Signalment:

Gross Description:

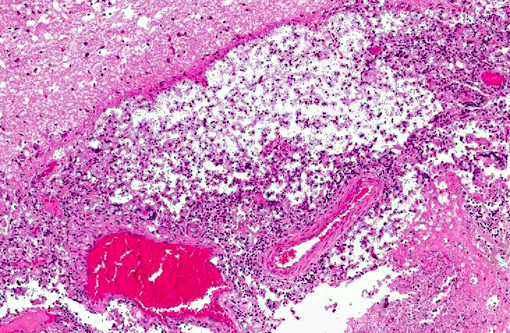

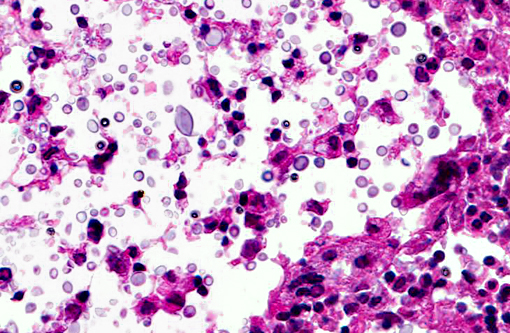

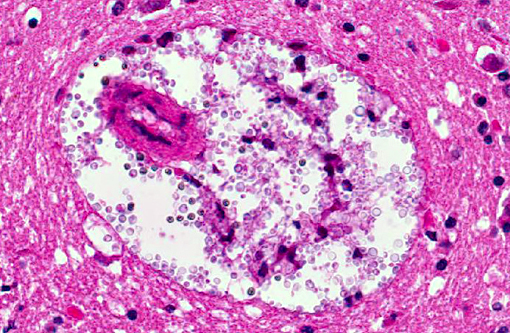

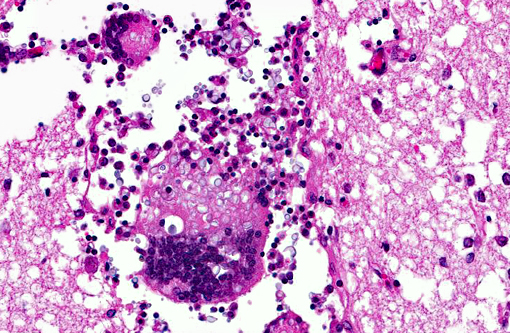

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In our case, the PCR resulted as Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii.Â

Cryptococcosis is the most common systemic mycotic disease of cats worldwide, but has been described in other domestic species (ferrets, horses, cattle, goats, sheep and llamas) and non-domestic species (parrots, elk, koalas and dolphins).(1,7) The disease is sporadic and the infection is neither contagious nor zoonotic.(1) To our knowledge, Cryptococcus has not been described in hedgehogs. This animal was kept in an open wildlife park environment. The immune status was unknown. Similar lesions containing yeasts were also found in the lung and kidney, the infection was considered as systemic. Clinical presentations of cryptococcosis are similar in all described animals; althought C. gattii appears to be more virulent and has a greater propensity to infect the CNS.(7) The route of entry is considered by inhalation of basidiospores (yeast cells).(1) CNS penetration is a consequence of the number of organisms inhaled, the virulence of the isolate and the ease of penetration of the nasal and frontal bones and the cribiform plate.(7) It is described that dogs, in comparison to cats, develop a marked inflammatory response, primarily mixed cellular or granulomatous, whereas cats develop a mild, primarily neutrophilic response.(9) In the present case of the hedgehog, there is a moderate to severe granulomatous meningoencephalitis, similar to the described lesions in dogs. Reports of cerebral cryptococcosis without respiratory involvement in domestic animals are scarce, though described in cats(6), horses(2) and in cows.(5)

