosinophilic leukemia (chronic eosinophilic leukemia), also called myeloproliferative neoplasia, is a subtype of chronic myeloid leukemia that is rare in animals.3 In four-toed hedgehogs, five cases of eosinophilic leukemia have previously been reported.4,6,8 Eosinophilic leukemia needs to be differentiated from hypereosinophilic syndrome, as both conditions are characterized by eosinophil infiltration of bone marrow and systemic organs. Eosinophilic leukemia is distinct from hypereosinophilic syndrome in that the eosinophils show a more immature morphology and that there are no factors that increase eosinophils, such as allergic diseases and parasitic infections.13 Although the bone marrow could not be examined because a cosmetic necropsy was performed, a diagnosis of eosinophilic leukemia was made as the eosinophilic nuclei were round to uniform in shape, which suggest immature morphology.

Mycobacterium marinum is a causative agent of mycobacteriosis in freshwater and saltwater fishes.5 This pathogen often causes skin infections via traumatic injuries in humans through contaminated fish and fish tank. Therefore, many human patients are found to be aquarium fish owners, pet shop workers, aquarium workers, and workers in the fish market.5,11 Generally, M. marinum acts as an opportunistic pathogen, and causes localized skin lesions called 'fish tank granuloma' in most human patients.5 However, immunocompromised or immunosuppressed patients often develop more severe lesions that may progress to disseminated infection.5 M. marinum is ubiquitous in the aquatic environment and is often isolated from reptiles and amphibians, and sometimes causes disease in these animals.7,14 In mammals except humans, nontuberculous mycobacteriosis caused by M. marinum has only been reported in the European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus).12

This was a case of systemic infection caused by M. marinum. It is thought that the acid-fast bacilli infected the left hindlimb first, then spread to systemic organs. The four-toed hedgehog was kept in the household as a pet, but the source of infection is unknown. It is possible that the infection worsened due to a reduction in systemic immunity caused by eosinophilic leukemia.

Contributing Institution:

Laboratory of Pathology

Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Setsunan University

45-1 Nagaotohge-cho

Hirakata, Osaka 573-0101, Japan

JPC diagnosis:

1. Spleen: Eosinophilic leukemia (chloroleukemia).

2. Spleen: Splenitis, granulomatous, multifocal, to coalescing, with intrahistiocytic bacilli.

JPC comment:

The contributor summarized this case in an article published in 2020. While considered a rare disease in domestic animals, eight cases have previously been reported prior to this case, suggesting that these species may have a predisposition to this disease. While not available in this case, evaluation of bone marrow would provide more clinical data to definitively classify this case.9

The World Health Organization (WHO) currently defines chronic eosinophilic leukemia - not otherwise specified (CEL-NOS) a clonal expansion of eosinophils, with > 1.5 x 109/L absolute eosinophils in peripheral blood accompanied by either the presence of myeloblast excess (>2% in peripheral blood or 5-19% in bone marrow) or the presence of a clonal cytogenetic abnormality.2 The CEL-NOS excludes a variety of chronic eosinophilic leukemias that are attributed to known mutations, such as rearrangement of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, or FGFR1, or PCM1-JAK2, ETV6-JAK2, or BCR-JAK2 fusion.1

Recent investigation of a human case of chronic eosinophilic leukemia revealed no mutations in PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, and several other known myeloproliferative mutations. However, using next-generation sequencing, this patient's leukemia was characterized by an insertion/deletion mutation in exon 13 of JAK2 (JAK2ex13InDel).10 While this mutation is not the basis of every case of human chronic eosinophilic leukemia, and veterinary species may have a different basis of pathogenesis, additional research may reveal a common mutation that could be targeted with therapeutics to improve outcomes.

References:

1. Bain BJ, Horny HP, Hasserjian RP, Orazi A. Chronic eosinophilic leukaemia, NOS. In: WHO classification of tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid tissues. Herndon, VA: Stylus Publishing, LLC. 2017:71-79.

2. Barbui T, Thiele J, Gisslinger H, et al. The 2016 WHO classification and diagnostic criteria for myeloproliferative neoplasms: document summary and in-depth discussion. Blood Cancer Journal. 2018;8:15.

3. Boes KM, Durham AC. Chronic myeloid leukemia. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017:755.

4. Escobar-Alarcón DK, Reyes-Matute A, Méndez-Bernal A, et al. Chronic eosinophilic leukemia in an African hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Braz J Vet Pathol. 2016;9:34-38.

5. Hashish E, Merwad A, Elgaml S, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection in fish and man: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management; a review. Vet Q. 2018;38:35-46.

6. Higbie CT, Eshar D, Choudhary S, et al. Eosinophilic leukemia in a pet African hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). J Exot Pet Med. 2016;25:65-71.

7. Jacobson ER. Mycobacterium. In: Jacobson ER, ed. Infectious Diseases and Pathology of Reptiles. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007:468-469.

8. Martínez-Jiménez D, Garner B, Coutermarsh-Ott S, et al. Eosinophilic leukemia in three African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris) and validation of Luna stain. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2017;29:217-223.

9. Nakamura S, Yasuda M, Ozaki K, Tsukahara T. Eosinophilic leukaemia and systemic Mycobacterium marinum infection in an African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). J Comp Path. 2020;181:33-37.

10. Patel AB, Franzini A, Leroy E, et al. JAK2ex13InDel drives oncogenic transformation and is associated with chronic eosinophilic leukemia and polycythemia vera. Blood. 2019;134(26):2388-2398.

11. Sia TY, Taimur S, Blau DM, et al. Clinical and pathological evaluation of Mycobacterium marinum group skin infections associated with fish markets in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:590-595.

12. Tappe JP, Weitzman I, Liu S, et al. Systemic Mycobacterium marinum infection in a European hedgehog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;183:1280-1281.

13. Valli VE. Chronic eosinophilic leukemia and hypereosinophilic syndrome. In: Valli VE, ed. Veterinary Comparative Hematopathology. Ames, IA: Blackwell publishing; 2007:436-440.

14. Whitaker BR, Wright KM. Bacterial diseases. In: Divers SJ and Stahl SJ, eds. Mader's Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2019:1001-1003.