Signalment:

Gross Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

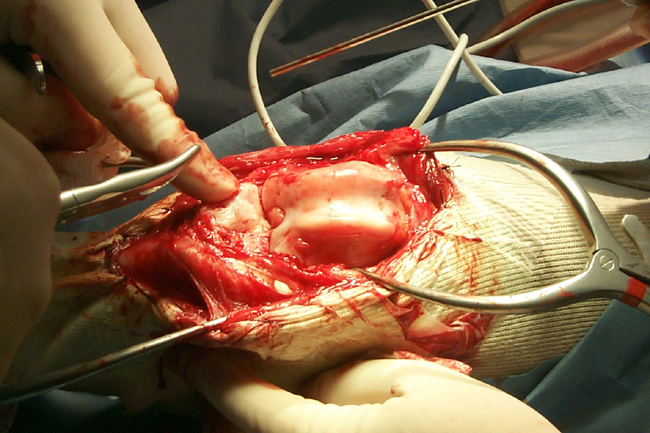

Synovial osteochondromatosis, or synovial chondrometaplasia, is a proliferative disorder of undifferentiated stem cells of the synovium. The proposed pathogenesis is the transformation of fibroblast-like cells under the influence of extracellular chondroid matrix material into chrondroblastic cells. It is these transformed cells that are believed to give rise to the characteristic cartilaginous nodules. These nodules may grow and project out form the synovium on delicate vascular pedicles, or as seen in this case, may form a more broad-based nodular mass. When their base is narrow, they often break off and form loose bodies within the joint. The chondrocytes of the loose body are nourished by the synovial fluid and thus will continue to form more cartilage matrix and increase in size. This will often result in degenerative joint disease due to physical damage to the adjacent joint capsule and articular cartilage. If the nodules remain attached to the synovium (as was seen in this case) they will often undergo endochondral ossification with the formation of broad trabeculae of bone. In dogs, the disease is usually seen in medium to large breeds, and has been described int eh scapulohumeral, coxofemoral, talocrural, and stifle joints. There is usually no history of trauma or primary degenerative joint disease (such as osteochondritis dissecans).

In humans, osteochondromatosis is uncommon and most often occurs in the stifle joint of middle aged males. The condition in humans has been classified into primary and secondary forms. The primary form is described as the spontaneous formation of intrasynovial nodules in an otherwise normal joint. It is usuallyconfined to one joint, most commonly a larger joint (e.g. knee, hip, shoulder, elbow, and ankle). Histologically, the primary form has been described as foci of chondrometaplasia that contain chondrocytes with cellular atypia. The recurrence rate with this form is considered high. Secondary synovial osteochondromatosis is a similar condition that follows traumatic, degenerative, or inflammatory joint diseases. In this condition, detached fragments of cartilage or subchondral bone become implanted within the synovium and incite the formation of chondrometaplastic nodules. With the secondary form, there is little to no cytological atypia, and the condition usually responds favorably to surgical intervention, provided that the initial joint disease is not allowed to progress.

In the past, an attempt has been made to apply the above-mentioned classification to canine patients with osteochondromatosis, but this has proven to be difficult, as many lesions in the dog do not fit all the criteria of either classification. In the present case, there was no appreciable cellular atypia seen and there was evidence of degenerative joint disease. This would be most consistent with a classification of secondary osteochondromatosis. However, the patient had no history of trauma, and the lesion was confined to one stifle joint. This is more typical of the primary form. A lack of cellular atypia argues for the secondary form, but cellular atypia may not be seen in all primary cases. The presence of degenerative joint disease is not in of itself an adequate criterion for the secondary form, as the formation of osteochondromatous nodules can lead to degenerative changes within the adjacent synovium. Regardless of the classification scheme used, the prognosis for dogs with this condition appears to depend on the degree of degenerative joint disease noted at the time of surgery, as well as the ability to perform total synovectomy with removal of any loose bodies. Recurrence with incomplete removal of the affected synovium and/or loose bodes has been reported. Complete synovectomy may be impossible, however, and temporary relief has been reported with loose body removal alone. The dog in this report was doing well (no lameness reported) 2 months post-surgery.

Differential diagnosis should include severe degenerative joint disease, osteochondral fractures secondary to trauma, osteochondritis dissecans, and neoplasi, particularly chondrosarcoma.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Osteochondral metaplasia can occur within any synovial lined structure, such as a joint, tendon sheath, or bursa.4 Ectopic ossification of these structures requires a vascular supply, and the presence of detached osseous bodies (joint mice) implies a previous attachment to the synovial surface.

The underlying cause of osteochondral metaplasia in animals is not known. Due to the relatively limited responses of the joint, it can often be difficult to distinguish osteochondral metaplasia from other disease processes that result in intra-articular joint bodies such as osteochondrosis or chip fractures.4

There is some variability in the slides. Most slides exhibit lamellar bone formation, and only a few slides exhibiting both lamellar and chondroid bone formation. Lamellar bone is formed by endochondral ossification with a sharp line of demarcation between cartilage and bone.5 Chondroid bone is formed directly from fibrocartilage, with blending of the cartilage and bone.Â

References:

2. Flo GL, Stickle RL, Dunstan RW. Synovial chondrometaplasia in five dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987 Dec 1;191(11):1417-22.

3. Gregory SP, Pearson GR. Synovial osteochondromatosis in a Labrador retriever bitch. J Small Anim Pract 1990 Nov; 31[11]:580-583.

4. Newell SM, Roberts RE, Baskett A. Presumptive tenosynovial osteochondromatosis in a horse. Vet Radiol 1996 Jan/Feb; 37[1]:112-115.

5. Thompson K: Bones and joints. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 136-145. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007