Recent reports of CNS cryptococcosis include single reports in a bull from Brazil(8) and smaller series of animals as in dogs and cats from California.(9) A special variant of CNS cryptococcosis is the so called cryptococcoma, a single gelatinous pseudocyst in the CNS, often suggested as neoplasia with MRI.(9) The cyst is histologically composed of cryptococcal organisms surrounded by a pyogranulomatous inflammatory reaction and necrosis.(5,6) In people, neurocryptococcosis is linked to immunosuppression, often seen in HIV-infected patients. Whether the same is true in animals remains the subject of debate.(6)

Here, diagnosis was based on H&E histology, supported by special stains and a PCR investigation: The wall of the yeasts stained positive with Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and Grocott and the capsule stained positive with Mayers mucicarmine. PCR: Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii.Â

Histological differential diagnoses based on similar morphology: Blastomyces dermatitidis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Candida albicans, Sporothrix schenkii and Prototheca spp.(5)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The thick polysaccharide capsule gives lesions a gross gelatinous appearance, and in the cerebrum these often characteristically develop into cystic spaces as mentioned by the contributor. This is most commonly observed in cats and occurs through a repetitive process of macrophage phagocytosis, cell lysis and subsequent chemotaxis of additional macrophages allowing an expansive accumulation of the polysaccharide capsule.(10) The pathogenesis of this infection is curious, and largely still unexplained as to why the variability in inflammatory responses and lesion development occurs. Findings such as large cryptococcomas being more commonly reported in immunocompetent patients(9), and the lack of increased susceptibility in cats with retrovirus infections(7) seem to be counterintuitive. Overall, cryptococcosis is a disease often associated with a poor prognosis, as median survival time (MST) for all cats was just 19 days in one study despite treatment with antifungal drugs.(9) But when excluding the rapidly deteriorating patients, or those which didnt survive the first three days following diagnosis, the MST is much longer with many cats surviving past the conclusion of the study.(9)

The presentation of Cryptococcus in a hedgehog is unique, and conference participants discussed other known diseases within this species as they are becoming increasingly popular as pets. Hedgehogs seem to have a high incidence of neoplasia, with its prevalence at necropsy being as high as 53%.(4) Another condition first described in the mid-1990s is a progressive paralysis called Wobbly hedgehog syndrome with an incidence of 10% in pet hedgehogs in North America.(4) This is characterized histologically as vacuolation of the white matter tracts without an inflammatory infiltrate,(4) similar to degenerative myelopathy which occurs commonly in German Shepherd Dogs.

References:

1. Caswell JL, Williams KJ. The respiratory system In: Maxie, MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2007:642-644.Â

2. Cho DY, Pace LW, Beadle RE. Cerebral crytococcosis in a horse. Vet Pathol. 1986;23:207-209.Â

3. Fragnello J, Dutra V, Schrank A, et al. Identification of genomic differences between Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by representational differences analysis (RDA). Med Mycol. 2009;47:584-591.Â

4. Gibson CJ, Parry NA, Jakowski RM, Eshar D. Anaplastic astrocytoma in the spinal cord of an African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Vet Pathol. 2008;45:934-938.

5. Magalhaes GM, Elsen Saut JP, Beninati T, et al. Cerebral cryptococcomas in a cow. J Comp Path. 2012;147:106-110.Â

6. Mandrioli L, Bettini G, Marcato, OS, et al. Central nervous system Cryptococcoma in a cat. J Vet Med A. 2002;49:526-530.Â

7. Lester SJ, Malik R, Bartlett KH, et al. Cryptococcosis: update and emergence of Cryptococcus gattii. Vet Clin Pathol. 2011;40:4-17.Â

8. Riet-Correa F, Krockenberger M, Dantas AFM, et al. Bovine cryptococcal meningoencephalitis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2011;23:1056-1060.Â

9. Sykes JE, Sturges BK, Cannon MS, et al. Clinical signs, imagin features, neuropathology, and outcome in cats and dogs with central nervous system cryptococcosis from California. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1427-1438.Â

10. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds.Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. v5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:237.